Conducting from the Piano: a Tradition Worth Reviving? a Study in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 88

BOSTON SYMPHONY v^Xvv^JTa Jlj l3 X JlVjl FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON THURSDAY A SERIES EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 Exquisite Sound From the palaces of ancient Egypt to the concert halls of our modern cities, the wondrous music of the harp has compelled attention from all peoples and all countries. Through this passage of time many changes have been made in the original design. The early instruments shown in drawings on the tomb of Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.) were richly decorated but lacked the fore-pillar. Later the "Kinner" developed by the Hebrews took the form as we know it today. The pedal harp was invented about 1720 by a Bavarian named Hochbrucker and through this ingenious device it be- came possible to play in eight major and five minor scales complete. Today the harp is an important and familiar instrument providing the "Exquisite Sound" and special effects so important to modern orchestration and arrange- ment. The certainty of change makes necessary a continuous review of your insurance protection. We welcome the opportunity of providing this service for your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 PAIGE OBRION RUSSELL Insurance Since 1876 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor EIGHTY-EIGHTH SEASON 1968-1969 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ROBERT H.GARDINER Vice-President EDWARD M. -

George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759)

Hey Kids, Meet George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759) George Frideric Handel was born on February 23, 1685 in the North German province of Saxony, in the same year as Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. George's father wanted him to be a lawyer, though music had captivated his attention. His mother, in contrast, supported his interest in music, and he was allowed to take keyboard and music composition lessons. His aunt gave him a harpsichord for his seventh birthday which Handel played whenever he had the chance. In 1702 Handel followed his father's wishes and began his study of law at the University of Halle. After his father's death in the following year, he returned to music and accepted a position as the organist at the Protestant Cathedral. In the next year he moved to Hamburg and accepted a position as a violinist and harpsichordist at the opera house. It was there that Handel's first operas were written and produced. In 1710, Handel accepted the position of Kapellmeister to George, Elector of Hanover, who was soon to be King George I of Great Britain. In 1712 he settled in England where Queen Anne gave him a yearly income. In the summer of 1717, Handel premiered one of his greatest works, Water Music, in a concert on the River Thames. The concert was performed by 50 musicians playing from a barge positioned closely to the royal barge from which the King listened. It was said that King George I enjoyed it so much that he requested the musicians to play the suite three times during the trip! By 1740, Handel completed his most memorable work - the Messiah. -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759)

Hey Kids, Meet George Frideric Handel German Baroque Era Composer (1685-1759) George Frideric Handel was born on February 23, 1685 in the North German province of Saxony, in the same year as Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach. George's father wanted him to be a lawyer, though music had captivated his attention. His mother, in contrast, supported his interest in music, and he was allowed to take keyboard and music composition lessons. His aunt gave him a harpsichord for his seventh birthday which Handel played whenever he had the chance. In 1702 Handel followed his father's wishes and began his study of law at the University of Halle. After his father's death in the following year, he returned to music and accepted a position as the organist at the Protestant Cathedral. In the next year he moved to Hamburg and accepted a position as a violinist and harpsichordist at the opera house. It was there that Handel's first operas were written and produced. In 1710, Handel accepted the position of Kapellmeister to George, Elector of Hanover, who was soon to be King George I of Great Britain. In 1712 he settled in England where Queen Anne gave him a yearly income. In the summer of 1717, Handel premiered one of his greatest works, Water Music, in a concert on the River Thames. The concert was performed by 50 musicians playing from a barge positioned closely to the royal barge from which the King listened. It was said that King George I enjoyed it so much that he requested the musicians to play the suite three times during the trip! By 1740, Handel completed his most memorable work - the Messiah. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

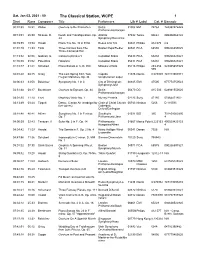

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

Acclaimed Pianist and Conductor Jeffrey Kahane Named a Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music

Web Version | Contact Media Reps | Find Experts Like Tweet Forward Acclaimed Pianist and Conductor Jeffrey Kahane Named a Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music CONTACT: Evan Calbi 213/740-3229 [email protected] Libby Huebner 562/799-6055 and Laura Stegman 310/470-6321 [email protected] Jeffrey Kahane, the acclaimed pianist and music director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (LACO), will join the USC Thornton School of Music faculty part time in fall 2015 during his final two years with LACO, becoming a full-time professor after he steps down from his LACO post in 2017. He will be transitioning to music director laureate at LACO after a 20-year run, the longest of any music director in the ensemble’s history. This appointment ensures he will remain a musical force in Los Angeles for years to come. Officials from USC Thornton and LACO made the joint announcement today that Kahane will join the keyboard studies department to teach piano as well as other classes. “Jeffrey is an important addition to the USC Thornton faculty as we continue to assemble what we believe to be the strongest music faculty in the world,” said Robert Cutietta, dean of USC Thornton. “He has such a strong humanities background that he will be a diverse and strong addition to our school. The sky is the limit on what might evolve.” Kahane said he was “deeply honored to join the immensely distinguished faculty” of USC Thornton and said he is “profoundly grateful for their warm and enthusiastic welcome and support.” Kahane said that a commitment to education has been a central part of his musical life for more than two decades. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Pastiche for Piano on Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music

Pastiche For Piano On Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music Download pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2619 times and last read at 2021-09-28 10:12:03. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Method, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 sheet music has been read 3180 times. Opus calidoscopium in memory of sorabji op 2 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 19:02:59. [ Read More ] Pastiche 2017 Pastiche 2017 sheet music has been read 2663 times. Pastiche 2017 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 02:51:33. [ Read More ] Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 sheet music has been read 2729 times. Virtuoso etude no 4 in memory of sorabji nocturne op 1 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 05:00:02.