Moüjmtaiim Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module No. 1840 1840-1

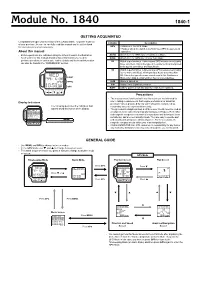

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy 2014

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy Revised Version 2014.1 Snow Leopard Network 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Snow Leopard Network concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright: © 2014 Snow Leopard Network, 4649 Sunnyside Ave. N. Suite 325, Seattle, WA 98103. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Snow Leopard Network (2014). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy. Revised 2014 Version Snow Leopard Network, Seattle, Washington, USA. Website: http://www.snowleopardnetwork.org/ The Snow Leopard Network is a worldwide organization dedicated to facilitating the exchange of information between individuals around the world for the purpose of snow leopard conservation. Our membership includes leading snow leopard experts in the public, private, and non-profit sectors. The main goal of this organization is to implement the Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (SLSS) which offers a comprehensive analysis of the issues facing snow leopard conservation today. Cover photo: Camera-trapped snow leopard. © Snow Leopard -

Plate Tectonics, Volcanoes, and Earthquakes / Edited by John P

ISBN 978-1-61530-106-5 Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor J. E. Luebering: Senior Manager Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition John P. Rafferty: Associate Editor, Earth Sciences Rosen Educational Services Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager Nicole Russo: Designer Matthew Cauli: Cover Design Introduction by Therese Shea Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plate tectonics, volcanoes, and earthquakes / edited by John P. Rafferty. p. cm.—(Dynamic Earth) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-187-4 ( eBook) 1. Plate tectonics. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Dufourspitze 4634M £1699

Icicle Mountaineering Ltd | 11a Church Street Windermere | Lake District | LA23 1AQ | UK Tel +44 (0)1539 44 22 17 | [email protected] Website: www.icicle-mountaineering.ltd.uk Online: shop.icicle-mountaineering.ltd.uk 2020 trip dossier | Dufourspitze 4634m £1699 Website link | http://www.icicle-mountaineering.ltd.uk/dufourspitze.html Key features Climb Dufourspitze, the highest mountain in Switzerland and second highest in the Alps.. 5 days guiding (Monday - Friday), with flexible itinerary to take advantage of the best conditions. Previous crampon or climbing experience is required, as this is a progression from an Intro course. Led by top qualified guides (IFMGA), guiding ratio 1:2 throughout the course. All technical equipment (e.g. B3 boots, crampons, ice axe etc.) can be hired from Icicle 2020 dates; 5 - 11 Jul, 19 - 25 Jul, 26 Jul - 1 Aug, 9 - 15 Aug, 30 Aug -+- 5 Sep. Icicle® is the registered trademark of Icicle Mountaineering UK registered company 413 6635. VAT 770 137 933 20 years ‘inspirational mountain adventure holidays’ established in 2000 Icicle Mountaineering Ltd | 11a Church Street Windermere | Lake District | LA23 1AQ | UK Tel +44 (0)1539 44 22 17 | [email protected] Website: www.icicle-mountaineering.ltd.uk Online: shop.icicle-mountaineering.ltd.uk Course overview . Climb the highest summit of Monte Rosa; Dufourspitze 4634m. It's the highest mountain in Switzerland, and the second highest in all of the Alps after Mont Blanc. We offer a week long programme to attempt this peak, as your acclimatisation and flexibility for selecting a weather window are crucial. To keep the itinerary flexibilty, the guiding ratio is 1:2 throughout, so you can take advantage of the best days for the summit weather window. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

6.Peaks in 5 Days

6 Peaksin 5 Days Not surprisingly, scaling incredible summits ranks among the most popular activities in the Alps -- including iconic peaks like the Matterhorn, the mystical Wildspitze glacier, or the vertigo-inducing Zugspitze. But if climbing isn’t your thing, you can take a cable car to the tops of these peaceful giants and enjoy the views, sans ice pick. Breathtaking view of the Zugspitze, Germany’s highest peak Germany MUNICH SALZBURG 6 BERCHTESGADEN 4 GARMISCH ZURICH Austria 5 HOHE TAUERN Switzerland 3 ÖTZTAL 2 GSTAAD 1ZERMATT 1Zermatt Picturesque Zermatt lies at the foot of the fabled Matterhorn, one of the world’s iconic mountains. The popular, car-free destination has preserved its original character and offers nearly unlimited possibilities for fun, including skiing, climbing, and hiking, as well as boutique shopping and outdoor ice-skating and curling rinks. STAY EAT DO The Omnia Mountain Lodge At Cervo Mountain Boutique Zermatt cable cars take visitors to claims pride of place on a rock Resort, Alpine-chalet design Europe’s highest mountain station high above Zermatt. merges with a hint of hunting lodge. and the Matterhorn Glacier Paradise. At the Matterhorn’s foot sits the The Cervo-Puro Restaurant boasts Gorner Gorge ranks among the most four-star superior Romantik 14 GaultMillau points. Restaurant breathtaking natural beauties of Hotel Julen, featuring 1818 serves modern Alpine cuisine. Zermatt. spruce-paneled rooms. myswitzerland.com/the-omnia-mountain-lodge myswitzerland.com/hotel-cervo.html myswitzerland.com/zermatt.htm myswitzerland.com/romantik-hotel-julen myswitzerland.com/restaurant-1818 myswitzerland.com/gorner-gorge See Amazing Blacknose Sheep Visit the legendary Blacknose Sheep in the stable of the Julen family every Wednesday. -

Chapter 4 Member States of the European Union and The

CHAPTER 4 membeR StAteS oF tHe EuroPean UnioN and tHe EuroPean EcoNomic AReA 4.1 Austria ............................................. 18 4.15 Latvia .............................................. 50 4.2 belgium ........................................... 20 4.16 lithuania ......................................... 52 4.3 Cyprus ............................................. 24 4.17 luxembourg ................................... 55 4.4 Czech Republic ............................... 26 4.18 Malta ............................................... 59 4.5 denmark ......................................... 29 4.19 Netherlands ..................................... 61 4.6 estonia ............................................. 31 4.20 Norway ............................................ 64 4.7 Finland ............................................ 33 4.21 Poland .............................................. 66 4.8 France.............................................. 35 4.22 Portugal ........................................... 69 4.9 Germany ......................................... 37 4.23 Slovakia ........................................... 71 4.10 Greece .............................................. 39 4.24 Slovenia ........................................... 74 4.11 Hungary .......................................... 41 4.25 Spain ................................................ 76 4.12 Iceland ............................................. 43 4.26 Sweden ............................................. 81 4.13 Ireland ............................................ -

Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist

STATE OF NEVADA Steve Sisolak, Governor DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Tony Wasley, Director GAME DIVISION Brian F. Wakeling, Chief Mike Cox, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Staff Specialist Pat Jackson, Predator Management Staff Specialist Cody McKee, Elk Staff Biologist Cody Schroeder, Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist Western Region Southern Region Eastern Region Regional Supervisors Mike Scott Steve Kimble Tom Donham Big Game Biologists Chris Hampson Joe Bennett Travis Allen Carl Lackey Pat Cummings Clint Garrett Kyle Neill Cooper Munson Sarah Hale Ed Partee Kari Huebner Jason Salisbury Matt Jeffress Kody Menghini Tyler Nall Scott Roberts This publication will be made available in an alternative format upon request. Nevada Department of Wildlife receives funding through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. Federal Laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability. If you believe you’ve been discriminated against in any NDOW program, activity, or facility, please write to the following: Diversity Program Manager or Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nevada Department of Wildlife 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mailstop: 7072-43 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Suite 120 Arlington, VA 22203 Reno, Nevada 8911-2237 Individuals with hearing impairments may contact the Department via telecommunications device at our Headquarters at 775-688-1500 via a text telephone (TTY) telecommunications device by first calling the State of Nevada Relay Operator at 1-800-326-6868. NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE 2018-2019 BIG GAME STATUS This program is supported by Federal financial assistance titled “Statewide Game Management” submitted to the U.S. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

Thermochronology of the Highest Central Asian Massifs (Khan Tengri -Pobedi, SE Kyrgyztan): Evidence for Late Miocene (Ca

Thermochronology of the highest Central Asian massifs (Khan Tengri -Pobedi, SE Kyrgyztan): evidence for Late Miocene (ca. 8 Ma) reactivation of Permian faults and insights into building the Tian Shan Yann Rolland, Anthony Jourdon, Carole Petit, Nicolas Bellahsen, C. Loury, Edward Sobel, Johannes Glodny To cite this version: Yann Rolland, Anthony Jourdon, Carole Petit, Nicolas Bellahsen, C. Loury, et al.. Thermochronology of the highest Central Asian massifs (Khan Tengri -Pobedi, SE Kyrgyztan): evidence for Late Miocene (ca. 8 Ma) reactivation of Permian faults and insights into building the Tian Shan. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, Elsevier, 2020, 200, pp.104466. 10.1016/j.jseaes.2020.104466. hal-02902631 HAL Id: hal-02902631 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02902631 Submitted on 20 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Thermochronology of the highest Central Asian massifs 2 (Khan Tengri - Pobedi, SE Kyrgyztan): evidence for Late 3 Miocene (ca. 8 Ma) reactivation of Permian faults and 4 insights into building the Tian Shan 5 a* b c d c e f 6 Rolland, Y. , Jourdon, A. , Petit, C. , Bellahsen, N. , Loury, C. -

EUROPE a Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania

EUROPE A Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania o The country's largest museum. It was opened on 28 October 1981 and is 27,000 square meters in size, while 18,000 square meters are available for expositions. The National Historical Museum includes the following pavilions: Pavilion of Antiquity, Pavilion of the Middle Ages, Pavilion of Renaissance, Pavilion of Independence, Pavilion of Iconography, Pavilion of the National Liberation Antifascist War, Pavilion of Communist Terror, and Pavilion of Mother Teresa. • Et'hem Bey Mosque – Tirana, Albania o The Et’hem Bey Mosque is located in the center of the Albanian capital Tirana. Construction was started in 1789 by Molla Bey and it was finished in 1823 by his son Ethem Pasha (Haxhi Ethem Bey), great- grandson of Sulejman Pasha. • Mount Dajt – Tirana, Albania o Its highest peak is at 1,613 m. In winter, the mountain is often covered with snow, and it is a popular retreat to the local population of Tirana that rarely sees snow falls. Its slopes have forests of pines, oak and beech. Dajti Mountain was declared a National Park in 1966, and has since 2006 an expanded area of about 29,384 ha. It is under the jurisdiction and administration of Tirana Forest Service Department. • Skanderbeg Square – Tirana, Albania o Skanderbeg Square is the main plaza of Tirana, Albania named in 1968 after the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. A Skanderbeg Monument can be found in the plaza. • Skanderbeg Monument – Skanderberg Square, Tirana, Albania o The monument in memory of Skanderbeg was erected in Skanderbeg Square, Tirana.