Chapter 1 Introduction to the Geology of Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS

Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Table of Contents Foreword 3 About this report 5 Highlights in Achievements 7 Progress and Achievements 9 ....... Access to services to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV improved 9 ....... Access to services to prevent transmission of HIV in injecting drug use ....... improved 18 ....... Knowledge and attitudes improved 27 ....... Access to services for HIV care and support improved 30 Fund Management 41 ....... Programmatic and Financial Monitoring 41 ....... Financial Status and Utilisation of Funds 43 Operating Environment 44 Annexe 1: Implementing Partners expenditure and budgets 45 Annexe 2: Summary of Technical Progress Apr 2004–Mar 2007 49 Annexe 3: Achievements by Implementing Partners Round II, II(b) 50 Annexe 4: Guiding principles for the provision of humanitarian assistance 57 Acronyms and abbreviations 58 1 Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS 2 Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Foreword This report will be the last for the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar (FHAM), covering its fourth and final year of operation (the fiscal year from April 2006 through March 2007). Created as a pooled funding mechanism in 2003 to support the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS in Myanmar, the FHAM has demonstrated that international resources can be used to finance HIV services for people in need in an accountable and transparent manner. As this report details, progress has been made in nearly every area of HIV prevention – especially among the most at-risk groups related to sex work and drug use – and in terms of care and support, including anti-retroviral treatment. -

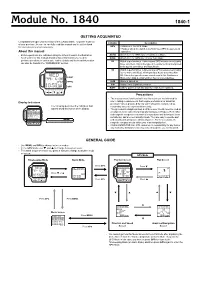

Module No. 1840 1840-1

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy 2014

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy Revised Version 2014.1 Snow Leopard Network 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Snow Leopard Network concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright: © 2014 Snow Leopard Network, 4649 Sunnyside Ave. N. Suite 325, Seattle, WA 98103. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Snow Leopard Network (2014). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy. Revised 2014 Version Snow Leopard Network, Seattle, Washington, USA. Website: http://www.snowleopardnetwork.org/ The Snow Leopard Network is a worldwide organization dedicated to facilitating the exchange of information between individuals around the world for the purpose of snow leopard conservation. Our membership includes leading snow leopard experts in the public, private, and non-profit sectors. The main goal of this organization is to implement the Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (SLSS) which offers a comprehensive analysis of the issues facing snow leopard conservation today. Cover photo: Camera-trapped snow leopard. © Snow Leopard -

Moüjmtaiim Operations

L f\f¿ áfó b^i,. ‘<& t¿ ytn) ¿L0d àw 1 /1 ^ / / /This publication contains copyright material. *FM 90-6 FieW Manual HEADQUARTERS No We DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 30 June 1980 MOÜJMTAIIM OPERATIONS PREFACE he purpose of this rUanual is to describe how US Army forces fight in mountain regions. Conditions will be encountered in mountains that have a significant effect on. military operations. Mountain operations require, among other things^ special equipment, special training and acclimatization, and a high decree of self-discipline if operations are to succeed. Mountains of military significance are generally characterized by rugged compartmented terrain witn\steep slopes and few natural or manmade lines of communication. Weather in these mountains is seasonal and reaches across the entireSspectrum from extreme cold, with ice and snow in most regions during me winter, to extreme heat in some regions during the summer. AlthoughNthese extremes of weather are important planning considerations, the variability of weather over a short period of time—and from locality to locahty within the confines of a small area—also significantly influences tactical operations. Historically, the focal point of mountain operations has been the battle to control the heights. Changes in weaponry and equipment have not altered this fact. In all but the most extreme conditions of terrain and weather, infantry, with its light equipment and mobility, remains the basic maneuver force in the mountains. With proper equipment and training, it is ideally suited for fighting the close-in battfe commonly associated with mountain warfare. Mechanized infantry can\also enter the mountain battle, but it must be prepared to dismount and conduct operations on foot. -

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Us Department of the Treasury

2/12/2021 United States Targets Leaders of Burma’s Military Coup Under New Executive Order | U.S. Department of the Treasury U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY United States Targets Leaders of Burma’s Military Coup Under New Executive Order February 11, 2021 Washington – Today, the Biden administration launched a new sanctions regime in response to the Burmese military’s coup against the democratically elected civilian government of Burma. In coordination with the issuance of a new Executive Order (E.O.), the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated, pursuant to that E.O., 10 individuals and three entities connected to the military apparatus responsible for the coup. The United States will continue to work with partners throughout the region and the world to support the restoration of democracy and the rule of law in Burma, to press for the immediate release of political prisoners, including State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, and to hold accountable those responsible for attempting to reverse Burma’s progress toward democracy. These sanctions specifically target those who played a leading role in the overthrow of Burma’s democratically elected government. The sanctions are not directed at the people of Burma. “As the President has said, the February 1 coup was a direct assault on Burma’s transition to democracy and the rule of law,” said Secretary Janet L. Yellen. “The Treasury Department stands with the people of Burma — and we are doing what we must to help them in their eort to secure freedom and democracy.” “We are also prepared to take additional action should Burma’s military not change course. -

Translated from the Hmannan Yazawin Dawgyl

Burmese I11vasions of Siam, Translated from the Hmannan Yazawin DawgyL ...T . Preface. 'l' he materials for the subject of this paper ·were ch awn almost entirely from the Hmn.nn a 11 Yazawin Dclwg·yi, a H istory of Burm a. in Burmese co1npil eLl by order of King Dagyict <l W of Burma i11 the ycn.r 1 101 B unnese era., A. D . 182!J . The nn t.ive work lms be en closely ac1l1erec1 to in tl1i · pnper, so nmch so that it may he co nsidered a free translat ion ( lr the original coveri 11g t he ~_J e r i o d treated of. A resume of the whole of '\vhat i · containea h re IYill lJe found in Sir A. rtlnu Phayre's llislory of Bul'lna . J n hi s l1 ist ory Sir Art hur Phayre has <Li so f ollowetl t lJ e Hmanua n Yazawin L irly closely, a nd he has utilized a1l th e in fonnat.ion IYh i.ch tl~e 1mt. ire work can offer t hat is worthy of a place in a history w rit t<~ n on European lines aml an::mgo cl it, at least tLS regards the p t·e-Alaungpric period, alm ost in the ordet· it is give n in the orig· in al. But what a, wide difference t here is between history written according to nnti ve ideas and that wr itten ou E nropoa.n principles, a. nd how far Si r Ar thur Phayre has sifted nud coudensed tl1e infon nat.ion co ntained in the original may be imagined when fi fteen pages, each containi ng t wenty eigltt lines of print in the nati1 e hist ory are wo rl.: ed into thirty one lines in Sir Arthur P ha:r re'::; . -

Report on the Ecotourism Assessment of Popa Mountain Park

Report on the ecotourism assessment of Popa Mountain Park Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division & Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association October 2017 Report on the ecotourism assessment of Popa Mountain Park Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division & Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association October 2017 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Objective .................................................................................................................................................... 1 3. Current situation and opportunity for ecotourism .................................................................................... 1 3.1 Road communication ............................................................................................................................... 2 3.2 Opportunity for recreation ..................................................................................................................... 2 3.3 Opportunity for research ......................................................................................................................... 2 3.3.1 Hiking in the forest ........................................................................................................................... 2 3.3.2 Mountaineering and camping ............................................................................................................ 2 3.4 Opportunity -

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: to Be a Modern Burmese Citizen Living in a Nation‐State, 1889 – 1962

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: To be a modern Burmese citizen living in a nation‐state, 1889 – 1962 Yuri Takahashi Southeast Asian Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney April 2017 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Yuri Takahashi 2 April 2017 CONTENTS page Acknowledgements i Notes vi Abstract vii Figures ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Biography Writing as History and Shwe U Daung 20 Chapter 2 A Family after the Fall of Mandalay: Shwe U Daung’s Childhood and School Life 44 Chapter 3 Education, Occupation and Marriage 67 Chapter ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1917 and 1930 88 Chapter 5 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1930 and 1945 114 Chapter 6 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1945 and 1962 140 Conclusion 166 Appendix 1 A biography of Shwe U Daung 172 Appendix 2 Translation of Pyone Cho’s Buddhist songs 175 Bibliography 193 i ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I came across Shwe U Daung’s name quite a long time ago in a class on the history of Burmese literature at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. -

(BRI) in Myanmar

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 22 | November 2019 Selling the Silk Road Spirit: China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Myanmar Key points • Rather than a ‘grand strategy’ the BRI is a broad and loosely governed framework of activities seeking to address a crisis in Chinese capitalism. Almost any activity, implemented by any actor in any place can be included under the BRI framework and branded as a ‘BRI project’. This allows Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and provincial governments to promote their own projects in pursuit of profit and economic growth. Where necessary, the central Chinese government plays a strong politically support- ive role. It also maintains a semblance of control and leadership over the initiative as a whole. But with such a broad framework, and a multitude of actors involved, the Chinese government has struggled to effectively govern BRI activities. • The BRI is the latest initiative in three decades of efforts to promote Chinese trade and investment in Myanmar. Following the suspension of the Myitsone hydropower dam project and Myanmar’s political and economic transition to a new system of quasi-civilian government in the early 2010s, Chinese companies faced greater competition in bidding for projects and the Chinese Government became frustrated. The rift between the Myanmar government and the international community following the Rohingya crisis in Rakhine State provided the Chinese government with an opportunity to rebuild closer ties with their counterparts in Myanmar. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) was launched as the primary mechanism for BRI activities in Myanmar, as part of the Chinese government’s economic approach to addressing the conflicts in Myanmar. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

December 2008

cover_asia_report_2008_2:cover_asia_report_2007_2.qxd 28/11/2008 17:18 Page 1 Central Committee for Drug Lao National Commission for Drug Office of the Narcotics Abuse Control Control and Supervision Control Board Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, A-1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43 1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43 1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand OPIUM POPPY CULTIVATION IN SOUTH EAST ASIA IN SOUTH EAST CULTIVATION OPIUM POPPY December 2008 Printed in Slovakia UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems in the context of the illicit crop elimination objective set by the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs. ICMP provides overall coordination as well as direct technical support and supervision to UNODC supported illicit crop surveys at the country level. The implementation of UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in South East Asia was made possible thanks to financial contributions from the Government of Japan and from the United States. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop-monitoring/index.html The boundaries, names and designations used in all maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document has not been formally edited. CONTENTS PART 1 REGIONAL OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................3