Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

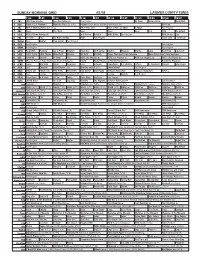

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Univerzita Karlova V Praze Filozofická Fakulta

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav Dálného východu Bakalářská práce Kateřina Danišová Vztah umění a vytváření japonské národní identity v moderním období The Relation of Art and Japanese National Identity in the Modern Era Praha, 2011 vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Labus, Ph.D. Poděkování Tímto bych chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Davidu Labusovi, Ph.D., za vedení práce, užitečné rady a připomínky. Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, že jsem řádně citovala všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze dne 9.7.2011 podpis Anotace Bakalářská práce se zaměřuje na představení nových západních uměleckých technik, které se v Japonsku rozšířily během období Meidži, dále na způsob jejich interakce s tradičními žánry a formami. Soustřeďuje se na role jedinců, zejména Ernesta Fenollosy a Okakury Tenšina, spolků a institucí při vytváření vědomí národní identity a také na roli, kterou kultura zastala ve vznikající moderní ideologii. Annotation This bachelor dissertation concentrates on the introduction of the new artistic techniques, which spread out in Japan during the Meiji period, and on their interaction with the traditional genres and forms. It examines the role of individuals, particularly Ernest Fenollosa and Okakura Tenshin, societies and institutions in the process of creating a national identity. It also deals with the part of the culture in the developing of a modern ideology. Klíčová slova Japonsko, japonské umění, umění v období Meidži, národní identita, interakce tradičního a moderního umění, moderní japonské umění, Okakura, Fenollosa, Conder, jóga, nihonga. Keywords Japan, japanese art, Meiji period art, national identity, traditional and modern art interaction, japanese modern art, Okakura, Fenollosa, Conder, jōga, nihonga. -

Issue Print Test | Nonsite.Org

ISSUE #13: THE LATIN AMERICAN ISSUE 13 nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2015 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren FOR AUTHORS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

2018 Issued BL 11192018 by DATE

2018 Issued Tukwila Business Licenses Sorted by Date of Application DBA Name Full Name Full Primary Address UBC # NAICS Creation NAICS Description Code Date TROYS ELECTRIC EDWARDS TROY A 2308 S L ST 602712157 238210 11/13/2018 Electrical Contractors TACOMA WA 98405 and Oth OLD MACK LLC OLD MACK LLC 2063 RYAN RD 604216260 423320 11/13/2018 Brick, Stone, and BUCKLEY WA 98321 Related Cons DRAGONS BREATH CREAMERY NITRO SNACK LLC 1027 SOUTHCENTER MALL 604290130 445299 11/9/2018 All Other Specialty Food TUKWILA WA 98188 Store NASH ELECTRIC LLC NASH ELECTRIC LLC 8316 71ST ST NE 603493097 238210 11/8/2018 Electrical Contractors MARYSVILLE WA 98270 and Oth BUDGET WIRING BUDGET WIRING 12612 23RD AVE S 601322435 238210 11/7/2018 Electrical Contractors BURIEN WA 98168 and Oth MATRIX ELECTRIC LLC MATRIX ELECTRIC LLC 15419 24TH AVE E 603032786 238210 11/7/2018 Electrical Contractors TACOMA WA 98445-4711 and Oth SOUNDBUILT HOMES LLC SOUNDBUILT HOMES LLC 12815 CANYON RD E 602883361 236115 11/7/2018 General Contractor M PUYALLUP WA 98373 1ST FIRE SOLUTIONS LLC 1ST FIRE SOLUTIONS LLC 4210 AUBURN WAY N 603380886 238220 11/6/2018 Plumbing, Heating, and 7 Air-Con AUBURN WA 98002 BJ'S CONSTRUCTION & BJ'S CONSTRUCTION & 609 26TH ST SE 601930579 236115 11/6/2018 General Contractor LANDSCAPING LANDSCAPING AUBURN WA 98002 CONSTRUCTION BROKERS INC CONSTRUCTION BROKERS INC 3500 DR GREAVES RD 604200594 236115 11/6/2018 General Contractor GRANDVIEW MO 64030 OBEC CONSULTING ENGINEERS OBEC CONSULTING ENGINEERS 4041 B ST 604305691 541330 11/6/2018 Engineering Services -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Making Icons

Making Icons Repetition and the Female Image in Japanese Cinema, 1945–1964 Jennifer Coates Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-99-9 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements viii Notes on the Romanization of Japanese Words x Introduction 1 Aff ect and the Spectator 4 From Emotion, through Aff ect, to Fantasy 12 Communal Fantasies: Making Meaning and Memory through Film 17 Women in Post-war Japan 21 Reading the Female Image: An Iconographic Approach 22 Chapter Outline 30 Chapter 1 Post-war Stars and the Japanese Studio System 33 Stars and the Studios 44 Compliance and Confl ict in the Studios: Th e Tōhō Strikes 49 Aff ect and Aspiration: Th e Star Persona of Hara Setsuko 54 Misora Hibari, Yamaguchi Yoshiko, and the ‘New Faces’ 62 Chapter 2 Th e Suff ering Mother Trope 68 Suff ering Mothers versus Modern Housewives 68 Historical Contexts: Changing Japan from the Family Level Up 70 From Victim to Victimizer: Changes in the Mother -

Watanabe, Tokyo, E

Edition Axel Menges GmbH Esslinger Straße 24 D-70736 Stuttgart-Fellbach tel. +49-711-574759 fax +49-711-574784 Hiroshi Watanabe The Architecture of Tokyo 348 pp. with 330 ill., 161,5 x 222 mm, soft-cover, English ISBN 3-930698-93-5 Euro 36.00, sfr 62.00, £ 24.00, US $ 42.00, $A 68.00 The Tokyo region is the most populous metropolitan area in the world and a place of extraordinary vitality. The political, economic and cultural centre of Japan, Tokyo also exerts an enormous inter- national influence. In fact the region has been pivotal to the nation’s affairs for centuries. Its sheer size, its concentration of resources and institutions and its long history have produced buildings of many different types from many different eras. Distributors This is the first guide to introduce in one volume the architec- ture of the Tokyo region, encompassing Tokyo proper and adja- Brockhaus Commission cent prefectures, in all its remarkable variety. The buildings are pre- Kreidlerstraße 9 sented chronologically and grouped into six periods: the medieval D-70806 Kornwestheim period (1185–1600), the Edo period (1600–1868), the Meiji period Germany (1868–1912), the Taisho and early Showa period (1912–1945), the tel. +49-7154-1327-33 postwar reconstruction period (1945–1970) and the contemporary fax +49-7154-1327-13 period (1970 until today). This comprehensive coverage permits [email protected] those interested in Japanese architecture or culture to focus on a particular era or to examine buildings within a larger temporal Buchzentrum AG framework. A concise discussion of the history of the region and Industriestraße Ost 10 the architecture of Japan develops a context within which the indi- CH-4614 Hägendorf vidual works may be viewed. -

Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages by Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University)

Vegetables and the Diet of the Edo Period, Part 2 Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages By Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University) Introduction compiled by Tomita Iyahiko and completed in 1873, describes the geography and culture of Hida During the Edo period (1603–1868), the number of province. It contains records from 415 villages in villages in Japan remained fairly constant with three Hida counties, including information on land roughly 63,200 villages in 1697 and 63,500 140 years value, number of households, population and prod- later in 1834. According to one source, the land ucts, which give us an idea of the lifestyle of these value of an average 18th and 19th century village, with villagers at the end of the Edo period. The first print- a population of around 400, was as much as 400 to ed edition of Hidago Fudoki was published in 1930 500 koku1, though the scale and character of each vil- (by Yuzankaku, Inc.), and was based primarily on the lage varied with some showing marked individuality. twenty-volume manuscript held by the National In one book, the author raised objections to the gen- Archives of Japan. This edition exhibits some minor eral belief that farmers accounted for nearly eighty discrepancies from the manuscript, but is generally percent of the Japanese population before and during identical. This article refers primarily to the printed the Edo period. Taking this into consideration, a gen- edition, with the manuscript used as supplementary eral or brief discussion of the diet in rural mountain reference.