International Journal of the Sociology of Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Linguistic Survey of India Bihar

LINGUISTIC SURVEY OF INDIA BIHAR 2020 LANGUAGE DIVISION OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA i CONTENTS Pages Foreword iii-iv Preface v-vii Acknowledgements viii List of Abbreviations ix-xi List of Phonetic Symbols xii-xiii List of Maps xiv Introduction R. Nakkeerar 1-61 Languages Hindi S.P. Ahirwal 62-143 Maithili S. Boopathy & 144-222 Sibasis Mukherjee Urdu S.S. Bhattacharya 223-292 Mother Tongues Bhojpuri J. Rajathi & 293-407 P. Perumalsamy Kurmali Thar Tapati Ghosh 408-476 Magadhi/ Magahi Balaram Prasad & 477-575 Sibasis Mukherjee Surjapuri S.P. Srivastava & 576-649 P. Perumalsamy Comparative Lexicon of 3 Languages & 650-674 4 Mother Tongues ii FOREWORD Since Linguistic Survey of India was published in 1930, a lot of changes have taken place with respect to the language situation in India. Though individual language wise surveys have been done in large number, however state wise survey of languages of India has not taken place. The main reason is that such a survey project requires large manpower and financial support. Linguistic Survey of India opens up new avenues for language studies and adds successfully to the linguistic profile of the state. In view of its relevance in academic life, the Office of the Registrar General, India, Language Division, has taken up the Linguistic Survey of India as an ongoing project of Government of India. It gives me immense pleasure in presenting LSI- Bihar volume. The present volume devoted to the state of Bihar has the description of three languages namely Hindi, Maithili, Urdu along with four Mother Tongues namely Bhojpuri, Kurmali Thar, Magadhi/ Magahi, Surjapuri. -

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

Language Surveys in Developing Nations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 170 FL 006 842 AUTHOR Ohannessian, Sirirpi, Ed.; And Others TITLE Language Surveys in Developing Nations. Papersand Reports on Sociolinguistic Surveys. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 227p. AVAILABLE FROMCenter for Applied Linguistics,1611 North Kent Street, Arlington, Virginia 22209($8.50) EDRS PRICE Mr-$0.76 RC Not Available from EDRS..PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Developing Nations; Evaluation Methods; Language Patterns; Language Planning: *LanguageResearch; Language Role; *Language Usage;Nultilingualism; Official Languages; Public Policy;Sociocultural Patterns; *Sociolinguistics; *Surveys ABSTRACT This volume is a selection of papers preparedfor a conference on sociolinguistically orientedlanguage surveys organized by the Center for Applied Linguisticsand held in New York in September 1971. The purpose of theconference vas to review the role and function of such language surveysin the light of surveys conducted in recent years. The selectionis intended to give a general picture of such surveys to thelayman and to reflect the aims of the conference. The papers dealwith scope, problems, uses, organization, and techniques of surveys,and descriptions of particular surveys, and are mostly related tothe Eastern Africa Survey. The authors of theseselections are: Charles A. Ferguson, Ashok R. Kelkar, J. Donald Bowen, Edgar C.Polorm, Sitarpi Ohannessiam, Gilbert Ansre, Probodh B.Pandit, William D. Reyburn, Bonifacio P. Sibayan, Clifford H. Prator,Mervyn C. Alleyne, M. L. Bender, R. L. Cooper aLd Joshua A.Fishman. (Author/AN) Ohannessian, Ferquson, Polonic a a Center for Applied Linqirktie,, mit Language Surveys in Developing Nations papersand reportson sociolinguisticsurveys 2a Edited by Sirarpi Ohannessian, Charles A. Ferguson and Edgar C. Polomd Language Surveysin Developing Nations CY tie papers and reports on 49 LL sociolinguisticsurveys U S OE P MAL NT OF NEAL spt PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETMIT. -

A Language Without a State: Early Histories of Maithili Literature

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT A STATE: EARLY HISTORIES OF MAITHILI LITERATURE Lalit Kumar When we consider the more familiar case of India’s new national language, Hindi, in relation to its so-called dialects such as Awadhi, Brajbhasha, and Maithili, we are confronted with the curious image of a thirty-year-old mother combing the hair of her sixty-year-old daughters. —Sitanshu Yashaschandra The first comprehensive history of Maithili literature was written by Jayakanta Mishra (1922-2009), a professor of English at Allahabad University, in two volumes in 1949 and 1950, respectively. Much before the publication of this history, George Abraham Grierson (1851- 1941), an ICS officer posted in Bihar, had first attempted to compile all the available specimens of Maithili literature in a book titled Maithili Chrestomathy (1882).1 This essay analyses Jayakanta Mishra’s History in dialogue with Grierson’s Chrestomathy, as I argue that the first history of Maithili literature was the culmination of the process of exploration of literary specimens initiated by Grierson, with the stated objective of establishing the identity of Maithili as an independent modern Indian language.This journey from Chrestomathy to History, or from Grierson to Mishra,helps us understand not only the changes Maithili underwent in more than sixty years but also comprehend the centrality of the language-dialect debate in the history of Maithili literature. A rich literary corpus of Maithili created a strong ground for its partial success, not in the form of Mithila getting the status of a separate state, but in the official recognition by the Sahitya Akademi in 1965 and by the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution in 2003. -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

Language Attrition: the Next Phase Barbara Köpke, Monika Schmid

Language Attrition: The next phase Barbara Köpke, Monika Schmid To cite this version: Barbara Köpke, Monika Schmid. Language Attrition: The next phase. Monika S. Schmid, Barbara Köpke, Merel Keijzer, Lina Weilemar. First Language Attrition: Interdisciplinary perspectives on methodological issues, John Benjamins, pp.1-43, 2004, Studies in Bilingualism, 9027241392. hal- 00879106 HAL Id: hal-00879106 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00879106 Submitted on 31 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Language Attrition: The Next Phase Barbara Köpke (Université de Toulouse – Le Mirail) and Monika S. Schmid Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Barbara Köpke Laboratoire de Neuropsycholinguistique Jacques Lordat Institut des Sciences du Cerveau de Toulouse Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail 31058 Toulouse Cedex France [email protected] Monika S. Schmid Engelse Taal en Cultuur Faculteit der Letteren Vrije Universiteit 1081 HV Amsterdam The Netherlands [email protected] Published in : M.S. Schmid, B. Köpke, M. Keijzer & L. Weilemar (2004). First Language Attrition. Interdisciplinary perspectives on methodological issues (pp. 1-43). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Köpke, B. & Schmid, M.S. (2004). Language Attrition: The Next Phase. In M.S. Schmid, B. -

002.Alex.Comitato.2A Bozza

Xaverio Ballester /A/ Y EL VOCALISMO INDOEUROPEO Negli últimi quarant’anni la linguística indo- europea si è in gran parte perduta dietro al mito delle laringali, di cui non intendo tenere alcun conto, e dello strutturalismo, di cui ten- go un conto molto limitato. Giuliano Bonfante, I dialetti indoeuropei, p. 8 De la regla a la ley o de mal en peor Bien digna de mención entre las primerísimas descripciones del mode- lo vocálico indoeuropeo es la propuesta de un inventario fonemático con únicamente tres timbres vocálicos /a i u/, una propuesta empero que fue desgraciadamente y demasiado pronto abandonada, siendo quizá la más conspicua consecuencia de este abandono el hecho de que para la Lin- güística indoeuropea oficialista la ausencia de /a/ devino en la práctica un axioma, de modo que, casi en cualquier posterior propuesta sobre el voca- lismo indoeuropeo, se ha venido adoptando la idea de que no hubiese exis- tido nunca la vocal /a/, y explicándose los ineluctables casos de presencia de /a/ en el material indoeuropeo con variados y bizarros argumentos del tipo de vocalismo despectivo, infantil o popular. Sin embargo, si conside- rada hoy spregiudicatamente, la argumentación que motivó el desalojo de la primitiva /a/ indoeuropea no presenta, al menos desde una perspectiva fonotipológica hodierna, ninguna validez en absoluto. Invocaremos un testimonio objetivo del tema para exponer brevemen- te la cuestión. Escribía O. Szemerényi: «Sotto l’impressione dell’arcai- cità del sanscrito, i fondatori dell’indoeuropeistica e i loro immediati suc- cessori pensavano che il sistema triangolare del sanscrito i–a–u rappre- sentasse la situazione originaria. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

List of Books Available on Calibre Software

LIST OF BOOKS AVAILABLE ON CALIBRE SOFTWARE (PLEASE CONTACT LIBRARY STAFF TO ACCESS CALIBRE) 1. 1.doc · Kamal Swaroop 2. 50 Volume RGS Journal Table of Contents s · Unknown 3. 1836 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 4. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 : THE HISTORY, THE ANTIQUITIES, THE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND LITERATURE ASIA . · Asiatic Society, Calcutta 5. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 6. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 7. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 8. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 9 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 9. 1856 JASB Index AR 19 to JASB 23 · Unknown 10. 1856 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 24 s+m · Unknown 11. 1862 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 30 s+m · Unknown 12. 1866 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 34 s+m · Unknown 13. 1867 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 35 s+m · Unknown 14. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 15. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 16. 1951-52.PMD · Unknown 17. 1952-53-(Final).PMD · Unknown 18. 1953-54.pmd · Unknown 19. 1954-55.pmd · Unknown 20. 1955-56.pmd · Unknown 21. 1956-57.pmd · Unknown 22. 1957-58(interim) 1957-58-1958-59 · Unknown 23. 62569973-Text-of-Justice-Soumitra-Sen-s-Defence · Unknown 24. ([Views of the East; Comprising] India, Canton, [And the Shores of the Red Sea · Robert Elliot 25. -

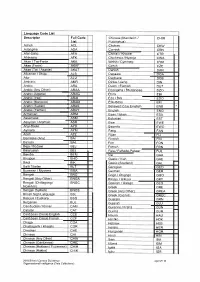

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code List Acholi ACL Adangme

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code Chinese (Mandarin I CHIM List Putonqhua) Acholi ACL Chokwe CKW Adangme ADA Cornish CRN Afar-Saha AFA Chitrali I Khowar CTR Afrikaans AFK Chichewa I Nyanja CWA Akan I Twi-Fante AKA Welsh I Cymraeg CYM Akan (Fante) AKAF Czech CZE Akan (Twi I Asante) AKAT Danish DAN Albanian I Shqip ALB Dagaare DGA Alur ALU Dagbane DGB Amharic AMR Dinka I Jieng DIN Arabic ARA Dutch I Flemish OUT Arabic (Any Other) ARAA Dzongkha I Bhutanese DZO Arabic (Algeria) ARAG Ebira EBI Arabic (Iraq) ARAI Eda I Bini EDO Arabic (Morocco) ARAM Efik-lbibio EFI Arabic (Sudan) ARAS Believed to be English ENB * Arabic (Yemen) ARAY English ENG * Armenian ARM Esan / lshan ESA Assamese ASM Estonian EST Assyrian I Aramaic ASR Ewe EWE Anyi-Baule AYB Ewondo EWO Aymara AYM Fang FAN Azeri AZE Fijian FIJ Bamileke (Any) BAI Finnish FIN Balochi BAL Fon FON Beja I Bedawi BEJ French FRN Belarusian BEL Fula I Fulfulde-Pulaar FUL Bemba BEM Ga GAA Bhojpuri BHO Gaelic / Irish GAE Bikol BIK Gaelic (Scotland) GAL Balti Tibetan BLT Georgian GEO Burmese I Myanma BMA German GER Bengali BNG Gago I Chigogo GGO Bengali (Any Other) BNGA Kikuyu I Gikuyu GKY Bengali (Chittagong I BNGC Galician I Galego GLG Noakhali) Greek GRE Bengali (Sylheti) BNGS Greek (Any Other) GREA British Sign Language BSL Greek (Cyprus) GREC Basque I Euskara BSQ Guarani GRN Bulgarian BUL Gujarati GUJ Cambodian I Khmer CAM Gurenne I Frafra GUN Catalan CAT Gurma GUR Caribbean Creole English CCE Hausa HAU Caribbean Creole French CCF Hindko HOK Chaga CGA Hebrew HEB Chattisgarhi I Khatahi CGR -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern