PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Cultural Bridges: Benjamin Britten and Russia

BUILDING CULTURAL BRIDGES: BENJAMIN BRITTEN AND RUSSIA Book Review of Benjamin Britten and Russia, by Cameron Pyke Maja Brlečić Benjamin Britten visited Soviet Russia during a time of great trial for Soviet artists and intellectuals. Between the years of 1963 and 1971, he made six trips, four formal and two private. During this time, the communist regime within the Soviet Union was at its heyday, and bureaucratization of culture served as a propaganda tool to gain totalitarian control over all spheres of public activity. This was also a period during which the international political situation was turbulent; the Cold War was at its height with ongoing issues of nuclear armaments, the tensions among the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom ebbed and flowed, and the atmosphere of unrest was heightened by the Vietnam War. It was not until the early 1990s that the Iron Curtain collapsed, and the Cold War finally ended. While the 1960s were economically and culturally prosperous for Western Europe, those same years were tough for communist Eastern Europe, where the people still suffered from the aftermath of Stalin thwarting any attempts of artistic openness and creativity. As a result, certain efforts were made to build cultural bridges between West and East, including efforts that were significantly aided by Britten’s engagements. In his book Benjamin Britten and Russia, Cameron Pyke portrays the bridging of the vast gulf achieved through Britten’s interactions with the Soviet Union, drawing skillfully from historical and cultural contextualization, Britten’s and Pears’s personal accounts, interviews, musical scores, a series of articles about Britten published in the Soviet Union, and discussions of cultural and political figures of the time.1 In the seven chapters of his book, Pyke brings to light the nature of Britten’s six visits and offers detailed accounts of Britten’s affection for Russian music and culture. -

Pastiche for Piano on Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music

Pastiche For Piano On Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music Download pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2619 times and last read at 2021-09-28 10:12:03. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Method, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 sheet music has been read 3180 times. Opus calidoscopium in memory of sorabji op 2 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 19:02:59. [ Read More ] Pastiche 2017 Pastiche 2017 sheet music has been read 2663 times. Pastiche 2017 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 02:51:33. [ Read More ] Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 sheet music has been read 2729 times. Virtuoso etude no 4 in memory of sorabji nocturne op 1 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 05:00:02. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

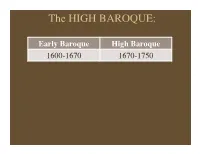

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba

COMPARISON AND CONTRAST OF PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF THE TUBA IN IGOR STRAVINSKY’S THE RITE OF SPRING, DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN D MAJOR, OP. 47, AND SERGEI PROKOFIEV’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 IN B FLAT MAJOR, OP. 100 Roy L. Couch, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2006 APPROVED: Donald C. Little, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Keith Johnson, Committee Member Brian Bowman, Coordinator of Brass Instrument Studies Graham Phipps, Program Coordinator of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Couch, Roy L., Comparison and Contrast of Performance Practice for the Tuba in Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 47, and Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100, Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2006, 46 pp.,references, 63 titles. Performance practice is a term familiar to serious musicians. For the performer, this means assimilating and applying all the education and training that has been pursued in a course of study. Performance practice entails many aspects such as development of the craft of performing on the instrument, comprehensive knowledge of pertinent literature, score study and listening to recordings, study of instruments of the period, notation and articulation practices of the time, and issues of tempo and dynamics. The orchestral literature of Eastern Europe, especially Germany and Russia, from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century provides some of the most significant and musically challenging parts for the tuba. -

Conducting from the Piano: a Tradition Worth Reviving? a Study in Performance

CONDUCTING FROM THE PIANO: A TRADITION WORTH REVIVING? A STUDY IN PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: MOZART’S PIANO CONCERTO IN C MINOR, K. 491 Eldred Colonel Marshall IV, B.A., M.M., M.M, M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2018 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor David Itkin, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Marshall IV, Eldred Colonel. Conducting from the Piano: A Tradition Worth Reviving? A Study in Performance Practice: Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C minor, K. 491. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2018, 74 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. Is conducting from the piano "real conducting?" Does one need formal orchestral conducting training in order to conduct classical-era piano concertos from the piano? Do Mozart piano concertos need a conductor? These are all questions this paper attempts to answer. Copyright 2018 by Eldred Colonel Marshall IV ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONDUCTING FROM THE KEYBOARD ............ 1 CHAPTER 2. WHAT IS “REAL CONDUCTING?” ................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 3. ARE CONDUCTORS NECESSARY IN MOZART PIANO CONCERTOS? ........................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 “Jeunehomme” (1777) ............................... 13 Piano Concerto No. 13 in C major, K. 415 (1782) ............................................................. 23 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 (1785) ............................................................. 25 Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. -

Magnus Lindberg 1

21ST CENTURY MUSIC FEBRUARY 2010 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2010 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Music Tech-1

Radnor Middle School Course Overview Music Technology I. Course Description Music Technology is offered as an eighth grade music elective, meeting three times a cycle. Students will be introduced to the study of music technology and music fundamentals. Areas of instruction will include instrument and equipment care, beginning level music literacy (reading and writing music), keyboard performance skills, music technology related history, concepts, terminology and experience with a variety of applications. II. Resources, Materials , Equipment • iMacs • GarageBand • Korg K61p MIDI Studio Contoller Keyboards • Student Journals III. Course Goals, Objectives (Essential Questions, Enduring Understandings) Students will be able to: 1. Accurately perform melody, harmony and rhythm parts of a composition and record the parts separately into the sequencer of the keyboard. 2. Accurately perform melody, harmony and rhythm parts of their own composition and record the parts separately into the sequencer of the keyboard. 3. Record multiple parts to an electronic “sound piece” using non-traditional instrument timbres and effects. 4. Orchestrate and perform three- and four-part synthesizer ensemble pieces within expected performance parameters for their individual levels of expertise. 5. Transfer sequenced MIDI files from the keyboard disk into the computer and, using appropriate software, edit needed corrections, format, and print out the composition. 6. Change instrumentation using an existing music composition stored as MIDI data; and alter tempo, range, and dynamics during the course of the piece, while still maintaining the original integrity of the composition. 7. Compose a four-part electronic sound piece using varied timbre (tone), texture, and dynamics of at least three minute length. Students may incorporate digitally recorded audio sounds into this piece. -

Magnus Lindberg Al Largo • Cello Concerto No

MAGNUS LINDBERG AL LARGO • CELLO CONCERTO NO. 2 • ERA ANSSI KARTTUNEN FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) 1 Al largo (2009–10) 24:53 Cello Concerto No. 2 (2013) 20:58 2 I 9:50 3 II 6:09 4 III 4:59 5 Era (2012) 20:19 ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello (2–4) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor 2 MAGNUS LINDBERG 3 “Though my creative personality and early works were formed from the music of Zimmermann and Xenakis, and a certain anarchy related to rock music of that period, I eventually realised that everything goes back to the foundations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – how could music ever have taken another road? I see my music now as a synthesis of these elements, combined with what I learned from Grisey and the spectralists, and I detect from Kraft to my latest pieces the same underlying tastes and sense of drama.” – Magnus Lindberg The shift in musical thinking that Magnus Lindberg thus described in December 2012, a few weeks before the premiere of Era, was utter and profound. Lindberg’s composer profile has evolved from his early edgy modernism, “carved in stone” to use his own words, to the softer and more sonorous idiom that he has embraced recently, suggesting a spiritual kinship with late Romanticism and the great masters of the early 20th century. On the other hand, in the same comment Lindberg also mentioned features that have remained constant in his music, including his penchant for drama going back to the early defiantly modernistKraft (1985). -

Music for the Piano Session Five

MUSIC FOR THE PIANO SESSION FIVE: “MOST LIKE AN ORCHESTRA,” 1860-1890 The above illustration for our fifth session a photograph of a modern concert grand piano – a full nine feet in length. By 1860 the piano was a fully developed instrument capable of filling large auditoriums with a wide range of sounds from very low to very high pitches, from very thin to very thick textures, and with many different kinds of sounds – all of which could be made softer or sustained over time by the use of foot pedals. PIANO DUET IMAGES We’re going to begin today’s session by looking at some images of piano duet playing – two people at one piano. As we have seen, this very popular genre of piano music began with Mozart and continued through the 19th century. Over time the image of two people making music at one piano became a powerful cultural image that illustrated, not only music-making, but social status, friendship and family solidarity as well. Here are some images that show various aspects of this once-popular kind of music-making. “MOST LIKE AN ORCHESTRA” There are many reasons why the piano became, and remained, the musical instrument of choice throughout the nineteenth century. We have already discussed several reasons: its reliability; its unique versatility to function as a solo instrument, to blend with other instruments, and to hold its own when contrasted with a full symphony orchestra. Add to this the simple fact that, by 1860, there were thousands of pianos in private homes and places of entertainment, and a vast repertoire of music of many types for both amateur and professional pianists to play. -

BèLa Bartã³k's Concerto for Orchestra

BELA BART6K'S CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA WORLDS CONTENDING: BELA, BARTOK'S'" CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA By REBECCA LEE GREEN, B.A.(Hons.Mus.) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University September 1987 MASTER OF ARTS (1987) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Music Criticism) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Worlds Contending: Bela Bart6k's Concerto for Orchestra AUTHOR: Rebecca Lee Green, B.A.(Hons.Mus.) (University of Western Ontario) SUPERVISOR: Professor Paul Rapoport NUMBER OF PAGES: ix, 192 ii Abstract Although the Concerto for Orchestra is Bart6k's largeS~ ! orchestral composition and one of the last works, it has received comparatively little attention in the scholarly literature. One reason for this may be the suggestion that it is artistically inferior, a compromise for the sake of financial success and public acceptance. This position is challenged through an examination of the circumstances surrounding the commission of the work, and its relation to Bart6k's biography. The main body of the thesis deals with the music itself in a comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of nine analytical approaches--the extent of serious criticism on the Concerto. Some of these analyses are more successful than others in discussing the work in a meaningful way. More importantly, the interaction of these analytical methods allowE for the emergence of a pattern in the music which is not evident to the same degree in any of the individual analyses. The interaction of these diverse approaches to the Concerto, which both confirm and contradict each other at various times, provides a wider analytical perspective through which it becomes possible to suggest that the Concerto for Orchestra is characterized by a dynamic principle of conflict or "Worlds Contending," from the title of a poem by Bartbk.