Biomass and Climate Neutrality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for Biofuels Alongside the EU-ETS

The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS Stefan Boeters, Paul Veenendaal, Nico van Leeuwen and Hugo Rojas-Romagoza CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis Paper for presentation at the Eleventh Annual GTAP Conference ‘Future of Global Economy’, Helsinki, June 12-14, 2008 1 Table of contents Summary 3 1 The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Climate policy baseline 7 1.3 Promoting the use of biofuels 10 1.4 Increasing transport fuel excises as a policy alternative from the CO 2-emission reduction point of view 22 1.5 Conclusions 23 Appendix A: Characteristics of the WorldScan model and of the baseline scenario 25 A.1 WorldScan 25 A.2 Background scenario 27 A.3 Details of biofuel modelling 28 A.4 Sensitivity analysis with respect to land allocation 35 References 38 2 Summary The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS On its March 2007 summit the European Council agreed to embark on an ambitious policy for energy and climate change that establishes several targets for the year 2020. Amongst others this policy aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20% compared to 1990 and to ensure that 20% of total energy use comes from renewable sources, partly by increasing the share of biofuels up to at least 10% of total fuel use in transportation. In meeting the 20% reduction ceiling for greenhouse gas emissions the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) will play a central role as the ‘pricing engine’ for CO 2-emissions. The higher the emissions price will be, the sooner technological emission reduction options will tend to be commercially adopted. -

Scheme Principles for the Production of Biomass, Biofuels and Bioliquids

REDcert Scheme principles for the production of biomass, biofuels and bioliquids Version 05 Scheme principles for the production of biomass, bioliquids and biofuels 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................. 4 2 Scope of application .................................................................................................... 4 3 Definitions .................................................................................................................... 6 4 Requirements for sustainable biomass production .................................................. 9 4.1 Land with high biodiversity value (Article 17 (3) of Directive 2009/28/EC) .............. 9 4.1.1 Primary forest and other wooded land ............................................................ 9 4.1.2 Areas designated by law or by the relevant competent authority for nature protection purposes ......................................................................................................10 4.1.3 Areas designated for the protection of rare, threatened or endangered ecosystems or species .................................................................................................11 4.1.4 Highly biodiverse grassland ...........................................................................11 4.2 Land with high above-ground or underground carbon stock (Article 17 (4) of Directive 2009/28/EC) ..........................................................................................................15 -

Sustainability Criteria for Biofuels Specified Brussels, 13 March 2019 1

European Commission - Fact Sheet Sustainability criteria for biofuels specified Brussels, 13 March 2019 1. What has the Commission adopted today? As foreseen by the recast Renewable Energy Directive adopted by the European Parliament and Council, which has already entered into force, the Commission has adopted today a delegated act setting out the criteria for determining high ILUC-risk feedstock for biofuels (biofuels for which a significant expansion of the production area into land with high-carbon stock is observed) and the criteria for certifying low indirect land-use change (ILUC)–risk biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels. An Annex to the act demonstrating the expansion of the production area of different kinds of crops has also been adopted. 2. What are biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels? Biofuels are liquid fuels made from biomass and consumed in transport. The most important biofuels today are bioethanol (made from sugar and cereal crops) used to replace petrol, and biodiesel (made mainly from vegetable oils) used to replace diesel. Bioliquids are liquid fuels made from biomass and used to produce electricity, heating or cooling. Biomass fuels are solid or gaseous fuels made from biomass. Therefore, all these fuels are made from biomass. They have different names depending on their physical nature (solid, gaseous or liquid) and their use (in transport or to produce electricity, heating or cooling). 3. What is indirect land use change (ILUC)? ILUC can occur when pasture or agricultural land previously destined for food and feed markets is diverted to biofuel production. In this case, food and feed demand still needs to be satisfied, which may lead to the extension of agriculture land into areas with high carbon stock such as forests, wetlands and peatlands. -

Scheme Principles for GHG Calculation

Scheme principles for GHG calculation Version EU 05 Scheme principles for GHG calculation © REDcert GmbH 2021 This document is publicly accessible at: www.redcert.org. Our documents are protected by copyright and may not be modified. Nor may our documents or parts thereof be reproduced or copied without our consent. Document title: „Scheme principles for GHG calculation” Version: EU 05 Datum: 18.06.2021 © REDcert GmbH 2 Scheme principles for GHG calculation Contents 1 Requirements for greenhouse gas saving .................................................... 5 2 Scheme principles for the greenhouse gas calculation ................................. 5 2.1 Methodology for greenhouse gas calculation ................................................... 5 2.2 Calculation using default values ..................................................................... 8 2.3 Calculation using actual values ...................................................................... 9 2.4 Calculation using disaggregated default values ...............................................12 3 Requirements for calculating GHG emissions based on actual values ........ 13 3.1 Requirements for calculating greenhouse gas emissions from the production of raw material (eec) .......................................................................................13 3.2 Requirements for calculating greenhouse gas emissions resulting from land-use change (el) ................................................................................................17 3.3 Requirements for -

Environmental Justice: EU Biofuel Demand and Oil Palm Cultivation in Malaysia

Lund Conference on Earth System Governance 2012 Environmental justice: EU biofuel demand and oil palm cultivation in Malaysia Erika M. Machacek Conference Paper Lund, Sweden, March 2012 "As a metaphorical image, friction reminds us that heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power" (Tsing, 2005) Table of Contents ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................... VIII 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PROBLEM DEFINITION ................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 METHOD ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 LIMITATION AND SCOPE .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.5 AUDIENCE ................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.6 DISPOSITION ............................................................................................................................................... -

Paving the Way to Carbon-Neutral Transport: 10-Point Plan To

Paving the way to carbon-neutral transport 10-point plan to help implement the European Green Deal January 2020 CONTEXT The transport sector is responsible for 22.3% of total EU greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with road transport representing 21.1% of total emissions. Breaking this down further, passenger cars account for 12.8% of Europe’s emissions, vans for 2.5%, while heavy-duty trucks and buses are responsible for 5.6%. Transport is therefore a key focus and driver for climate protection measures. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) strongly believes that carbon-neutral road transport is possible by 2050. This however will represent a seismic shift, requiring a holistic approach with increasing efforts from all stakeholders. * All CO2 equivalent ** Industry = ‘Manufacturing industries and construction’ + ‘Industrial processes and product use’ Source: European Environment Agency (EEA) AUTO INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTION Investing €57.4 billion in R&D annually, the automotive sector is Europe's largest private contributor to innovation, accounting for 28% of total EU spending. Much of this investment is dedicated to clean mobility solutions. The automobile industry embraces the Paris Agreement and its goals. Manufacturers also support the climate protection initiatives of the European Commission, such as the ‘Clean Planet for All’ strategy, provided all stakeholders contribute their share and the achievements to date are taken into account. ACEA’s 10-point plan to help implement the European Green Deal – January 2020 1 ACEA members are fully committed to deliver the ambitious 025 and 030 C2 reduction targets. In order to provide legal certainty for the industry as it moves towards carbon neutrality in 050, the 2022/2023 timeline for the revies of the regulations should be adhered to (as as endorsed by the European Council in December 201). -

Bioenergy's Role in Balancing the Electricity Grid and Providing Storage Options – an EU Perspective

Bioenergy's role in balancing the electricity grid and providing storage options – an EU perspective Front cover information panel IEA Bioenergy: Task 41P6: 2017: 01 Bioenergy's role in balancing the electricity grid and providing storage options – an EU perspective Antti Arasto, David Chiaramonti, Juha Kiviluoma, Eric van den Heuvel, Lars Waldheim, Kyriakos Maniatis, Kai Sipilä Copyright © 2017 IEA Bioenergy. All rights Reserved Published by IEA Bioenergy IEA Bioenergy, also known as the Technology Collaboration Programme (TCP) for a Programme of Research, Development and Demonstration on Bioenergy, functions within a Framework created by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Views, findings and publications of IEA Bioenergy do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the IEA Secretariat or of its individual Member countries. Foreword The global energy supply system is currently in transition from one that relies on polluting and depleting inputs to a system that relies on non-polluting and non-depleting inputs that are dominantly abundant and intermittent. Optimising the stability and cost-effectiveness of such a future system requires seamless integration and control of various energy inputs. The role of energy supply management is therefore expected to increase in the future to ensure that customers will continue to receive the desired quality of energy at the required time. The COP21 Paris Agreement gives momentum to renewables. The IPCC has reported that with current GHG emissions it will take 5 years before the carbon budget is used for +1,5C and 20 years for +2C. The IEA has recently published the Medium- Term Renewable Energy Market Report 2016, launched on 25.10.2016 in Singapore. -

Sustainable Use of Biomass Feedstock – Global and Regional

SESSION I: Forest Biomass resources for biochar production 1st FOREBIOM Sustainable Use of Biomass Workshop Feedstock Potentials of Biochar to – Global and Regional Aspects– mitigate climate change Florian Kraxner Georg Kindermann, Sylvain Leduc, Stefan Frank, Petr th th Havlík, Eva-Maria Nordström, Hannes Böttcher, Michael 4 -5 April, 2013 Obersteiner and IIASA‘s ESM Team Austrian Academy of Sciences Ecosystems Services and Management (ESM) Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) THE STATUS-QUO GLOBAL PROJECTIONS – POTENTIALS AND SOURCES EXAMPLE: BIOMASS FOR BIOENERGY Post 2012 Carbon Management Global Future Energy Portfolios, 2000 – 2100 Source: modified after Obersteiner et al., 2007 Cumulative biomass production (EJ/grid) for bioenergy between 2000 and 2100 at the energy price supplied by MESSAGE based on the revised IPCC SRES A2r scenario (country investment risk excluded). Source: Rokityanskiy et al. 2006 p ( ) Source: IIASA, G4M (2008) Forest Management Certification (Potentials) Certified area relative to managed forest area by countries Kraxner et al., 2008 Source: compiled from FAO 2005, 2001; CIESIN 2007, ATFS 2008; FSC 2008; PEFC 2008. GLOBIOM Global Biosphere Management Model www.globiom.org Exogenous drivers Demand Population growth, economic growth Wood products Food Bioenergy PROCESS OPTIMIZATIO 50 regions Primary wood Crops Partial equilibriumN model SUPPLY products Max. CSPS PX5 ) 5 7 . 120 0 soto pred W B g 100 l and m pred k / RUMINANT G4M g ( EPIC shem pred s e k 80 kaitho pred a t n -

Benefits of Emissions Trading

BENEFITS OF EMISSIONS TRADING E M I S S I O N S T R A D I N G A C H I E V E S T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L O B J E C T I V E – R E D U C E D E M I S S I O N S – A T T H E L O W E S T C O S T Cap and trade is designed to deliver an environmental outcome; the cap must be met, or there are sanctions such as fines. Allowing trading within that cap is the most effective way of minimising the cost – which is good for business and good for households. Determining physical actions that companies must take, with no flexibility, is not guaranteed to achieve the necessary reductions. Nor is establishing a regulated price, since the price required to drive reductions may take policy-makers several years to determine. Cap and trade also provides a way of establishing rigour around emissions monitoring, reporting and verification – essential for any climate policy to preserve integrity. E M I S S I O N S T R A D I N G I S B E T T E R A B L E T O R E S P O N D T O E C O N O M I C F L U C T U A T I O N S T H A N O T H E R P O L I C Y T O O L S Allowing the open market to set the price of carbon translates to better flexibility and avoids price shocks or undue burdens. -

Bioliquids and Their Use in Power Generation €

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 129 (2020) 109930 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/rser Bioliquids and their use in power generation – A technology review T. Seljak a, M. Buffi b,c, A. Valera-Medina d, C.T. Chong e, D. Chiaramonti f, T. Katra�snik a,* a University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, A�sker�ceva Cesta 6, 1000, Ljubljana, Slovenia b RE-CORD, Viale Kennedy 182, 50038, Scarperia e San Piero, Italy c University of Florence, Industrial Engineering Department, Viale Morgagni 40, 50134, Firenze, Italy d Cardiff University College of Physical Sciences and Engineering, CF234AA, Cardiff, UK e China-UK Low Carbon College, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Lingang, Shanghai, 201306, China f University of Turin, Department of Energy "Galileo Ferraris", Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129, Torino, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The first EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) served as an effective push for world-wide research efforts on Bioliquids biofuels and bioliquids, i.e. liquid fuels for energy purposes other than for transport, including electricity, Micro gas turbine heating, and cooling, which are produced from biomass. In December 2018 the new RED II was published in the Internal combustion engine OfficialJournal of the European Union. Therefore, it is now the right time to provide a comprehensive overview Power generation of achievements and practices that were developed within the current perspective. To comply with this objective, Renewable energy directive Biofuels the present study focuses on a comprehensive and systematic technical evaluation of all key aspects of the different distributed energy generation pathways using bioliquids in reciprocating engines and micro gas tur bines that were overseen by these EU actions. -

Analytical Environmental Agency 2 21St Century Frontiers 3 22 Four 4

# Official Name of Organization Name of Organization in English 1 "Greenwomen" Analytical Environmental Agency 2 21st Century Frontiers 3 22 Four 4 350 Vermont 5 350.org 6 A Seed Japan Acao Voluntaria de Atitude dos Movimentos por Voluntary Action O Attitude of Social 7 Transparencia Social Movements for Transparency Acción para la Promoción de Ambientes Libres Promoting Action for Smokefree 8 de Tabaco Environments Ações para Preservação dos Recursos Naturais e 9 Desenvolvimento Economico Racional - APRENDER 10 ACT Alliance - Action by Churches Together 11 Action on Armed Violence Action on Disability and Development, 12 Bangladesh Actions communautaires pour le développement COMMUNITY ACTIONS FOR 13 integral INTEGRAL DEVELOPMENT 14 Actions Vitales pour le Développement durable Vital Actions for Sustainable Development Advocates coalition for Development and 15 Environment 16 Africa Youth for Peace and Development 17 African Development and Advocacy Centre African Network for Policy Research and 18 Advocacy for Sustainability 19 African Women's Alliance, Inc. Afrique Internationale pour le Developpement et 20 l'Environnement au 21è Siècle 21 Agência Brasileira de Gerenciamento Costeiro Brazilian Coastal Management Agency 22 Agrisud International 23 Ainu association of Hokkaido 24 Air Transport Action Group 25 Aldeota Global Aldeota Global - (Global "small village") 26 Aleanca Ekologjike Europiane Rinore Ecological European Youth Alliance Alianza de Mujeres Indigenas de Centroamerica y 27 Mexico 28 Alianza ONG NGO Alliance ALL INDIA HUMAN -

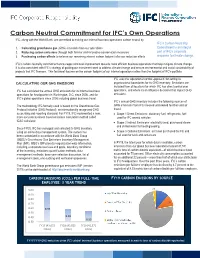

IFC Carbon Neutrality Committment Factsheet

Carbon Neutral Commitment for IFC’s Own Operations IFC, along with the World Bank, are committed to making our internal business operations carbon neutral by: IFC’s Carbon Neutrality 1. Calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from our operations Commitment is an integral 2. Reducing carbon emissions through both familiar and innovative conservation measures part of IFC's corporate 3. Purchasing carbon offsets to balance our remaining internal carbon footprint after our reduction efforts response to climate change. IFC’s carbon neutrality commitment encourages continual improvement towards more efficient business operations that help mitigate climate change. It is also consistent with IFC’s strategy of guiding our investment work to address climate change and ensure environmental and social sustainability of projects that IFC finances. This factsheet focuses on the carbon footprint of our internal operations rather than the footprint of IFC’s portfolio. IFC uses the ‘operational control approach’ for setting its CALCULATING OUR GHG EMISSIONS organizational boundaries for its GHG inventory. Emissions are included from all locations for which IFC has direct control over IFC has calculated the annual GHG emissions for its internal business operations, and where it can influence decisions that impact GHG operations for headquarters in Washington, D.C. since 2006, and for emissions. IFC’s global operations since 2008 including global business travel. IFC’s annual GHG inventory includes the following sources of The methodology IFC formally used is based on the Greenhouse Gas GHG emissions from IFC’s leased and owned facilities and air Protocol Initiative (GHG Protocol), an internationally recognized GHG travel: accounting and reporting standard.