US Carbon Emissions Trading Some Options That Include Downstream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for Biofuels Alongside the EU-ETS

The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS Stefan Boeters, Paul Veenendaal, Nico van Leeuwen and Hugo Rojas-Romagoza CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis Paper for presentation at the Eleventh Annual GTAP Conference ‘Future of Global Economy’, Helsinki, June 12-14, 2008 1 Table of contents Summary 3 1 The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Climate policy baseline 7 1.3 Promoting the use of biofuels 10 1.4 Increasing transport fuel excises as a policy alternative from the CO 2-emission reduction point of view 22 1.5 Conclusions 23 Appendix A: Characteristics of the WorldScan model and of the baseline scenario 25 A.1 WorldScan 25 A.2 Background scenario 27 A.3 Details of biofuel modelling 28 A.4 Sensitivity analysis with respect to land allocation 35 References 38 2 Summary The potential for biofuels alongside the EU-ETS On its March 2007 summit the European Council agreed to embark on an ambitious policy for energy and climate change that establishes several targets for the year 2020. Amongst others this policy aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20% compared to 1990 and to ensure that 20% of total energy use comes from renewable sources, partly by increasing the share of biofuels up to at least 10% of total fuel use in transportation. In meeting the 20% reduction ceiling for greenhouse gas emissions the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) will play a central role as the ‘pricing engine’ for CO 2-emissions. The higher the emissions price will be, the sooner technological emission reduction options will tend to be commercially adopted. -

NASA's Carbon Monitoring System

PAPER • OPEN ACCESS NASA’s carbon monitoring system (CMS) and arctic-boreal vulnerability experiment (ABoVE) social network and community of practice To cite this article: Molly E Brown et al 2020 Environ. Res. Lett. 15 115014 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 185.169.255.37 on 03/12/2020 at 10:13 Environ. Res. Lett. 15 (2020) 115014 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba300 Environmental Research Letters PAPER NASA’s carbon monitoring system (CMS) and arctic-boreal OPEN ACCESS vulnerability experiment (ABoVE) social network and community RECEIVED 17 April 2020 of practice REVISED 23 June 2020 Molly E Brown1,∗, Matthew W Cooper1 and Peter C Griffith2 ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION 1 6 July 2020 Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland College Park, Maryland, United States of America 2 Science Systems and Applications, Inc. and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, United States of America ∗ PUBLISHED Author to whom any correspondence should be addressed 19 November 2020 E-mail: [email protected] Original content from this work may be used Keywords: social network, carbon monitoring, Arctic environment, carbon cycle and ecosystems under the terms of the Supplementary material for this article is available online Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must Abstract maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title The NASA Carbon Monitoring System (CMS) and Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment of the work, journal citation and DOI. (ABoVE) have been planned and funded by the NASA Earth Science Division. Both programs have a focus on engaging stakeholders and developing science useful for decision making. -

Phase-Out 2020: Monitoring Europe's Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Phase-out 2020 Monitoring Europe’s fossil fuel subsidies Ipek Gençsü, Maeve McLynn, Matthias Runkel, Markus Trilling, Laurie van der Burg, Leah Worrall, Shelagh Whitley, and Florian Zerzawy September 2017 Report partners ODI is the UK’s leading independent think tank on international development and humanitarian issues. Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe is Europe’s largest coalition working on climate and energy issues. Readers are encouraged to reproduce material for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holders, ODI and Overseas Development Institute CAN Europe request due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For 203 Blackfriars Road CAN Europe online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. London SE1 8NJ Rue d’Edimbourg 26 The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not Tel +44 (0)20 7922 0300 1050 Brussels, Belgium necessarily represent the views of ODI or our partners. Fax +44 (0)20 7922 0399 Tel: +32 (0) 28944670 www.odi.org www.caneurope.org © Overseas Development Institute and CAN Europe 2017. This work is licensed [email protected] [email protected] under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Cover photo: Oil refinery in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany – Ralf Vetterle (CC0 creative commons license). 2 Report Acknowledgements The authors are grateful for support and advice on the report from: Dave Jones of Sandbag UK, Colin Roche of Friends of the Earth Europe, Andrew Scott and Sejal Patel of the Overseas Development Institute, Helena Wright of E3G, and Andrew Murphy of Transport & Environment, and Alex Doukas of Oil Change International. -

Paving the Way to Carbon-Neutral Transport: 10-Point Plan To

Paving the way to carbon-neutral transport 10-point plan to help implement the European Green Deal January 2020 CONTEXT The transport sector is responsible for 22.3% of total EU greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with road transport representing 21.1% of total emissions. Breaking this down further, passenger cars account for 12.8% of Europe’s emissions, vans for 2.5%, while heavy-duty trucks and buses are responsible for 5.6%. Transport is therefore a key focus and driver for climate protection measures. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) strongly believes that carbon-neutral road transport is possible by 2050. This however will represent a seismic shift, requiring a holistic approach with increasing efforts from all stakeholders. * All CO2 equivalent ** Industry = ‘Manufacturing industries and construction’ + ‘Industrial processes and product use’ Source: European Environment Agency (EEA) AUTO INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTION Investing €57.4 billion in R&D annually, the automotive sector is Europe's largest private contributor to innovation, accounting for 28% of total EU spending. Much of this investment is dedicated to clean mobility solutions. The automobile industry embraces the Paris Agreement and its goals. Manufacturers also support the climate protection initiatives of the European Commission, such as the ‘Clean Planet for All’ strategy, provided all stakeholders contribute their share and the achievements to date are taken into account. ACEA’s 10-point plan to help implement the European Green Deal – January 2020 1 ACEA members are fully committed to deliver the ambitious 025 and 030 C2 reduction targets. In order to provide legal certainty for the industry as it moves towards carbon neutrality in 050, the 2022/2023 timeline for the revies of the regulations should be adhered to (as as endorsed by the European Council in December 201). -

A New Era for Wind Power in the United States

Chapter 3 Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States 1 Photo from iStock 7943575 1 This page is intentionally left blank 3 Impacts of the Wind Vision Summary Chapter 3 of the Wind Vision identifies and quantifies an array of impacts associated with continued deployment of wind energy. This 3 | Summary Chapter chapter provides a detailed accounting of the methods applied and results from this work. Costs, benefits, and other impacts are assessed for a future scenario that is consistent with economic modeling outcomes detailed in Chapter 1 of the Wind Vision, as well as exist- ing industry construction and manufacturing capacity, and past research. Impacts reported here are intended to facilitate informed discus- sions of the broad-based value of wind energy as part of the nation’s electricity future. The primary tool used to evaluate impacts is the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s (NREL’s) Regional Energy Deployment System (ReEDS) model. ReEDS is a capacity expan- sion model that simulates the construction and operation of generation and transmission capacity to meet electricity demand. In addition to the ReEDS model, other methods are applied to analyze and quantify additional impacts. Modeling analysis is focused on the Wind Vision Study Scenario (referred to as the Study Scenario) and the Baseline Scenario. The Study Scenario is defined as wind penetration, as a share of annual end-use electricity demand, of 10% by 2020, 20% by 2030, and 35% by 2050. In contrast, the Baseline Scenario holds the installed capacity of wind constant at levels observed through year-end 2013. -

Estimating CO2 Emissions from Large Scale Coal-Fired Power Plants Using OCO-2 Observations and Emission Inventories

atmosphere Article Estimating CO2 Emissions from Large Scale Coal-Fired Power Plants Using OCO-2 Observations and Emission Inventories Yaqin Hu 1,2 and Yusheng Shi 1,* 1 Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101408, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-138-1042-0401 Abstract: The concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) has increased rapidly world- wide, aggravating the global greenhouse effect, and coal-fired power plants are one of the biggest contributors of greenhouse gas emissions in China. However, efficient methods that can quantify CO2 emissions from individual coal-fired power plants with high accuracy are needed. In this study, we estimated the CO2 emissions of large-scale coal-fired power plants using Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) satellite data based on remote sensing inversions and bottom-up methods. First, we mapped the distribution of coal-fired power plants, displaying the total installed capac- ity, and identified two appropriate targets, the Waigaoqiao and Qinbei power plants in Shanghai and Henan, respectively. Then, an improved Gaussian plume model method was applied for CO2 emission estimations, with input parameters including the geographic coordinates of point sources, wind vectors from the atmospheric reanalysis of the global climate, and OCO-2 observations. The application of the Gaussian model was improved by using wind data with higher temporal and spatial resolutions, employing the physically based unit conversion method, and interpolating OCO-2 observations into different resolutions. Consequently, CO2 emissions were estimated to be Citation: Hu, Y.; Shi, Y. -

Benefits of Emissions Trading

BENEFITS OF EMISSIONS TRADING E M I S S I O N S T R A D I N G A C H I E V E S T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L O B J E C T I V E – R E D U C E D E M I S S I O N S – A T T H E L O W E S T C O S T Cap and trade is designed to deliver an environmental outcome; the cap must be met, or there are sanctions such as fines. Allowing trading within that cap is the most effective way of minimising the cost – which is good for business and good for households. Determining physical actions that companies must take, with no flexibility, is not guaranteed to achieve the necessary reductions. Nor is establishing a regulated price, since the price required to drive reductions may take policy-makers several years to determine. Cap and trade also provides a way of establishing rigour around emissions monitoring, reporting and verification – essential for any climate policy to preserve integrity. E M I S S I O N S T R A D I N G I S B E T T E R A B L E T O R E S P O N D T O E C O N O M I C F L U C T U A T I O N S T H A N O T H E R P O L I C Y T O O L S Allowing the open market to set the price of carbon translates to better flexibility and avoids price shocks or undue burdens. -

Hydroelectric Power -- What Is It? It=S a Form of Energy … a Renewable Resource

INTRODUCTION Hydroelectric Power -- what is it? It=s a form of energy … a renewable resource. Hydropower provides about 96 percent of the renewable energy in the United States. Other renewable resources include geothermal, wave power, tidal power, wind power, and solar power. Hydroelectric powerplants do not use up resources to create electricity nor do they pollute the air, land, or water, as other powerplants may. Hydroelectric power has played an important part in the development of this Nation's electric power industry. Both small and large hydroelectric power developments were instrumental in the early expansion of the electric power industry. Hydroelectric power comes from flowing water … winter and spring runoff from mountain streams and clear lakes. Water, when it is falling by the force of gravity, can be used to turn turbines and generators that produce electricity. Hydroelectric power is important to our Nation. Growing populations and modern technologies require vast amounts of electricity for creating, building, and expanding. In the 1920's, hydroelectric plants supplied as much as 40 percent of the electric energy produced. Although the amount of energy produced by this means has steadily increased, the amount produced by other types of powerplants has increased at a faster rate and hydroelectric power presently supplies about 10 percent of the electrical generating capacity of the United States. Hydropower is an essential contributor in the national power grid because of its ability to respond quickly to rapidly varying loads or system disturbances, which base load plants with steam systems powered by combustion or nuclear processes cannot accommodate. Reclamation=s 58 powerplants throughout the Western United States produce an average of 42 billion kWh (kilowatt-hours) per year, enough to meet the residential needs of more than 14 million people. -

Are Biofuels an Effective and Viable Energy Strategy for Industrialized Societies? a Reasoned Overview of Potentials and Limits

Sustainability 2015, 7, 8491-8521; doi:10.3390/su7078491 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Are Biofuels an Effective and Viable Energy Strategy for Industrialized Societies? A Reasoned Overview of Potentials and Limits Tiziano Gomiero Independent Consultant and Researcher on Multi-Criteria Farming and Food System Analysis, Agro-Energies, Environmental Issues, Treviso 30121, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-32-0464-3496 Academic Editor: Andrew Kusiak Received: 7 April 2015 / Accepted: 26 June 2015 / Published: 30 June 2015 Abstract: In this paper, I analyze the constraints that limit biomass from becoming an alternative, sustainable and efficient energy source, at least in relation to the current metabolism of developed countries. In order to be termed sustainable, the use of an energy source should be technically feasible, economically affordable and environmentally and socially viable, considering society as a whole. Above all, it should meet society’s “metabolic needs,” a fundamental issue that is overlooked in the mainstream biofuels narrative. The EROI (Energy Return on Investment) of biofuels reaches a few units, while the EROI of fossil fuels is 20–30 or higher and has a power density (W/m2) thousands of times higher than the best biofuels, such as sugarcane in Brazil. When metabolic approaches are used it becomes clear that biomass cannot represent an energy carrier able to meet the metabolism of industrialized societies. For our industrial society to rely on “sustainable biofuels” for an important fraction of its energy, most of the agricultural and non-agricultural land would need to be used for crops, and at the same time a radical cut to our pattern of energy consumption would need to be implemented, whilst also achieving a significant population reduction. -

Analytical Environmental Agency 2 21St Century Frontiers 3 22 Four 4

# Official Name of Organization Name of Organization in English 1 "Greenwomen" Analytical Environmental Agency 2 21st Century Frontiers 3 22 Four 4 350 Vermont 5 350.org 6 A Seed Japan Acao Voluntaria de Atitude dos Movimentos por Voluntary Action O Attitude of Social 7 Transparencia Social Movements for Transparency Acción para la Promoción de Ambientes Libres Promoting Action for Smokefree 8 de Tabaco Environments Ações para Preservação dos Recursos Naturais e 9 Desenvolvimento Economico Racional - APRENDER 10 ACT Alliance - Action by Churches Together 11 Action on Armed Violence Action on Disability and Development, 12 Bangladesh Actions communautaires pour le développement COMMUNITY ACTIONS FOR 13 integral INTEGRAL DEVELOPMENT 14 Actions Vitales pour le Développement durable Vital Actions for Sustainable Development Advocates coalition for Development and 15 Environment 16 Africa Youth for Peace and Development 17 African Development and Advocacy Centre African Network for Policy Research and 18 Advocacy for Sustainability 19 African Women's Alliance, Inc. Afrique Internationale pour le Developpement et 20 l'Environnement au 21è Siècle 21 Agência Brasileira de Gerenciamento Costeiro Brazilian Coastal Management Agency 22 Agrisud International 23 Ainu association of Hokkaido 24 Air Transport Action Group 25 Aldeota Global Aldeota Global - (Global "small village") 26 Aleanca Ekologjike Europiane Rinore Ecological European Youth Alliance Alianza de Mujeres Indigenas de Centroamerica y 27 Mexico 28 Alianza ONG NGO Alliance ALL INDIA HUMAN -

Update on Recent Progress in Reform of Inefficient Fossil-Fuel Subsidies That Encourage Wasteful Consumption

UPDATE ON RECENT PROGRESS IN REFORM OF INEFFICIENT FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES THAT ENCOURAGE WASTEFUL CONSUMPTION Contribution by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to the G20 Energy Transitions Working Group in consultation with: International Energy Forum (IEF), Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the World Bank 2nd Energy Transitions Working Group Meeting Toyama, 18-19 April 2019 Update on Recent Progress in Reform of Inefficient Fossil-Fuel Subsidies that Encourage Wasteful Consumption This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. This update does not necessarily express the views of the G20 countries or of the IEA, IEF, OECD, OPEC and the World Bank or their member countries. The G20 countries, IEA, IEF, OECD, OPEC and the World Bank assume no liability or responsibility whatsoever for the use of data or analyses contained in this document, and nothing herein shall be construed as interpreting or modifying any legal obligations under any intergovernmental agreement, treaty, law or other text, or as expressing any legal opinion or as having probative legal value in any proceeding. Please cite this publication as: OECD/IEA (2019), "Update on recent progress in reform of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption", https://oecd.org/fossil-fuels/publication/OECD-IEA-G20-Fossil-Fuel-Subsidies-Reform-Update-2019.pdf │ 3 Summary This report discusses recent trends and developments in the reform of inefficient fossil- fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption, within the G20 and beyond. -

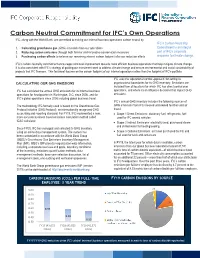

IFC Carbon Neutrality Committment Factsheet

Carbon Neutral Commitment for IFC’s Own Operations IFC, along with the World Bank, are committed to making our internal business operations carbon neutral by: IFC’s Carbon Neutrality 1. Calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from our operations Commitment is an integral 2. Reducing carbon emissions through both familiar and innovative conservation measures part of IFC's corporate 3. Purchasing carbon offsets to balance our remaining internal carbon footprint after our reduction efforts response to climate change. IFC’s carbon neutrality commitment encourages continual improvement towards more efficient business operations that help mitigate climate change. It is also consistent with IFC’s strategy of guiding our investment work to address climate change and ensure environmental and social sustainability of projects that IFC finances. This factsheet focuses on the carbon footprint of our internal operations rather than the footprint of IFC’s portfolio. IFC uses the ‘operational control approach’ for setting its CALCULATING OUR GHG EMISSIONS organizational boundaries for its GHG inventory. Emissions are included from all locations for which IFC has direct control over IFC has calculated the annual GHG emissions for its internal business operations, and where it can influence decisions that impact GHG operations for headquarters in Washington, D.C. since 2006, and for emissions. IFC’s global operations since 2008 including global business travel. IFC’s annual GHG inventory includes the following sources of The methodology IFC formally used is based on the Greenhouse Gas GHG emissions from IFC’s leased and owned facilities and air Protocol Initiative (GHG Protocol), an internationally recognized GHG travel: accounting and reporting standard.