Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German Porcelain Figural Group

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German porcelain figural group, depicting a pianist and dancers, each dressed in classical $ 500 $ 700 attire with crinoline accents, marked with underglaze blue mark, 11.5"h x 16"w x 9"d 7001 Framed group of 32 Wedgwood jasperware medallions, each depicting British royalty, $ 300 $ 500 overall 17.5"h x 33"w 7002 (lot of 2) Continental polychrome decorated pill boxes, including a Meissen example, $ 300 $ 500 largest 1"h x 2.5"w 7003 (lot of 2) Meissen figural candlestick group 19th century, each depicted holding a child, one $ 1,200 $ 1,500 figure in the Bacchanalian taste, having a grape cluster wreath, each depicted in Classical attire, and rising on a Rococco style base with bird form reserves, underside with underglaze blue cross sword mark, 13,5"h 7004 Continental style gilt bronze footed compote, having a garland swag decorated frieze $ 600 $ 900 flanking the ebonized bowl, above the fish form gilt bronze standard, and rising on a circular marble base, 8.5"h x 8"w 7005 (lot of 8) French hand painted porcelain miniature portraits; each depicting French royalty $ 800 $ 1,200 including Napoleon, and numerous ladies, largest 4"h x 3"w Provenance: from the Holman Estate in Pacific Grove. The Holman family were early residents of the Monterey Peninsula and established Holman's Department Store in the center of Pacific Grove, thence by family descent 7006 French Grand Tour style silver gilt mythological figure, depicting Bacchus or Dionysus, $ 1,500 $ 2,000 modeled as standing on a mound of grapes and leaves holding -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

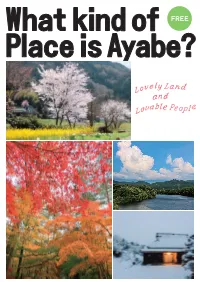

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

A Garden in Uji Embodying the Yearning for the Paradise in The

II SUGIMOTO Hiroshi A Garden in Uji Embodying the Yearning for the Paradise in the West – Byôdô-in Garden – SUGIMOTO Hiroshi Sub-Manager, Historic City Planning Promotion Section, Uji City, JAPAN 1. Creation of Byôdô-in (south-facing temple building) and a pond are located on In the Heian period (794 to 1185), Uji was developed the south-north axis extending from the Nan-mon (south in the southern Heian-kyô (present-day Kyôto) as a gate), and the pond is surrounded by the U shaped temple. residential suburb. The preceding building of Byôdô-in was Byôdô-in is significantly different in these features from the originally built in the early Heian period as a private villa for other two temples. The building style of the Phoenix Hall Minamoto no Tôru, which was later purchased by Fujiwara was taken over by Shôkômyô-in in Toba and Muryôkô-in in no Michinaga. After being bequeathed to his son Fujiwara Hiraizumi, exerting a significant impact on the development no Yorimichi, the villa was converted into a temple in 1052, of Jôdo temples in later years. which coincided with the beginning of the mappô, the age of the degeneration of the Buddha’s law. The main hall of the 2. Byôdô-in Garden villa was then renovated into a Buddhist sanctum and the It is obvious, both from records and the layout, that the Phoenix Hall (Hô-oh-dô) was added in the following year. Phoenix Hall is the main building of the Byôdô-in temple The Fujiwara clan continued expanding the building and, by complex. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

Japanese Garden

満開 IN BLOOM A PUBLICATION FROM WATERFRONT BOTANICAL GARDENS SPRING 2021 A LETTER FROM OUR 理事長からの PRESIDENT メッセージ An opportunity was afforded to WBG and this region Japanese Gardens were often built with tall walls or when the stars aligned exactly two years ago! We found hedges so that when you entered the garden you were out we were receiving a donation of 24 bonsai trees, the whisked away into a place of peace and tranquility, away Graeser family stepped up with a $500,000 match grant from the worries of the world. A peaceful, meditative to get the Japanese Garden going, and internationally garden space can teach us much about ourselves and renowned traditional Japanese landscape designer, our world. Shiro Nakane, visited Louisville and agreed to design a two-acre, authentic Japanese Garden for us. With the building of this authentic Japanese Garden we will learn many 花鳥風月 From the beginning, this project has been about people, new things, both during the process “Kachou Fuugetsu” serendipity, our community, and unexpected alignments. and after it is completed. We will –Japanese Proverb Mr. Nakane first visited in September 2019, three weeks enjoy peaceful, quiet times in the before the opening of the Waterfront Botanical Gardens. garden, social times, moments of Literally translates to Flower, Bird, Wind, Moon. He could sense the excitement for what was happening learning and inspiration, and moments Meaning experience on this 23-acre site in Louisville, KY. He made his of deep emotion as we witness the the beauties of nature, commitment on the spot. impact of this beautiful place on our and in doing so, learn children and grandchildren who visit about yourself. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

Newsletter 13 (June 2014)

June 2014 - Volume 6 - Issue 2 June 2014 - Volume 6 - Issue 2 国際基督教大学ロータリー平和センター ニューズレター ICU Rotary Peace Center Newsletter Rotary Peace Center Staff Director: Masaki Ina Associate Director: Giorgio Shani G.S. Office Manager: Masako Mitsunaga Coordinator: Satoko Ohno Contact Information: Rotary Peace Center International Christian University 3-10-2 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8585 Tel: +81 422 33 3681 Fax: +81 422 33 3688 [email protected] http://subsite.icu.ac.jp/rotary/ Index In this issue: 2 - Trailblazing Events 4 - Preparing For Peace 5 - Experiential Learning Reflections 7 - Meet The Families of Class XII Fellows 10 - Class XI Thesis Summaries 15 - Class XII AFE Placements 16 - Gratitude and Appreciation from Class XII 1 Trailblazing Events ICU Celebrates First Ever Black History Month by Nixon Nembaware Being an International University, ICU brings together students and Faculty members of various backgrounds and races. It is thus a suitable place to cultivate understanding of different cultures and heritages. This was the thinking that Rotary Peace Fellow Class XII had in mind when they partnered with the Social Science Research Institute to celebrate the first ever Black History Month commemoration at ICU. Two main events were lined up, first was a dialogue with Dr. Mohau Pheko, Ambassador of the Republic of South Africa to Japan who visited our campus to give an open lecture on the legacy of ‘Nelson Mandela’ and the history of black people in South Africa. Second was a dialogue with Ms. Judith Exavier, Ambassador of the Republic of Haiti to Japan. She talked of the history of the black people in the Caribbean Island and linked the history of slavery to what prospects lie ahead for black people the world over. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN Arrive Yokohama: 0800 Sunday, January 27 Onboard Yokohama: 2100 Monday, January 28 Arrive Kobe: 0800 Wednesday, January 30 Onboard Kobe: 1800 Thursday, January 31 Brief Overview: The "Land of the Rising Sun" is a country where the past meets the future. Japanese culture stretches back millennia, yet has created some of the latest modern technology and trends. Japan is a study in contrasts and contradictions; in the middle of a modern skyscraper you might discover a sliding wooden door which leads to a traditional chamber with tatami mats, calligraphy, and tea ceremony. These juxtapositions mean you may often be surprised and rarely bored by your travels in Japan. Voyagers will have the opportunity to experience Japanese hospitality first-hand by participating in a formal tea ceremony, visiting with a family in their home in Yokohama or staying overnight at a traditional ryokan. Japan has one of the world's best transport systems, which makes getting around convenient, especially by train. It should be noted, however, that travel in Japan is much more expensive when compared to other Asian countries. Japan is famous for its gardens, known for its unique aesthetics both in landscape gardens and Zen rock/sand gardens. Rock and sand gardens can typically be found in temples, specifically those of Zen Buddhism. Buddhist and Shinto sites are among the most common religious sites, sure to leave one in awe. From Yokohama: Nature lovers will bask in the splendor of Japan’s iconic Mount Fuji and the Silver Frost Festival. Kamakura and Tokyo are also nearby and offer opportunities to explore Zen temples and be led in meditation by Zen monks. -

The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical

The University of Iceland School of Humanities Japanese Language and Culture The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical How Shinto, Daoism, Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism Interplay in the Ritual Space of Japanese Tea Ceremony BA Essay in Japanese Language and Culture Francesca Di Berardino Id no.: 220584-3059 Supervisor: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2018 Abstract Japanese tea ceremony extends beyond the mere act of tea drinking: it is also known as chadō, or “the Way of Tea”, as it is one of the artistic disciplines conceived as paths of religious awakening through lifelong effort. One of the elements that shaped its multifaceted identity through history is the evolution of the physical space where the ritual takes place. This essay approaches Japanese tea ceremony from a point of view that is architectural and anthropological rather than merely aesthetic, in order to trace the influence of Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism on both the architectural elements of the tea room and the different aspects of the ritual. The structure of the essay follows the structure of the space where the ritual itself is performed: the first chapter describes the tea garden where guests stop before entering the ritual space of the tea room; it also provides an overview of the history of tea in Japan. The second chapter figuratively enters the ritual space of the tea room, discussing how Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism merged into the architecture of the ritual space. Finally, the third chapter looks at the preparation room, presenting the interplay of the four cognitive systems within the ritual of making and serving tea. -

K Kan Nsai I in Th He a Asia Paci Ific

ISBN 978-4-87769-650-4 APIR Published by Asia Pacific Institute of Research Kansai Kansai Kansai iin the Asia Pacific in in Kansai Toward a New Growth Paradigm the the AsiaAsia Pacific 財団法人 Pacific 関西社会経済研究所 as a Regional Hub Kyushu Shinkansen Tokyo Skytree Photo provided by West Japan Railway Co., Ltd. Photo provided by Panasonic Corporation Supported by Tokyo-Hotaru (東京ホタル®) Executive Committee Shooting Date: May 6th, 2012 Asia Pacific Institute of RResearch, Osaka 財団法人 Asia Pacific Institute of Research 関西社会経済研究所 Knowledge Capital Tower C, The Grand Front Osaka, 3-1 Ofuka-chou, Kitaku, Osaka 530-0011 Japan Tel:81-(0)6-6485-7690 Email:[email protected] URL:http://www.apir.or.jp Photo on the cover: Kansai International Airport Photo provided by New Kansai International Airport Co., Ltd. K Kaannssaaii iinn tthhee AAssiiaa PPaacciiffiicc Toward a New Growth Paradigm Asia Pacific Institute of Research, Osaka ISBN 978-4-87769-650-4 Kansai in the Asia Pacific Toward a New Growth Paradigm Copyright ⓒ 2013 by Asia Pacific Institute of Research All rights reserved. Published by Asia Pacific Institute of Research, March 2013. The regional division in this book is as follows unless otherwise noted. Kansai: prefectures of Fukui, Shiga, Kyoto, Osaka, Hyogo, Nara, Wakayama Kanto: prefectures of Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, Saitama, Chiba, Kanagawa, Yamanashi and Tokyo Metropolis Chubu: prefectures of Nagano, Gifu, Shizuoka, Aichi, Mie Japan: all prefectures including Kansai, Kanto and Chubu The abstract maps used herein are for illustration purpose only. They are not taken from official sources and do not necessarily represent territorial claims and boundaries.