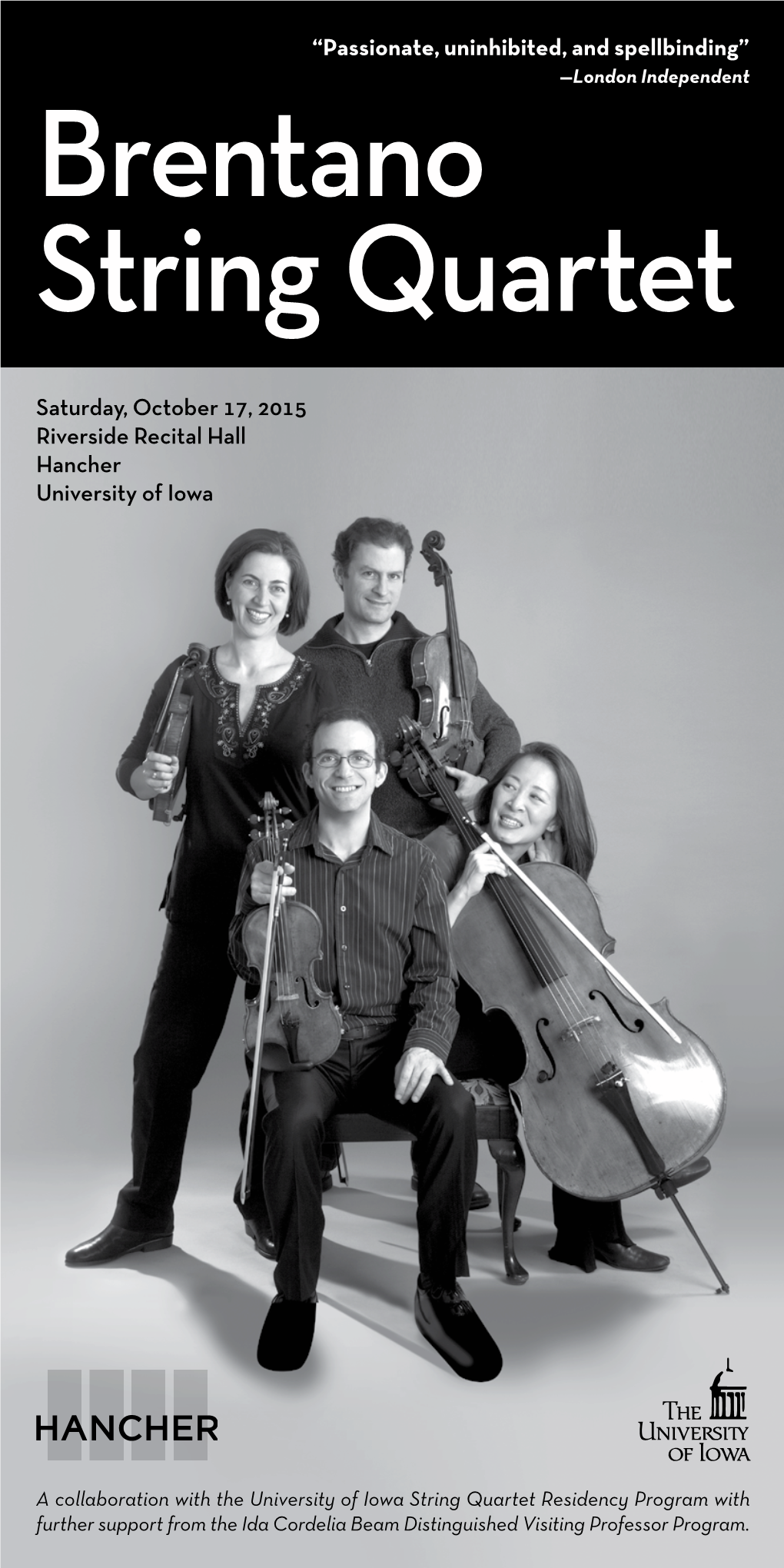

Brentano String Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

Nasher Sculpture Center's Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Macke

Nasher Sculpture Center’s Soundings Concert Honoring President John F. Kennedy with New Work by American Composer Steven Mackey to be Performed at City Performance Hall; Guaranteed Seating with Soundings Season Ticket Package Brentano String Quartet Performance of One Red Rose, co-commissioned by the Nasher with Carnegie Hall and Yellow Barn, moved to accommodate bigger audience. DALLAS, Texas (September 12, 2013) – The Nasher Sculpture Center is pleased to announce that the JFK commemorative Soundings concert will be performed at City Performance Hall. Season tickets to Soundings are now on sale with guaranteed seating to the special concert honoring President Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his death with an important new work by internationally renowned composer Steven Mackey. One Red Rose is written for the Brentano String Quartet in commemoration of this anniversary, and is commissioned by the Nasher (Dallas, TX) with Carnegie Hall (New York, NY) and Yellow Barn (Putney, VT). The concert will be held on Saturday, November 23, 2013 at 7:30 pm at City Performance Hall with celebrated musicians; the Brentano String Quartet, clarinetist Charles Neidich and pianist Seth Knopp. Mr. Mackey’s One Red Rose will be performed along with seminal works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage. An encore performance of One Red Rose, will take place Sunday, November 24, 2013 at 2 pm at the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. Both concerts will include a discussion with the audience. Season tickets are now available at NasherSculptureCenter.org and individual tickets for the November 23 concert will be available for purchase on October 8, 2013. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

Msm Camerata Nova

Saturday, March 6, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM CAMERATA NOVA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM JAMES LEE III A Narrow Pathway Traveled from Night Visions of Kippur (b. 1975) CHARLES WUORINEN New York Notes (1938–2020) (Fast) (Slow) HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Chôros No. 7 (1887–1959) MAURICE RAVEL Introduction et Allegro (1875–1937) CAMERATA NOVA VIOLIN 1 VIOLA OBOE SAXOPHONE HARP Youjin Choi Sara Dudley Aaron Zhongyang Ling Minyoung Kwon New York, New York New York, New York Haettenschwiller Beijing, China Seoul, South Korea Baltimore, Maryland VIOLIN 2 CELLO PERCUSSION PIANO Ally Cho Rei Otake CLARINET Arthur Seth Schultheis Melbourne, Australia Tokyo, Japan Ki-Deok Park Dhuique-Mayer Baltimore, Maryland Chicago, Illinois Champigny-Sur-Marne, France FLUTE Tarun Bellur Marcos Ruiz BASSOON Plano, Texas Miami, Florida Matthew Pauls Simi Valley, California ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists

Learning to Play Like the Great Pianists Asmir Tobudic Gerhard Widmer Austrian Research Institute for Department of Computational Perception, Artificial Intelligence, Vienna Johannes Kepler University, Linz [email protected] Austrian Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Vienna [email protected] Abstract CD recordings and the printed score of the music. Exper- iments show that the system indeed captures some aspect of An application of relational instance-based learn- the pianists' playing style: the machine's performances of un- ing to the complex task of expressive music per- seen pieces are substantially closer to the real performances formance is presented. We investigate to what ex- of the `training' pianist than those of all other pianists in our tent a machine can automatically build `expres- data set. An interesting by-product of the pianists' `expres- sive profiles’ of famous pianists using only min- sive models' is demonstrated: the automatic identification of imal performance information extracted from au- pianists based on their style of playing. And finally, the ques- dio CD recordings by pianists and the printed tion of automatic style replication is briefly discussed. score of the played music. It turns out that the The rest of the paper is laid out as follows. After a short machine-generated expressive performances on un- introduction to the notion of expressive music performance seen pieces are substantially closer to the real per- (Section 2), Section 3 describes the data and its representa- formances of the `trainer' pianist than those of all tion in FOL. We also discuss how the complex task of learn- others. -

Concert Programdownload Pdf(349

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Stockhausen's Mantra For Two Pianos Eric Huebner and Steven Beck, pianos Sound and electronic interface design: Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Sound projection: Chris Jacobs and Ryan MacEvoy McCullough Saturday, October 14, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Mantra (1970) Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928 – 2007) Program Note by Katherine Chi To say it as simply as possible, Mantra, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed. When I was composing the work, I had no accessory feelings or thoughts; I knew only that I had to fulfill the mantra. And it demanded itself, it just started blossoming. As it was being constructed through me, I somehow felt that it must be a very true picture of the way the cosmos is constructed, I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right. And this was due to the integral systemization - the combination of the scalar idea with the idea of deriving everything from the One. It shines very strongly. - Karlheinz Stockhausen Mantra is a seminal piece of the twentieth century, a pivotal work both in the context of Stockhausen’s compositional development and a tour de force contribution to the canon of music for two pianos. It was written in 1970 in two stages: the formal skeleton was conceived in Osaka, Japan (May 1 – June 20, 1970) and the remaining work was completed in Kürten, Germany (July 10 – August 18, 1970). -

Solzh 19-20 Short

IGNAT SOLZHENITSYN 2019-20 SHORT BIO {206 WORDS} IGNAT SOLZHENITSYN Recognized as one of today's most gifted artists, and enjoying an active career as both conductor and pianist, Ignat Solzhenitsyn's lyrical and poignant interpretations have won him critical acclaim throughout the world. Principal Guest Conductor of the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and Conductor Laureate of the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, Ignat Solzhenitsyn has recently led the symphonies of Baltimore, Cincinnati, Dallas, Indianapolis, Milwaukee, Seattle, and Toronto, the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, the Czech National Symphony, as well as the Mariinsky Orchestra and the St. Petersburg Philharmonic. He has partnered with such world-renowned soloists as Richard Goode, Gary Graffman, Gidon Kremer, Anne-Sophie Mutter, Garrick Ohlsson, Mstislav Rostropovich, and Mitsuko Uchida. His extensive touring schedule in the United States and Europe has included concerto performances with numerous major orchestras, including those of Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Seattle, Baltimore, Montreal, Toronto, London, Paris, Israel, and Sydney, and collaborations with such distinguished conductors as Herbert Blomstedt, James Conlon, Charles Dutoit, Valery Gergiev, André Previn, Gerard Schwarz, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Yuri Temirkanov and David Zinman. A winner of the Avery Fisher Career Grant, Ignat Solzhenitsyn serves on the faculty of the Curtis Institute of Music. He has been featured on many radio and television specials, including CBS Sunday Morning and ABC’s Nightline. CURRENT AS OF: 18 NOVEMBER 2019 PLEASE DESTROY ANY PREVIOUS BIOGRAPHICAL MATERIALS. PLEASE MAKE NO CHANGES, EDITS, OR CUTS OF ANY KIND WITHOUT SPECIFIC PERMISSION.. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, August 4th, 2012, 5:00-6:00 p.m. Claude Debussy (1862-1918). Danse (Tarantelle styrienne) (1891, 1903). David Allen Wehr, piano. Connoiseur Soc 4219, Tr 4, 5:21 Debussy. Danse, orch. Ravel (1923). Philharmonia Orchestra, Geoffrey Simon. Cala 1024, Tr 9, 5:01 Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Shéhérazade (1903). Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano, Cleveland Orchestra, Pierre Boulez. DG 2121, Tr 1-3, 17:16 Ravel. Introduction and Allegro (1905). Rachel Masters, harp, Christopher King, clarinet, Ulster Orchestra, Yan Pascal Tortelier. Chandos 8972, Tr 7, 11:12 Debussy. Sarabande, from Pour le piano (1901). Larissa Dedova, piano. Centaur 3094, Disk 4, Tr 6, 4:21 Debussy. Sarabande, orch. Ravel (1923). Ulster Orchestra, Yan Pascal Tortelier. Chandos 9129, Tr 2, 4:29 This time, he’d show them. The Paris Conservatoire accepted Ravel as a piano student at age 16, and even though he won a piano competition, more than anything he wanted to compose. But the Conservatory was a hard place. He never won the fugue prize, never won the composition prize, never won anything for writing music and they sent him packing. Twice. He studied with the great Gabriel Fauré, in school and out, but he just couldn’t make any headway with the ruling musical authorities. If it wasn’t clunky parallelisms in his counterpoint, it was unresolved chords in his harmony, but whatever the reason, four times he tried for the ultimate prize in composition, the Prix de Rome, and four times he was refused. -

Wuorinen Printable Program

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Celebrating Charles Wuorinen at 80 featuring Ensemble SIGNAL Brad Lubman, conductor Tuesday, April 24, 2018 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Charles Wuorinen (b. 1938) iRidule Jacqueline Leclair, oboe soloist Spin 5 Olivia De Prato, violin soloist Intermission Megalith Eric Huebner, piano soloist PERSONNEL Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, Music Director Paul Coleman, Sound Director Olivia De Prato, Violin Lauren Radnofsky, Cello Ken Thomson, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet Adrián Sandí, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet David Friend, Piano 1 Oliver Hagen, Piano 2 Karl Larson, Piano 3 Georgia Mills, Piano 4 Matt Evans, Vibraphone, Piano Carson Moody, Marimba 1 Bill Solomon, Marimba 2 Amy Garapic, Marimba 3 Brad Lubman, Marimba Sarah Brailey, Voice 1 Mellissa Hughes, Voice 2 Kirsten Sollek, Voice 4 Charles Wuorinen In 1970 Wuorinen became the youngest composer at that time to win the Pulitzer Prize (for the electronic work Time's Encomium). The Pulitzer and the MacArthur Fellowship are just two among many awards, fellowships and other honors to have come his way. Wuorinen has written more than 260 compositions to date. His most recent works include Sudden Changes for Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Exsultet (Praeconium Paschale) for Francisco Núñez and the Young People's Chorus of New York, a String Trio for the Goeyvaerts String Trio, and a duo for viola and percussion, Xenolith, for Lois Martin and Michael Truesdell. The premiere of of his opera on Annie Proulx's Brokeback Mountain was was a major cultural event worldwide.