Full Text In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Román Avantgárdkutatás Új Hulláma (Társas Esztétikák)

TÁRSAS ESZTÉTIKÁK 113 BALÁZS IMRE JÓZSEF A ROMÁN AVANTGÁRDKUTATÁS ÚJ HULLÁMA Popescu, Morar, Cernat, Drogoreanu, Gulea A megpezsdült román avantgárdku- történeti-irányzati összefüggések kerül- tatásnak elsõsorban a problémafelvetése- tek szóba, illetve az avantgárd specifikus it, téziseit kell feltérképezni ahhoz, hogy mûfaja, a manifesztum vált igen gyakran az újabb publikációk súlyát megállapít- az értelmezések kísérõjévé-kiindulópont- hassuk. Elsõ látásra is szembeötlõ, hogy jává. Pop mûközpontú, költõi motívumo- növekedett az átfogó, monografikus fel- kat érzékenyen követõ értelmezései nagy dolgozások száma 2000 után. Ráadásul természetességgel nõttek a késõbbiekben egy új, a hatvanas-hetvenes években szü- monografikus feldolgozásokká, amelyek letett kutatógeneráció lendületes bekap- ugyanazt a szempontrendszert alkalmaz- csolódásával is számolni lehet ezen a te- ták Lucian Blaga, Ilarie Voronca vagy rületen: Simona Popescu (sz. 1965), Gellu Naum életmûvének végigkövetése Ovidiu Morar (1966), Paul Cernat (1972), során. A Pop-féle paradigma természetes Emilia Drogoreanu (1977), illetve Dan és zsigeri ellenreakciót jelentett a korábbi Gulea (1977) egyaránt több könyvvel, túlpolitizált értelmezésekhez képest, közleménnyel járult hozzá a téma feldol- amelyek magát az avantgárdot is tévút- gozásához. A kérdés tehát az, milyen új nak, dekadens maradványnak tekintették szempontokat, megközelítésmódokat ér- (akárcsak a környezõ országok irodalom- hetünk tetten mûködés közben a közel- történetei), és leginkább az osztályharcos múltban színre -

Ironim Muntean Ion Todor

Ironim Muntean Ion Todor o n ■.000 Ediția a IV-a revăzută și adăugită Editura Alba lulia - 2019 Ironim Muntean Ion Todor Liceeni... odinioară Descrierea CIP a Biblotccii Naționale a României MUNTEAN, IRONIM Liceeni... odinioară / Ironim Muntean, Ion Todor; Ediție revăzută și adăugită / Cluj-Napoca: Grinta, 2011 ISBN 978-973-126-330-4 Tipărirea volumului finanțată de Opticline Alba lulia REDACTOR DE CARTE: Ion Alexandru Aldea Ironim Muntean Ion Todor Liceeni... odinioară Ediție revăzută și adăugită COLf;G?J; .HOREA. Ș| i ALBA MJA i Nr înv -^0^- Alba lulia 2019 PREFAȚĂ Autorii acestei cărți, Ironim Muntean și ion Todor mi-au fost colegi de facultate la Filologia clujeană, între anii 1960-1965 ai veacului încheiat. A fost o promoție numeroasă, din care dacă nu au ieșit personalități proeminente ale scrisului românesc contemporan, s-au afirmat destui ca remarcabili profesori secundari. Ironim Muntean și Ion Todor veneau din Alba lulia, capitala Marii Uniri, vechiul Bălgrad al începuturilor de scris românesc, absolvenți ai Liceului „Horia, Cloșca și Crișan”, care până după al doilea război mondial, purta numele gloriosului unificator de țară Mihai Viteazul. După absolvirea facultății nu s-au limitat ca mulți dascăli de literatura română, numai la activitatea catedratică, înțelegând scrisul didactic sau literar ca o completare firească a muncii la clasă. După ani și ani au ajuns profesori chiar în orașul în care absolviseră liceul, unul dintre ei, Ironim Muntean chiar la liceul „Horia, Cloșca și Crișan”, al cărui eminent absolvent fusese în urmă cu o jumătate de secol. Ambii au înțeles că este o datorie profesională, dar și de conștiință morală și patriotică studierea și punerea în lumină, sub riguros raport documentar, a tradițiilor istorice și liceale, pe care colegii le pot integra în lecțiile de istorie sau de literatură. -

Rez Eng Postescu

RETROVERSIUNE Emil Giurgiuca - Monografie Unquestionably, those who know the literary life from Transylvania, as little as possible, will not consider a futile effort to remove a writer from the undeserved shadow where the history placed him. Emil Giurca’s cultural activity, because about him we are talking about, is a significant “brick” from the wall which was created along with the vast process of clarifying the literary and spiritual Romanian literature and culture. Creator of literature, respected educator, he was in the same time an important fighter for national ideal but also a great entertainer, a cultural advisor to generations of writers from the interwar and postwar period. As many researchers of the aesthetic values observed, it seems that in any literature are important writers, widely recognized from the valuable point of view “as others who fall slightly below, but on different places in the hierarchy of values, enriching and diversifying artistic landscape from their period of time”1. Originally poet from his homeland, as Dumitru Micu noticed in “Romanian Literary History”, he became later the national poet of the whole national space, Emil Giurca cannot easily be integrated in any current or cannot be said that he belongs to any literary school and “if he installed in the classical formula, adopted by traditionalists (as Ion Barbu, a Paul Valery writer), he did it of course, because this formula and only it suited to his sensibility”2, Dumitru Micu said. Each poem in consistent with the requirements of the art is organize by an act of inner balance, a sense of the extent of composition; this is what we call Emil Giurca’s modernism. -

68 De Ani De La Proclamarea Independenţei Statului Israel

F.C.E.R. – Reuniunea Comună a Consiliului de Conducere şi Adunării Generale PAG. 3, 4, 5 PUBLICAŢIE A FEDERAŢIEI COMUNITĂŢILOR EVREIEŞTI DIN ROMÂNIA Eveniment omagial la Camera Deputaţilor ANUL LVI = NR. 472-473 (1272-1273) = 1 – 31 MAI 2016 =23 NISAN – 23 IYAR 5776 = 28 PAGINI – 3 LEI PAG. 18 Comemorări PAG. 7 68 de ani de la proclamarea de Iom HaŞoah Independenţei Statului Israel şi Iom HaZikaron Istoria limbii ebraice Pe 15 mai, Sinagoga Mare din Bu- cureşti a găzduit o pasionantă expunere susţinută de prof. Mireille Hadass Lebel despre cartea sa „Ebraica: 3000 de ani de istorie”. Autoarea a venit la Bucureşti la sugestia prof. Carol Iancu, prezent de asemenea la manifestare, alături de un numeros public şi de conducerea F.C.E.R. şi a C.E.B. Vom reveni în numărul viitor. Podurile Toleranţei ediţia a III-a PAG. 15, 16, 17 Comemorarea Reginei-Mamă Elena la Templul Coral din Bucureşti PAG. 13 Dr. Aurel Vainer la emisiunea „Jocuri de putere” (Realitatea TV) PAG. 9,10 Legislaţie reparatorie pentru cei care au suferit în Holocaust După cum am menţionat şi în numă- cadrul Grupului Parlamentar al Minorită- Un alt element de noutate şi cu un tuirea Proprietăţilor va putea analiza rul precedent al „Realităţii Evreieşti”, ţilor Naţionale. Propunerile au fost votate caracter reparatoriu este faptul că cere- soluţionarea unui număr important de deputatul F.C.E.R., dr. Aurel Vainer, a în plen cu o mare susţinere din partea rile pentru restituirea proprietăţilor for- cereri, formulate de Fundaţia Caritatea, promovat la Parlament, împreună cu întregului arc politic. -

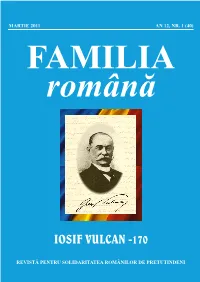

Iosif Vulcan -170

MARTIE 2011 AN 12, NR. 1 (40) FAMILIA română IOSIF VULCAN -170 REVISTĂ PENTRU SOLIDARITATEA ROMÂNILOR DE PRETUTINDENI (1) (2) (4) (5) (3) (7) (6) (8) (9) 1. Bust în Oradea, de Iosif Fekete (1964), 2.-4. Portret şi bust Iosif Vulcan, Colegiul Naţional „Iosif Vulcan” Oradea, 3. Medalie din bronz; 5. Copertă revista „Iosif Vulcan”, Cringila, Australia; 6.-7. Afişul unui spectacol şi copertă CD multimedia produs de Rock Filarmonica Oradea; 8. Piatra funerară în cimitirul din Oradea; 9. Muzeul memorial „Iosif Vulcan”, Oradea. str. „Iosif Vulcan” nr. 16. MARTIE 2011 BAIA MARE FAMILIA ROMÂNÃ REVISTÃ TRIMESTRIALÃ DE CULTURÃ ªI CREDINÞÃ ROMÂNEASCÃ Editori: Consiliul Judeþean Maramureº, Biblioteca Judeþeanã „Petre Dulfu” Baia Mare ºi Asociaþia Culturalã „Familia românã” Di rec tor fondator: Dr. Constantin MÃLINAª Di rec tor executiv - re dac tor ºef: Dr. Teodor ARDELEAN Re dac tor ºef adjunct: Prof. Ioana PETREUª Secretar de redacþie: Anca GOJA COLEGIUL DE REDACÞIE Hermina Anghelescu (Detroit, SUA) 6 Vadim Bacinschi (Odesa) 6 Vasile Barbu (Uzdin, Serbia) 6 6 Ion M. Botoº (Apºa de Jos, Ucraina) 6 Florica Bud 6 Sanda Ciorba (Algarve, Portugalia) 6 Eugen Cojocaru (Stuttgart, Germania) 6 Flavia Cosma (To ronto, Can ada) 6 Cornel Cotuþiu 6 Nicolae Felecan 6 Mirel Giurgiu (Frankenthal, Germania) 6 Sãluc Horvat 6 Ion Huzãu (Slatina, Ucraina) 6 Cãtãlina Iliescu (Alicante, Spania) 6 Lidia Kulikovski (Chiºinãu) 6 Natalia Lazãr 6 Adrian Marchiº 6 ªtefan Marinca (Lim er ick, Irlanda) 6 Viorel Micula (Sac ra mento, SUA) 6 Mihai Nae (Viena) 6 Ion Negrei (Chiºinãu) 6 Nina Negru (Chiº inãu) 6 Ada Olos (Montreal, Can- ada) 6 Mihai Pãtraºcu 6 Gheorghe Pârja 6 Viorica Pâtea (Salamanca, Spania) 6 Gheorghe Pop 6 Mihai Prepeliþã (Moscova, Rusia) 6 Paul Remetean (Tou louse, Franþa) 6 George Roca (Syd ney, Aus tra lia) 6 Origen Sabãu (Apateu, Ungaria) 6 Lucia Soreanu ªiugariu (Aachen, Germ ania) 6 Vasile Tãrâþeanu (Cernãuþi) 6 Teresia B. -

Ierusalim PAG

Consiliul de Conducere şi Adunarea Generală a F.C.E.R.-C.M. PAG. 3, 6, 7, 13 „Podurile Toleranței“, PUBLICAŢIE A FEDERAŢIEI COMUNITĂŢILOR EVREIEŞTI DIN ROMÂNIA a cincea ediție ANUL LXII = NR. 516-517 (1316-1317) = 1 – 31 MAI 2018 = 16 IYAR – 17 SIVAN 5778 = 28 PAGINI – 3 LEI Ierusalim PAG. 4, 5, 16 ISRAEL, 70 de ani de independență PAG. 8 Șavuot 5778 la Templul Coral din Bucureşti PAG. 10 Ambasada SUA PAG. 9, 11, 25 Comunități Primele Delegație BB Franța la București: „Pentru noi, România trei ambasade înseamnă PAG. 13 inaugurate şi țara de origine a lui Elie Wiesel” PAG. 12 Față în față cu Marcel Grinberg O inimă bună – Gaonul Efraim Gutman, la 90 de ani PAG. 12 Lansarea albumului Ambasada Paraguay Ambasada Guatemala „Temple şi Sinagogi PAG. 17 Isac Herzog, parlamentari, numeroase arătat că angajamentul Israelului față de din România. Ambasada SUA alte personalități. Ierusalim nu este numai un angajament După ridicarea drapelului și intona- față de istoria poporului evreu, ci și față Patrimoniu Evreiesc, La 14 mai a.c., în ziua în care în rea imnului american, a luat cuvântul de toți locuitorii Ierusalimului. „Ierusalimul Național şi Universal” urmă cu 70 de ani David ben Gurion David Friedman. El a arătat că mutarea este un microcosmos al capacității noas- declara independența Statului Israel și Ambasadei americane este rezultatul tre, evrei și arabi, de a coexista în același președintele SUA a recunoscut Israelul, „viziunii, curajului și clarității morale ale loc. Unitatea Ierusalimului este văzută Expoziția PAG. 17 la Ierusalim a fost inaugurată Ambasada președintelui Donald Trump. -

On the Advantages of Minority Condition in the Romanian

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS SAPIENTIAE, PHILOLOGICA, 9, 1 (2017) 7–16 DOI: 10 .1515/ausp-2017-0001 On the Advantages of Minority Condition in the Romanian-Hungarian Cultural and Literary Relations Valentin TRIFESCU University of Art and Design (Cluj-Napoca, Romania) Department of Theoretical Disciplines valentintrifescu@yahoo .fr Abstract. This study analyses the way in which cultural and literary Romanian-Hungarian relations have evolved since World War I in the context of the rapport between majority and minority . Our aim is to analyze, from an interdisciplinary and diachronic perspective, the implications related to culture and identity of the process studied . We raise the problem of bilingualism and its manifestation at the level of bilateral cultural relations, in general, and literary criticism, in particular . Keywords: collective identities, literary criticism, Transylvania, minority- majority, regionalism . Paradoxically, the ones that lost may be considered winners (or the winning side) and the ones that won, losers . This is the formula that summarizes the rapport between the advantages and disadvantages of the historical events of the twentieth century, especially the two World Wars, on the cultural and literary Romanian-Hungarian relations, in general, and the Transylvanian case, in particular . Certainly, our approach is diachronic . We took no interest in the exceptions, gaps or breaks, but in the developments of the cultural phenomenon, its metamorphoses and possibilities to endure through time . With much visionary spirit, in a Transylvanian-Hungarian society going through collective identitarian depression of identity caused by the passage of Transylvania under the administration of Romanian authorities in Bucharest (Olcar 2011, 10), the reformed priest and publicist Dezső László (1904–1973) optimistically described the cultural advantages of minority life . -

Agenda Diplomaţiei Publice România – Israel Decembrie 2010

Agenda diplomaţiei publice România – Israel Decembrie 2010 Tudor Giurgiu – master classes la Sam Spiegel Film & Television School, Jerusalem La invitaţia Sam Spiegel Film & Television School din Ierusalim, regizorul şi producătorul român Tudor Giurgiu va oferi studenţilor israelieni o serie de master classes despre istoria cinematografiei româneşti, dar şi despre noul val cinematografic român. Prelegerile vor acoperi subiecte precum finanţare, distribuţie în România şi pe plan internaţional, regizori de film de primă importanţă, festivaluri româneşti de film. De asemenea, va fi prezentat un studiu comparativ între industria cinematografică românească şi cea israeliană, întrucât există multe similarităţi în ceea ce priveşte producţia filmelor cu buget mic şi aprecierea internaţională a acestora. Va fi abordată şi problema dificilă a supravieţuirii/reuşitei, cu bugete (atât de) mici, în lumea în continuă schimbare/dezvoltare a filmului occidental. Pentru participarea la aceste master classes sunt selectaţi aproximativ 20 de studenţi de la Departamentul Managementul Producţiei, anii de studiu II, III şi IV. Înfiinţată în 1989 de către Ministerul israelian al Educaţiei şi Culturii şi de Jerusalem Foundation, Şcoala de Film şi Televiziune Sam Spiegel din Ierusalim este, la ora actuală, unica instituţie israeliană dedicată care oferă studii de specialitate în domeniul filmului şi televiziunii. Instituţii şi studiouri personale, la fel de prestigioase, precum Beit Zvi (Ramat Gan, lângă Tel Aviv) sau Nissan Nativ Acting Studio (Tel Aviv şi Ierusalim) oferă cursuri specializate centrate pe actorie sau regie de teatru. Absolvenţi ai acestor programe de studii au devenit deja cunoscuţi şi premiaţi actori şi regizori israelieni. Pe tot parcursul anului academic, Şcoala de Film şi Televiziune Sam Spiegel organizează o serie de master classes oferite de specialişti şi personalităţi internaţionale din lumea cinematografiei, reunite sub titulatura „Great Masters Program”: printre invitaţi s-au numărat David Lynch, Wim Wenders sau Todd Solondz. -

O Sută De Ani De Cartografie Lingvistică Românească

La « semence incendiaire » d’une parole nouvelle : Plămânul sălbatec de Paul Păun Giovanni MAGLIOCCO Key-words: avant-gardes, « Alge », The surrealist Group of Bucharest, imaginary, rhetoric, action, story, dream, alchemy «Blanche ville noyée dans l’adolescence...» : de la période algiste (1930– 1933) à Plămânul sălbatec (1939) Dans le panorama frénétique et excentrique des Avant-gardes roumaines, l’œuvre poétique et picturale de Paul Păun a eu un destin obscur et singulier. Solitaire et apparemment marginale, elle semble se vouer au silence impénétrable d’une vie cachée et énigmatique. Si, comme l’affirme Monique Yaari dans une de ses études consacrées au poéte, l’œuvre publiée avant 1975 est peu connue en dehors de la Roumanie, le seul volume publié en français en Israël, La Rose Parallèle (Haifa, 1975), a eu lui aussi une circulation limitée, parce qu’il a paru « only privately […] without copyright, in the best Situationist anarchist tradition, and is now out print »; ce qui, selon Yaari, rend cette œuvre une véritable « chimère » (Yaari 1994 : 108). Paul Păun, pseudonyme de Zaharia Herşcovici1, a débuté très jeune en 1931 sur la revue « Alge », dirigée par Aurel Baranga, et a collaboré aussi à d’autres revues d’avant-garde; en particulier à « unu », dirigée par Saşa Pană, où en 1932 il a publié l’un des poèmes les plus représentatifs de sa première production poétique : Epitaf pentru omul-bou (Păun 1932 : 2–3). Cette première phase de sa carrière artistique, que Monique Yaari pour sa précocité n’hésite pas à definir « rimbaldienne » (Yaari 1994 : 108), se situe parfaitement dans l’atmosphère exubérante, irrévérencieuse et cocasse de « Alge ». -

Corespondenta Ierusalim: Gina Pana Si Avangarda

Scris de tesu.solomovici pe 18 decembrie 2010, 17:32 Corespondenta Ierusalim: Gina Pana si avangarda romaneasca intre Bucuresti, Paris si Tel Aviv Om de cultura autentic, doamna Gina Pana, directoarea Institului Cultural Roman din Tel Aviv, a sesizat imensul potential al temei si a organizat Conferinta Internationala despre avangarda romaneasca, desfasurata la Universitatea din Ierusalim (12-14 decembrie 2010). A fost subliniat cu acest prilej faptul ca in ultimul deceniu a luat o amploare deosebita interesul pentru avangarda romaneasca si interferentele ei cu avangarda europeana in genere, atat in planul literaturii de avangarda, cat si in domeniul picturii, sculpturii si arhitecturii. Studiile aparute in Romania, Franta, Israel si in alte tari pun in valoare rolul avangardei in reinnoirea mijloacelor artistice, locul si semnificatia acesteia in cadrul miscarilor artistice moderniste. Conferinta, organizata de Institutul Cultural Roman de la Tel Aviv si Centrul de studiere a istoriei evreilor din Romania de la Universitatea Ebraica din Ierusalim, si-a propus o abordare a avangardei din perspectiva a doua aspecte semnificative: 1. prezenta unor avangardisti romani (sau originari din Romania) atat in avangarda din Romania, cat si in cea franceza (Tristan Tzara, Ilarie Voronca, Gherasim Luca, Benjamin Fondane, Claude Sernet, Victor Brauner, Marcel Iancu, Herold, Jules Perahims.a.) 2. semnificatia prezentei a numerosi artisti evrei in miscarea de avangarda din Romania, inclusiv optiunea unora dintre ei de a se stabili, in ultima parte a vietii lor, in Israel, ca si efortul lor de a impune innoirile lor avangardiste in peisajul cultural-artistic israelian (Marcel Iancu, Sesto Pals, Paul Paun, Jean David s.a.) Au fost invitati sa conferentieze Ion Pop, Paul Cernat, Augustin Ioan, Ovidiu Morar, Camelia Craciun (Romania), Michael Finkenthal, Cosana Nicolae-Eram (Statele Unite), (Moshe Idel, Marlene Braester, Leon Volovici, Milly Heyd, Cyril Aslanov, Simona Or-Munteanu, Vlad Solomon (Israel), Petre Raileanu (Franta), Tom Sandqvist (Suedia)), Radu Stern(Elvetia). -

Strumenti Per La Didattica E La Ricerca

strumenti per la didattica e la ricerca – 152 – BiBlioteca di studi di Filologia moderna aree anglofona, Francofona, di germanistica, sezione di comparatistica, Filologie e studi linguistici, e sezioni di di iberistica, rumenistica, scandinavistica, slavistica, turcologia, ugrofinnistica e studi italo-ungheresi, riviste Direttore Beatrice töttössy Coordinamento editoriale martha luana canfield,p iero ceccucci, massimo ciaravolo, John denton, mario domenichelli, Fiorenzo Fantaccini, ingrid Hennemann, michela landi, donatella pallotti, stefania pavan, ayşe saraçgil, rita svandrlik, angela tarantino, Beatrice töttössy Segreteria editoriale arianna antonielli, laboratorio editoriale open access, via santa reparata 93, 50129 Firenze tel +39 0552756664; fax +39 0697253581; email: [email protected]; web: <http://www.collana-filmod.unifi.it> Comitato internazionale nicholas Brownlees, università degli studi di Firenze massimo Fanfani, università degli studi di Firenze arnaldo Bruni, università degli studi di Firenze murathan mungan, scrittore martha luana canfield,u niversità degli studi di Firenze Álvaro mutis, scrittore richard allen cave, royal Holloway college, university of london Hugh nissenson, scrittore piero ceccucci, università degli studi di Firenze donatella pallotti,u niversità degli studi di Firenze massimo ciaravolo, università degli studi di Firenze stefania pavan, università degli studi di Firenze John denton, università degli studi di Firenze peter por, cnr de paris mario domenichelli, università degli studi di Firenze -

Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives (XVIII-XX Centuries)

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives (XVIII-XX centuries) Brie, Mircea and Şipoş, Sorin and Horga, Ioan University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44026/ MPRA Paper No. 44026, posted 30 Jan 2013 09:17 UTC ETHNO-CONFESSIONAL REALITIES IN THE ROMANIAN AREA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (XVIII-XX CENTURIES) ETHNO-CONFESSIONAL REALITIES IN THE ROMANIAN AREA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (XVIII-XX CENTURIES) Mircea BRIE Sorin ŞIPOŞ Ioan HORGA (Coordinators) Foreword by Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border (workshop: Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives), held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011. This international conference, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council, was an event run within the project of Action Jean Monnet Programme of the European Commission n. 176197-LLP-1- 2010-1-RO-AJM-MO CONTENTS Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Foreword ................................................................................................................ 7 CONFESSION AND CONFESSIONAL MINORITIES Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Confessionalisation and Community Sociability (Transylvania, 18th Century – First Half of the