Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle Mitsuko Uchida Ludwig Van

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

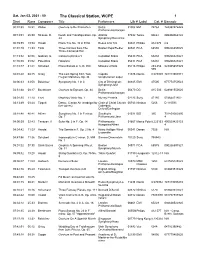

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists Asmir Tobudic Gerhard Widmer Austrian Research Institute for Department of Computational Perception, Artificial Intelligence, Vienna Johannes Kepler University, Linz [email protected] Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Vienna [email protected] Abstract CD recordings and the printed score of the music. Exper- iments show that the system indeed captures some aspect of An application of relational instance-based learn- the pianists' playing style: the machine's performances of un- ing to the complex task of expressive music per- seen pieces are substantially closer to the real performances formance is presented. We investigate to what ex- of the `training' pianist than those of all other pianists in our tent a machine can automatically build `expres- data set. An interesting by-product of the pianists' `expres- sive profiles’ of famous pianists using only min- sive models' is demonstrated: the automatic identification of imal performance information extracted from au- pianists based on their style of playing. And finally, the ques- dio CD recordings by pianists and the printed tion of automatic style replication is briefly discussed. score of the played music. It turns out that the The rest of the paper is laid out as follows. After a short machine-generated expressive performances on un- introduction to the notion of expressive music performance seen pieces are substantially closer to the real per- (Section 2), Section 3 describes the data and its representa- formances of the `trainer' pianist than those of all tion in FOL. We also discuss how the complex task of learn- others. -

Conducting from the Piano: a Tradition Worth Reviving? a Study in Performance

CONDUCTING FROM THE PIANO: A TRADITION WORTH REVIVING? A STUDY IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: MOZART’S PIANO CONCERTO IN C MINOR, K. 491 Eldred Colonel Marshall IV, B.A., M.M., M.M, M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor David Itkin, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Marshall IV, Eldred Colonel. Conducting from the Piano: A Tradition Worth Reviving? A Study in Performance Practice: Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C minor, K. 491. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 74 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. Is conducting from the piano "real conducting?" Does one need formal orchestral conducting training in order to conduct classical-era piano concertos from the piano? Do Mozart piano concertos need a conductor? These are all questions this paper attempts to answer. Copyright 2018 by Eldred Colonel Marshall IV ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONDUCTING FROM THE KEYBOARD ............ 1 CHAPTER 2. WHAT IS “REAL CONDUCTING?” ................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 3. ARE CONDUCTORS NECESSARY IN MOZART PIANO CONCERTOS? ........................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 “Jeunehomme” (1777) ............................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 13 in C major, K. 415 (1782) ............................................................. 23 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 (1785) ............................................................. 25 Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. -

Brentano String Quartet

“Passionate, uninhibited, and spellbinding” —London Independent Brentano String Quartet Saturday, October 17, 2015 Riverside Recital Hall Hancher University of Iowa A collaboration with the University of Iowa String Quartet Residency Program with further support from the Ida Cordelia Beam Distinguished Visiting Professor Program. THE PROGRAM BRENTANO STRING QUARTET Mark Steinberg violin Serena Canin violin Misha Amory viola Nina Lee cello Selections from The Art of the Fugue Johann Sebastian Bach Quartet No. 3, Op. 94 Benjamin Britten Duets: With moderate movement Ostinato: Very fast Solo: Very calm Burlesque: Fast - con fuoco Recitative and Passacaglia (La Serenissima): Slow Intermission Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 67 Johannes Brahms Vivace Andante Agitato (Allegretto non troppo) Poco Allegretto con variazioni The Brentano String Quartet appears by arrangement with David Rowe Artists www.davidroweartists.com. The Brentano String Quartet record for AEON (distributed by Allegro Media Group). www.brentanoquartet.com 2 THE ARTISTS Since its inception in 1992, the Brentano String Quartet has appeared throughout the world to popular and critical acclaim. “Passionate, uninhibited and spellbinding,” raves the London Independent; the New York Times extols its “luxuriously warm sound [and] yearning lyricism.” In 2014, the Brentano Quartet succeeded the Tokyo Quartet as Artists in Residence at Yale University, departing from their fourteen-year residency at Princeton University. The quartet also currently serves as the collaborative ensemble for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The quartet has performed in the world’s most prestigious venues, including Carnegie Hall and Alice Tully Hall in New York; the Library of Congress in Washington; the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam; the Konzerthaus in Vienna; Suntory Hall in Tokyo; and the Sydney Opera House. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle, Direction

SAMEDI 27 FÉVRIER – 20H Richard Wagner Ouverture des Maîtres chanteurs de Nuremberg Arnold Schönberg Symphonie de chambre n° 1 – version pour grand orchestre entracte Johannes Brahms Symphonie n° 2 Berliner Philharmoniker Sir Simon Rattle, direction Toute photographie et tout enregistrement sont strictement interdits. La Deutsche Bank se réjouit d’être le partenaire des Berliner Philharmoniker. | Samedi 27 février 27 | Samedi Ce concert est enregistré par France Musique. Fin du concert vers 21h35. Berliner Philharmoniker Berliner 27-02 BERLINER RATTLE.indd 1 24/02/10 15:57 Richard Wagner Ouverture des Maîtres chanteurs de Nuremberg Composition : 1861-1867, mais projeté dès 1845. Création : le 21 juin 1868, au Hoftheater de Munich, sous la direction de Hans von Bülow. Effectif : piccolo, 2 flûtes, 2 hautbois, 2 clarinettes, 2 bassons – 4 cors, 5 trompettes, 2 trombones, tuba basse – timbales, triangle, tambour, cymbales – harpe, luth – cordes. Durée : environ 9 minutes. La découverte, en 1845, du personnage historique de Hans Sachs, « dernière incarnation de l’esprit populaire artistiquement créateur en art » (Une communication à mes amis, 1851), pousse Wagner à esquisser les grandes lignes des Maîtres chanteurs de Nuremberg ; s’il faut attendre les années 1860 (et la composition de Lohengrin, de Tristan et d’une grande partie de L’Anneau du Nibelung) pour que le compositeur s’y attelle véritablement, la thématique principale, elle, est déjà présente : réflexion sur l’art, l’opéra prône la réconciliation entre tradition (représentée par la confrérie des maîtres chanteurs) et nouveauté (incarnée par le jeune Walther). Comme une illustration de cette problématique, la musique se réapproprie des tournures « anciennes » (forme bar, fugue, contrepoint) et délaisse le chromatisme tristanien pour un vigoureux diatonisme : Wagner « forge […] pour chaque œuvre une langue nouvelle », comme le fait remarquer Nietzsche dans sa Considération inactuelle n° 4. -

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mu

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music 1988 December The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris The Russian piano concerto could not have had more inauspicious beginnings. Unlike the symphonic poem (and, indirectly, the symphony) - genres for which Glinka, the so-called 'Father of Russian Music', provided an invaluable model: 'Well? It's all in "Kamarinskaya", just as the whole oak is in the acorn' to quote Tchaikovsky - the Russian piano concerto had no such indigenous prototype. All that existed to inspire would-be concerto composers were a handful of inferior pot- pourris and variations for piano and orchestra and a negligible concerto by Villoing dating from the 1830s. Rubinstein's five con- certos certainly offered something more substantial, as Tchaikovsky acknowledged in his First Concerto, but by this time the century was approaching its final quarter. This absence of a prototype is reflected in all aspects of Russian concerto composition. Most Russian concertos lean perceptibly on the stylistic features of Western European composers and several can be justly accused of plagiarism. Furthermore, Russian composers faced formidable problems concerning the structural organization of their concertos, a factor which contributed to the inability of several, including Balakirev and Taneyev, to complete their works. Even Tchaikovsky encountered difficulties which he was not always able to overcome. The most successful Russian piano concertos of the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky's No.1 in B flat minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Concerto in C sharp minor and Balakirev's Concerto in E flat, returned ii to indigenous sources of inspiration: Russian folk song and Russian orthodox chant. -

Programme Information

Programme information Saturday 6th April to Friday 12th April 2019 WEEK 15 Above: Alan Titchmarsh and Rob Cowan ANDRE PREVIN: A LIFE IN MUSIC (continueD) Saturday 6th April 7am to 10am: Alan TitcHmarsH 7pm to 9pm: Cowan’s Classics with Rob Cowan On what would have been André Previn’s 90th birthday, Alan Titchmarsh and Rob Cowan complete Classic FM’s week-long tribute to the great conductor, pianist and composer. From Rob Cowan: “Celebrating what would have been André Previn’s 90th on Cowan’s Classics brings back precious memories of a breakfast interview in Vienna back in 1997, talking to the great man about Ravel, Richard Strauss, Vaughan Williams, Mozart and film music. I remember his suave manner, caustic wit and obvious enthusiasm for the music he loved most. I’ve a terrific selection planned, ranging from Vaughan Williams evoking Westminster at night, to something sleek and sweet by Previn himself, Satie’s restful Gymnopedie No. 1 and Rachmaninov’s most famous piano concerto with Vladimir Ashkenazy as soloist. Here’s hoping that on Classic FM, I play all the right pieces in the right order...” Classic FM is available across the UK on 100-102 FM, DAB Digital radio anD TV, the Classic FM app, at ClassicFM.com and on the Global Player. 1 WEEK 15 SATURDAY 6TH APRIL 7am to 10am: ALAN TITCHMARSH Join Alan for his Great British Discovery and Gardening Tip after 8am, followed by a very special Classic FM Hall of Fame Hour at 9am. André Previn died in February at the age of 89; today would have been his 90th birthday, so, ahead of a special programme with Rob Cowan tonight, Alan dedicates the Classic FM Hall of Fame Hour to Previn’s finest recordings as both conductor and pianist.