IDENTITY, IDEOLOGY, and LANGUAGE SHIFT: a Sociolinguistic Study of Magahi Immigrants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

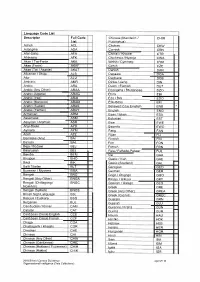

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code List Acholi ACL Adangme

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code Chinese (Mandarin I CHIM List Putonqhua) Acholi ACL Chokwe CKW Adangme ADA Cornish CRN Afar-Saha AFA Chitrali I Khowar CTR Afrikaans AFK Chichewa I Nyanja CWA Akan I Twi-Fante AKA Welsh I Cymraeg CYM Akan (Fante) AKAF Czech CZE Akan (Twi I Asante) AKAT Danish DAN Albanian I Shqip ALB Dagaare DGA Alur ALU Dagbane DGB Amharic AMR Dinka I Jieng DIN Arabic ARA Dutch I Flemish OUT Arabic (Any Other) ARAA Dzongkha I Bhutanese DZO Arabic (Algeria) ARAG Ebira EBI Arabic (Iraq) ARAI Eda I Bini EDO Arabic (Morocco) ARAM Efik-lbibio EFI Arabic (Sudan) ARAS Believed to be English ENB * Arabic (Yemen) ARAY English ENG * Armenian ARM Esan / lshan ESA Assamese ASM Estonian EST Assyrian I Aramaic ASR Ewe EWE Anyi-Baule AYB Ewondo EWO Aymara AYM Fang FAN Azeri AZE Fijian FIJ Bamileke (Any) BAI Finnish FIN Balochi BAL Fon FON Beja I Bedawi BEJ French FRN Belarusian BEL Fula I Fulfulde-Pulaar FUL Bemba BEM Ga GAA Bhojpuri BHO Gaelic / Irish GAE Bikol BIK Gaelic (Scotland) GAL Balti Tibetan BLT Georgian GEO Burmese I Myanma BMA German GER Bengali BNG Gago I Chigogo GGO Bengali (Any Other) BNGA Kikuyu I Gikuyu GKY Bengali (Chittagong I BNGC Galician I Galego GLG Noakhali) Greek GRE Bengali (Sylheti) BNGS Greek (Any Other) GREA British Sign Language BSL Greek (Cyprus) GREC Basque I Euskara BSQ Guarani GRN Bulgarian BUL Gujarati GUJ Cambodian I Khmer CAM Gurenne I Frafra GUN Catalan CAT Gurma GUR Caribbean Creole English CCE Hausa HAU Caribbean Creole French CCF Hindko HOK Chaga CGA Hebrew HEB Chattisgarhi I Khatahi CGR -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Particle '-Wa' and Its Various Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Implications In

Interdisciplinary Journal of Linguistics (IJL Vol .9) Interdisciplinary Journal of Linguistics Volume [9] 2016, Pp.150-162 Particle ‘-wA’ and its Various Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Implications in Magahi Chandan Kumar * Abstract Magahi is one of the Indo-Aryan languages spoken predominantly in Bihar. Though the language is considered as a dialect of Hindi on the basis of the lexical similarities, it differs from Hindi on a large scale, structurally. The language demonstrates some of the distinctive linguistic features which are not widespread in Indo-Aryan languages e.g., the three -way number distinction, the constraint on plural system, the agreement in honorific, negation system, the presence of multiple determiner, over bound definite determiner with proper noun etc. Noun in Magahi usually accompanies with a particle that can be called a discourse particle because of its nature of occurrence in the discourse only. The particle does not occur with the noun outside the discourse. The ‘elsewhere’ form of the discourse particle is ‘-wA’ which was considered to have no semantics earlier. There are three forms of the particle which are in complementary distribution and are phonologically conditioned. The variant forms of the particle are ‘-wA’, ‘-A’ and ‘-yA’. The particle in all its forms functions as definite marker or specificity marker. No work has been done to value the kind of function this particle performs in the language’s structure. This paper is an attempt to describe the use of the particle ‘-wA’ and its various linguistic and social implications and its speech community. 1. Introduction Magahi is one of the Indo-Aryan languages spoken predominantly in Bihar. -

Collecting and Recording Data on Pupils' First Language

Collecting and recording data on pupils’ first language Guidance Welsh Assembly Government Circular No: 001/2011 Date of issue: January 2011 Collecting and recording data on pupils’ first language Audience All maintained schools, local authorities. Overview This guidance provides new advice on the collection and recording of data on pupils’ first languages. Action The collection and recording of data on pupils’ first languages required in School Management Information Systems, based on the new standard language category list at Annex A. Further Theresa Davies information Support for Learners Division Department for Children, Education, Lifelong Learning and Skills Welsh Assembly Government Cathays Park Cardiff CF10 3NQ Tel: 029 2082 1658 Fax: 029 2082 1044 e-mail: [email protected] Additional Further copies of this document can be obtained at the above copies address. This document can be accessed from the Welsh Assembly Government website at www.wales.gov.uk/educationandskills Related The Learning Country: Vision into Action (2006) documents Inclusion and Pupil Support National Assembly for Wales Circular No: 47/2006 (2006) Collecting and Recording Data on Pupils’ Ethnic Background Welsh Assembly Government Circular No: 006/2009 (2009) ISBN 978 0 7504 5907 5 © Crown copyright 2011 WAG10-10792 F5291011 Contents Summary 2 Section 1: Introduction and policy context 4 Section 2: Reasons for first language data collection in Wales 6 Section 3: Benefits of collecting first language data 10 Section 4: Information -

International Journal of the Sociology of Language

IJSL 2018; 252: 97–123 Hannah Carlan* “In the mouth of an aborigine”: language ideologies and logics of racialization in the Linguistic Survey of India https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2018-0016 Abstract: The Linguistic Survey of India (LSI),editedandcompiledbyGeorge Abraham Grierson, was the first systematic effort by the British colonial gov- ernment to document the spoken languages and dialects of India. While Grierson advocated an approach to philology that dismissed the affinity of language to race, the LSI mobilizes a complex, intertextualsetofracializing discourses that form the ideological ground upon which representations of language were constructed and naturalized. I analyze a sub-set of the LSI’s volumes in order to demonstrate how Grierson’s linguistic descriptions and categorizations racialize minority languages and their speakers as corrupt, impure, and uncivilized. I highlight how semiotic processes in the text con- struct speakers as possessing essential “ethnic” characteristics that are seen as indexical of naturalized linguistic differences. I argue that metapragmatic statements within descriptions of languages and dialects are made possible by ethnological discourses that ultimately reinforce an indexical relationship between language and race. This analysis of the survey sheds light on the centrality of language in colonial constructions of social difference in India, as well as the continued importance of language as a tool for legitimating claims for political recognition in postcolonial India. Keywords: language surveys, language ideologies, racialization, British colonialism, India 1 Introduction The Linguistic Survey of India (1903–1928), hereafter the LSI, was the first attempt to capture the spoken languages and dialects of British India as part of the wider goal of the colonial government to learn, through bureaucratic documentation, about the social makeup of its subjects. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

The Indo-Aryan Languages: a Tour of the Hindi Belt: Bhojpuri, Magahi, Maithili

1.2 East of the Hindi Belt The following languages are quite closely related: 24.956 ¯ Assamese (Assam) Topics in the Syntax of the Modern Indo-Aryan Languages February 7, 2003 ¯ Bengali (West Bengal, Tripura, Bangladesh) ¯ Or.iya (Orissa) ¯ Bishnupriya Manipuri This group of languages is also quite closely related to the ‘Bihari’ languages that are part 1 The Indo-Aryan Languages: a tour of the Hindi belt: Bhojpuri, Magahi, Maithili. ¯ sub-branch of the Indo-European family, spoken mainly in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldive Islands by at least 640 million people (according to the 1.3 Central Indo-Aryan 1981 census). (Masica (1991)). ¯ Eastern Punjabi ¯ Together with the Iranian languages to the west (Persian, Kurdish, Dari, Pashto, Baluchi, Ormuri etc.) , the Indo-Aryan languages form the Indo-Iranian subgroup of the Indo- ¯ ‘Rajasthani’: Marwar.i, Mewar.i, Har.auti, Malvi etc. European family. ¯ ¯ Most of the subcontinent can be looked at as a dialect continuum. There seem to be no Bhil Languages: Bhili, Garasia, Rathawi, Wagdi etc. major geographical barriers to the movement of people in the subcontinent. ¯ Gujarati, Saurashtra 1.1 The Hindi Belt The Bhil languages occupy an area that abuts ‘Rajasthani’, Gujarati, and Marathi. They have several properties in common with the surrounding languages. According to the Ethnologue, in 1999, there were 491 million people who reported Hindi Central Indo-Aryan is also where Modern Standard Hindi fits in. as their first language, and 58 million people who reported Urdu as their first language. Some central Indo-Aryan languages are spoken far from the subcontinent. -

Magahi and Magadh: Language and People

G.J.I.S.S.,Vol.3(2):52-59 (March-April, 2014) ISSN: 2319-8834 MAGAHI AND MAGADH: LANGUAGE AND PEOPLE Lata Atreya1 , Smriti Singh2, & Rajesh Kumar3 1Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Patna, Bihar, India 2Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Patna, Bihar, India 3Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Tamil Nadu, India Abstract Magahi is an Indo-Aryan language, spoken in Eastern part of India. It is genealogically related to Magadhi Apbhransha, once having the status of rajbhasha, during the reign of Emperor Ashoka. The paper outlines the Magahi language in historical context along with its present status. The paper is also a small endeavor to capture the history of Magadh. The paper discusses that once a history of Magadh constituted the history of India. The paper also attempts to discuss the people and culture of present Magadh. Keywords: Magahi, Magadhi Apbhransha, Emperor Ashoka. 1 Introduction The history of ancient India is predominated by the history of Magadh. Magadh was once an empire which expanded almost till present day Indian peninsula excluding Southern India. Presently the name ‘Magadh’ is confined to Magadh pramandal of Bihar state of India. The prominent language spoken in Magadh pramandal and its neighboring areas is Magahi. This paper talks about Magahi as a language, its history, geography, script and its classification. The paper is also a small endeavor towards the study of the history of ancient Magadh. The association of history of Magadh with the history and culture of ancient India is outlined. -

Plurality in Magahi and Reference to Count/Mass Noun

Plurality in Magahi Language and Reference to count/mass Noun Chandan Kumar PhD Research Scholar, JNU, New Delhi Abstract The concept of the reference of number system in the language is particularized due to the different linguistic ecology. The perception particularly in the domain of additive plural, however, is not very arbitrary. A limited number of possibilities have been identified cross- linguistically; most of the languages follow two-way distinction i.e. singular versus plural. Some languages, particularly, classifier morphologically have inbuilt three-way number distinction. Magahi, a new Indo-Aryan language, uses morpho-phonetic way to mark plurality, and is purely a nominal phenomenon1. Magahi has two forms of noun, and marked noun carries ‘identifiability’ or ‘uniqueness’ property (Lyons 1999). For the present pupose, we entitle this marker as ‘discourse marker/definite determiner’2. The paper following Corbett (2000) discusses how Magahi makes three-way number distinction. The three-way number distinction is based on the fact that the marked noun in Magahi, strictly, is singular (following Jespersen 1924; Corbett 2000, etc.). Obligatoriness/optionality of the system is discussed following Drayer (2013). The plural mechanism shows a restricted regular pattern on the animacy hierarchy3. Despite having the obligatory numeral classifier system; it has regular plural system which seems to be problematic for the observation made in Aikhenvald (2000) that classifier languages don’t have regular plural system. With only few exceptions like abstract noun, mass noun, etc. the system of plurality is regular in the language. Magahi also distinguishes between the bare plural [N+PL] and marked plural [[N+DEF] +PL]]; marked plural deriving the semantics from marked singular has semantics of familiarity, identifiability, presupposition, etc.