Varieties of Cross-Class Coalitions in the Politics of Dualization: Insights from the Case of Vocational Training in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Is Who in Impeding Climate Protection

Who is Who in Impeding Climate Protection Links between politics and the energy industry The short route to climate collapse The UK meteorological offi ce forecast at the very beginning of the year that 2007 would be the warmest year since weather records began being made. The scientists there estimated that the global average temperature would be 0.54 degrees above the 14 degree average experienced over many years. The record so far, an average of 14.52 degrees, is held by 1998. 2005, which was similarly warm, went into the meteorologists’ record books on reaching an average of 14.65 degrees in the northern hemisphere. Findings made by the German meteorological service also confi rm the atmosphere to be warming. Shortly before the beginning of 2007 the service reported that the year 2006 had been one of the warmest years since weather records began being made in 1901, and the month of July had been the hottest ever since then. An average of 9.5 degrees was 1.3 degrees Celsius above the long-term average of 8.2 degrees. International climate experts are agreed that the global rise in temperature must stay below two degrees Celsius if the effects of climate change are to remain controllable. But the time corridor for the effective reduction of greenhouse gases damaging to the climate is getting narrower and narrower. In the last century already the Earth’s average temperature rose by 0.8 degrees. The experts in the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change anticipate a further rise of up to 6.4 degrees by 2100. -

Die August-Ausgabe 2005 Des Niedersachsen Vorwärts

SPDN_Vorwaerts_0805_3a_RZ 08.08.2005 20:09 Uhr Seite 3 √NIEDERSACHSEN AUGUST: 2005 einwärts: Warum es sich zu kämpfen lohnt Mit Recht hat die CDU so ihre Probleme. Dass der für VON WOLFGANG JÜTTNER VORSIT- Oder darum, ob neue Kern- den Schutz der Niedersäch- ZENDER DER NIEDERSACHSEN-SPD kraftwerke gebaut werden sischen Verfassung zustän- und Niedersachsen zum dige Minister Uwe Schüne- Bis zum 18. September ist es Atomklo für ganz Deutsch- mann vom Bundesverfas- nicht mehr lang, die heiße land wird. Und um die Fra- sungsgericht zur Wahrung Wahlkampfphase hat ge, ob Arbeitnehmerinnen von Recht und Ordnung längst begonnen. Wir Sozi- undArbeitnehmer dem glo- verpflichtet werden muss- aldemokratinnen und Sozi- balen Kapitalismus schutz- te, markiert den einst- aldemokraten haben noch los ausgeliefert sein sollen. weiligen Tiefstand nieder- eine Menge aufzuholen. Wir Sozialdemokratin- sächsischer Regierungsge- Aber in den vergangenen nen und Sozialdemokraten schichte. Tagen hat sich gezeigt: Die haben allen Grund stolz zu Niedersachsens Minis- CDU wird nervös–zu Recht. sein auf das, was die Bundes- terpräsident Christian Erst versuchte Angela Mer- regierung in den vergange- Wulff glänzt einmal mehr kel beim TV-Duell zu knei- nen sieben Jahren erreicht durch Sprachlosigkeit. Das fen, dann verwechselte sie hat. Wir haben Deutsch- ist bezeichnend für diesen brutto und netto und ließ land aus der bleiernen Kohl- Messias des Mittelmaßes. sich immer neue Entschul- Zeit herausgeführt und an- Wulff handelt nach der digungen für ihre zahlrei- gepackt, was Schwarz-Gelb Devise: Eiskalt lächeln, nur chen Patzer einfallen. Es 16 Jahre lang ausgesessen nicht anecken und die Drek- wird immer deutlicher: hat. Wir haben die Sozial- ksarbeit anderen überlas- Frau Merkel kann es nicht. -

EUSA Boyleschuenemann April 15

The Malleable Politics of Activation Reform: the‘Hartz’ Reforms in Comparative Perspective Nigel Boyle[[email protected]] and Wolf Schünemann [[email protected]] Paper for 2009 EUSA Biennial Conference, April 25, Los Angeles. Abstract In this paper we compare the Hartz reforms in Germany with three other major labor market activation reforms carried out by center-left governments. Two of the cases, Britain and Germany, involved radically neoliberal “mandatory” activation policies, whereas in the Netherlands and Ireland radical activation change took a very different “enabling” form. Two of the cases, Ireland and Germany, were path deviant, Britain and the Netherlands were path dependent. We explain why Germany underwent “mandatory” and path deviant activation by focusing on two features of the policy discourse. First, the coordinative (or elite level) discourse was “ensilaged” sealing policy formation off from dissenting actors and, until belatedly unwrapped for enactment, from the wider communicative (legitimating) discourse. This is what the British and German cases had in common and the result was reform that viewed long term unemployment as personal failure rather than market failure. Second, although the German policy-making system lacked the “authoritative” features that facilitated reform in the British case, and the Irish policy- making system lacked the “reflexive” mechanisms that facilitated reform in the Dutch case, in both Germany and Ireland the communicative discourses were reshaped by novel institutional vehicles (the Hartz Commission in the German case, FÁS in the Irish case) that served to fundamentally alter system- constitutive perceptions about policy. In the Irish and German cases “government by commission” created a realignment of advocacy coalitions with one coalition acquiring a new, ideologically-dominant and path deviating narrative. -

Political Scandals, Newspapers, and the Election Cycle

Political Scandals, Newspapers, and the Election Cycle Marcel Garz Jil Sörensen Jönköping University Hamburg Media School April 2019 We thank participants at the 2015 Economics of Media Bias Workshop, members of the eponymous research network, and seminar participants at the University of Hamburg for helpful comments and suggestions. We are grateful to Spiegel Publishing for access to its news archive. Daniel Czwalinna, Jana Kitzinger, Henning Meyfahrt, Fabian Mrongowius, Ulrike Otto, and Nadine Weiss provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Hamburg Media School. Corresponding author: Jil Sörensen, Hamburg Media School, Finkenau 35, 22081 Hamburg, Germany. Phone: + 49 40 413468 72, fax: +49 40 413468 10, email: [email protected] Abstract Election outcomes are often influenced by political scandal. While a scandal usually has negative consequences for the ones being accused of a transgression, political opponents and even media outlets may benefit. Anecdotal evidence suggests that certain scandals could be orchestrated, especially if they are reported right before an election. This study examines the timing of news coverage of political scandals relative to the national election cycle in Germany. Using data from electronic newspaper archives, we document a positive and highly significant relationship between coverage of government scandals and the election cycle. On average, one additional month closer to an election increases the amount of scandal coverage by 1.3%, which is equivalent to an 62% difference in coverage between the first and the last month of a four- year cycle. We provide suggestive evidence that this pattern can be explained by political motives of the actors involved in the production of scandal, rather than business motives by the newspapers. -

Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff FDP � 5804 C Anlage 1 Dr

Plenarprotokoll 12/68 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 68. Sitzung Bonn, Freitag, den 13. Dezember 1991 Inhalt: Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 13: des Rates über die Überwachung und Abgabe einer Erklärung der Bundesre- Kontrolle der Großkredite von Kreditin- gierung zu den Ergebnissen des Europäi- stituten (Drucksachen 12/849 Nr. 2.1, schen Rates in Maastricht 12/1809) 5833 C Dr. Helmut Kohl, Bundeskanzler 5797 B Nächste Sitzung 5833 D Ingrid Matthäus-Maier SPD 5803 B Berichtigung 5833 Stefan Schwarz CDU/CSU 5804 B Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff FDP 5804 C Anlage 1 Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble CDU/CSU 5806D Liste der entschuldigten Abgeordneten 5835* A Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff FDP 5810 D Dr. Hans Modrow PDS/Linke Liste 5813 A Anlage 2 Gerd Poppe Bündnis 90/GRÜNE 5815 B Zu Protokoll gegebene Reden zu Tagesord- Dr. Theodor Waigel, Bundesminister BMF 5817 B nungspunkt 12 und Zusatztagesordnungs- Dr. Norbert Wieczorek SPD 5819 D punkt 12 (Antrag betr. Sofortige Auflösung Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Bundesminister des „Koordinierungsausschusses Wehrmate- AA 5822 C rial fremder Staaten" des Bundesnachrich- tendienstes und der Bundeswehr und Antrag Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul SPD 5826 A betr. Parlamentarische Kontrolle der Auflö- Peter Kittelmann CDU/CSU 5827 B sung der NVA) Dr. Kurt Faltlhauser CDU/CSU 5828 D Thomas Kossendey CDU/CSU 5836* A Wolfgang Clement, Minister des Landes Gernot Erler SPD 5836* C Nordrhein-Westfalen 5830 C Jürgen Koppelin FDP 5837* C Dr. Cornelie von Teichman FDP 5832 B Dr. Dagmar Enkelmann PDS/Linke Liste 5838* B Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 14: Willy Wimmer, Parl. Staatssekretär BMVg 5838* D Beratung der Beschlußempfehlung und des Berichts des Finanzausschusses zu Anlage 3 der Unterrichtung durch die Bundesre- gierung: Vorschlag für eine Richtlinie Amtliche Mitteilungen 5839* D Deutscher Bundestag — 12. -

Pressespiegel

Pressespiegel vom Mittwoch, den 27.02.2008 Berichterstattung Demografiefeste Unternehmen 3 01.03.2008 Personal - Zeitschrift für Human Resource Management Nicht über alternde Belegschalten nachzudenken/ ist ein Risiko für Unternehmen und Beschäftigte. ... Deutsche Firmen auf alternde Bevölkerung kaum vorbereitet 6 27.02.2008 Die Welt DÜSSELDORF- Deutschlands Unternehmen sind schlecht vorbereitet auf den einsetzenden demographischen Wandel. ... Ein Fitness-Index(DFX) prüft nun auf fünf Gebieten die Reaktion der Unternehmen darauf: Aufstiegsmöglichkeiten, lebenslanges Lernen, Wissensmanagement, Gesundheitsmanagement und Altersvielfalt. ... "Ich bin Sozialdemokrat, ich bleibe Sozialdemokrat" 7 27.02.2008 Die Welt ... DÜSSELDORF- Wolfgang Clement spricht über den"demografischen Fitness- Index". ... 14 Stunden vor Clements Pressekonferenz sind Delegierte am Montagabend zu einem Parteitag in Bochum-Wattenscheid zusammengekommen. "Von Bali bis Bochum", lautet das Thema, aber es geht nicht um Urlaub, sondern um Klimaschutz. Deshalb ist auch Matthias Machnig gekommen, Staatssekretär im Bundesumweltministerium und ehemaliger SPD-Wahlkampfmanager. ... Clement: Ich bin und bleibe Sozialdemokrat 9 27.02.2008 Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung ... Der frühere Bundeswirtschaftsminister und Ministerpräsident in Nordrhein- Westfalen,Clement(unser Bild), will sich nicht einfach aus der SPD hinauswerfen lassen." ... Am Montagabend hatten etliche SPD Mitglieder auf einem Unterbezirksparteitag in Bochum, wo Clement seit fast vierzig Jahren SPD-Mitglied ist, ihren -

Olaf Sundermeyer Der Pott Warum Das Ruhrgebiet Den Bundeskanzler Bestimmt Und Schalke Ganz Sicher Deutscher Meister Wird

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Olaf Sundermeyer Der Pott Warum das Ruhrgebiet den Bundeskanzler bestimmt und Schalke ganz sicher Deutscher Meister wird 238 Seiten, Paperback ISBN: 978-3-406-59134-1 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München metropolig Eine eindeutige Antwort auf die Frage, ob das Ruhrgebiet nun eine Metropole ist, kann ich Ihnen nicht geben. Dafür lasse ich auf einer Reise durch den Pott einige Menschen zu Wort kommen, die sich dar- über Gedanken gemacht haben. Aber vor allem zeige ich Ihnen ei- niges von dem, was das Ruhrgebiet heute ausmacht. Natürlich nur in Ausschnitten. Sonst hätte ich mich zusätzlich an einigen Samstagen in Baumärkten herumtreiben müssen, in der Autowaschanlage «Wascharena» in Gelsenkirchen, auf Ramschmärkten vor Möbelhäu- sern in Bottrop oder in den Fitnessstudios zwischen Oberhausen und Hamm. Aber Autowaschen fahren Sie vermutlich selbst, einkaufen auch. Außerdem war ich zu Fuß unterwegs, mit dem Fahrrad und mit Bus und Bahn. Ich wollte nämlich nah dran sein – das Ruhrgebiet ver- messen, wie man neuerdings sagt. Welche Ausmaße hat es? Wie viele Menschen leben dort? Welche Städte gehören eigentlich dazu? Wen man auch fragt, die Antworten fallen immer unterschiedlich aus. Zu- letzt wurde politisch entschieden, dass sich das Ruhrgebiet auf 53 Städte und Gemeinden ausdehnt und deshalb etwa 5,3 Millionen Menschen hier leben. Allerdings stehen da Orte mit auf der Liste, bei denen sich der Herner oder Wittener fragt: «Wat soll dat denn?» Aber wer weiß außerhalb, also in Restdeutschland, schon, dass in Dortmund mehr Menschen leben als in Düsseldorf, Stuttgart oder Leipzig? Dass Berlin und Hamburg zusammengenommen weniger 9 Einwohner haben als der Pott und erst recht viel weniger Fläche. -

Editorial Cancún Und Die Folgen Kultur-Mensch

English + Supplement Zeitung des Deutschen Kulturrates Nr. 05/03 • November - Dezember 2003 www.kulturrat.de 3,00 € • ISSN 1619-4217 • B 58 662 Kulturpolitik in NRW Gemeindefinanzreform GATS Bildungsreform The English Supplement Die Kürzungspläne des Landes Die Städte und Gemeinden stehen Bundeswirtschaftsminister Clement Wie eine Zusammenarbeit von Focus GATS and Cancún: what NRW bedeuten auch für den Kul- vor dem finanziellen Kollaps. Der eröffnet mit seinem Leitartikel die Schule und außerschulischen Ein- consequences for cultural policy? turbereich massive Einschnitte. Stellvertretende Präsident des Nach-Cancún-Betrachtungen. Max richtungen aussehen könnte be- Assessments by Economic Affairs Minister Vesper erläutert sein Vor- Deutschen Städtetags Herbert Fuchs und Fritz Pleiten fordern schreibt Ministerin Schäfer aus Minister Wolfgang Clement, by gehen. Kulturdezernenten und Schmalstieg stellt die Forderungen Ausnahmeregelungen für die Kul- NRW. Der Präsident der Universität Culture Committee Chairwoman Leiter von Kulturinstitutionen der Städte und Gemeinden an eine tur bei den GATS-Verhandlungen. der Künste benennt die Besonder- Monika Griefahn, by professio- kommen zu Wort. Der Vorsitzende Gemeindefinanzreform vor. Iris Die Ergebnisse der Verhandlungs- heiten künstlerischer Ausbildung nals and civil society. Also: out- des Kulturrats-NRW stellt sich den Magdowski erinnert an Impulse aus runde in Cancún werden vorge- und leitet Forderungen für die Zu- look on German Foreign Cultural Fragen von puk. der kommunalen Kulturpolitik. stellt. kunft der Kunsthochschulen ab. Policy. Seiten 2 - 5 Seiten 11 - 13 Seiten 1, 16 - 19 Seiten 24 - 26 Pages 7 - 10 Editorial Cancún und die Folgen Feuerwehr Zur Liberalisierung des internationalen Dienstleistungshandels • Von Wolfgang Clement s brennt an allen Ecken im Kul- gezwungen, gerade bei der ver- Das vorzeitige Ende der WTO-Minis- WTO-Entscheidungsprozess ver- selbereichen wie Finanz- und Trans- Eturland Deutschland. -

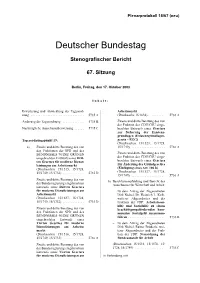

Plenarprotokoll 15/67(Neu)

Plenarprotokoll 15/67 (neu) Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 67. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 17. Oktober 2003 Inhalt: Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Arbeitsmarkt nung . 5735 A (Drucksache 15/1638) . 5736 A Änderung der Tagesordnung . 5735 B – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von der Fraktion der CDU/CSU einge- Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 5735 C brachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Sicherung der Existenz- grundlagen (Existenzgrundlagen- Tagesordnungspunkt 19: gesetz – EGG) (Drucksachen 15/1523, 15/1728, a) – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von 15/1749) . 5736 A den Fraktionen der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/DIE GRÜNEN – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Drit- der Fraktion der CDU/CSU einge- ten Gesetzes für moderne Dienst- brachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes leistungen am Arbeitsmarkt zur Änderung des Grundgesetzes (Drucksachen 15/1515, 15/1728, (Einfügung eines Art. 106 b) 15/1749, 15/1732) . 5735 D (Drucksachen 15/1527, 15/1728, 15/1749) . 5736 A – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von b) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des der Bundesregierung eingebrachten Ausschusses für Wirtschaft und Arbeit Entwurfs eines Dritten Gesetzes für moderne Dienstleistungen am – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Arbeitsmarkt Dirk Niebel, Dr. Heinrich L. Kolb, (Drucksachen 15/1637, 15/1728, weiterer Abgeordneter und der 15/1749, 15/1732) . 5735 D Fraktion der FDP:Arbeitslosen- hilfe und Sozialhilfe zu einem – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von beschäftigungsfördernden kom- den Fraktionen der SPD und des munalen Sozialgeld zusammen- BÜNDNISSES 90/DIE GRÜNEN führen . 5736 B eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Vierten Gesetzes für moderne – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dienstleistungen am Arbeits- Dirk Niebel, Rainer Brüderle, wei- markt terer Abgeordneter und der Frak- (Drucksachen 15/1516, 15/1728, tion der FDP:Neuordnung der 15/1749, 15/1733) . -

WOLFGANG CLEMENT 80 Jahre … … Und Kein Bisschen Leise R

WOLFGANG CLEMENT 80 Jahre … … und kein bisschen leise r WOLFGANG CLEMENT 80 Jahre – und kein bisschen leiser INHALT 7 | Vorwort von Dr. Rainer Dulger 9 | Peter Altmaier: Wolfgang Clement gilt mein großer Dank und Respekt 12 | Armin Laschet: Sich Zeit lassen – das ist Wolfgang Clement nicht 15 | Georg Wilhelm Adamowitsch: In Dankbarkeit und Freundschaft 19 | Prof. Dr. Ursula Engelen-Kefer: Ein harter Verhandler und verlässlicher Mitstreiter 22 | Sigmar Gabriel: Streitbar und doch verletzlich. Sozialdemokrat bis heute! 27 | Heike Göbel: Mit Marktkompass 30 | Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg: Das Gesicht 33 | Prof. Bodo Hombach: Fester Blick zum Horizont 36 | Prof. Dr. Dr. Otmar Issing: Ein Kämpfer für die Soziale Marktwirtschaft 39 | Arndt G. Kirchhoff: Bochumer, Journalist, Politiker, Marktwirtschaftler – ein Leben mit aufrechtem Gang auf klarem Kurs 42 | Ingo Kramer: Einem Original der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft zum Achtzigsten 45 | Christian Lindner: Von seinen Reformen profitieren wir noch heute 48 | Friedrich Merz: Wirtschafts- und Arbeitsmarktpolitik als Einheit denken 52 | Friedhelm Ost: Mit Optimismus in die Zukunft 55 | Prof. Dr. Andreas Pinkwart: Konsequent auf Modernisierungskurs 58 | Harald Schartau: Stillstand heißt Rückschritt – Handeln statt Abwarten 5 | 61 | Rezzo Schlauch: Ganz unter uns, Wolfgang Clement: Danke 64 | Prof. Hans-Werner Sinn: Ein grandioser Reform-Erfolg eines sozialdemokratischen Ministers 68 | Peer Steinbrück: Marathon Man 72 | Edmund Stoiber: Ein Mitstreiter für wirtschaftliche Reformen und Innovationen 75 | Dr. Michael Vesper: Ein Freund wird 80 79 | Ursula Weidenfeld: Die Glorreichen Vier 82 | Frank-Jürgen Weise: Führungswille, Beharrlichkeit und konsequente Umsetzung 84 | Oliver Zander: Wolfgang Clement, der ausgleichende Tarifpolitiker 87 | Die Karikaturisten 88 | Impressum, Fotonachweis | 6 VORWORT von Dr. Rainer Dulger Essen, was gar ist, trinken, was klar ist, reden, was wahr ist. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Plenarprotokoll 15/22 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 22. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 30. Januar 2003 Inhalt: Nachträgliche Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 3: des Bundesministers Dr. Peter Struck sowie des Abgeordneten Norbert Königshofen . 1665 A Antrag der Abgeordneten Rainer Brüderle, Dr. Hermann Otto Solms, weiterer Abge- Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag des Abgeord- ordneter und der Fraktion der FDP: Neue neten Wolfgang Spanier . 1665 A Chancen für den Mittelstand – Rahmen- Erweiterung der Mitgliederzahl im Ausschuss bedingungen verbessern statt Förder- für Kultur und Medien . 1665 A dschungel ausweiten (Drucksache 15/357) . 1666 C Wiederwahl der Abgeordneten Ulrike Poppe als Mitglied des Beirats nach § 39 des Stasi- Wolfgang Clement, Bundesminister BMWA 1666 D Unterlagen-Gesetzes . 1665 B Friedrich Merz CDU/CSU . 1670 C Festlegung der Zahl der Mitglieder des Euro- Fritz Kuhn BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN . 1674 A päischen Parlaments, die an den Sitzungen des Rainer Brüderle FDP . 1677 A Ausschusses für die Angelegenheiten der Euro- päischen Union teilnehmen können . 1665 B Klaus Brandner SPD . 1679 B Erweiterung der Tagesordnung . 1665 B Dagmar Wöhrl CDU/CSU . 1681 D Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen . 1666 A Werner Schulz (Berlin) BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN . 1684 A Gudrun Kopp FDP . 1685 D Tagesordnungspunkt 3: Dr. Gesine Lötzsch fraktionslos . 1687 B Antrag der Fraktionen der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/DIE GRÜNEN: Offen- Christian Lange (Backnang) SPD . 1688 A sive für den Mittelstand Laurenz Meyer (Hamm) CDU/CSU . 1690 A (Drucksache 15/351) . 1666 B Dr. Sigrid Skarpelis-Sperk SPD . 1692 A in Verbindung mit Hartmut Schauerte CDU/CSU . 1694 B Reinhard Schultz (Everswinkel) SPD . 1696 D Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 2: Alexander Dobrindt CDU/CSU . -

Hans-Werner Sinn Und 25 Jahre Deutsche Wirtschaftspolitik

SINN HANS-WERNER UND 25 JAHRE DEUTSCHE WIRTSCHAFTSPOLITIK HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GABRIEL FELBERMAYR | MEINHARD KNOCHE | LUDGER WÖßMANN HANS-WERNER SINN UND 25 JAHRE DEUTSCHE WIRTSCHAFTSPOLITIK HANS-WERNER SINN UND 25 JAHRE DEUTSCHE WIRTSCHAFTSPOLITIK Herausgegeben von Gabriel Felbermayr | Meinhard Knoche | Ludger Wößmann INHALT VORWORT 10 1 VOM LINKEN ZUM LIBERALEN : Hans-Werner Sinn und die deutsche Wirtschaftspolitik 15 LUDGER WÖSSMANN : Einleitung 16 HORST SEEHOFER : Soziale Marktwirtschaft – ein Erfolgsmodell für Bayern und Deutschland 18 WOLFGANG CLEMENT : Ein Mahner aus Prinzip 20 REINHARD KARDINAL MARX : Leitbild Chancengerechtigkeit 22 ULRICH GRILLO : Der Ökonomie-Erklärer – von A wie Arbeitsmarkt bis Z wie Zuwanderung 24 ROLAND BERGER : Hans-Werner Sinn: Volkswirt, Kommunikator, Manager 26 WOLFGANG FRANZ : Die Eiger-Nordwand und der Kombilohn: eine Reminiszenz 28 EDMUND PHELPS : Hans-Werner Sinn und Deutschlands natürliche Arbeitslosenrate 30 JAMES POTERBA : Rentenreform: Hans-Werners Forschung und politischer Einfluss 32 ASSAF RAZIN : Über den Jungen, den Politökonomen, den Unternehmer und den Freund 34 CARL CHRISTIAN VON WEIZSÄCKER : Hans-Werner Sinns Habilitationsschrift 36 ROLAND TICHY : Zwischen Sinn-Gap und Target-Falle gebofingert 38 KAI DIEKMANN : 25 Gründe, warum Hans-Werner Sinn als ifo-Präsident fehlen wird 41 2 KALTSTART : Hans-Werner Sinn und die Wiedervereinigung 47 MARCEL THUM : Einleitung 48 GEORG MILBRADT : Vereinigung ohne wirtschaftlichen Kompass 50 INHALT MARC BEISE : Der Trabi-Mann 52 4 MICHAEL C. BURDA : Die