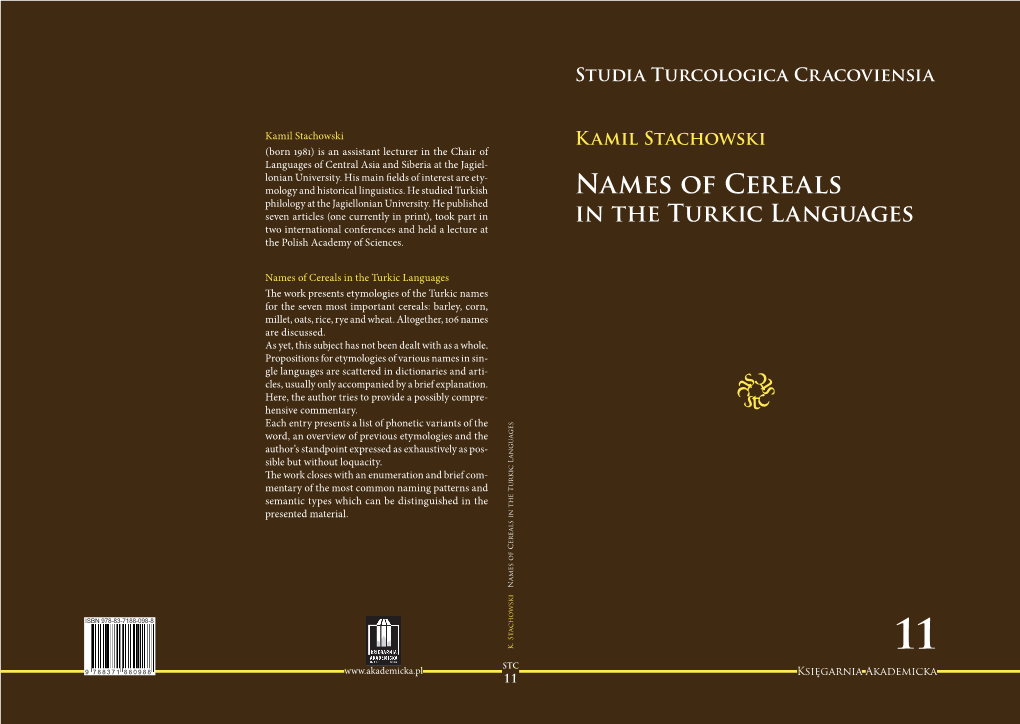

Names of Cereals in the Turkic Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Vol. 2 2020

ISSN 2664-5157 (print) ISSN 2708-7360 (online) №4 Turkic Studies Vol. 2 Journal 2020 Nur-Sultan ISSN (print)2664-5157 ISSN (online)2708-7360 Turkic Studies Journal 2020, Volume 2, Number 4 2019 жылдан бастап шығады Founded in 2019 Издается с 2019 года Жылына 4 рет шығады Published 4 times a year Выходит 4 раза в год Нұр-Сұлтан, 2020 Nur-Sultan, 2020 Нур-Султан, 2020 ISSN 2664-5157. Turkic Studies Journal, 2020, Volume 2, Number 4 1 Бас редакторы: Ерлан Сыдықов, т.ғ.д., проф., ҚР ҰҒА академигі, Л.Н. Гумилев атындағы Еуразия ұлттық университеті (Нұр-Сұлтан, Қазақстан) Бас редактордың орынбасары Шакимашрип Ибраев, ф.ғ.д., проф., Л.Н. Гумилев атындағы Еуразия ұлттық университеті (Нұр-Сұлтан, Қазақстан) Бас редактордың орынбасары Ирина Невская, доктор, проф., Гете университеті (Франкфурт, Германия) Редакция алқасы Ғайбулла Бабаяров т.ғ.д., Өзбекстан ғылым академиясы Ұлттық археология орталығы (Ташкент, Өзбекстан) Ұлданай Бахтикиреева ф.ғ.д., проф., Ресей халықтар достастығы университеті (Мәскеу, Ресей Федерациясы) Дмитрий Васильев т.ғ.д., проф., Ресей ғылым академиясының Шығыстану институты (Мәскеу, Ресей Федерациясы) Гюрер Гульсевин доктор, проф., Эгей университеті (Измир, Түркия) Анна Дыбо ф.ғ.д., проф., Ресей ғылым академиясының Тіл білімі институты (Мәскеу, Ресей Федерациясы) Мырзатай Жолдасбеков ф.ғ.д., проф., Л.Н. Гумилев атындағы Еуразия ұлттық университеті (Нұр-Сұлтан, Қазақстан) Дания Загидуллина ф.ғ.д., проф., Татарстан Республикасы ғылым академиясы (Қазан, Ресей Федерациясы) Зимони Иштван доктор, проф., Сегед университеті (Сегед, Венгрия). Болат Көмеков т.ғ.д., проф., Л.Н. Гумилев атындағы Еуразия ұлттық университеті (Нұр-Сұлтан, Қазақстан) Игорь Кызласов т.ғ.д., проф., Ресей ғылым академиясы Археология институты (Мәскеу, Ресей Федерациясы) Дихан Қамзабекұлы ф.ғ.д., проф., Л.Н. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Declension System of the Turkic Languages: Historical Development of Case Endings Gulgaysha S

Bulletin of the KIH of the RAS, 2016, Vol. 23, Is. 1 Copyright © 2016 by the Kalmyk Institute for Humanities of the Russian Academy of Sciences Published in the Russian Federation Bulletin of the Kalmyk Institute for Humanities of the Russian Academy of Sciences Has been issued since 2008 ISSN: 2075-7794; E-ISSN: 2410-7670 Vol. 23, Is. 1, pp. 166–173, 2016 DOI 10.22162/2075-7794-2016-23-1-166-173 Journal homepage: http://kigiran.com/pubs/vestnik UDC 811.512.1 Declension System of the Turkic Languages: Historical Development of Case Endings Gulgaysha S. Sagidolda1 1 Ph. D. of Philology, Professor of the Kazakh Linguistics Department at L. N. Gumilyev Eurasian National University (Astana, the Republic of Kazakhstan). E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Declension system of the Turkic languages is characterized by a large number of cases and a variety of forms of cases. The research works indicate the number of cases in the Turkic languages in different ways, in some languages they are considered to be 6, and in the others 7 or 8. There are different opinions about the number of cases in the language of the ancient Turkic written monuments, known as the source of the Turkic languages. Some scholars defi ne 11 cases and some say that the number of main cases is 7. In the language of the Orkhon, Yenisei and Talas monuments there are hidden or null form of cases, as well as the meaning of cases can be given by individual words. Also, some endings correspond with the formants of other cases according to the form or comply with other formants of cases according to the meaning. -

The Imposition of Translated Equivalents to Avoid T

International Humanities Studies Vol. 3 No.1; March 2016 ISSN 2311-7796 On some future tense participles in modern Turkic languages Aynel Enver Meshadiyeva Abstract This paper investigates phonetic and morphological-semantic features and the main functions of the future participle –ası/-esi in modern Turkic languages. At the present time, a series of questions concerning an etymology of the future participle –ası/-esi in the modern Turkic languages does not have a due and exhaustive treatment in the Turkology. In the course of the research, similar and distinctive features of the future participles –ası/-esi in Turkic languages were revealed. It should be noted that comparative-historical researches of the grammatical elements in the modern Turkic languages have gained a considerable scientific meaning and undoubted actuality. The actuality of the paper’s theme is conditioned by these factors. Keywords: Future tense participle –ası/-esi, comparative-historical analysis, etimology, oghuz group, kipchak group, Turkic languages, similar and distinctive features. Introduction This article is devoted to comparative historical analysis of the future tense participle –ası/- esi in modern Turkic languages. The purpose of this article is to study a comparative historical analysis of the future tense participle –ası/-esi in Turkic languages. It also aims to identify various characteristic phonetic, morphological, and syntactic features in modern Turkic languages. This article also analyses materials of different dialects of Turkic languages, and their old written monuments. The results of the detailed etymological analysis of the future tense participle –ası/-esi help to reveal the peculiarities of lexical-semantic and morphological structure of the Turkic languages’ participle. -

Turkic Languages 161

Turkic Languages 161 seriously endangered by the UNESCO red book on See also: Arabic; Armenian; Azerbaijanian; Caucasian endangered languages: Gagauz (Moldovan), Crim- Languages; Endangered Languages; Greek, Modern; ean Tatar, Noghay (Nogai), and West-Siberian Tatar Kurdish; Sign Language: Interpreting; Turkic Languages; . Caucasian: Laz (a few hundred thousand speakers), Turkish. Georgian (30 000 speakers), Abkhaz (10 000 speakers), Chechen-Ingush, Avar, Lak, Lezghian (it is unclear whether this is still spoken) Bibliography . Indo-European: Bulgarian, Domari, Albanian, French (a few thousand speakers each), Ossetian Andrews P A & Benninghaus R (1989). Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert (a few hundred speakers), German (a few dozen Verlag. speakers), Polish (a few dozen speakers), Ukranian Aydın Z (2002). ‘Lozan Antlas¸masında azınlık statu¨ su¨; (it is unclear whether this is still spoken), and Farklı ko¨kenlilere tanınan haklar.’ In Kabog˘lu I˙ O¨ (ed.) these languages designated as seriously endangered Azınlık hakları (Minority rights). (Minority status in the by the UNESCO red book on endangered lan- Treaty of Lausanne; Rights granted to people of different guages: Romani (20 000–30 000 speakers) and Yid- origin). I˙stanbul: Publication of the Human Rights Com- dish (a few dozen speakers) mission of the I˙stanbul Bar. 209–217. Neo-Aramaic (Afroasiatic): Tu¯ ro¯ yo and Su¯ rit (a C¸ag˘aptay S (2002). ‘Otuzlarda Tu¨ rk milliyetc¸ilig˘inde ırk, dil few thousand speakers each) ve etnisite’ (Race, language and ethnicity in the Turkish . Languages spoken by recent immigrants, refugees, nationalism of the thirties). In Bora T (ed.) Milliyetc¸ilik ˙ ˙ and asylum seekers: Afroasiatic languages: (Nationalism). -

History of the Turkish People

June IJPSS Volume 2, Issue 6 ISSN: 2249-5894 2012 _________________________________________________________ History of the Turkish people Vahid Rashidvash* __________________________________________________________ Abstract The Turkish people also known as "Turks" (Türkler) are defined mainly as being speakers of Turkish as a first language. In the Republic of Turkey, an early history text provided the definition of being a Turk as "any individual within the Republic of Turkey, whatever his faith who speaks Turkish, grows up with Turkish culture and adopts the Turkish ideal is a Turk." Today the word is primarily used for the inhabitants of Turkey, but may also refer to the members of sizeable Turkish-speaking populations of the former lands of the Ottoman Empire and large Turkish communities which been established in Europe (particularly in Germany, France, and the Netherlands), as well as North America, and Australia. Key words: Turkish people. History. Culture. Language. Genetic. Racial characteristics of Turkish people. * Department of Iranian Studies, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, Republic of Armeni. A Monthly Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International e-Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage, India as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A. International Journal of Physical and Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us 118 June IJPSS Volume 2, Issue 6 ISSN: 2249-5894 2012 _________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction The Turks (Turkish people), whose name was first used in history in the 6th century by the Chinese, are a society whose language belongs to the Turkic language family (which in turn some classify as a subbranch of Altaic linguistic family. -

Studies in Honour of Éva Kincses-Nagy

ALTAIC AND CHAGATAY LECTURES Studies in Honour of Éva Kincses-Nagy Altaic and Chagatay Lectures Studies in Honour of Éva Kincses-Nagy Edited by István Zimonyi Szeged – 2021 This publication was supported by the ELTE-SZTE Silk Road Research Group, ELKH Cover illustration: Everyone acts according to his own disposition (Q 17,84, written in nasta’liq) Calligraphy of Mustafa Khudair Letters and Words. Exhibtion of Arabic Calligraphy. Cairo 2011, 35. © University of Szeged, Department of Altaic Studies, Printed in 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the author or the publisher. Printed by: Innovariant Ltd., H-6750 Algyő, Ipartelep 4. ISBN: 978 963 306 793 2 (printed) ISBN: 978 963 306 794 9 (pdf) Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. 11 ŞÜKRÜ HALÛK AKALIN On the Etymology and Word Formation of Arıbeyi ‘Queen Bee’: How did the Female Bee Become Bey ‘Male Ruler’ in Turkish? ....................... 15 KUTSE ALTIN The Reconstruction of the Motives and Activities of the Last Campaign of Kanuni Sultan Süleyman ........................................................ 21 TATIANA A. ANIKEEVA The Tale of the Epic Cycle of “Kitab-i Dedem Korkut” in Turkish Folklore of the 20th Century ................................................................... 43 İBRAHIM AHMET AYDEMIR Zur Typologie von „Small Clauses” in modernen Türksprachen ........................ 51 LÁSZLÓ BALOGH Notes on the Ethnic and Political Conditions of the Carpathian Basin in the Early 9th Century ........................................................... 61 JÚLIA BARTHA Turkish Heritage of Hungarian Dietary Culture .................................................. 71 BÜLENT BAYRAM An Epic about Attila in Chuvash Literature: Attilpa Krimkilte ......................... -

Scientific Research of the SCO Countries: Synergy and Integration”

上合组织国家的科学研究:协同和一体化 国际会议 参与者的英文报告 International Conference “Scientific research of the SCO countries: synergy and integration” Part 1: Participants’ reports in English 2018年6月29-30日 中国北京 June 29-30, 2018. Beijing, PRC Materials of the International Conference “Scientific research of the SCO countries: synergy and integration” - Reports in English (June 29-30, 2018. Beijing, PRC) ISBN 978-5-905695-70-4 这些会议文集结合了会议的材料 - 研究论文和科学工作 者的论文报告。 它考察了职业化人格的技术和社会学问题。 一些文章涉及人格职业化研究问题的理论和方法论方法和原 则。 作者对所引用的出版物,事实,数字,引用,统计数据, 专有名称和其他信息的准确性负责 These Conference Proceedings combines materials of the conference – research papers and thesis reports of scientific workers. It examines tecnical and sociological issues of professionalization personality. Some articles deal with theoretical and methodological approaches and principles of research questions of personality professionalization. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of cited publications, facts, figures, quotations, statistics, proper names and other information. ISBN 978-5-905695-70-4 ©Minzu University of China, 2018 ©Scientific publishing house Infinity, 2018 © Group of authors, 2018 CONTENT ECONOMY 经济系统稳定性建模 Modeling of the economic systems stability Toroptsev Evgeny Lvovich, Marahovskiy Alexander Sergeevitch.........................13 现代人事管理系统中雇主的人力资源品牌 HR-brand of the employer in the modern system of personnel management Rakhimov Ildar Khaybullovich, Perevozova Ol’ga Vladimirovna .......................22 目标客户群分析在“Kazpromkomplex”LLP Target client group analysis at “Kazpromkomplex” LLP Islamgaleyev -

Abstracts English

International Symposium: Interaction of Turkic Languages and Cultures Abstracts Saule Tazhibayeva & Nevskaya Irina Turkish Diaspora of Kazakhstan: Language Peculiarities Kazakhstan is a multiethnic and multi-religious state, where live more than 126 representatives of different ethnic groups (Sulejmenova E., Shajmerdenova N., Akanova D. 2007). One-third of the population is Turkic ethnic groups speaking 25 Turkic languages and presenting a unique model of the Turkic world (www.stat.gov.kz, Nevsakya, Tazhibayeva, 2014). One of the most numerous groups are Turks deported from Georgia to Kazakhstan in 1944. The analysis of the language, culture and history of the modern Turkic peoples, including sub-ethnic groups of the Turkish diaspora up to the present time has been carried out inconsistently. Kazakh researchers studied history (Toqtabay, 2006), ethno-political processes (Galiyeva, 2010), ethnic and cultural development of Turkish diaspora in Kazakhstan (Ibrashaeva, 2010). Foreign researchers devoted their studies to ethnic peculiarities of Kazakhstan (see Bhavna Dave, 2007). Peculiar features of Akhiska Turks living in the US are presented in the article of Omer Avci (www.nova.edu./ssss/QR/QR17/avci/PDF). Features of the language and culture of the Turkish Diaspora in Kazakhstan were not subjected to special investigation. There have been no studies of the features of the Turkish language, with its sub- ethnic dialects, documentation of a corpus of endangered variants of Turkish language. The data of the pre-sociological surveys show that the Kazakh Turks self-identify themselves as Turks Akhiska, Turks Hemshilli, Turks Laz, Turks Terekeme. Unable to return to their home country to Georgia Akhiska, Hemshilli, Laz Turks, Terekeme were scattered in many countries. -

Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map

SVENSKA FORSKNINGSINSTITUTET I ISTANBUL SWEDISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE IN ISTANBUL SKRIFTER — PUBLICATIONS 5 _________________________________________________ Lars Johanson Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul Stockholm 2001 Published with fõnancial support from Magn. Bergvalls Stiftelse. © Lars Johanson Cover: Carte de l’Asie ... par I. M. Hasius, dessinée par Aug. Gottl. Boehmius. Nürnberg: Héritiers de Homann 1744 (photo: Royal Library, Stockholm). Universitetstryckeriet, Uppsala 2001 ISBN 91-86884-10-7 Prefatory Note The present publication contains a considerably expanded version of a lecture delivered in Stockholm by Professor Lars Johanson, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, on the occasion of the ninetieth birth- day of Professor Gunnar Jarring on October 20, 1997. This inaugu- rated the “Jarring Lectures” series arranged by the Swedish Research Institute of Istanbul (SFII), and it is planned that, after a second lec- ture by Professor Staffan Rosén in 1999 and a third one by Dr. Bernt Brendemoen in 2000, the series will continue on a regular, annual, basis. The Editors Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map Linguistic documentation in the field The topic of the present contribution, dedicated to my dear and admired colleague Gunnar Jarring, is linguistic fõeld research, journeys of discovery aiming to draw the map of the Turkic linguistic world in a more detailed and adequate way than done before. The survey will start with the period of the classical pioneering achievements, particu- larly from the perspective of Scandinavian Turcology. It will then pro- ceed to current aspects of language documentation, commenting brief- ly on a number of ongoing projects that the author is particularly fami- liar with. -

List of Publications

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS BOOKS 2016 Altuigurische Aparimitāyus-Literatur und kleinere tantrische Texte. (Berliner Turfantexte XXXVI). Turnhout: Brepols, 234 Pp. + 10 Plates. Gudai Weiwueryu zanshi he miaoxiexing shige de yuwenxue yanjiu [Old Uyghur hymns and praises]. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics, XIV + 482 Pp. + 50 Plates. 2015 Gudai Weiwueryu zanshi he miaoxiexing shige de yuwenxue yanjiu [Old Uyghur hymns and praises]. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics, XIV + 482 Pp. + 50 Plates. [With Masahiro Shōgaito, Setsu Fujishiro, Noriko Ohsaki and Mutsumi Sugahara] The Berlin Chinese text U 5335 written in Uighur script. A reconstruction of the Inherited Uighur Pronunciation of Chinese. (Berliner Turfantexte XXXIV.) Turnhout: Brepols, 208 Pp. + 7 Plates. 2010 Prajñāpāramitā Literature in Old Uyghur. (Berliner Turfantexte XXVIII.) Turnhout: Brepols, 319 Pp. + 23 Plates. 2009 Alttürkische Handschriften Teil 15: Die uigurischen Blockdrucke der Berliner Turfansammlung. Teil 3: Stabreimdichtungen, Kalendarisches, Bilder, unbestimmte Fragmente und Nachträge. (Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland, Bd. XIII 23.) Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 309 Pp. 2008 Alttürkische Handschriften Teil 12: Die uigurischen Blockdrucke der Berliner Turfansammlung. Teil 2: Apokryphen, Mahāyāna-Sūtren, Erzählungen, Magische Texte, Kommentare und Kolophone. (Verzeichnis der Orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland, Bd. XIII 20.) Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 264 Pp. 2007 Alttürkische Handschriften. Teil 11: Die uigurischen Blockdrucke der Berliner Turfansammlung. Teil 1: Tantrische Texte (VOHD XIII,19.). Beschrieben von Abdurishid Yakup und M. Knüppel. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 258 Pp. [Catalogue, technical remarks, blibliography and indexes (Pp. 27-258) are by A. Yakup] 2006 Dišastvustik: Eine altuigurische Bearbeitung einer Legende aus dem Catuṣpariṣat-sūtra. (Veröffentlichungen der Societas Uralo-Altaica 71.) Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. VIII + 176 Pp. 2005 The Turfan dialect of Uyghur. -

DOI: 10.22378/2313-6197.2018-6-1 ISSN 2313-6197 (Online) ISSN 2308-152X (Print) ЗОЛОТООРДЫНСКОЕ ОБОЗРЕНИЕ 2018

DOI: 10.22378/2313-6197.2018-6-1 ISSN 2313-6197 (Online) ISSN 2308-152X (Print) ЗОЛОТООРДЫНСКОЕ ОБОЗРЕНИЕ 2018. Том 6, № 1 ZOLOTOORDYNSKOE OBOZRENIE= G OLDEN H ORDE R EVIEW 2018. Vol. 6, no. 1 Научный журнал Academic Journal УЧРЕДИТЕЛЬ: FOUNDER: ГБУ «Институт истории State Institution им. Ш. Марджани Академии наук «Sh.Marjani Institute of History Республики Татарстан» of Tatarstan Academy of Sciences» Свидетельство о регистрации СМИ Certificate of registration in the mass media ПИ № ФС77–54682 от 9 июля 2013 г. ПИ № ФС77–54682 given by Roskomnadzor выдано Роскомнадзором on 9 July 2013 Журнал основан в апреле 2013 г. Journal was founded in April 2013 Выходит 4 раза в год Published 4 times a year РЕДАКЦИЯ: EDITORIAL OFFICE: 420014, г. Казань, Кремль, подъезд 5 (юрид.) 420014, Kazan, Kremlin, entrance 5 (juridical) 420111, г. Казань, ул. Батурина, 7 420111, Kazan, Baturin Str., 7 Тел./факс (843) 292 84 82 (приемная), Tel./Fax (843) 292 84 82 (reception), 292 00 19 292 00 19 Подписной индекс в каталоге Subscription index in the «Catalogue «Каталог Российской Прессы» – 31999 of the Russian Press» – 31999 ЖУРНАЛ ИНДЕКСИРУЕТСЯ В: THE JOURNAL IS INDEXED BY: Scopus Scopus Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory Российский индекс научного Russian Science Citation цитирования (РИНЦ), РГБ Index Database, RSL AcademicKeys, ResearchBib, WorldCat AcademicKeys, ResearchBib, WorldCat Научная электронная библиотека Scientific Electronic Open Access открытого доступа КиберЛенинка Library CyberLeninka Google Scholar, СОЦИОНЕТ Google Scholar, SOCIONET Журнал входит в Перечень российских рецензируемых научных журналов, в которых должны быть опубликованы основные научные результаты диссертаций на соискание ученых степеней доктора и кандидата наук (список научных журналов ВАК МОиН РФ) http://goldhorde.ru E-mail: [email protected] © ГБУ «Институт истории им.