40 Years IFSH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julia Klöckner CDU/CSU

Plenarprotokoll 15/34 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 34. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 19. März 2003 Inhalt: Änderung und Erweiterung der Tagesordnung 2701 A Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 2740 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen . 2701 D Gerhard Rübenkönig SPD . 2741 B Steffen Kampeter CDU/CSU . 2743 D Tagesordnungspunkt I: Petra Pau fraktionslos . 2746 D Zweite Beratung des von der Bundesregie- Dr. Christina Weiss, Staatsministerin BK . 2748 A rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Geset- Dr. Norbert Lammert CDU/CSU . 2749 C zes über die Feststellung des Bundeshaus- haltsplans für das Haushaltsjahr 2003 Günter Nooke CDU/CSU . 2750 A (Haushaltsgesetz 2003) Petra-Evelyne Merkel SPD . 2751 D (Drucksachen 15/150, 15/402) . 2702 B Jens Spahn CDU/CSU . 2753 D 13. Einzelplan 04 Namentliche Abstimmung . 2756 A Bundeskanzler und Bundeskanzleramt Ergebnis . 2756 A (Drucksachen 15/554, 15/572) . 2702 B Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 2702 C 19. a) Einzelplan 15 Franz Müntefering SPD . 2708 A Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale Sicherung Wolfgang Bosbach CDU/CSU . 2713 A (Drucksachen 15/563, 15/572) . 2758 B Franz Müntefering SPD . 2713 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 2714 C b) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ Otto Schily SPD . 2718 B DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Hans-Christian Ströbele BÜNDNIS 90/ wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Änderung der DIE GRÜNEN . 2719 A Vorschriften zum diagnoseorientierten Fallpauschalensystem für Kranken- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 2719 C häuser – Fallpauschalenänderungs- Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 2720 C gesetz (FPÄndG) (Drucksache 15/614) . 2758 B Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble CDU/CSU . 2724 D Dr. Michael Luther CDU/CSU . 2758 D Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . -

Appendix A—Digest of Other White House Announcements

Appendix A—Digest of Other White House Announcements The following list includes the President’s public President Vicente Fox of Mexico to discuss the schedule and other items of general interest an- situation in Argentina. nounced by the Office of the Press Secretary In the afternoon, the President traveled to and not included elsewhere in this book. Portland, OR, and later returned to the Bush Ranch in Crawford, TX. January 1 In the morning, at the Bush Ranch in January 7 Crawford, TX, the President had an intelligence In the morning, the President had an intel- briefing. ligence briefing. Later, he returned to Wash- The President issued an emergency declara- ington, DC. tion for areas struck by record and near-record The President announced the recess appoint- snowfall in New York. ment of John Magaw to be Under Secretary January 2 of Transportation for Security. In the morning, the President had an intel- The President announced his intention to ligence briefing. nominate Anthony Lowe to be Administrator of the Federal Insurance Administration at the January 3 Federal Emergency Management Agency. In the morning, the President had an intel- The President announced his intention to des- ligence briefing. ignate Under Secretary of Commerce for Inter- national Trade Grant D. Aldonas, Deputy Sec- January 4 retary of Labor Donald C. Findlay, and Under In the morning, the President had an intel- Secretary of the Treasury for International Af- ligence briefing. He then traveled to Austin, TX, and later returned to Crawford, TX. fairs John B. Taylor as members of the Board The President announced his intention to of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation. -

Sticheln Und Drohen

Deutschland Der rheinland-pfälzische Ministerpräsi- kalierenden Zwist gab es reichlich – die KOALITION dent Kurt Beck verhöhnte die Ökos gleich Russland- und China-Politik des Kanzlers, nach dem NRW-Wahldesaster als „Mops- das von Wirtschaftsminister Wolfgang Cle- Sticheln und fledermaus“-Partei, und Niedersachsens ment geschmähte Anti-Diskriminierungs- SPD-Fraktionschef Sigmar Gabriel stän- gesetz oder das aus grüner Sicht unsinnige kerte, die Grünen hätten die SPD daran Raketenabwehrsystem Meads. Drohen gehindert, Arbeitsplätze zu schaffen. „Wie haben wir über die SPD ab- Noch am späten Abend des 22. Mai be- gekotzt!“, schildert ein Teilnehmer der Das Regierungsbündnis ist schloss deren Berliner Spitze bei einer ge- wöchentlichen Gremiensitzungen den Ton heimen Zusammenkunft in der Privat- in der grünen Parteizentrale. „Jetzt ist heillos zerrüttet. Die wohnung von Fraktionschefin Katrin Scheidungskrieg.“ Grünen setzen der SPD mit Göring-Eckardt, sich nicht von den zu er- Wie weit der fortgeschritten ist, zeigt das offenen Vorwürfen zu. wartenden Beißreflexen der Sozialdemo- grüne Wahlprogramm, das der Vorstand kraten provozieren zu lassen. an diesem Montag berät. Die Sozialdemo- tto Schily ist in Eile. Seit einer Doch die verordnete Gelassenheit funk- kraten taumelten „zwischen kalter Mo- knappen halben Stunde erläutert tioniert nicht mehr. Was Schröder betreibe dernisierung und strukturkonservativer Oder Innenminister schon das neue sei „Selbstbeschädigung“, stichelt Partei- Verteidigung des Bestehenden ohne klare Informationszentrum für die WM 2006, es chef Reinhard Bütikofer. Das Urteil des Linie hin und her“, heißt es da. Ungeniert geht um Fußball und Sicherheit, darüber Bundeskanzlers – Gerhard Schröder hatte wird über die „Kohle- und Autopartei“ referiert er am liebsten. Jetzt aber drängeln schonungslos von einer Koaliton gespro- SPD hergezogen, ganz wie zuzeiten grüner seine Leute zum Aufbruch, im Bundestag chen, die quer zu den Bedürfnissen des Fundamentalkritik. -

Kleine Anfrage

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 16/3940 16. Wahlperiode 19. 12. 2006 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Undine Kurth (Quedlinburg), Katrin Göring-Eckardt, Volker Beck (Köln), Grietje Bettin, Kai Gehring, Britta Haßelmann, Priska Hinz (Herborn), Krista Sager, Renate Künast, Fritz Kuhn und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Unterstützungen für das deutsche UNESCO-Welterbe UNESCO-Welterbestätten sind ein herausragender Teil des Menschheitsge- dächtnisses. 32 deutsche Natur- und Kulturdenkmale sind auf der Welterbeliste der UNESCO verzeichnet und stehen unter deren Schutz. Die Welterbestätten bedürfen der Unterstützung für ihre Erhaltung, Erschließung und Nutzung. Auch der Bund trägt hierfür Verantwortung. Wir fragen die Bundesregierung: 1. Welche Bundesministerien und diesen nachgeordnete Bundeseinrichtungen befassen sich mit Fragen des Erhalts, der Erschließung und der Nutzung der deutschen Welterbestätten? 2. Welche Haushaltsansätze in den Einzelplänen der Bundesressorts im Bun- deshaushalt 2007 sind für die deutschen Welterbestätten relevant? 3. Welche Maßnahmen und Projekte der Bundesregierung kommen den deut- schen Welterbestätten zugute? 4. Welche finanziellen Mittel gewährten die jeweiligen Bundesministerien (gegebenenfalls einschließlich der diesen nachgeordnete Bundeseinrichtun- gen) den deutschen Welterbestätten seit 1990, und wie viel finanzielle Mit- tel flossen von Seiten des Bundes seitdem insgesamt? 5. Wie erfolgt im Bundeskanzleramt die Koordination der Aktivitäten der ver- schiedenen Bundesressorts im Bereich des deutschen Welterbes, welche personellen und finanziellen Ressourcen stehen hierfür zur Verfügung? 6. Ist der Bundesregierung bekannt, welche finanziellen Leistungen die jewei- ligen Bundesländer für ihre Welterbestätten erbringen und welche Haus- haltsansätze es hier gegebenenfalls gibt? 7. Ist der Bundesregierung bekannt, in welcher Höhe Kommunen finanzielle Leistungen für ihre Welterbestätten erbringen? 8. Wie schätzt die Bundesregierung den tatsächlichen finanziellen Bedarf der Welterbestätten in Deutschland ein? 9. -

Profile Persönlichkeiten Der Universität Hamburg Profile Persönlichkeiten Der Universität Hamburg Inhalt

FALZ FÜR EINKLAPPER U4 RÜCKENFALZ FALZ FÜR EINKLAPPER U1 4,5 mm Profile persönlichkeiten der universität hamburg Profile persönlichkeiten der universität hamburg inhalt 6 Grußwort des Präsidenten 8 Profil der Universität Portraits 10 von Beust, Ole 12 Breloer, Heinrich 14 Dahrendorf, Ralf Gustav 16 Harms, Monika 18 Henkel, Hans-Olaf 20 Klose, Hans-Ulrich 22 Lenz, Siegfried 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 Miosga, Caren 26 von Randow, Gero 28 Rühe, Volker 30 Runde, Ortwin 32 Sager, Krista 34 Schäuble, Wolfgang 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 36 Schiller, Karl 38 Schmidt, Helmut 40 Scholz, Olaf 42 Schröder, Thorsten 44 Schulz, Peter 46 Tawada, Yoko 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 48 Voscherau, Henning 50 von Weizsäcker, Carl Friedrich 52 Impressum grusswort des präsidenten Grußwort des Präsidenten der Universität Hamburg Dieses Buch ist ein Geschenk – sowohl für seine Empfänger als auch für die Universität Hamburg. Die Persönlichkeiten in diesem Buch machen sich selbst zum Geschenk, denn sie sind der Universität auf verschiedene Weise verbunden – als Absolventinnen und Absolventen, als ehemalige Rektoren, als prägende Lehrkräfte oder als Ehrendoktoren und -senatoren. Sie sind über ihre unmittelbare berufliche Umgebung hinaus bekannt, weil sie eine öffentliche Funktion wahrnehmen oder wahrgenommen haben. Die Universität Hamburg ist fern davon, sich selbst als Causa des beruflichen Erfolgs ihrer prominenten Alumni zu betrach- ten. Dennoch hat die Universität mit ihnen zu tun. Sie ist der Ort gewesen, in dem diese Frauen und Männer einen Teil ihrer Sozialisation erfahren haben. Im glücklicheren Fall war das Studium ein Teil der Grundlage ihres Erfolges, weil es Wissen, Kompetenz und Persönlichkeitsbildung ermöglichte. -

Wessen Denkmal?

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Wessen Denkmal? Zum Verhältnis von Erinnerungs- und Identitätspolitiken im Gedenken an homosexuelle NS-Opfer Verfasserin Elisa Heinrich angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 312 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Geschichte Betreuerin: A.o. Prof. Dr.in Johanna Gehmacher 2 Inhalt VORWORT ....................................................................................................................5 Zur Form geschlechtergerechter Sprache in dieser Arbeit ......................................6 1. EINFÜHRUNG ........................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Zur Physis des Denkmals / Persönliche Rezeption ....................................... 7 1.2 Ausgangspunkte und -fragen / Forschungsinteresse .................................... 14 1.3 Fragestellungen / Struktur der Arbeit .......................................................... 16 1.4 Methodische Überlegungen ...................................................................... 18 1.4.1 Grundlegendes zum Diskursbegriff ....................................................... 20 1.4.2 Material ................................................................................................ 22 1.4.3 Begrenzung und Zugangsweise ............................................................. 26 2. CHRONOLOGIE DES BERLINER ‹MAHNMALSTREITS›: Akteur_innen und Argumente ............................................................................................................ -

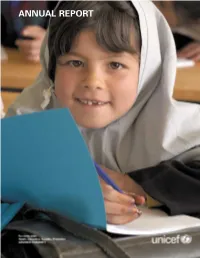

Annual Report 2002

ANNUAL REPORT KHUSHBOO GOES TO SCHOOL Khushboo, 7, whose name means ‘having a sweet scent’, is in second grade at the Ghulam Haider School in Kabul, Afghanistan. She likes being in school, and despite complaining “My teachers give me lots of homework to do…!” she says she wants to be a teacher some day. Khushboo lives in a poor neighbourhood with her family: her father, who is a messenger, her mother, a younger brother, and a 10-year-old sister who also goes to this school. UNICEF provided Khushboo’s school with learning materials and paid for teacher training. The school was one of thousands that benefited from UNICEF assistance after years of conflict and extreme poverty had nearly destroyed the country’s educa- tion system. The previous regime had banned all girls, including Khushboo’s sister, from attending school. From 2001 to 2002, UNICEF led efforts to support the Interim Administration’s ‘Back to School’ campaign. By the end of 2002, 3 million Afghan children – including 1 million girls – were back in the classroom. More children are on their way. UNICEF ANNUAL REPORT Covering 1 January to 31 December 2002 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY UNITED NATIONS SECRETARY-GENERAL KOFI A. ANNAN . 2 FOREWORD BY UNICEF EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CAROL BELLAMY . 3 OUR PRIORITIES . 5 THE EARLY YEARS . 7 IMMUNIZATION ‘PLUS’ . 10 EDUCATING GIRLS . 15 FIGHTING HIV/AIDS . 18 PROTECTING CHILDREN . 23 CHILDREN LEAD . 27 NATIONAL COMMITTEES . 28 CORPORATE ALLIANCES . 30 RESOURCES AND MANAGEMENT . 32 ACHIEVING ORGANIZATIONAL EXCELLENCE . 42 GLOBAL PARTNERSHIPS . 52 UNICEF AT WORK (list of countries) . 54 GOODWILL AMBASSADORS . 56 OUR COMMITMENTS . -

Deutscher Bundestag

Plenarprotokoll 15/34 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 34. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 19. März 2003 Inhalt: Änderung und Erweiterung der Tagesordnung 2701 A Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 2740 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen . 2701 D Gerhard Rübenkönig SPD . 2741 B Steffen Kampeter CDU/CSU . 2743 D Tagesordnungspunkt I: Petra Pau fraktionslos . 2746 D Zweite Beratung des von der Bundesregie- Dr. Christina Weiss, Staatsministerin BK . 2748 A rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Geset- Dr. Norbert Lammert CDU/CSU . 2749 C zes über die Feststellung des Bundeshaus- haltsplans für das Haushaltsjahr 2003 Günter Nooke CDU/CSU . 2750 A (Haushaltsgesetz 2003) Petra-Evelyne Merkel SPD . 2751 D (Drucksachen 15/150, 15/402) . 2702 B Jens Spahn CDU/CSU . 2753 D 13. Einzelplan 04 Namentliche Abstimmung . 2756 A Bundeskanzler und Bundeskanzleramt Ergebnis . 2756 A (Drucksachen 15/554, 15/572) . 2702 B Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 2702 C 19. a) Einzelplan 15 Franz Müntefering SPD . 2708 A Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Soziale Sicherung Wolfgang Bosbach CDU/CSU . 2713 A (Drucksachen 15/563, 15/572) . 2758 B Franz Müntefering SPD . 2713 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 2714 C b) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ Otto Schily SPD . 2718 B DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Hans-Christian Ströbele BÜNDNIS 90/ wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Änderung der DIE GRÜNEN . 2719 A Vorschriften zum diagnoseorientierten Fallpauschalensystem für Kranken- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 2719 C häuser – Fallpauschalenänderungs- Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 2720 C gesetz (FPÄndG) (Drucksache 15/614) . 2758 B Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble CDU/CSU . 2724 D Dr. Michael Luther CDU/CSU . 2758 D Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . -

Luuk Molthof Phd Thesis

Understanding the Role of Ideas in Policy- Making: The Case of Germany’s Domestic Policy Formation on European Monetary Affairs Lukas Hermanus Molthof Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of Politics and International Relations Royal Holloway, University of London September 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Lukas Hermanus Molthof, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This research aims to provide a better understanding of the role of ideas in the policy process by not only examining whether, how, and to what extent ideas inform policy outcomes but also by examining how ideas might simultaneously be used by political actors as strategic discursive resources. Traditionally, the literature has treated ideas – be it implicitly or explicitly – either as beliefs, internal to the individual and therefore without instrumental value, or as rhetorical weapons, with little independent causal influence on the policy process. In this research it is suggested that ideas exist as both cognitive and discursive constructs and that ideas simultaneously play a causal and instrumental role. Through a process tracing analysis of Germany’s policy on European monetary affairs in the period between 1988 and 2015, the research investigates how policymakers are influenced by and make use of ideas. Using five longitudinal sub-case studies, the research demonstrates how ordoliberal, (new- )Keynesian, and pro-integrationist ideas have importantly shaped the trajectory of Germany’s policy on European monetary affairs and have simultaneously been used by policymakers to advance strategic interests. -

Erhobenen Hauptes

Deutschland Es ist das alte Dilemma einer politischen Truppe, die sich als „Programmpartei“ und PARTEIEN nicht als „Funktionspartei“ verstehe, wie ein Redner betont. Ist es Verrat an grünen Erhobenen Hauptes Idealen, wenn man die Kompromisslinie eines Koalitionsvertrags auslotet? Unter Hamburgs Grünen wird – spätes- Vor den Gesprächen mit der Hamburger CDU zeigt sich tens ab Mittwoch nach den Sondierungs- gesprächen mit Ole von Beust – diese Fra- die Zerrissenheit der Grünen: Selbst die künftige Doppelspitze ge zu heftigen Debatten führen. Auf Bun- Künast/Trittin ist über das Projekt Schwarz-Grün uneins. desebene glaubt die Partei das Problem mit einem personellen Kniff lösen zu kön- s war ein Abend des gepflegten Dis- Chance, in Hamburg so etwas wie ein Mo- nen. Sie will die unterschiedlichen Lager kurses, bei Bionade und Beck’s Gold, dellprojekt für eine neue Farbenlehre in mit einer Doppelspitze einfangen. Voraus- Ein der Aula der Max-Brauer-Schule Deutschland zu schaffen – ganz ähnlich gesetzt, der Parteitag im November stimmt in Hamburg-Altona. Vielleicht lag es an wie 1985, als das erste rot-grüne Bündnis in zu, werden die Grünen mit einem Duo in der Anwesenheit von Reinhard Bütikofer, Hessen geschmiedet wurde. Doch genauso den Bundestagswahlkampf 2009 ziehen: dem Bundesvorsitzenden der Grünen, viel- deutlich zeigte sich vorige Woche die in- Renate Künast und Jürgen Trittin. leicht an den routiniert emphatischen Vor- nere Zerrissenheit der Partei. Aus praktischer Sicht hat die Zweier- trägen der Hamburger Bundestagsabge- In der norddeutschen Millionenstadt ist variante ihren Reiz: Trittin ist ein Linker, ordneten Krista Sager und Anja Hajduk: das besonders eindringlich zu besichtigen. der durch die ehemaligen Grünen-Hoch- Die gefürchtete linke Basis der Grünen Denn einerseits paktieren die Grünen be- burgen touren soll, wo die Partei zuletzt hielt sich erstaunlich zurück am vergan- reits auf lokaler Ebene mit der Union. -

Islamophobia, Xenophobia and the Climate of Hate

ISSN 1463 9696 Autumn 2006 • Bulletin No 57 EUROPEAN RACE BULLETIN Islamophobia, xenophobia and the climate of hate “It is not immigration that threatens our culture now, but nascent fascism and neo-Nazism, with the violence and intimidation that are associated with those political creeds.” Daphne Caruana Galizia, Maltese journalist Contents Preface 2 Racial violence 3 Islamophobia and xenophobia 16 National security, anti-terrorist measures and civil rights 26 The IRR is carrying out a European Race Audit supported by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Specific research projects focus on the impact of national security laws and the war against terrorism on race relations and the impact of the EU’s new policy of ‘managed migration’ on refugee protection. The Institute of Race Relations is precluded from expressing a corporate view: any opinions expressed here are therefore those of the contributors. Please acknowledge IRR’s European Race Audit Project in any use of this work. For further information contact Liz Fekete at the Institute of Race Relations, 2-6 Leeke Street, London WC1X 9HS. Email: [email protected] © Institute of Race Relations 2006 Preface In this issue of the Bulletin, we document around eighty of the most serious incidents of racial violence that have taken place across Europe over the last eleven months. These attacks occurred as the war on terror heightened prejudices against Muslims and foreigners. As Islam has been essentialised (by commentators, politicians and the media) as inherently violent and migration has been depicted as a threat to national security, 'Muslim' has become synonymous with ‘terrorist’, and migrant and foreigner with ‘crime’. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Plenarprotokoll 17/41 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 41. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 7. Mai 2010 I n h a l t : Gedenkworte zum 8. Mai 1945 ..................... Joachim Poß (SPD) ...................................... 3989 A 3991 D Otto Fricke (FDP) ........................................ Tagesordnungspunkt 23: 3993 B Zweite und dritte Beratung des von den Frak- Carsten Schneider (Erfurt) (SPD) ................. tionen der CDU/CSU und der FDP einge- 3995 A brachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Über- nahme von Gewährleistungen zum Erhalt Otto Fricke (FDP) ........................................ 3995 C der für die Finanzstabilität in der Wäh- Dr. Gesine Lötzsch (DIE LINKE) ................. 3995 D rungsunion erforderlichen Zahlungsfähig- Renate Künast (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) ....................................... 3998 B keit der Hellenischen Republik (Wäh- Dr. Gesine Lötzsch (DIE LINKE) ................. 4000 B rungsunion-Finanzstabilitätsgesetz – Renate Künast (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) ....................................... WFStG) 4000 C Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister (Drucksachen 17/1544, 17/1561, 17/1562) .... BMF ........................................................ 3989 D 4001 A Sigmar Gabriel (SPD) .................................. Norbert Barthle (CDU/CSU) ........................ 4003 B 3990 B II Deutscher Bundestag – 17. Wahlperiode – 41. Sitzung, Berlin, Freitag, den 7. Mai 2010 Otto Fricke (FDP) .................................... rung 4005 A (Drucksache 17/865) ............................... 4031