New Blood for Old Parties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Mann Im Schatten Seine Ämter Haben Inzwischen Andere, Seine Macht Haben Sie Nicht

Deutschland CDU Der Mann im Schatten Seine Ämter haben inzwischen andere, seine Macht haben sie nicht. Plant Wolfgang Schäuble ein Comeback? Von Tina Hildebrandt nichtsnutzige Zeitgenossen geisti- ge Überlegenheit spüren zu las- sen, haben seit jeher Distanz zwi- schen Schäuble und seiner Umge- bung geschaffen. Herrisch, kalt, fast unmensch- lich in seiner Kontrolliertheit fan- den und finden ihn viele. In der Fraktion, die er acht Jahre lang streng geführt hat, sowieso. Auch in seinem eigenen Landesverband Baden-Württemberg war Schäuble nie unumstritten. Seit seinem putschartigen Sturz vom Chefsessel der CDU ver- größert ein kollektives schlechtes Gewissen die Distanz. In der Frak- tion sitzt Schäuble hinten links bei seiner Landesgruppe, im Plenum des Bundestags in der zweiten Reihe. Ein Denkmal der Disziplin, das die so genannten Spitzenkräf- te in der ersten Reihe durch bloße Anwesenheit deklassiert und alle anderen daran erinnert, dass sie einen erfolgreichen Parteichef dem Rechtsbrecher Helmut Kohl STEFFEN SCHMIDT / AP SCHMIDT STEFFEN geopfert haben. CDU-Politiker Schäuble: „Ich beschäftige mich nicht mit Posten“ Schäuble weiß das alles. Er hat oft unter dieser Distanz gelitten. ie Hände senken sich auf das Ge- sagt, „können mich das überhaupt nicht Umso mehr genießt er die Wertschätzung, sicht wie ein Vorhang auf die Büh- fragen. Fragen können mich nur die Vor- die ihm nun von Parteifreunden wie dem Dne. Blaue Augen spähen belustigt sitzenden von CDU und CSU.“ sächsischen Premier Kurt Biedenkopf, dem zwischen den Fingern hervor, dann lässt Anderthalb Jahre ist es her, dass sie ihn Thüringer Bernhard Vogel oder dem CSU- Wolfgang Schäuble ein mildes Grinsen se- als Partei- und Fraktionschef verjagt ha- Mann Michael Glos entgegengebracht hen. -

Klausurtagungen U. Gäste CSU-Landesgr

Gäste der CSU-Landesgruppe - Klausurtagungen in Wildbad Kreuth und Kloster Seeon Kloster Seeon (II) 04.01. – 06.01.2018 Greg Clark (Britischer Minister für Wirtschaft, Energie und Industriestrategie) Vitali Klitschko (Bürgermeister von Kiew und Vorsitzender der Regierungspartei „Block Poroshenko“) Frank Thelen (Gründer und Geschäftsführer von Freigeist Capital) Dr. Mathias Döpfner (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Axel Springer SE und Präsident des Bundesverbandes Deutscher Zeitungsverleger) Michael Kretschmer (Ministerpräsident des Freistaates Sachsen) Kloster Seeon (I) 04.01. – 06.01.2017 Erna Solberg (Ministerpräsidentin von Norwegen und Vorsitzende der konservativen Partei Høyre) Julian King (EU-Kommissar für die Sicherheitsunion) Fabrice Leggeri (Exekutive Direktor EU-Grenzschutzagentur FRONTEX) Dr. Bruno Kahl (Präsident des Bundesnachrichtendienstes) Prof. Dr. Heinrich Bedford-Strohm (Landesbischof von Bayern und Vorsitzender des Rates der EKD) Prof. Dr. Norbert Lammert MdB (Präsident des Deutschen Bundestages) Joe Kaeser (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Siemens AG) Wildbad Kreuth XL 06.01. – 08.01.2016 Dr. Angela Merkel MdB David Cameron ( Premierminister des Vereinigten Königreichs) Prof. Peter Neumann ( Politikwissenschaftler) Guido Wolf MdL (Vorsitzender der CDU-Fraktion im Landtag von Baden-Württemberg) Dr. Frank-Jürgen Weise (Vorstandsvorsitzender der Bundesagentur für Arbeit und Leiter des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge) Wildbad Kreuth XXXIX 07.01. – 09.01.2015 Professor Dr. Vittorio Hösl * Günther Oettinger (EU-Kommissar für Digitale Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft) Jens Stoltenberg (Nato-Generalsekretär) Margret Suckale (Präsidentin des Chemiearbeitgeberverbandes) Hans Peter Wollseifer (Präsident des Zentralverbandes des Deutschen Handwerks) Dr. Thomas de Maizière (Bundesminister des Innern) Pawlo Anatolijowytsch Klimkin (Außenminister der Ukraine) Wildbad Kreuth XXXVIII 07.01. – 09.01.2014 Matthias Horx (Gründer und Inhaber des Zukunftsinstituts Horx GmbH, Wien) * S.E. John B. -

Aufs Arbeitsamt“

DEUTSCHLAND A. MELDE / CONTRAST PRESS MELDE PRESS Ostdeutscher Minister Ortleb (Januar 1994), ostdeutsche Ministerin Merkel: „Wir können viele Dinge allein“ Die Bürgerrechtler Angelika Barbe Abgeordnete (SPD), Stephan Hilsberg (SPD) oder Wolfgang Ullmann (Bündnis 90) fielen in Bundestagsdebatten und -gremien durchaus auf, blieben aber Solisten. Aufs Uwe Lühr, der 1990 als einziger Li- beraler ein Direktmandat in Halle ge- wonnen hatte, mußte als FDP-Gene- Arbeitsamt ralsekretär abdanken, weil Klaus Kin- kel Parteichef wurde: „Der Kinkel Der Frust ist groß, doch die mei- brauchte keinen mehr, der sich um die sten ostdeutschen Parlamentarier Ost-West-Integration kümmert.“ Daß sie Ostdeutsche seien, mit anderen Er- wollen wieder in den Bundestag. fahrungen und Biographien, meint Rolf Schwanitz (SPD), „hielten wir für ie Debatte über seinen Kanzler- die Geschäftsgrundlage“. Zu spät sei Etat Anfang September war in ihnen klargeworden, übt Uwe Küster Dvollem Gang, als Helmut Kohl (SPD) Selbstkritik, „daß es nicht nur einfiel, daß sich jetzt eine Ostdeutsche reicht, fleißig am Schreibtisch zu sit- am Rednerpult des Bundestages gut zen“. machen würde. Wo denn die Angela DARCHINGER Anfangs fanden die Ostdeutschen in Merkel sei, herrschte er seinen Staats- Ostabgeordnete Enkelmann ihren Parteien sogar Gehör. Die SPD minister Anton Pfeifer an. Kleiner Triumph legte fest, daß in jede Arbeitsgruppe Die einzige ostdeutsche Frau in der Fraktion einer der 35 Ostgenossen Kohls Kabinett war in ihrem Dienstwa- Udo Haschke, riß es von den Sitzen delegiert werden sollte. Schwanitz saß gen auf dem Weg zu einem Interview hoch: „Genau, genau“, rief der anson- nicht nur der Fraktionsgruppe „Deut- beim Norddeutschen Rundfunk. Über sten stille Mann, der für den nächsten sche Einheit“ vor, er mußte in zehn Autotelefon erreichte Pfeifer die plötz- Bundestag nicht mehr kandidiert, anderen Kommissionen, Ausschüssen lich Begehrte. -

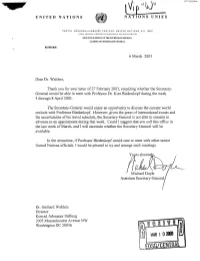

EOSG/CENTEB Note to Mr

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS ADRESSE POSTAL E: UNITED NATIONS. N. Y 10017 CABLE ADDRESS ADRESSE T E L EG R A P III Q LFE: UNATIONS KEWVOHK EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL CABINET DU SECRETAIRE GENERAL DEFERENCE 6 March 2003 Dear Dr. Wahlers, Thank you for your letter of 27 February 2003, enquiring whether the Secretary- General would be able to meet with Professor Dr. Kurt Biedenkopf during the week 4 through 8 April 2003. The Secretary-General would enjoy an opportunity to discuss the current world outlook with Professor Biedenkopf. However, given the press of international events and the uncertainties of his travel schedule, the Secretary-General is not able to commit in advance to an appointment during that week. Could I suggest that you call this office in the last week of March, and I will ascertain whether the Secretary-General will be available. In the meantime, if Professor Biedenkopf would care to meet with other senior United Nations officials, I would be pleased to try and arrange such meetings. Yours sincer Michael Doyle Assistant Secretary-General Dr. Gerhard Wahlers Director Konrad Adenauer Stiftung 2005 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington DC 20036 EOSG/CENTEB Note to Mr. Riza Visit of Professor Dr. Kurt Biedenkopf I hesitate to recommend anything additional for the SG's schedule, given the press of events now and the likelihood that the same pressure will exist in early April. Nonetheless, the SG might find a conversation with this eminent scholar/official interesting and useful. Biedenkopf s knowledge of trans-Atlantic relations is profound. -

Vernichten Oder Offenlegen? Zur Entstehung Des Stasi-Unterlagen-Gesetzes

Silke Schumann Vernichten oder Offenlegen? Zur Entstehung des Stasi-Unterlagen-Gesetzes Eine Dokumentation der öffentlichen Debatte 1990/1991 Reihe A: Dokumente Nr. 1/1995 Der Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik Abteilung Bildung und Forschung 10106 Berlin E-Mail: [email protected] Die Meinungen, die in dieser Schriftenreihe geäußert werden, geben ausschließlich die Auffassungen der Autoren wieder. Abdruck und publizistische Nutzung sind nur mit Angabe des Verfassers und der Quelle sowie unter Beachtung des Urheberrechtsgesetzes gestattet. Schutzgebühr: 5,00 € Nachdruck der um ein Vorwort erweiterten 2. Auflage von 1997 Berlin 2020 ISBN 978-3-942130-39-4 Eine PDF-Version dieser Publikation ist unter der folgenden URN kostenlos abrufbar: urn:nbn:de:0292-97839421303940 Vorwort zur Neuauflage Im Vergleich mit den politischen Umbrüchen in den anderen postkommunistischen Ländern war die Friedliche Revolution 1989/90 in der DDR außerordentlich stark von der Auflösung der Stasi und der Auseinandersetzung um die Vernichtung ihrer Akten geprägt. Die Besetzung der regionalen Dienststellen im Dezember 1989 und der Zentrale des MfS (Ministerium für Staats- sicherheit) am 15. Januar 1990 bildeten Höhepunkte des revolutionären Geschehens. Die Fokus- sierung der Bürgerbewegung auf die Entmachtung des geheimpolizeilichen Apparats und die Sicherung seiner Hinterlassenschaft ist unübersehbar. Diese Fokussierung findet gleichsam ihre Fortsetzung in der Aufarbeitung der diktatorischen Vergangenheit der DDR in den darauffol- genden Jahren, in denen wiederum das Stasi-Thema und die Nutzung der MfS-Unterlagen im Vordergrund standen. Das könnte im Rückblick als zwangsläufige Entwicklung erscheinen, doch bei näherer Betrach- tung wird deutlich, dass das nicht der Fall war. Die Diskussionen des Jahres 1990 zeigen, dass die Nutzung von Stasi-Unterlagen für die Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit selbst in Kreisen der Bürgerbewegung keineswegs unumstritten war. -

Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 1-2011 Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006 Melanie Kintz Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Kintz, Melanie, "Recruitment to Leadership Positions in the German Bundestag, 1994-2006" (2011). Dissertations. 428. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/428 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECRUITMENT TO LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, 1994-2006 by Melanie Kintz A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science Advisor: Emily Hauptmann, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2011 RECRUITMENT TO LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, 1994-2006 Melanie Kintz, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation looks at the recruitment patterns to leadership positions in the German Bundestag from 1994 to 2006 with the objective of enhancing understanding of legislative careers and representation theory. Most research on political careers thus far has focused on who is elected to parliament, rather than on which legislators attain leadership positions. However, leadership positions within the parliament often come with special privileges and can serve as stepping stones to higher positions on the executive level. -

19. Oktober 1981: Sitzung Der Landesgruppe

CSU-LG – 9. WP Landesgruppensitzung: 19. 10. 1981 19. Oktober 1981: Sitzung der Landesgruppe ACSP, LG 1981: 15. Überschrift: »Protokoll der 18. Landesgruppensitzung am 19. Oktober 1981«. Zeit: 20.00–20.20 Uhr. Vorsitz: Zimmermann. Anwesend: Althammer, Biehle, Bötsch, Faltlhauser, Fellner, Geiger, Glos, Handlos, Hartmann, Höffkes, Höpfinger, Graf Huyn, Keller, Kiechle, Klein, Kraus, Kunz, Lemmrich, Linsmeier, Niegel, Probst, Regenspurger, Röhner, Rose, Rossmanith, Sauter, Spilker, Spranger, Stücklen, Voss, Warnke, Zierer, Zimmermann. Sitzungsverlauf: A. Bericht des Landesgruppenvorsitzenden Zimmermann über die Bonner Friedensdemonstration vom 10. Oktober 1981, die Haushaltslage, den Deutschlandtag der Jungen Union in Köln, die USA-Reise des CDU-Parteivorsitzenden Kohl und die Herzerkrankung des Bundeskanzlers. B. Erläuterungen des Parlamentarischen Geschäftsführers Röhner zum Plenum der Woche. C. Allgemeine Aussprache. D. Erläuterungen zu dem Gesetzentwurf der CDU/CSU-Fraktion zum Schutze friedfertiger Demonstrationen und Versammlungen. E. Vorbereitung der zweiten und dritten Beratung des von der Bundesregierung eingebrachten Gesetzentwurfs über die Anpassung der Renten der gesetzlichen Rentenversicherung im Jahr 1982 und der zweiten und dritten Beratung des Entwurfs eines Elften Gesetzes über die Anpassung der Leistungen des Bundesversorgungsgesetzes (Elftes Anpassungsgesetz-KOV). [A.] TOP 1: Bericht des Vorsitzenden Dr. Zimmermann begrüßt die Landesgruppe. Er gratuliert den Kollegen Dr. Dollinger, Keller und Hartmann zu ihren Geburtstagen. Dr. Zimmermann betont, daß sich selten die politische Lage in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland zwischen zwei Landesgruppensitzungen so verändert habe: Friedensdemonstration1, Haushaltslage und Gesundheit des Kanzlers.2 Drei grundverschiedene Bereiche, von denen jeder allein auf die Koalition destabilisierende Wirkung habe. Was die Haushaltslage angehe, so bedeute eine Lücke von 5 bis 7 Mrd. DM, wie Matthöfer sie für den Haushalt 1982 zugebe, das Ende des vorliegenden Entwurfs.3 1 Zur Friedensdemonstration in Bonn am 10. -

Deutscher Bundestag — 12

Plenarprotokoll 12/76 Deutscher Stenographischer Bericht 76. Sitzung Bonn, Donnerstag, den 13. Februar 1992 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Vorsitzenden des Obersten (Steueränderungsgesetz 1992) (Drucksa- Rates der Republik Litauen und seiner Dele- chen 12/1108, 12/1368, 12/1466, 12 /1506, gation 6273 A 12/1691, 12/2044) b) Beratung der Beschlußempfehlung des Glückwünsche zu den Geburtstagen der Ausschusses nach Artikel 77 des Grund- Abgeordneten Erika Reinhardt und Dr. gesetzes (Vermittlungsausschuß) zu dem Horst Ehmke 6273B Gesetz zur Aufhebung des Struktur- hilfegesetzes und zur Aufstockung des Namensänderung eines Ausschusses . 6273 B Fonds „Deutsche Einheit" (Drucksachen 12/1227, 12/1374, 12/1494, 12/1692, Nachträgliche Überweisung des 13. Subven- 12/2045) tionsberichts der Bundesregierung an den Hans H. Gattermann FDP . 6274 C Ausschuß für Forschung, Technologie und Technikfolgenabschätzung 6273 B Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble CDU/CSU . 6276A Dr. Peter Struck SPD 6278B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- nung 6273C Dr. Hermann Otto Solms FDP . 6280 C Dr. Barbara Höll PDS/Linke Liste . 6282 A Tagesordnungspunkt 3: Nachwahl eines Mitglieds der Parlamen- Werner Schulz (Berlin) Bündnis 90/GRÜNE 6282 D tarischen Kontrollkommission: Wahlvor- Gerhard Schröder, Ministerpräsident des schlag der Fraktion der CDU/CSU Landes Niedersachsen 6283 C (Drucksache 12/2034) 6273 D Dr. Theodor Waigel, Bundesminister BMF 6285 C Ergebnis der Wahl . 6287 D Namentliche Abstimmung 6287 D Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 2: Beratung des Antrags der Fraktion der Ergebnis -

Angelika Barbe SPD � 2373 C Dr

Plenarprotokoll 12/31 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 31. Sitzung Bonn, Donnerstag, den 13. Juni 1991 Inhalt: Verzicht der Abg. Dr. Rose Götte und Flo- Gebiet des Gesellschaftsrechts be- rian Gerster (Worms) auf die Mitgliedschaft treffend Gesellschaften mit be- im Deutschen Bundestag 2357 A schränkter Haftung mit einem ein- zigen Gesellschafter (Drucksache 12/625) Eintritt der Abg. Peter Büchner (Speyer) und Ralf Walter (Cochem) in den Deutschen Bun- destag 2357 A d) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesre- gierung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zu der Vereinbarung vom Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- 21. Dezember 1989 über Gemein- nung 2357 B schaftspatente und zu dem Protokoll vom 21. Dezember 1989 über eine et- waige Änderung der Bedingungen für Absetzung eines Punktes von der Tagesord- das Inkrafttreten der Vereinbarung nung 2357 C über Gemeinschaftspatente sowie zur Änderung patentrechtlicher Vor- schriften Tagesordnungspunkt 4: (Zweites Gesetz über das Gemeinschaftspatent) (Drucksache Überweisungen im vereinfachten Ver- 12/632) fahren a) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesre- e) Erste Beratung des von den Abgeord- gierung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines neten Hermann Wimmer (Neuötting), Gesetzes zu dem Abkommen vom Brigitte Adler, Horst Kubatschka, wei- 23. Dezember 1988 zwischen der Bun- teren Abgeordneten und der Fraktion desrepublik Deutschland und der der SPD eingebrachten Entwurfs ei- Republik Österreich über die gegen- nes Zweiten Gesetzes zur Änderung seitige Hilfeleistung bei Katastro- des Forstschäden-Ausgleichsgesetzes -

Liste Deutscher Teilnehmer Bilderberg

• Egon Bahr (1968, 1971, 1982, 1987), German Minister, creator of the Ostpolitik • Rainer Barzel (1966), former German opposition leader • Kurt Biedenkopf (1992), former Prime Minister of Saxony • Max Brauer (1954, 1955, 1958, 1963, 1964, 1966), former Mayor of Hamburg • Birgit Breuel (1973, 1979, 1980, 1991, 1992, 1994), chairwoman of Treuhandanstalt • Andreas von Bülow (1978), former Minister of Research of Germany • Karl Carstens (1971), former President of Germany • Klaus von Dohnanyi (1975, 1977), former Mayor of Hamburg • Ursula Engelen-Kefer (1998), former chairwoman of the German Confederation of Trade Unions • Björn Engholm (1991), former Prime Minister of Schleswig-Holstein • Ludwig Erhard (1966), former Chancellor of Germany • Fritz Erler (1955, 1957, 1958, 1963, 1964, 1966), Socialist Member of Parliament • Joschka Fischer (2008), former Minister of Foreign Affairs (Germany) • Herbert Giersch (1975), Director, Institut fur Weltwirtschaft an der Universitat Kiel • Helmut Haussmann (1979, 1980, 1990, 1996), former Minister of Economics of Germany • Wolfgang Ischinger (1998, 2002, 2008), former German Ambassador to Washington • Helmut Kohl (1980, 1982, 1988), former Chancellor of Germany • Walter Leisler Kiep (1974, 1975, 1977, 1980), former Treasurer of the Christian Democratic Union (Germany) • Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1955, 1957, 1966), former Chancellor of Germany • Hans Klein (1986), Member of German Bundestag • Otto Graf Lambsdorff (1980, 1983, 1984), former Minister of Economics of Germany • Karl Lamers (1995), Member of the -

2008 T R O Ep R 2008 N A

of the 18th century, Rüstkammer of the 18thcentury, 1st half Tatar, or Ottoman Saddle, comes comes of the orient The fascination Cammer“ “Türckische the 2009–OpeningofDecember to to the Residenzschloss STaaTliChe Kunstsammlungen Dresden · annual repOrT 2008 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Albertinum Zwinger with Semperbau Wasserpalais, Schloss Pillnitz Page 4 International Special ExhibiTions Foreword PARTNERshiPs Page 27 Page 17 Special exhibitions in Dresden China iN Dresden Message of greeting from the and Saxony in 2008 iN ChiNA Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs Page 34 Page 18 Special exhibitions abroad in 2008 Page 9 The Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Cultural exchange past and future – Dresden in international dialogue a year of encounters between Dresden WiTh kind support and Beijing Page 24 Trip to Russia Launch event with Helmut Schmidt Page 37 and Kurt Biedenkopf Page 25 In your mid-20s? Off to the museum! Visit to Warsaw Page 10 Page 38 Seven exhibitions and a Societies of friends wide-ranging programme of events Page 38 Page 13 Sponsors and donors in 2008 A chance to work abroad Page 40 Page 14 Partners from the business world China in Dresden Page 15 Dresden in China Residenzschloss Jägerhof Lipsiusbau on the Brühlsche Terrasse From ThE collections Visitors Museum bUildiNgs Page 43 Page 63 Page 75 Selected purchases and donations A host must be prepared – improving Two topping-out ceremonies and our Visitor Service will remain a surprising find mark the progress Page 47 an important task in the future of building work at the museums -

60 Jahre CDU. Verantwortung Für Deutschland Und Europa

60 JAHRE CDU VERANTWORTUNG FÜR DEUTSCHLAND UND EUROPA Ansprechpartner: Dr. Günter Buchstab Leiter Hauptabteilung Wissenschaftliche Dienste/ Archiv für Christlich-Demokratische Politik Rathausallee 12 53757 Sankt Augustin Tel: 02241-246210 Fax: 02241-246669 E-Mail: [email protected] LEITFADEN „60 JAHRE CDU“ INHALT ¾ GESCHICHTE DER CDU .......................................................................3 ¾ VORSITZENDE UND GENERALSEKRETÄRE ................................................. 10 ¾ KÖLNER LEITSÄTZE .......................................................................... 12 ¾ GRÜNDUNGSAUFRUF BERLIN ............................................................... 16 LEITFADEN „60 JAHRE CDU“ 2 GESCHICHTE DER CDU Die Gründung der Unionsparteien ist die bedeutsamste Innovation in der deutschen Parteiengeschichte seit 1945. CDU und CSU haben die seitherige Entwicklung we- sentlich mitbestimmt und dem Parteiensystem zu einer ungewohnten Stabilität ver- holfen. Dieser Neuanfang bedeutete zugleich das Ende eines christlich-konfessionel- len Parteityps, der sich seit der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts entwickelt hatte. Unmittelbar nach dem Zusammenbruch des NS-Regimes entstanden überall in Deutschland politische Gruppierungen, die eine interkonfessionelle Volkspartei an- strebten. Am 26.6.1945 veröffentlichte in Berlin ein Gründerkreis mit Andreas Her- mes an der Spitze einen Aufruf zur Sammlung christlich, demokratischer und sozialer Kräfte. In Köln fiel im Juli 1945 mit dem Aufruf für die Gründer einer Christlich- Demokratischen