Carbon Cycling, Privatization and the Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for Biofuels Alongside the EU-ETS

The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS Stefan Boeters, Paul Veenendaal, Nico van Leeuwen and Hugo Rojas-Romagoza CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis Paper for presentation at the Eleventh Annual GTAP Conference ‘Future of Global Economy’, Helsinki, June 12-14, 2008 1 Table of contents Summary 3 1 The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Climate policy baseline 7 1.3 Promoting the use of biofuels 10 1.4 Increasing transport fuel excises as a policy alternative from the CO 2-emission reduction point of view 22 1.5 Conclusions 23 Appendix A: Characteristics of the WorldScan model and of the baseline scenario 25 A.1 WorldScan 25 A.2 Background scenario 27 A.3 Details of biofuel modelling 28 A.4 Sensitivity analysis with respect to land allocation 35 References 38 2 Summary The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS On its March 2007 summit the European Council agreed to embark on an ambitious policy for energy and climate change that establishes several targets for the year 2020. Amongst others this policy aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20% compared to 1990 and to ensure that 20% of total energy use comes from renewable sources, partly by increasing the share of biofuels up to at least 10% of total fuel use in transportation. In meeting the 20% reduction ceiling for greenhouse gas emissions the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) will play a central role as the ‘pricing engine’ for CO 2-emissions. The higher the emissions price will be, the sooner technological emission reduction options will tend to be commercially adopted. -

Paving the Way to Carbon-Neutral Transport: 10-Point Plan To

Paving the way to carbon-neutral transport 10-point plan to help implement the European Green Deal January 2020 CONTEXT The transport sector is responsible for 22.3% of total EU greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with road transport representing 21.1% of total emissions. Breaking this down further, passenger cars account for 12.8% of Europe’s emissions, vans for 2.5%, while heavy-duty trucks and buses are responsible for 5.6%. Transport is therefore a key focus and driver for climate protection measures. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) strongly believes that carbon-neutral road transport is possible by 2050. This however will represent a seismic shift, requiring a holistic approach with increasing efforts from all stakeholders. * All CO2 equivalent ** Industry = ‘Manufacturing industries and construction’ + ‘Industrial processes and product use’ Source: European Environment Agency (EEA) AUTO INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTION Investing €57.4 billion in R&D annually, the automotive sector is Europe's largest private contributor to innovation, accounting for 28% of total EU spending. Much of this investment is dedicated to clean mobility solutions. The automobile industry embraces the Paris Agreement and its goals. Manufacturers also support the climate protection initiatives of the European Commission, such as the ‘Clean Planet for All’ strategy, provided all stakeholders contribute their share and the achievements to date are taken into account. ACEA’s 10-point plan to help implement the European Green Deal – January 2020 1 ACEA members are fully committed to deliver the ambitious 025 and 030 C2 reduction targets. In order to provide legal certainty for the industry as it moves towards carbon neutrality in 050, the 2022/2023 timeline for the revies of the regulations should be adhered to (as as endorsed by the European Council in December 201). -

Energy Budget of the Biosphere and Civilization: Rethinking Environmental Security of Global Renewable and Non-Renewable Resources

ecological complexity 5 (2008) 281–288 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ecocom Viewpoint Energy budget of the biosphere and civilization: Rethinking environmental security of global renewable and non-renewable resources Anastassia M. Makarieva a,b,*, Victor G. Gorshkov a,b, Bai-Lian Li b,c a Theoretical Physics Division, Petersburg Nuclear Physics Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, 188300 Gatchina, St. Petersburg, Russia b CAU-UCR International Center for Ecology and Sustainability, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA c Ecological Complexity and Modeling Laboratory, Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521-0124, USA article info abstract Article history: How much and what kind of energy should the civilization consume, if one aims at Received 28 January 2008 preserving global stability of the environment and climate? Here we quantify and compare Received in revised form the major types of energy fluxes in the biosphere and civilization. 30 April 2008 It is shown that the environmental impact of the civilization consists, in terms of energy, Accepted 13 May 2008 of two major components: the power of direct energy consumption (around 15 Â 1012 W, Published on line 3 August 2008 mostly fossil fuel burning) and the primary productivity power of global ecosystems that are disturbed by anthropogenic activities. This second, conventionally unaccounted, power Keywords: component exceeds the first one by at least several times. Solar power It is commonly assumed that the environmental stability can be preserved if one Hydropower manages to switch to ‘‘clean’’, pollution-free energy resources, with no change in, or Wind power even increasing, the total energy consumption rate of the civilization. -

Benefits of Emissions Trading

BENEFITS OF EMISSIONS TRADING E M I S S I O N S T R A D I N G A C H I E V E S T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L O B J E C T I V E – R E D U C E D E M I S S I O N S – A T T H E L O W E S T C O S T Cap and trade is designed to deliver an environmental outcome; the cap must be met, or there are sanctions such as fines. Allowing trading within that cap is the most effective way of minimising the cost – which is good for business and good for households. Determining physical actions that companies must take, with no flexibility, is not guaranteed to achieve the necessary reductions. Nor is establishing a regulated price, since the price required to drive reductions may take policy-makers several years to determine. Cap and trade also provides a way of establishing rigour around emissions monitoring, reporting and verification – essential for any climate policy to preserve integrity. E M I S S I O N S T R A D I N G I S B E T T E R A B L E T O R E S P O N D T O E C O N O M I C F L U C T U A T I O N S T H A N O T H E R P O L I C Y T O O L S Allowing the open market to set the price of carbon translates to better flexibility and avoids price shocks or undue burdens. -

For-75: an Ecosystem Approach to Natural Resources Management

FOR-75 An Ecosystems Approach to Natural Resources Management Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist ur nation—and especially Kentucky—has an The glade cress Oabundance of renewable natural resources, including timber, wildlife, and water. These re- sources have allowed us to build a strong nation and economy, creating one of the highest stan- dards of living in the world. As our nation grew and prospered during the past 200 years, we ex- tracted those natural resources through agricul- ture, forestry, mining, urban or industrial expansion, and other developments. Ultimately, we affected the amount of wild lands that native plants and animals need for survival. In the past, natural resources agencies have ral- The glade cress grows in Jefferson and Bullitt counties lied public support for declining wildlife popula- and nowhere else in the world. tions. In the 1930s, Congress passed the Federal Aid to Wildlife Resto- Table 1. Selected Ecosystem Declines in the ration Act, also called including the bald eagle, brown pelican, peregrine United States the Pittman-Robertson falcon, and American alligator, have recovered % Decline (loss) or Act, and state wildlife from the brink of extinction. However, numerous Ecosystem or Community Degradation agencies received fund- other species and unique habitats are declining, Pacific Northwest Old Growth Forest 90 ing to restore numerous and the list of endangered and threatened organ- Northeastern Pine Barrens 48 wildlife species that isms continues to grow every year. Why are these Tall Grass Prairie 961 were in trouble, includ- additional species in trouble, while other species Palouse Prairie 98 ing white-tailed deer, are increasing their populations and ranges? Where did we go wrong? Why, almost immedi- Blackbelt Prairies 98 wild turkeys, wood ducks, elk, and prong- ately after passage of the Endangered Species Act, Midwestern Oak Savanna 981 horn antelope. -

Analytical Environmental Agency 2 21St Century Frontiers 3 22 Four 4

# Official Name of Organization Name of Organization in English 1 "Greenwomen" Analytical Environmental Agency 2 21st Century Frontiers 3 22 Four 4 350 Vermont 5 350.org 6 A Seed Japan Acao Voluntaria de Atitude dos Movimentos por Voluntary Action O Attitude of Social 7 Transparencia Social Movements for Transparency Acción para la Promoción de Ambientes Libres Promoting Action for Smokefree 8 de Tabaco Environments Ações para Preservação dos Recursos Naturais e 9 Desenvolvimento Economico Racional - APRENDER 10 ACT Alliance - Action by Churches Together 11 Action on Armed Violence Action on Disability and Development, 12 Bangladesh Actions communautaires pour le développement COMMUNITY ACTIONS FOR 13 integral INTEGRAL DEVELOPMENT 14 Actions Vitales pour le Développement durable Vital Actions for Sustainable Development Advocates coalition for Development and 15 Environment 16 Africa Youth for Peace and Development 17 African Development and Advocacy Centre African Network for Policy Research and 18 Advocacy for Sustainability 19 African Women's Alliance, Inc. Afrique Internationale pour le Developpement et 20 l'Environnement au 21è Siècle 21 Agência Brasileira de Gerenciamento Costeiro Brazilian Coastal Management Agency 22 Agrisud International 23 Ainu association of Hokkaido 24 Air Transport Action Group 25 Aldeota Global Aldeota Global - (Global "small village") 26 Aleanca Ekologjike Europiane Rinore Ecological European Youth Alliance Alianza de Mujeres Indigenas de Centroamerica y 27 Mexico 28 Alianza ONG NGO Alliance ALL INDIA HUMAN -

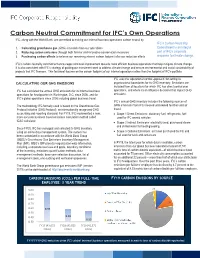

IFC Carbon Neutrality Committment Factsheet

Carbon Neutral Commitment for IFC’s Own Operations IFC, along with the World Bank, are committed to making our internal business operations carbon neutral by: IFC’s Carbon Neutrality 1. Calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from our operations Commitment is an integral 2. Reducing carbon emissions through both familiar and innovative conservation measures part of IFC's corporate 3. Purchasing carbon offsets to balance our remaining internal carbon footprint after our reduction efforts response to climate change. IFC’s carbon neutrality commitment encourages continual improvement towards more efficient business operations that help mitigate climate change. It is also consistent with IFC’s strategy of guiding our investment work to address climate change and ensure environmental and social sustainability of projects that IFC finances. This factsheet focuses on the carbon footprint of our internal operations rather than the footprint of IFC’s portfolio. IFC uses the ‘operational control approach’ for setting its CALCULATING OUR GHG EMISSIONS organizational boundaries for its GHG inventory. Emissions are included from all locations for which IFC has direct control over IFC has calculated the annual GHG emissions for its internal business operations, and where it can influence decisions that impact GHG operations for headquarters in Washington, D.C. since 2006, and for emissions. IFC’s global operations since 2008 including global business travel. IFC’s annual GHG inventory includes the following sources of The methodology IFC formally used is based on the Greenhouse Gas GHG emissions from IFC’s leased and owned facilities and air Protocol Initiative (GHG Protocol), an internationally recognized GHG travel: accounting and reporting standard. -

Trade and Environment: a Resource Book

TRADE AND ENVIRONMENT – Trade and Environment A Resource Book Trade and environment policy is increasingly intertwined and the stakes are nearly always high in both trade and environmental TRADE AND terms. These issues are often complex and discussions tend to become very specialized, challenging policy practitioners to understand and follow all the various sub-strands of trade and ENVIRONMENT environment debates. This Resource Book seeks to demystify these issues without losing the critical nuances. A RESOURCE BOOK This collaborative effort of some 61 authors from 34 countries provides relevant information as well as pertinent analysis on a broad set of trade and environment discussions while explaining, A RESOURCE BOOK as clearly as possible, what are the key issues from a trade and environment perspective; what are the most important policy debates around them; and what are the different policy positions Edited by that define these debates. Adil Najam The volume is structured and organized to be a reference document Mark Halle that is useful and easy to use. Our hope is that those actively involved in trade and environment discussions—as practitioners, Ricardo Meléndez-Ortiz as scholars and as activists—will be able to draw on the analysis Meléndez-Ortiz Najam, Mark Halle and Ricardo Adil Edited by and opinions in this book to help them advance a closer synergy between trade and environmental policy for the common goal of achieving sustainable development. T&E Resource.qx 10/17/07 4:39 PM Page i TRADE AND ENVIRONMENT A RESOURCE BOOK Edited by Adil Najam Mark Halle Ricardo Meléndez-Ortiz T&E Resource.qx 10/17/07 4:39 PM Page ii Trade and Environment: A Resource Book © 2007 International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) and the Regional and International Networking Group (The Ring). -

Biosphere Introduction the Biosphere in Education

10/5/2016 Biosphere Encyclopedia of Earth AUTHOR LOGIN EOE PAGES BROWSE THE EOE Home Article Tools: Titles (AZ) About the EoE Authors Editorial Board Biosphere Topics International Advisory Board Topic Editors FAQs Lead Author: Erle Ellis (other articles) Content Partners EoE for Educators Article Topic: Geography Content Sources Contribute to the EoE This article has been reviewed and approved by the following Topic Editor: Leszek A. eBooks Bledzki (other articles) Support the EoE Classics Last Updated: January 8, 2009 Contact the EoE Collections Find Us Here RSS Reviews Table of Contents Awards and Honors Introduction 1 Introduction The biosphere is the biological component of earth systems, which 1.1 History of the Biosphere also include the lithosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere and other Concept 2 The Biosphere in Education "spheres" (e.g. cryosphere, anthrosphere, etc.). The biosphere 3 Biosphere Research includes all living organisms on earth, together with the dead organic 4 The Future of the Biosphere matter produced by them. 5 More About the Biosphere 6 Further Reading The biosphere concept is common to many scientific disciplines including astronomy, SOLUTIONS JOURNAL geophysics, geology, hydrology, biogeography and evolution, and is a core concept in ecology, earth science and physical geography. A key component of earth systems, the biosphere interacts with and exchanges matter and energy with the other spheres, helping to drive the global biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur and other elements. From an ecological point of view, the biosphere is the "global ecosystem", comprising the totality of biodiversity on earth and performing all manner of biological functions, including photosynthesis, respiration, decomposition, nitrogen fixation and denitrification. -

Carbon Emission Reduction—Carbon Tax, Carbon Trading, and Carbon Offset

energies Editorial Carbon Emission Reduction—Carbon Tax, Carbon Trading, and Carbon Offset Wen-Hsien Tsai Department of Business Administration, National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan; [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3-426-7247 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 1. Introduction The Paris Agreement was signed by 195 nations in December 2015 to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change following the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. In Article 2 of the Paris Agreement, the increase in the global average temperature is anticipated to be held to well below 2 ◦C above pre-industrial levels, and efforts are being employed to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 ◦C. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides information on emissions of the main greenhouse gases. It shows that about 81% of the totally emitted greenhouse gases were carbon dioxide (CO2), 10% methane, and 7% nitrous oxide in 2018. Therefore, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (or carbon emissions) are the most important cause of global warming. The United Nations has made efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or mitigate their effect. In Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, three cooperative approaches that countries can take in attaining the goal of their carbon emission reduction are described, including direct bilateral cooperation, new sustainable development mechanisms, and non-market-based approaches. The World Bank stated that there are some incentives that have been created to encourage carbon emission reduction, such as the removal of fossil fuels subsidies, the introduction of carbon pricing, the increase of energy efficiency standards, and the implementation of auctions for the lowest-cost renewable energy. -

The Biosphere Reserve Program in the United States

tions recommending widespread phosphorus 15. For example, T. P. Murphy, D. R. S. Lean, visualize a laboratory bioassay experi- control as a solution to eutrophication. Almost and C. Nalewajko [Science 192, 900 (1976)] ment that could realistically represent all all of the freshwater scientists in the world were showed that Anabaena requires iron for fixation represented. of atmospheric nitrogen and that this genus of these parameters. 3. For example, see J. W. G. Lund [Nature (Lon- can suppress the growth of other species of On the basis of data from several don) 249, 797 (1974)] for a critique of phos- algae by excretion of a growth-inhibiting phorus control, including my report of the same substance. studies of the carbon, nitrogen, and year (4). 16. M. Turner and R. Flett, unpublished data. As 4. D. W. Schindler, Science 184, 897 (1974). yet no quantitative estimates of nitrogen fixation phosphorus cycle, I hypothesize that 5. P. Dillon and F. Rigler,J. Fish. Res. Board Can. for an entire season are available. G. Persson, S. schemes for controlling nitrogen input to 32, 1519 (1975); R. A. Vollenweider, Schweiz. Z. K. Holmgren, M. Jansson, A. Lundgren, and C. Hydrol. 37, 53 (1975); D. W. Schindler, Limnol. Anell [in Proceedings of the NRC-CNC lakes may actually affect water quality Oceanogr., in press. (SCOPE) Circumpolar Conference on Northern adversely by causing low N/P ratios, 6. See papers in G. E. Likens, Ed., Am. Soc. Ecology (Ottawa, 15 to 18 September 1975)] Limnol. Oceanogr. Spec. Symp. No. 1 (1972). reported similar results for a lake in Sweden that which favor the vacuolate, nitrogen-fix- 7. -

Biosphere Reserves' Management Effectiveness—A Systematic

sustainability Review Biosphere Reserves’ Management Effectiveness—A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda Ana Filipa Ferreira 1,2,* , Heike Zimmermann 3, Rui Santos 1 and Henrik von Wehrden 2 1 CENSE—Center for Environmental and Sustainability Research, NOVA College of Science and Technology, NOVA University Lisbon, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Institute of Ecology, Faculty of Sustainability and Center for Methods, Leuphana University, 21335 Lüneburg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute for Ethics and Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research, Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University, 21335 Lüneburg, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-21-294-8397 Received: 10 June 2020; Accepted: 2 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: Research about biosphere reserves’ management effectiveness can contribute to better understanding of the existing gap between the biosphere reserve concept and its implementation. However, there is a limited understanding about where and how research about biosphere reserves’ management effectiveness has been conducted, what topics are investigated, and which are the main findings. This study addresses these gaps in the field, building on a systematic literature review of scientific papers. To this end, we investigated characteristics of publications, scope, status and location of biosphere reserves, research methods and management effectiveness. The results indicate that research is conceptually and methodologically diverse, but unevenly distributed. Three groups of papers associated with different goals of biosphere reserves were identified: capacity building, biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. In general, each group is associated with different methodological approaches and different regions of the world. The results indicate the importance of scale dynamics and trade-offs between goals, which are advanced as important leverage points for the success of biosphere reserves.