Nandini Sundar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Lunglei District

DISTRICT AGRICULTURE OFFICE LUNGLEI DISTRICT LUNGLEI 1. WEATHER CONDITION DISTRICT WISE RAINFALL ( IN MM) FOR THE YEAR 2010 NAME OF DISTRICT : LUNGLEI Sl.No Month 2010 ( in mm) Remarks 1 January - 2 February 0.10 3 March 81.66 4 April 80.90 5 May 271.50 6 June 509.85 7 July 443.50 8 August 552.25 9 September 516.70 10 October 375.50 11 November 0.50 12 December 67.33 Total 2899.79 2. CROP SITUATION FOR 3rd QUARTER KHARIF ASSESMENT Sl.No . Name of crops Year 2010-2011 Remarks Area(in Ha) Production(in MT) 1 CEREALS a) Paddy Jhum 4646 684716 b) Paddy WRC 472 761.5 Total : 5018 7609.1 2 MAIZE 1693 2871.5 3 TOPIOCA 38.5 519.1 4 PULSES a) Rice Bean 232 191.7 b) Arhar 19.2 21.3 c) Cowpea 222.9 455.3 d) F.Bean 10.8 13.9 Total : 485 682.2 5 OIL SEEDS a) Soyabean 238.5 228.1 b) Sesamum 296.8 143.5 c) Rape Mustard 50.3 31.5 Total : 585.6 403.1 6 COTTON 15 8.1 7 TOBACCO 54.2 41.1 8 SUGARCANE 77 242 9 POTATO 16.5 65 Total of Kharif 7982.8 14641.2 RABI PROSPECTS Sl.No. Name of crops Area covered Production Remarks in Ha expected(in MT) 1 PADDY a) Early 35 70 b) Late 31 62 Total : 66 132 2 MAIZE 64 148 3 PULSES a) Field Pea 41 47 b) Cowpea 192 532 4 OILSEEDS a) Mustard M-27 20 0.5 Total of Rabi 383 864 Grand Total of Kharif & Rabi 8365 15505.2 WATER HARVESTING STRUCTURE LAND DEVELOPMENT (WRC) HILL TERRACING PIGGERY POULTRY HORTICULTURE PLANTATION 3. -

Champhai District, Mizoram

Technical Report Series: D No: Ground Water Information Booklet Champai District, Mizoram Central Ground Water Board North Eastern Region Ministry of Water Resources Guwahati October 2013 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET CHAMPHAI DISTRICT, MIZORAM DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. ITEMS STATISTICS No. 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical Area (sq.km.) 3,185.8 sq km ii) Administrative Divisions (as on 2011) There are four blocks, namely; khawjawl,Khawbung,Champai and Ngopa,RD Block.. iii) Population (as per 2011 Census) 10,8,392 iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 2,794mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY i) Major Physiographic Units Denudo Structural Hills with low and moderate ridges. ii) Major Drainages Thhipui Rivers 3. LAND USE (sq. km.) More than 50% area is covered by dense forest and the rest by open forest. Both terraced cultivation and Jhum (shifting) tillage (in which tracts are cleared by burning and sown with mixed crops) are practiced. 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Colluvial soil 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS Fibreless ginger, paddy, maize, (sq.km.) mustard, sugarcane, sesame and potato are the other crops grown in this area. 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES N.A (sq.km.) Other sources Small scale irrigation projects are being developed through spring development with negligible command area. 7. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Lower Tertiary Formations of FORMATIONS Oligocene and Miocene Age 8. HYDROGEOLOGY i) Major water Bearing Formations Semi consolidated formations of Tertiary rocks. Ground water occurs in the form of spring emanating through cracks/fissures/joints etc. available in the country rock. 9. GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY CGWB (as on 31.03.09) Nil 10. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

Result 20.1.2020

No.A.12040/1/2019-ZMC Dated Falkawn, the 21st January, 2020 CIRCULAR The following candidates are recommended by the Selection and Recruitment Committee held on the 20th January, 2020 for appointment/engagement to the mentioned posts under Zoram Medical College, Falkawn as shown below: 1. Senior Resident, Department of General Surgery: Regular Basis with remuneration of Level 11 in the Pay Matrix + NPA and other permissible allowance. Sl. No. Name Address 1. Dr. Paleti Venu Gopala Reddy T-56, Saikhamakawn, Aizawl The Selection & Recruitment Committee further recommended the following candidates against the post of Senior Resident (General Surgery) to be placed in the reserved panel which shall be valid for a period of one year for filling up the same vacancies only in case candidates in the regular panel are not available for appointment on account of declination of appointment or resignation or death of the recommended candidates. Sl. No. Name Address 1. Dr. Zochampuia Ralte Luangmual Venglai, Aizawl 2. Senior Resident, Department of General Medicine: Regular Basis with remuneration of Level 11 in the Pay Matrix + NPA and other permissible allowance. Sl. No. Name Address 1. Dr. Lalthafala V/C-38, Vaivakawn, Aizawl Due to non-availability of candidates, there is no candidate recommended in the reserved panel for the post of Senior Resident in the department of General Medicine. Page 1 of 3 3. Statistician cum Tutor/Demonstrator, Department of Community Medicine: Regular Basis with remuneration of Academic Level 10 in the Pay Matrix and -

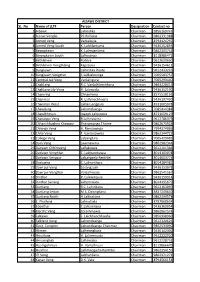

AIZAWL EAST MEDICAL OFFICER Place of Sl No Name of Trained Person Posting Place Date of Training Contact No Training 1 Dr

AIZAWL EAST MEDICAL OFFICER Place of Sl No Name of Trained Person Posting Place Date of Training Contact No Training 1 Dr. Lalparliani Darlawn 5th - 12th Nov. 2008 CHA 94361514628 2 Dr. Lalmalsawmi Khawlhring UHC Ramhlun 5th - 12th Nov. 2008 CHA 9862373437 3 Dr. Zorinsangi Khiangte Thingsulthliah 5th - 12th Nov. 2008 CHA 9436156813 4 Dr. Helen Lalnunpuii UHC ITI 5th - 12th Nov. 2008 CHA 9862540813 5 Dr. Sailopari Sailo Khawruhlian 5th - 12th Nov. 2008 CHA 9436190936 HEALTH WORKER Place of Sl No Name of Trained Person Posting Place Date of Training Contact No Training 1 Lalrokimi TNT 21st - 28th May, 2008 CHA 9862454324 2 Lalbiaksangi Sihphir 21st - 28th May, 2008 CHA 986361690 3 Vanlalhlana Bethlehem 21st - 28th May, 2008 CHA 9862331538 4 Lalbiaksangi Saitual 21st - 28th May, 2008 CHA 9862095136 5 R. Lalbialhnuni Tlungvel 21st - 28th May, 2008 CHA 9862717822 6 R. Nuzawni Khawruhlian 10th - 17th june 2008 CHA 9436196218 7 C. Zuitluanga Baktawng 10th - 17th june 2008 CHA 276126 8 M. Sangliani Khumtung 10th - 17th june 2008 CHA 9862076007 9 Rothianga Vanbawng 10th - 17th june 2008 CHA 10 Lalnunhluni Kepran 1st - 8th July 2008 CHA 9863328261 11 Lalbiakengi Darlawn 1st - 8th July 2008 CHA 12 Ramhluni Thingsulthliah 1st - 8th July 2008 CHA 9436193186 13 Lalnuntluangi Zemabawk 1st - 8th July 2008 CHA 2331018 14 Vanlalhawni Suangpuilawn 1st - 8th July 2008 CHA 0389-2900736 15 R. Lalmuankima Sakawrdai 1st - 8th July 2008 CHA 9863222336 16 PC. Lalhliri Thuampui 23rd - 30th Sept. 2008 CHA 2328608 17 Sangziki Rulchawm 23rd - 30th Sept. 2008 CHA 9863622556 18 Lalhlimpuii Colney Sawleng 23rd - 30th Sept. 2008 CHA 19 Lalrinngama Sesawng 23rd - 30th Sept. -

SL. No Name of LLTF Person Designation Contact No 1 Aibawk

AIZAWL DISTRICT SL. No Name of LLTF Person Designation Contact no 1 Aibawk Lalrindika Chairman 9856169747 2 Aizawl Venglai PC Ralliana Chairman 9862331988 3 Armed Veng Vanlalbula Chairman 8794424292 4 Armed Veng South K. Lalthlantuma Chairman 9436152893 5 Bawngkawn K. Lalmuankima Chairman 9862305744 6 Bawngkawn South Lalrosanga Chairman 8118986473 7 Bethlehem Rohlira Chairman 9612629630 8 Bethlehem Vengthlang Kapzauva Chairman 9436154611 9 Bungkawn Lalrindika Royte Chairman 9612433243 10 Bungkawn Vengthar C.Lalbiaknunga Chairman 7005583757 11 Centtral Jail Veng Vanlalngura Chairman 7005293440 12 Chaltlang R.C. Vanlalhlimchhana Chairman 9863228015 13 Chaltlang Lily Veng H. Lalenvela Chairman 9436152190 14 Chamring Chhanhima Chairman 8575518166 15 Chanmari R. Lalhmachhuana Chairman 9436197490 16 Chanmari West Lalliansangpuia Chairman 8731005978 17 Chawilung Lalnuntluanga Chairman 7085414388 18 Chawlhhmun Joseph Lalnunzira Chairman 8731059129 19 Chawnpui Veng R.Lalrinawma Chairman 9612786379 20 Chhanchhuahna Khawpui Thangmanga Thome Chairman 9862673924 21 Chhinga Veng H. Ramzawnga Chairman 7994374886 22 Chite Veng F. Vanlalsawma Chairman 9862344723 23 College Veng Lalsanglura Chairman 7005429082 24 Dam Veng Lawmawma Chairman 9862982344 25 Darlawn Chhimveng Lalfakzuala Chairman 9612201386 26 Darlawn Venghlun C. Lalchanmawia Chairman 8014103078 27 Darlawn Vengpui Lalsangzela Renthlei Chairman 8014603774 28 Darlawng C. Lalnunthara Chairman 8014184382 29 Dawrpui Veng Zosangzuali Chairman 9436153078 30 Dawrpui Vengthar Vanlalhruaia Chairman 9862541567 31 Dinthar R. Lalawmpuia Chairman 9436159914 32 Dinthar Sairang Lalremruata Chairman 8014195679 33 Durtlang R.C. Lalrinliana Chairman 9612163099 34 Durtlang Leitan M.S. Dawngliana Chairman 8837209640 35 Durtlang North H.Lalthakima Chairman 9862399578 36 E. Phaileng Lalruatzela Chairman 8787868634 37 Edenthar C.Lalramliana Chairman 9436360954 38 Electric Veng Zorammawia Chairman 9862867574 39 Falkawn F. Lalchhanchhuaha Chairman 9856998960 40 Falkland Veng Lalnuntluanga Chairman 9612320626 41 Govt. -

Displaced Brus from Mizoram in Tripura: Time for Resolution

Displaced Brus from Mizoramin Tripura: Time for Resolution Brig SK Sharma Page 2 of 22 About The Author . Brigadier Sushil Kumar Sharma, YSM, PhD, commanded a Brigade in Manipur and served as the Deputy General Officer Commanding of a Mountain Division in Assam. He has served in two United Nation Mission assignments, besides attending two security related courses in the USA and Russia. He earned his Ph.D based on for his deep study on the North-East India. He is presently posted as Deputy Inspector General of Police, Central Reserve Police Force in Manipur. http://www.vifindia.org ©Vivekananda International Foundation Page 3 of 22 Displaced Brus from Mizoram in Tripura: Time for Resolution Abstract History has been witness to the conflict-induced internal displacement of people in different states of Northeast India from time to time. While the issues of such displacement have been resolved in most of the North-eastern States, the displacement of Brus from Mizoram has remained unresolved even over past two decades. Over 35,000 Brus have been living in six makeshift relief camps in North Tripura's Kanchanpur, areas adjoining Mizoram under inhuman conditions since October 1997. They had to flee from their homes due to ethnic violence in Mizoram. Ever since, they have been confined to their relief camps living on rations doled out by the state, without proper education and health facilities. Called Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), some of the young Brus from these camps have joined militant outfits out of desperation. There have been several rounds of talks among the stakeholders without any conclusive and time-bound resolutions. -

Web Directory of Mizoram

Web Directory of Mizoram Web Directory of Mizoram List of Tables 1. Apex Bodies in Mizoram 2. Legislative Assembly and Council 3: Districts (Official Website) 4: Directorate, Divisions/ Units/ Wings 5: Union Government 6. State Departments 7: Boards / Undertakings ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology, GBPIHED Web Directory of Mizoram Table 1. Apex Bodies in Mizoram Name Web Address Raj Bhawan, Mizoram https://rajbhavan.mizoram.gov.in/ Chief Minister of Mizoram https://cmonline.mizoram.gov.in/ Official Portal of Mizoram http://mizoram.nic.in/ Government State Election Commission (SEC), https://sec.mizoram.gov.in/ Mizoram Mizoram Finance Commission http://mizofincom.nic.in/ State Information Commission (SIC), https://mic.mizoram.gov.in/page/Profile.html Mizoram Mizoram Public Service Commission https://mpsc.mizoram.gov.in/ Table 2. Legislative Assembly and Council Name Web Address Legislative Assembly (Vidhan Sabha), Mizoram http://www.mizoramassembly.in/ Table 3: Districts (Official Website) S.N. Name Web Address 1 Aizawl http://aizawl.nic.in/ 2 Champhai http://champhai.nic.in/ 3 Kolasib http://kolasib.nic.in/ 4 Lawngtlai http://lawngtlai.nic.in/ 5 Lunglei http://lunglei.nic.in/ 6 Mamit http://mamit.nic.in/ 7 Saiha http://saiha.nic.in/ 8 Serchhip http://serchhip.nic.in/ ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology, GBPIHED Web Directory of Mizoram Table 4: Directorate, Divisions/ Units/ Wings S.N. Name Web Address 1 Mizoram Remote Sensing Application Centre, Planning http://mirsac.nic.in/ Department, Mizorm 2 Office of the Deputy Commissioner, Aizawl -

Andy Higgins, BA

Andy Higgins, B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) Music, Politics and Liquid Modernity How Rock-Stars became politicians and why Politicians became Rock-Stars Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Politics and International Relations The Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion University of Lancaster September 2010 Declaration I certify that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere 1 ProQuest Number: 11003507 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003507 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract As popular music eclipsed Hollywood as the most powerful mode of seduction of Western youth, rock-stars erupted through the counter-culture as potent political figures. Following its sensational arrival, the politics of popular musical culture has however moved from the shared experience of protest movements and picket lines and to an individualised and celebrified consumerist experience. As a consequence what emerged, as a controversial and subversive phenomenon, has been de-fanged and transformed into a mechanism of establishment support. -

High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India

High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India Instituted by the Planning Commission of India PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor High Level Expert Group Reporton Universal Health Coverage for India Instituted by Planning Commission of India Submitted to the Planning Commission of India New Delhi October, 2011 PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor DEDICATION "This report is dedicated to the people of India whose health is our most precious asset and whose care ¡s our most sacred duty" PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Contents PREFACE 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 VOLUME 1 53 Chapter 1: VisionforUniversalHealthCoveragefor India. 53 Chapter2 : HealthFinancingandFinancialProtection 67 Chapter3 : AccesstoMedicines ,Vaccines &Technology 92 AnnexuretoChapterl : UniversalHealthCareSystems Worldwide: SixteeninternationalCaseStudies . 114 VOLUME 2 153 Chapter4: Human Resources for Health 153 Chapter5:Health Service Norms 189 VOLUME 3 241 Chapter6: Management and Institutional Reforms. 241 Chapter7: Community Participation and Citizen Engagement 271 Chapter 8: Social Determinants of Health . 291 Chapter 9: Gender and Health 311 PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor PROCESS OF CONSULTATIONS 318 COMPOSiTION OF HIGH LEVEL EXPERT GROUP . 335 EXPERT CONSULTATIONS & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 336 ABBREVIATIONS. 339 COMPOSiTION OF HLEG SECRETARIAT 344 PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Preface The High Level Expert Group (HLEG) on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) was constituted by the Planning Commission of India in October 2010, with the mandate of developing a framework for providing easily accessible and affordable health care to all Indians. -

Morphotectonic Study in a Part of Indo-Burmese Ranges in Eastern Mizoram, India

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (July - December 2018), pp. 81-92 Research Article Open Access Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies A Journal of Pachhunga University College ISSN: 2456-3757 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Vol. 03, No. 02 July-Dec., 2018 Journal Website: https://sjms.mizoram.gov.in Morphotectonic Study in a part of Indo-Burmese Ranges in Eastern Mizoram, India Farha Zaman1,*, Devojit Bezbaruah1, Lalhmingsangi2 & Raghupratim Rakshit1 1Dept. of Applied Geology, Dibrugarh University, Dibrugarh, Assam 2Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract Mizoram fold belt, situated in geologically complex Indo-Burmese Ranges, comprises of arcuate sedimentary belt. This NS trending mountain series is cut by a number of parallel to subparallel NNE-SSW, NE-SW, and NW-SE tectonic features like faults, deformed hill ranges etc. This research work was carried out in Champhai district of eastern Mizoram, near Indo- Myanmar border. In this study, a morphotectonic analysis has been performed to know the presence of active tectonics for the region. Morphotectonic parameters were calculated for 32 basins of 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th order basins. Tuipui River had been originated near Champhai town which is supposed to be a paleo-lake. The two major rivers Tuipui and Tayo have similar entrench meander patterns which might have been controlled by some structural features. Most of the other drainage shows rectangular, trellis, oval and circular pattern along with the unique river meanders. The eastern basins of the Tuipui river mostly shows WNW highly asymmetrical (|AF|=IV) tilted basins whereas the western basins shows SE moderately asymmetrical (|AF|=III) tilted basins. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.