The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German Porcelain Figural Group

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German porcelain figural group, depicting a pianist and dancers, each dressed in classical $ 500 $ 700 attire with crinoline accents, marked with underglaze blue mark, 11.5"h x 16"w x 9"d 7001 Framed group of 32 Wedgwood jasperware medallions, each depicting British royalty, $ 300 $ 500 overall 17.5"h x 33"w 7002 (lot of 2) Continental polychrome decorated pill boxes, including a Meissen example, $ 300 $ 500 largest 1"h x 2.5"w 7003 (lot of 2) Meissen figural candlestick group 19th century, each depicted holding a child, one $ 1,200 $ 1,500 figure in the Bacchanalian taste, having a grape cluster wreath, each depicted in Classical attire, and rising on a Rococco style base with bird form reserves, underside with underglaze blue cross sword mark, 13,5"h 7004 Continental style gilt bronze footed compote, having a garland swag decorated frieze $ 600 $ 900 flanking the ebonized bowl, above the fish form gilt bronze standard, and rising on a circular marble base, 8.5"h x 8"w 7005 (lot of 8) French hand painted porcelain miniature portraits; each depicting French royalty $ 800 $ 1,200 including Napoleon, and numerous ladies, largest 4"h x 3"w Provenance: from the Holman Estate in Pacific Grove. The Holman family were early residents of the Monterey Peninsula and established Holman's Department Store in the center of Pacific Grove, thence by family descent 7006 French Grand Tour style silver gilt mythological figure, depicting Bacchus or Dionysus, $ 1,500 $ 2,000 modeled as standing on a mound of grapes and leaves holding -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Look Through the Heart Teahouse”

ShinKanAn Teahouse – The “Look Through the Heart Teahouse” 1. Introduction: History and Name • Our Teahouse in unique on the Central Coast. It is a traditional structure, using mostly Japanese joinery instead of nails, traditional tatami mats and hand-made paper sliding doors. Additionally, it is perhaps the only traditional Japanese Teahouse between the Greater Los Angeles area and the San Francisco peninsula, and the only one in California using California natives in an intentional Japanese style. • It was originally built in Kyoto during the postwar period: a wooden plaque on the wall near the entry doors commemorates the architect and the date: 1949. The Teahouse was a gift from the President of the Nippon Oil Company to a local resident, Mr. H. Royce Greatwood, as an expression of appreciation for his assistance after the war. It was shipped in wooden boxes, each piece numbered, and reassembled in Mr. Greatwood’s Hope Ranch lemon orchard in the early 1950’s. This teahouse is evidence of the tremendous efforts that were made to renew the ties of friendship between former wartime adversaries. • The rich cultural tradition of Cha-do, The Way of Tea, graces this teahouse. In 2000, it was given the name ShinKanAn , meaning “Look Through the Heart” by the 15th Grandmaster of the Urasenke Tea school, an unusual event. • The name was generously given in honor of Heartie Anne Look, a teacher of flower arrangement and Japanese culture for many years in the Santa Barbara community. This teahouse is being used and maintained in a manner authentic to the tradition of Cha-do. -

Based on the Most Classic Cocktails, but with an Asian Twist, These Cocktails Have Been Created by Roji for Anyone Who Follows the Path of Roji

Based on the most classic cocktails, but with an Asian twist, these cocktails have been created by Roji for anyone who follows the path of Roji. Please feel free to order your favorite classic cocktail even if it is not mentioned on this menu. The Nomu 13 Ketel One Vodka, Cointreau, Yuzu, Litchi, Bitters, Egg White Sweet with a Japanese twist Walking To Paradise 14 Johnnie Walker Black Label, Raspberry Liqueur, Lime, Butterscotch, Egg white Keep Walking... Budo 13 Hendrick’s Gin, Cointreau,Grapes, Cucumber, Elderfower, Lime Perfect Start Of Your Wonderful Evening Rojitini 14 Mount Gay Eclipse Rum, Elderfower, Lime Sweet & Classy Mao 15 Mount Gay Eclipse Rum, Zacapa 23 Rum, Lime, Liquor 43, Almond Syrup, Bitters Tiki Style Man with the Red Face 14 Strawberry and basil infused Don Julio Bianco, dry vermouth, lime Spicy challenge My Medicine Penicillin 16 Monkey Shoulder Whiskey, Laphroaig 10, Ginger syrup, Honey syrup, lime Smokey, Spicy A Bitter Berry 14 Tanqueray N°Ten, Campari, Homemade Strawberry Shiso shrub Twist on a Negroni After Dinner Cocktails Smokey ‘Cohiba’ Crusta 15 Zacapa 23, Maraschino liquor, Cherry Brandy, Lime, Smoke It’s Allowed To Smoke Inside... Gentlemen’s Agreement Club 29 Johnnie Walker Blue Label, Px Sherry, Poire Williams Eau de Vie, Bitters The Perfect After Dinner at The Fire Place Lost in Translation 14 Bulleit Rye Whiskey, Fernet Branca, Sugar, Bitters Champagne Cocktails Bellefeur Champagne 14 Roji Champagne, Elderfower ‘Belfeur’ The New Bellini Champagne Russian S. Punch 15 Belvedere Vodka, Raspberry Liqueur, Crème de Cassis Topped With Our Own Roji Champagne... Roji’s Mocktails Bangkok Non-Stop 7 Blue Eyes Tea, Litchi Syrup, Ginger Syrup, Yuzu Juice and Coke. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods: vast majority, who were based in urban centers, could ill afford to be indifferent to money and the Diaries of the Toyama Family commerce. Largely divorced from the land and of Hachinohe incumbent upon the lord for their livelihood, usually disbursed in the form of stipends, samu- © Constantine N. Vaporis, University of rai were, willy-nilly, drawn into the commercial Maryland, Baltimore County economy. While the playful (gesaku) literature of the late Tokugawa period tended to portray them as unrefined “country samurai” (inaka samurai, Introduction i.e. samurai from the provincial castle towns) a Samurai are often depicted in popular repre- reading of personal diaries kept by samurai re- sentations as indifferent to—if not disdainful veals that, far from exhibiting a lack of concern of—monetary affairs, leading a life devoted to for monetary affairs, they were keenly price con- the study of the twin ways of scholastic, meaning scious, having no real alternative but to learn the largely Confucian, learning and martial arts. Fu- art of thrift. This was true of Edo-based samurai kuzawa Yukichi, reminiscing about his younger as well, despite the fact that unlike their cohorts days, would have us believe that they “were in the domain they were largely spared the ashamed of being seen handling money.” He forced paybacks, infamously dubbed “loans to maintained that “it was customary for samurai to the lord” (onkariage), that most domain govern- wrap their faces with hand-towels and go out ments resorted to by the beginning of the eight- after dark whenever they had an errand to do” in eenth century.3 order to avoid being seen engaging in commerce. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

The Lesson of the Japanese House

Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XV 275 LEARNING FROM THE PAST: THE LESSON OF THE JAPANESE HOUSE EMILIA GARDA, MARIKA MANGOSIO & LUIGI PASTORE Politecnico di Torino, Italy ABSTRACT Thanks to the great spiritual value linked to it, the Japanese house is one of the oldest and most fascinating architectural constructs of the eastern world. The religion and the environment of this region have had a central role in the evolution of the domestic spaces and in the choice of materials used. The eastern architects have kept some canons of construction that modern designers still use. These models have been source of inspiration of the greatest minds of the architectural landscape of the 20th century. The following analysis tries to understand how such cultural bases have defined construction choices, carefully describing all the spaces that characterize the domestic environment. The Japanese culture concerning daily life at home is very different from ours in the west; there is a different collocation of the spiritual value assigned to some rooms in the hierarchy of project prioritization: within the eastern mindset one should guarantee the harmony of spaces that are able to satisfy the spiritual needs of everyone that lives in that house. The Japanese house is a new world: every space is evolving thanks to its versatility. Lights and shadows coexist as they mingle with nature, another factor in understanding the ideology of Japanese architects. In the following research, besides a detailed description of the central elements, incorporates where necessary a comparison with the western world of thought. All the influences will be analysed, with a particular view to the architectural features that have influenced the Modern Movement. -

Delft University of Technology Tatami

Delft University of Technology Tatami Hein, Carola Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Published in Kyoto Design Lab. Citation (APA) Hein, C. (2016). Tatami. In A. C. de Ridder (Ed.), Kyoto Design Lab.: The tangible and the intangible of the Machiya House (pp. 9-12). Delft University of Technology. Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. TATAMI Inside the Shōkin-tei, located in the garden of the Katsura Imperial Villa. A joint of three tatami. Tatami Carola Hein Use of the tatami mat reportedly goes back to the 8th century (the Nara period in Japan) when single mats began to be used as beds, or brought out for a high-ranking person to sit on. Over centuries it became a platform that has hosted all facets of life for generations of Japanese. From palaces to houses, from temples to spaces for martial art, the tatami has served as support element for life. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

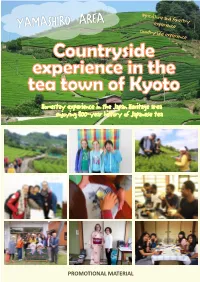

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

The Superlative Artistry of Japan

The Superlative Artistry of Japan gikou_fix.indd 1 2018/02/28 21:41 Foreword The Japan Foundation is a specialized public agency, which was established in 1972 with the goal of promoting international understanding through cultural exchange. The foundation organizes a variety of projects in three primary areas of activity: arts and cultural exchange, Japanese-language education abroad, and Japanese studies and intellectual exchange. In the field of visual arts, part of our arts and cultural exchange program, we strive to introduce Japanese art through reciprocal exchanges between Japan and other countries. As part of these activities, we have regularly organized traveling exhibitions, which tour the world. These events are made up of works from the foundation’s own collection and deal with a diverse range of subjects including crafts, painting, photography, architecture, and design. Some 20 exhibitions are constantly underway and are held at some 100 cities every year. On this occasion we are pleased to present “The Superlative Artistry of Japan”, a traveling exhibition that presents a cohesive collection of works and materials from various different genres that each place great emphasis on highly skilled techniques, ingenious expressions and concepts, and a high level of perfection that take viewers by surprise. Introducing elaborate Meiji era (1868 – 1912) kogei works that played a significant role in initiating the Japonism trend in 19th century Europe as a starting point, the exhibition in addition to numerous contemporary works of superlative artistry, also comprises capsule toy figures and food samples that illustrate a strong commitment to craftsmanship. Through this exhibition we intend to introduce the outstanding techniques of each work as well as the worlds of expression that even serve to surpass such skill and finesse, in hopes that viewers will be able to appreciate this specific part of Japan’s creative culture that honors craftsmanship and has constantly shown a thorough sense of meticulousness and devotion towards production processes.