General Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1-2 Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice Marc Buijnsters The various developments in doctrinal thought and practice during the Insei and Kamakura periods remain one of the most intensively researched fields in the study of Japanese Buddhism. Two of these developments con cern the attempts to restore the observance of traditional Buddhist ethics, and the problem of how Pure La n d tenets could be inserted into the esoteric teaching. A pivotal role in both developments has been attributed to the late-Heian monk Jichihan, who was lauded by the renowned Kegon scholar- monk Gydnen as “the restorer of the traditional precepts ” and patriarch of Japanese Pure La n d Buddhism.,’ At first glance, available sources such as Jichihan’s biograpmes hardly seem to justify these praises. Several newly discovered texts and a more extensive use of various historical sources, however, should make it possible to provide us with a much more accurate and complete picture of Jichihan’s contribution to the restoration and innovation of Buddhist practice. Keywords: Jichihan — esoteric Pure Land thousfht — Buddhist reform — Buddhist precepts As was n o t unusual in the late Heian period, the retired Regent- Chancellor Fujiwara no Tadazane 藤 原 忠 実 (1078-1162) renounced the world at the age of sixty-three and received his first Buddnist ordi nation, thus entering religious life. At tms ceremony the priest Jichi han officiated as Teacher of the Precepts (kaishi 戒自帀;Kofukuji ryaku 興福寺略年代記,Hoen 6/10/2). Fujiwara no Yorinaga 藤原頼長 (1120-11^)0), Tadazane^ son who was to be remembered as “Ih e Wicked Minister of the Left” for his role in the Hogen Insurrection (115bハ occasionally mentions in his diary that he had the same Jichi han perform esoteric rituals in order to recover from a chronic ill ness, achieve longevity,and extinguish his sins (Taiki 台gd Koji 1/8/6, 2/2/22; Ten,y6 1/6/10). -

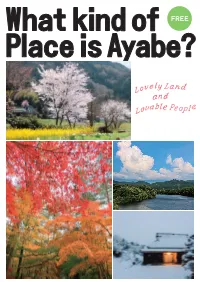

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

Noh Theater and Religion in Medieval Japan

Copyright 2016 Dunja Jelesijevic RITUALS OF THE ENCHANTED WORLD: NOH THEATER AND RELIGION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN BY DUNJA JELESIJEVIC DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in East Asian Languages and Cultures in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Elizabeth Oyler, Chair Associate Professor Brian Ruppert, Director of Research Associate Professor Alexander Mayer Professor Emeritus Ronald Toby Abstract This study explores of the religious underpinnings of medieval Noh theater and its operating as a form of ritual. As a multifaceted performance art and genre of literature, Noh is understood as having rich and diverse religious influences, but is often studied as a predominantly artistic and literary form that moved away from its religious/ritual origin. This study aims to recapture some of the Noh’s religious aura and reclaim its religious efficacy, by exploring the ways in which the art and performance of Noh contributed to broader religious contexts of medieval Japan. Chapter One, the Introduction, provides the background necessary to establish the context for analyzing a selection of Noh plays which serve as case studies of Noh’s religious and ritual functioning. Historical and cultural context of Noh for this study is set up as a medieval Japanese world view, which is an enchanted world with blurred boundaries between the visible and invisible world, human and non-human, sentient and non-sentient, enlightened and conditioned. The introduction traces the religious and ritual origins of Noh theater, and establishes the characteristics of the genre that make it possible for Noh to be offered up as an alternative to the mainstream ritual, and proposes an analysis of this ritual through dynamic and evolving schemes of ritualization and mythmaking, rather than ritual as a superimposed structure. -

Supernatural Elements in No Drama Setsuico

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN NO DRAMA \ SETSUICO ITO ProQuest Number: 10731611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731611 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Supernatural Elements in No Drama Abstract One of the most neglected areas of research in the field of NS drama is its use of supernatural elements, in particular the calling up of the spirit or ghost of a dead person which is found in a large number (more than half) of the No plays at present performed* In these 'spirit plays', the summoning of the spirit is typically done by a travelling priest (the waki)* He meets a local person (the mae-shite) who tells him the story for which the place is famous and then reappears in the second half of the.play.as the main person in the story( the nochi-shite ), now long since dead. This thesis sets out to show something of the circumstances from which this unique form of drama v/as developed. -

In Genji Monogatari Masako

01-大野 06.3.2 9:57 AM ページ1 “Monogatari” and “Old Monogatari” in Genji Monogatari Masako Ono What is curious about Genji monogatari 源氏物語 is that Murasaki Shikibu 紫式部 designates as“old”even those monogatari that were loved by the people in her age as the most fashionable and exciting ones. Her gesture to differentiate her own monogatari from old monogatari (mukashi monogatari 昔物語), however, does not effect what it purports, because the narrative of Genji continues and imitates the traditional pattern of old monogatari immediately after making a depreciatory com- ment on old monogatari. What I am going to observe is the deeper implication of this seeming paradox. I will investigate how Genji monogatari retroactively defines what old monogatari is by its paradoxical gesture of differentiating itself from and identifying itself with old monogatari. Monogatari gets defined when old mono- gatari is defined. In other words, monogatari as a genre does not present itself as monogatari, but as something different from old monogatari. I will argue that monogatari inheres something nostalgic in itself. We cannot reach the presence of monogatari except through old monogatari, because monogatari is constituted through its past. Monogatari is a genre nostalgically perceived. 1: Nostalgia for Mukashi Monogatari in Genji monogatari Genji monogatari constantly refers to old monogatari. As Kaoru 薫1 visits Uji 宇治 in the heavy rain and among the thick underbrush, not knowing that the 1 From his childhood, Kaoru has been bothered by the suspicion that Genji 源氏 might not be his real father. With his religious predilection, he is drawn toward the religious serenity of the Eighth Prince (Hachinomiya 八の宮), who, although born to a high- ranked nobility as a younger brother of Genji, has been embittered and tormented by a series of ill fortunes, and is determined to live a saint’s life. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Showa Age*

Klaus Antoni Universitdt Hamburg Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Showa Age* Abstract This article is concerned with a famous Japanese fairy tale, Momotaro, which was used during the war years in school readers as a primary part of nationalistic pro paganda. The tale and its central motif are analyzed and traced back through history to its earliest forms. Heroes from legend and history offered perfect identification patterns and images for the propagation of state ideals that were spread through education, the military, and war propaganda. Momotaro subtly- transmitted to young school pupils that which official Japan looked upon as the goal of its ideological education: through a fairy tale the gate to the “ Japanese spirit ” was opened. Key words: Momotaro — Japanese spirit — war propaganda Ryukyu Islands Asian Folklore Studies> Volume 50,1991:155-188. N a t io n a l is m a n d F o l k T r a d it io n in M o d e r n J a p a n F oundations of Japanese N ationalism APAN is a land rich in myths, legends, and fairy tales. It pos sesses a large store of traditional oral and literary folk literature, J which has not been accounted for or even recognized in the West. The very earliest traditional written historical documents contain narratives, themes, and motifs that express this rich tradition. Even though the Kojiki of the year 712, the oldest extant written source, was conceived of as a historical work at the time, it is a collection of pure myths, or at least the beginning portions are. -

2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

Yoko Tomiyasu 2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan 1 CONTENTS Biographical information .............................................................3 Statement ................................................................................4 Translation.............................................................................. 11 Bibliography and Awards .......................................................... 18 Five Important Titles with English text Mayu to Oni (Mayu & Ogree) ...................................................... 28 Bon maneki (Invitation to the Summer Festival of Bon) ......................... 46 Chiisana Suzuna hime (Suzuna the Little Mountain Godness) ................ 67 Nanoko sensei ga yatte kita (Nanako the Magical Teacher) ................. 74 Mujina tanteiktoku (The Mujina Ditective Agency) ........................... 100 2 © Yoko Tomiyasu © Kodansha Yoko Tomiyasu Born in Tokyo in 1959, Tomiyasu grew up listening to many stories filled with monsters and wonders, told by her grandmother and great aunts, who were all lovers of storytelling and mischief. At university she stud- ied the literature of the Heian period (the ancient Japanese era lasting from the 8th to 12 centuries AD). She was deeply attracted to stories of ghosts and ogres in Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), and fell more and more into the world of traditional folklore. She currently lives in Osaka with her husband and two sons. There was a long era of writing stories that I wanted to read for myself. The origin of my creativity is the desire to write about a wonderous world that children can walk into from their everyday life. I want to write about the strange and mysterious world that I have loved since I was a child. 3 STATEMENT Recommendation of Yoko Tomiyasu for the Hans Christian Andersen Award Akira Nogami editor/critic Yoko Tomiyasu is one of Japan’s most popular Pond).” One hundred copies were printed. It authors and has published more than 120 was 1977 and Tomiyasu was 18. -

2 Les Dragons De Natsukawa

CONCOURS CREATION 2020 THEME : Le confinement EXPRESSION LITTERAIRE Catégorie Adulte (+19ans) 2ème Prix [email protected] UFE ABU DHABI www.ufeabudhabi.com FREDERIC DUMASLes dragons de NatsukawaLES DRAGONS DE NATSUKAWA La Victoire c’est tomber sept fois, se relever huit… Proverbe japonais FREDERIC DUMAS LES DRAGONS DE NATSUKAWA Tokyo 30ème jour du confinement… Ça y est ! Je ne suis plus seule. Je ne pensais pas que ma façon de vivre, ma philosophie, pourrait irradier le monde aussi vite. Bon apparemment j’y suis pour rien et c’était pas vraiment voulu… C’est un virus qui a tout déclenché… un coronavirus… un abominable avorton acaryote, tout droit sorti d’un sordide marché putride, mêlant des animaux improbables tels que chauves-souris, pangolins et rats- musqués. Et voilà ! Tout le monde se confine… Les gens ont peur… moi j’avais déjà peur avant… Il faut dire que j’ai peur de presque tout… des gens surtout… je suis ochlophobe… pour moi la foule ça commence à deux… les grands espaces ne me font peur que parce que quelqu’un peut surgir… Alors j’évite, j’esquive, j’avorte, j’annihile toute possibilité d’une relation physique avant même qu’elle n’ait eu une chance de germer dans le monde des possibles. Mon monde c’est ma chambre, mon univers c’est mon ordinateur, mes dieux sont Osamu Tezuka et Satoshi Nakamoto et mon meilleur ami le distributeur automatique de soda en bas de mon immeuble… Je m’appelle Natsukawa Fujiwara, j’habite dans le quartier Hakihabara à Tokyo, j’ai vingt-cinq ans et je suis une hikikomori… Aujourd’hui c’est le 30eme jour de confinement pour toute la population.