Puzzling Machines: a Challenge on Learning from Small Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Les Drapeaux Des Langues Construites

Les Drapeaux des Langues Construites Patrice de La Condamine Résumé Depuis toujours, les hommes oscillent entre la préservation de leurs identités particulières et leur besoin d’appartenance à des communautés globales. L’idée d’universel et de recherche de la “fusion des origines” hante leur cœur. Dans cet esprit, des langues construites ont été élaborées. Qu’elles soient à vocation auxiliaire ou internationale, destinées à de vastes aires culturelles ou à but strictement philosophique. Des noms connus comme Volapük, Espéranto, Ido, Bolak, Interlingua, Occidental. Mais aussi Glosa, Kotava, Lingua Franca Nova, Atlango. Ou encore Folskpraat, Slovio, Nordien, Afrihili, Slovianski, Hedšdël. Sans parler du langage philosophique Lojban1. Le plus intéressant est de constater que toutes ces langues ont des drapeaux qui traduisent les messages et idéaux des groupes en question! La connaissance des drapeaux des langues construites est primordiale pour plusieurs raisons: elle nous permet de comprendre que tous les drapeaux sans exception délivrent des messages d’une part; que l’existence des drapeaux n’est pas forcément liée à l’unique notion de territoire d’autre part. Le drapeau est d’abord et avant tout, à travers son dessin et ses couleurs, un “territoire mental”. Après avoir montré et expliqué ces différents drapeaux2, nous conclurons avec la présentation du drapeau des Conlang, sorte d’ONU des Langues construites! Folkspraak Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 1 Sélection de noms parmi d’autres. 2 Une trentaine environ. 175 LES DRAPEAUX DES LANGUES CONSTRUITES introduction A nous tous qui sommes réunis ici pour ce XXIVème Congrès International de la vexillologie à Washington, personne n’a plus besoin d’expliquer la nécessité vitale qu’ont les hommes de se représenter au moyen d’emblèmes, et nous savons la place primordiale qu’occupent les drapeaux dans cette fonction. -

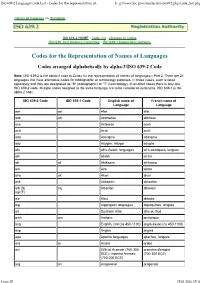

ISO 639-2 Language Code Lis

ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of... h p://www.loc.gov/standards/iso639-2/php/code_list.php Library of Congress >> Standards IS0 639-2 HOME - Code List - Changes to Codes ISO 639 Joint Advisory Committee - ISO 639-1 Registration Authority Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages Codes arranged alphabetically by alpha-3/ISO 639-2 Code Note: ISO 639-2 is the alpha-3 code in Codes for the representation of names of languages-- Part 2. There are 21 languages that have alternative codes for bibliographic or terminology purposes. In those cases, each is listed separately and they are designated as "B" (bibliographic) or "T" (terminology). In all other cases there is only one ISO 639-2 code. Multiple codes assigned to the same language are to be considered synonyms. ISO 639-1 is the alpha-2 code. ISO 639-2 Code ISO 639-1 Code English name of French name of Language Language aar aa Afar afar abk ab Abkhazian abkhaze ace Achinese aceh ach Acoli acoli ada Adangme adangme ady Adyghe; Adygei adyghé afa Afro-Asiatic languages afro-asiatiques, langues afh Afrihili afrihili afr af Afrikaans afrikaans ain Ainu aïnou aka ak Akan akan akk Akkadian akkadien alb (B) sq Albanian albanais sqi (T) ale Aleut aléoute alg Algonquian languages algonquines, langues alt Southern Altai altai du Sud amh am Amharic amharique ang English, Old (ca.450-1100) anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100) anp Angika angika apa Apache languages apaches, langues ara ar Arabic arabe arc Official Aramaic (700-300 araméen d'empire BCE); Imperial Aramaic (700-300 BCE) (700-300 BCE) arg an Aragonese aragonais 1 von 15 15.01.2010 15:16 ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of.. -

In 2018 Linguapax Review

linguapax review6 62018 Languages, Worlds and Action Llengües, mons i acció Linguapax Review 2018 Languages, Worlds and Actions Llengües, mons i acció Editat per: Amb el suport de: Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de Cultura Generalitat de Catalunya Departament d’Acció Exterior Relacions Institucionals i Transparència Secretaria d’Acció Exterior i de la Unió Europea Coordinació editorial: Alícia Fuentes Calle Disseny i maquetació: Maria Cabrera Callís Traduccions: Marc Alba / Violeta Roca Font Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència de Reconeixement-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional de Creative Commons CONTENTS - CONTINGUTS Introduction. Languages, Worlds and action. Alícia Fuentes-Calle 5 Introducció. Llengües, mons i acció. Alícia Fuentes-Calle Túumben Maaya K’aay: De-stigmatising Maya Language in the 14 Yucatan Region Genner Llanes-Ortiz Túumben Maaya K’aay: desestigmatitzant la llengua maia a la regió del Yucatán. Genner Llanes-Ortiz Into the Heimat. Transcultural theatre. Sonia Antinori 37 En el Heimat. Teatre transcultural. Sonia Antinori Sustaining multimodal diversity: Narrative practices from the 64 Central Australian deserts. Jennifer Green La preservació de la diversitat multimodal: els costums narratius dels deserts d’Austràlia central. Jennifer Green A new era in the history of language invention. Jan van Steenbergen 101 Una nova era en la història de la invenció de llengües. Jan van Steenbergen Tribalingual, a startup for endangered languages. Inky Gibbens 183 Tribalingual, una start-up per a llengües amenaçades. Inky Gibbens The Web Alternative, Dimensions of Literacy, and Newer Prospects 200 for African Languages in Today’s World. Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún L’alternativa web, els aspectes de l’alfabetització i les perspectives més recents de les llengües africanes en el món actual. -

Trabajo De Fin De Grado Tiene Como Principal Objetivo Establecer Un Estado De La Cuestión Del Fenómeno Tan Actual De La Creación De Lenguas

Facultad Filosofía y Letras TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Grado de Español: Lengua y Literatura Las técnicas del conlanging. Un capítulo sobre la lingüística aplicada a la creación de lenguas Presentado por D.ª Irene Mata Garrido Tutelado por Prof. Dr. D. José Manuel Fradejas Rueda Índice 1 Introducción .......................................................................................................... 2 2 Esbozo histórico del fenómeno de la invención de lenguas ............................... 4 3 Intento de clasificación de las lenguas artificiales ............................................. 10 4 ¿Cómo crear una lengua? .................................................................................... 13 5 El fenómeno de la invención de lenguas y su dimensión social y artística en la actualidad .......................................................................................................... 21 6 Conclusiones .......................................................................................................... 26 7 Bibliografía ............................................................................................................ 28 8 Apéndice I: recopilación de las lenguas artificiales ........................................... 30 9 Apéndice II: casos de cambios de acento de los actores .................................... 45 1 1 Introducción Los límites de mi lengua son los límites de mi mente. Ludwig Wittgenstein El presente Trabajo de Fin de Grado tiene como principal objetivo establecer un estado de la cuestión -

The Role of Languages in Intercultural Communication Rolo De Lingvoj En Interkultura Komunikado Rola Języków W Komunikacji Międzykulturowej

Cross-linguistic and Cross-cultural Studies 1 The Role of Languages in Intercultural Communication Rolo de lingvoj en interkultura komunikado Rola języków w komunikacji międzykulturowej Editors – Redaktoroj – Redakcja Ilona Koutny & Ida Stria & Michael Farris Poznań 2020 The Role of Languages in Intercultural Communication Rolo de lingvoj en interkultura komunikado Rola języków w komunikacji międzykulturowej 1 2 Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza – Adam Mickiewicz University Instytut Etnolingwistyki – Institute of Ethnolinguistics The Role of Languages in Intercultural Communication Rolo de lingvoj en interkultura komunikado Rola języków w komunikacji międzykulturowej Editors – Redaktoroj – Redakcja Ilona Koutny & Ida Stria & Michael Farris Poznań 2020 3 Cross-linguistic and Cross-cultural Studies 1 Redaktor serii – Series editor: Ilona Koutny Recenzenci: Věra Barandovská-Frank Probal Dasgupta Nicolau Dols Salas Michael Farris Sabine Fiedler Federico Gobbo Wim Jansen Kimura Goro Ilona Koutny Timothy Reagan Ida Stria Bengt-Arne Wickström Projekt okładki: Ilona Koutny Copyright by: Aŭtoroj – Authors – Autorzy Copyright by: Wydawnictwo Rys Wydanie I, Poznań 2020 ISBN 978-83-66666-28-3 DOI 10.48226/978-83-66666-28-3 Wydanie: Wydawnictwo Rys ul. Kolejowa 41 62-070 Dąbrówka tel. 600 44 55 80 e-mail: [email protected] www.wydawnictworys.com 4 Contents – Enhavtabelo – Spis treści Foreword / Antaŭparolo / Przedmowa ................................................................................... 7 1. Intercultural communication: -

PART I: NAME SEQUENCE Name Sequence

Name Sequence PART I: NAME SEQUENCE A-ch‘ang Abor USE Achang Assigned collective code [sit] Aba (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) USE Chiriguano UF Adi Abaknon Miri Assigned collective code [phi] Miśing (Philippine (Other)) Aborlan Tagbanwa UF Capul USE Tagbanua Inabaknon Abua Kapul Assigned collective code [nic] Sama Abaknon (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) Abau Abujhmaria Assigned collective code [paa] Assigned collective code [dra] (Papuan (Other)) (Dravidian (Other)) UF Green River Abulas Abaw Assigned collective code [paa] USE Abo (Cameroon) (Papuan (Other)) Abazin UF Ambulas Assigned collective code [cau] Maprik (Caucasian (Other)) Acadian (Louisiana) Abenaki USE Cajun French Assigned collective code [alg] Acateco (Algonquian (Other)) USE Akatek UF Abnaki Achangua Abia Assigned collective code [sai] USE Aneme Wake (South American (Other)) Abidji Achang Assigned collective code [nic] Assigned collective code [sit] (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) UF Adidji UF A-ch‘ang Ari (Côte d'Ivoire) Atsang Abigar Ache USE Nuer USE Guayaki Abkhaz [abk] Achi Abnaki Assigned collective code [myn] USE Abenaki (Mayan languages) Abo (Cameroon) UF Cubulco Achi Assigned collective code [bnt] Rabinal Achi (Bantu (Other)) Achinese [ace] UF Abaw UF Atjeh Bo Cameroon Acholi Bon (Cameroon) USE Acoli Abo (Sudan) Achuale USE Toposa USE Achuar MARC Code List for Languages October 2007 page 11 Name Sequence Achuar Afar [aar] Assigned collective code [sai] UF Adaiel (South American Indian Danakil (Other)) Afenmai UF Achuale USE Etsako Achuara Jivaro Afghan -

On Tone and Morphophonology of the Akan Reduplication Construction

Alan Reed Libert & Christo Moskovsky 27 Journal of Universal Language 16-2 September 2015, 27-62 Terms for Bodies of Water in A Posteriori and Mixed Artificial Languages Alan Reed Libert & Christo Moskovsky University of Newcastle, Australia Abstract In this paper we look at words for bodies of water (e.g., words for ‘lake’ and ‘river’) in a large number of a posteriori and mixed artificial languages. After presenting the data and briefly discussing some of them, we analyze some aspects of them, including which meanings seem to be more basic than others. For example, words meaning ‘river’ appear to be unmarked with respect to words meaning similar, but smaller, bodies of water (e.g., ‘brook’), since some artificial languages derive the latter from the former, but no languages in our sample derive the latter from the former. This sort of analysis can be applied to other semantic fields in artificial languages. Keywords: a posteriori languages, mixed languages, lexicon Alan Reed Libert School of Humanities & Social Science, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia Phone: 61-2-49215117; Email: [email protected] Christo Moskovsky School of Humanities & Social Science, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia Phone: 61-2-49215163; Email: [email protected] Received August 11, 2015; Revised September 22, 2015; Accepted Septermber 25, 2015 28 Terms for Bodies of Water in A Posteriori and Mixed Artificial Languages 1. Introduction1 Looking at specific areas of the vocabulary of artificial languages (henceforth ALs) can give one an idea of the nature of such languages, at least with respect to the lexicon and perhaps also concerning derivational morphology. -

MARC Code List for Languages

MARC Code List for Languages MARC 21 IBRARY OF CONGRESS ■ 2000 MARC Code List for Languages 2000 Edition Prepared by Network Development and MARC Standards Office Library of Congress LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING DISTRIBUTION SERVICE / WASHINGTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MARC code list for languages / prepared by Network Development and MARC Standards Office, Library of Congress. — 2000 ed. p.cm. Rev. of: USMARC code list for languages. 1996 ed. 1996. ISBN 0-8444-1012-8 1. MARC formats. 2. Language and languages-Code words. I. Library of Congress. Network Development and MARC Standards Office. III. USMARC code list for languages. Z699.35.M28.U79 2000 025.3'16-dc21 00-022744 [Z663.12] Available in the U.S.A. and other countries from: Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20541-4912 U.S.A. Copyright (c) 2000 by the Library of Congress except within the USA. This publication may be reproduced without permission provided the source is fully acknowledged. This publication will be reissued from time to time as needed to incorporate revisions. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.v PART I: NAME SEQUENCE.11 PART II: CODE SEQUENCE.153 APPENDIX A: CHANGES.159 MARC Code List for Languages February 2000 page iii February 2000 MARC Code List for Languages ■ Introduction INTRODUCTION This document contains a list of languages and their associated three-character alphabetic codes. The purpose of this list is to allow the designation of the language or languages in MARC records. The list contains 434 discrete codes, of which 54 are used for groups of languages. -

Flags of Constructed Languages

Flags of Constructed Languages Patrice de La Condamine Abstract Since the dawn of humanity, humans have oscillated between the preservation of their own individuality and identity and their need to belong to a global community. The ideal of embracing and of researching the unification of its origins haunts their hearts. With this central to its spirit, constructed languages were developed, whether destined for secondary or international use, intended for vast cultural arenas or with strictly a philosophical use in mind. One will encounter well-known names such as Volapuk, Esperanto, Ido, Bolak, Interlingua, Occidental but also Glosa, Kotava, Lingua Franca Nova, and Atlango. Or even Folkspraat, Slovio, Norden, Afrihili, Slovianski, Hedsdel, etc. And we haven’t even mentioned the philosophical language Lojban. The most interesting aspect is establishing that all these languages have flags which translate the messages and the ideals of the groups in question. Interpreting the flags of constructed languages is essential for several reasons; firstly it allows us to understand that all these flags without exception, deliver the same message that the their existence isn’t necessarily linked to the simple notion of territory, and secondly, the flag is first and foremost, by means of its design and colours, a mental territory. After having shown and explained the different flags we will conclude with the presentation of the flag of Conlang, a language created by the United Nations of constructed languages. Folkspraak Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 159 FLAGS OF CONSTRUCTED LANGUAGES Introduction For everyone present here for this 24th International Congress of Vexillology in Washington, it is not necessary to explain the vital need that one has to represent oneself through the use of emblems, and we all know the essential place which flags occupy in this role. -

Behavioral Health Data System

Behavioral Health Data System Behavioral Health Supplemental Transaction Data Guide VERSION: 4.1 PUBLISH DATE: 7/16/2020 APPROVE DATE: 7/16/2020 GUIDE EFFECTIVE DATE: 1/1/2020 LAST UPDATED: 7/16/2020 Table of Contents Data Guide Overview: ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Terminology Guide ............................................................................................................................................................ 10 Document Use Guide ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Navigation ......................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Effective Dates .................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Nationally Accepted Health Information Technology (HIT) Code Crosswalk: .................................................................. 11 General Considerations of Guide ......................................................................................................................................... -

Abkhazian Achinese Acoli Adangme Adygei Adyghe Afar Afrihili

Abkhazian Achinese Acoli Adangme Adygei Adyghe Afar Afrihili Afrikaans Afro-Asiatic (Other) Akan Akkadian Albanian Aleut Algonquian languages Altaic (Other) Amharic Apache languages Arabic Aragonese Aramaic Arapaho Araucanian Arawak Armenian Artificial (Other) Assamese Asturian Athapascan languages Australian languages Austronesian (Other) Avaric Avestan Awadhi Aymara Azerbaijani Bable Balinese Baltic (Other) Baluchi Bambara Bamileke languages Banda Bantu (Other) Basa Bashkir Basque Batak (Indonesia) Beja Belarusian Bemba Bengali; ben Berber (Other) Bhojpuri Bihari Bikol Bilin Bini Bislama Blin Bokm/ Norwegian Bosnian Braj Breton Buginese Bulgarian Buriat Burmese Caddo Carib Castilian Catalan Caucasian (Other) Cebuano Celtic (Other) Central American Indian (Other) Chagatai Chamic languages Chamorro Chechen Cherokee Chewa Cheyenne Chibcha Chichewa Chinese Chinook jargon Chipewyan Choctaw Chuang Church Slavic Church Slavonic Chuukese Chuvash Classical Newari Coptic Cornish Corsican Cree Creek Creoles and pidgins (Other) Creoles and pidgins, English-based (Other) Creoles and pidgins, Frenchbased (Other) Creoles and pidgins, Portuguese-based (Other) Crimean Tatar Crimean Turkish Croatian Cushitic (Other) Czech Dakota Danish Dargwa Dayak Delaware Dinka Divehi Dogri Dogrib Dravidian (Other) Duala Dutch, Middle (ca. 1050-1350) Dutch/ Flemish Dyula Dzongkha Efik Egyptian (Ancient) Ekajuk Elamite English English, Middle (1100-1500) English, Old (ca.450-1100) Erzya Esperanto Estonian Ewe Ewondo Fang Fanti Faroese Fijian Filipino Finnish Finno-Ugrian