The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duckduckgo Search Engines Android

Duckduckgo search engines android Continue 1 5.65.0 10.8MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.64.0 10.8MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.63.1 10.78MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.62.0 10.36MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.61.2 10.36MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.60.0 10.35MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.59.1 10.35MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.58.1 10.33MB DuckduckGo Privacy Browser 1 5.57.1 10.31MB DuckduckGo Privacy browser © DuckduckGo. Privacy, simplified. This article is about the search engine. For children's play, see duck, duck, goose. Internet search engine DuckDuckGoScreenshot home page DuckDuckGo on 2018Type search engine siteWeb Unavailable inMultilingualHeadquarters20 Paoli PikePaoli, Pennsylvania, USA Area servedWorldwideOwnerDuck Duck Go, Inc., createdGabriel WeinbergURLduckduckgo.comAlexa rank 158 (October 2020 update) CommercialRegregedSeptember 25, 2008; 12 years ago (2008-09-25) was an Internet search engine that emphasized the privacy of search engines and avoided the filter bubble of personalized search results. DuckDuckGo differs from other search engines by not profiling its users and showing all users the same search results for this search term. The company is based in Paoli, Pennsylvania, in Greater Philadelphia and has 111 employees since October 2020. The name of the company is a reference to the children's game duck, duck, goose. The results of the DuckDuckGo Survey are a compilation of more than 400 sources, including Yahoo! Search BOSS, Wolfram Alpha, Bing, Yandex, own web scanner (DuckDuckBot) and others. It also uses data from crowdsourcing sites, including Wikipedia, to fill in the knowledge panel boxes to the right of the results. -

BA Thesis an Overview of Stereotyped Portrayals of LGBT+ People In

BA thesis in Japanese Language and Culture An Overview of Stereotyped Portrayals of LGBT+ People in Japanese Fiction and Literature Analysis of the historical evolution and commercialization of BL and yuri genres, and social practice of its consumer culture Bára B.S. Jóhannesdóttir Supervisor Kristín Ingvarsdóttir May 2021 FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt Mál og Menning An Overview of Stereotyped Portrayals of LGBT+ People in Japanese Fiction and Literature Analysis of the historical evolution and commercialization of BL and yuri genres, and social practice of its consumer culture Ritgerð til BA-prófs 10 ECTS Bára B.S. Jóhannesdóttir Kt.: 210496-2039 Leiðbeinandi: Kristín Ingvarsdóttir Maí 2021 1 Abstract This essay will explore the history of the portrayal of LGBT+ people in Japanese fiction, starting from The Tale of Genji, a novel from the early 11th century that is widely considered to be the first classic in history, and to the proper establishment of what is known as the BL (boys’ love) and yuri genres. BL, as the name suggests, is a genre that features the relationship between two male characters, usually in a romantic and/or sexual nature, while yuri is between two female characters. There will be a short examination of LGBT+ portrayal in historical literary works and art before moving onto a more detailed recounting of modern fiction and television. Some ancient literature will be reviewed, comparing real-life societal norms to their fictional counterparts. The focus will mainly be on the introduction of the BL genre, the historical evolution of it, the commercial start of it, the main components that make up the genre, and why it is as popular as it is, a well as an examination of the culture surrounding the fans of the genre. -

View of the Study

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: March 2, 2005 I, MICHAEL DAVID FOWLER, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Piano It is entitled: Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Piano Media: Finding Parallelisms to Patterns in Japanese Culture. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: James Culley Kenneth Griffiths Frank Wienstock _______________________________ 2 Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Piano Media: Finding Parallelisms to Patterns in Japanese Culture A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS IN PIANO in the Keyboard Division, of the College Conservatory of Music 2005 by Michael D. Fowler Dip.Mus., University of Newcastle, 1994 B.Mus. (Hons), University of Newcastle, 1996 M.M. University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: James Culley 3 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the musical analysis of Toshi Ichiyanagi’s 1972 solo piano composition Piano Media, and an examination of musical processes and considerations that mirror and parallel patterns of traditional Japanese culture. Through brief studies of language construction, Zen, Pachinko and traditional aesthetics, analogies and references can be used to highlight congruent musical structures and predilections in Ichiyanagi’s work. The final goal is to define the work not only within musical terms of analysis, but also within a cultural context. 4 Copyright © 2004 by Michael Fowler All Rights Reserved 5 CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 9 Overview of the Study PART 1. SELECTED ELEMENTS OF JAPANESE CULTURE II. THE CULTIVATION OF THE JAPANESE SENSIBILITY THROUGH THE ARTS . -

How Law Made Silicon Valley

Emory Law Journal Volume 63 Issue 3 2014 How Law Made Silicon Valley Anupam Chander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Anupam Chander, How Law Made Silicon Valley, 63 Emory L. J. 639 (2014). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol63/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANDER GALLEYSPROOFS2 2/17/2014 9:02 AM HOW LAW MADE SILICON VALLEY Anupam Chander* ABSTRACT Explanations for the success of Silicon Valley focus on the confluence of capital and education. In this Article, I put forward a new explanation, one that better elucidates the rise of Silicon Valley as a global trader. Just as nineteenth-century American judges altered the common law in order to subsidize industrial development, American judges and legislators altered the law at the turn of the Millennium to promote the development of Internet enterprise. Europe and Asia, by contrast, imposed strict intermediary liability regimes, inflexible intellectual property rules, and strong privacy constraints, impeding local Internet entrepreneurs. This study challenges the conventional wisdom that holds that strong intellectual property rights undergird innovation. While American law favored both commerce and speech enabled by this new medium, European and Asian jurisdictions attended more to the risks to intellectual property rights holders and, to a lesser extent, ordinary individuals. -

Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation

Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation Tuomas Sibakov Master’s Thesis East Asian Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Helsinki November 2020 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Faculty of Humanities East Asian Studies Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track East Asian Studies Tekijä – Författare – Author Tuomas Valtteri Sibakov Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Imōto-Moe: Sexualized Relationships Between Brothers and Sisters in Japanese Animation Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Master’s Thesis year 83 November 2020 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract In this work I examine how imōto-moe, a recent trend in Japanese animation and manga in which incestual connotations and relationships between brothers and sisters is shown, contributes to the sexualization of girls in the Japanese society. This is done by analysing four different series from 2010s, in which incest is a major theme. The analysis is done using visual analysis. The study concludes that although the series can show sexualization of drawn underage girls, reading the works as if they would posit either real or fictional little sisters as sexual targets. Instead, the analysis suggests that following the narrative, the works should be read as fictional underage girls expressing a pure feelings and sexuality, unspoiled by adult corruption. To understand moe, it is necessary to understand the history of Japanese animation. Much of the genres, themes and styles in manga and anime are due to Tezuka Osamu, the “god of manga” and “god of animation”. From the 1950s, Tezuka was influenced by Disney and other western animators at the time. -

Master Keaton: Volume 10 Free

FREE MASTER KEATON: VOLUME 10 PDF Naoki Urasawa,Hokusei Katsushika | 322 pages | 06 Apr 2017 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421585260 | English | San Francisco, United States Baka-Updates Manga - Master Keaton Remaster Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Master Keaton, Vol. Master Keaton, Vol. Takashi Nagasaki. Hokusei Katsushika Creator. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Master Keaton: Kanzenban 5. Other Editions 5. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Master Keaton, Vol. Be the first to Master Keaton: Volume 10 a question about Master Keaton, Vol. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Master Keaton, Vol. Feb 15, Derek Royal rated it really liked it. Volume by volume, I'm making my way through Urasawa's Master Keaton series. A marked difference from his Monster is the episodic nature of this series. In the vast majority of its chapters, Keaton's adventures are stand-alone and can be appreciated outside of the context of the others. In some way, that's a strength of this title. On the other hand, I tend to appreciate more the longer-form stories involving Keaton, the ones that last two, three, or more segments. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

Aniplex of America to Release the Complete First Season of Silver Spoon on DVD

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 24, 2014 Aniplex of America to Release The Complete First Season of Silver Spoon on DVD ©Hiromu Arakawa, Shogakukan/EZONO Festa Executive Committee From the Author of the Hit Series Fullmetal Alchemist Comes a Story of Farm work, Friendship, and the Freshest Food! SANTA MONICA, CA (May 24, 2014) –Aniplex of America announced earlier today of their plans to release the first season of Silver Spoon in a complete DVD set on July 15th. Pre-orders for this product will begin on May 27th through official Aniplex of America retailers. Silver Spoon is an anime adaptation of the manga series originally created by author, Hiromu Arakawa (Fullmetal Alchemist), which has been awarded both the 5th Manga Taisho Award and the 58th Shogakukan Manga Award in 2012. The unique story follows Yugo Hachiken, a young man who decides to attend an agricultural high school in the countryside of Hokkaido prefecture in order to escape the academic pressures he had to live within the city. The series demonstrates how Yugo, who is initially burned-out, comes to see his life through a different light as he engages with his classmates and works with the animals on the farm at Oezo Agricutral High School a.k.a. Ezono. The anime series is directed by Tomohiko Ito, best known for his work with Sword Art Online, and the animation was produced by A-1 Pictures notable for their work on popular titles such as Sword Art Online, Magi: The Kingdom of Magic, Blue Exorcist, and Oreimo 2. The first season of Silver Spoon’s anime series began its simulcast schedule in July of last year. -

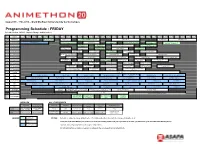

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

2021 I I Kataloğu

2021 İ İ KATALOĞU İ İ İ İ İ [email protected] www.ozhat.com [email protected] https://www.ozhat.com.tr Buttim İşmerkezi A Blok Kat:2 No:344 Osmangazi / BURSA YEDEK PARÇA KATALOĞUMUZ 3AAA 3D connexion 3M 3M Company 3Wave 4D Technology 555 Motors FLEXIBLE AUTOMATION AMiT, spol. s r.o. Aaeon AAF Aag Aalborg Instruments Aa Tech ABAC Abanaki Oil Skimmer Abax Abaxis Abbey ABB Jokab ABB SAGE AB C.A. ÖSTBERG ABC diesel ABCO Ab Connectors ABEL ABEL Piston pump ABEM Abex (Parker) Abicor Binzel Hetronic Ab Kihlstroms Manometerfabrik ABLE SYSTEMS abloy Abl Sursum Abm bvba pomac-lub-services sprl ABP INDUCTION Abracon A.B.S. Silo Absolute Process Instruments AB TRASMISSIONI Abus ACC Accel Accele Acco Acco Rexel ACCRETECH ACCU CODER ACCUCUTTER Accuenergy Accu-Lube Accumax ACCU-SORT AccuStandard Accustar Accu Tools Accuway ACDC Dynamics Acd Cryo Ac-Delco Ace Ace Controls Ace Laboratory Ace-mec Ace Pneumatic Ace Tool ACHENBACH Achilli s.r.l. ACI Ackrutat Acksys Acla Aclafrance Acm Acme Acme Electric ACMI AC Motoren ACOEM Acomel Acopian ACOPOS Acr Electronics Acrolon Acroprint Acs Control-System ACS CONTSYS Acson International Actaris [Itron] ACT ELECTRIC Actia Action Instruments (Eurotherm) ACT PRESSURE SWITCH Actreg Act Test Panels Acuangle Acuvim МAC Valves A&D Adalit Sadece yeni ve orijinal ürün satıyoruz! Firmamızın internet sitesinde ve katalogta gösterilen tüm markaların yetkili distribütör veya üretici temsilcisi olmayıp, bu sitede gösterilen Özel marka adları ve ticari markalar ilgili sahiplerinin mülkiyetindedir [email protected] https://www.ozhat.com.tr Buttim İşmerkezi A Blok Kat:2 No:344 Osmangazi / BURSA Adam Adamczewski Adams Armaturen Adams Lube Adams Rite Adani ADAN LTD Adaptall Adaptec Adc Adca Adda Adda Antriebstechnik Adder Technology ADDONICS. -

Rites of Blind Biwa Players

ASIA 2017; 71(2): 567–583 Saida Khalmirzaeva* Rites of Blind Biwa Players DOI 10.1515/asia-2017-0034 Abstract: Not much is known about the past activities of blind biwa players from Kyushu. During the twentieth century a number of researchers and folklorists, such as Tanabe Hisao, Kimura Yūshō,KimuraRirō,Nomura(Ga) Machiko, Narita Mamoru, Hyōdō Hiromi and Hugh de Ferranti, collected data on blind biwa players in various regions of Kyushu, made recordings of their performances and conducted detailed research on the history and nature of their tradition. However, despite these efforts to document and publicize the tradition of blind biwa players and its representatives and their repertory, it ended around the end of the twentieth century. The most extensively docu- mented individual was Yamashika Yoshiyuki 山鹿良之 (1901–1996), one of the last representatives of the tradition of blind biwa players, who was known among researchers and folklorists for his skill in performing and an abundant repertory that included rites and a great many tales. Yamashika was born in 1901 in a farmer family in Ōhara of Tamana District, the present-day Kobaru of Nankan, Kumamoto Prefecture. Yamashika lost the sight in his left eye at the age of four. At the age of twenty-two Yamashika apprenticed with a biwa player named Ezaki Shotarō 江崎初太郎 from Amakusa. From his teacher Yamashika learned such tales as Miyako Gassen Chikushi Kudari 都合戦筑紫 下り, Kikuchi Kuzure 菊池くづれ, Kugami Gassen くがみ合戦, Owari Sōdō 尾張 騒動, Sumidagawa 隅田川 and Mochi Gassen 餅合戦. After three years Yamashika returned home. He was not capable of doing much farm work because his eyesight had deteriorated further by then. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first.