African-American Bassoonists and Their Representation Within the Classical Music Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

San Diego Symphony Frequently Asked Questions

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS San Diego Symphony performed its first concert on December 6, 1910 in the Grand Ballroom of the then-new U.S. Grant Hotel. Now, the San Diego Symphony has grown into one of the top orchestras in the country both artistically and financially. With a current budget of $20 million, the San Diego Sym- phony is now placed in the Tier 1 category as ranked by the League of American Orchestras. The San Diego Symphony owes a deep debt of gratitude to Joan and Irwin Jacobs for their extraordinary generosity, kindness and friendship. Their support and vision has overwhelmingly contributed to making the San Diego Symphony a leading force in San Diego’s arts and cultural community and a source of continuing civic pride for all San Diegans. Artistic Q. How many musicians are there in the San Diego Symphony? A. There are 82 full-time, contracted San Diego Symphony musicians. However, depending on the particular piece of music being performed, you may see more musicians on stage. These musicians are also auditioned and hired on a case-by-case basis. You may also see fewer musicians if the particular piece of music calls for less than the full complement. Q. How are the musicians selected? A. Musicians are selected through a rigorous audition process which is comprised of an orchestra committee and the music director. Open positions are rare. When an audition is held, it is common to have 100 to 150 musicians competing for the open position. Q. Where have the musicians received their training? A. -

A History of Tennessee

SECTION VI State of Tennessee A History of Tennessee The Land and Native People Tennessee’s great diversity in land, climate, rivers, and plant and animal life is mirrored by a rich and colorful past. Until the last 200 years of the approximately 12,000 years that this country has been inhabited, the story of Tennessee is the story of its native peoples. The fact that Tennessee and many of the places in it still carry Indian names serves as a lasting reminder of the significance of its native inhabitants. Since much of Tennessee’s appeal for settlers lay with the richness and beauty of the land, it seems fitting to begin by considering some of the state’s generous natural gifts. Tennessee divides naturally into three “grand divisions”—upland, often mountainous, East Tennessee; Middle Tennessee, with its foothills and basin; and the low plain of West Tennessee. Travelers coming to the state from the east encounter first the lofty Unaka and Smoky Mountains, flanked on their western slope by the Great Valley of East Tennessee. Moving across the Valley floor, they next face the Cumberland Plateau, which historically attracted little settlement and presented a barrier to westward migration. West of the Plateau, one descends into the Central Basin of Middle Tennessee—a rolling, fertile countryside that drew hunters and settlers alike. The Central Basin is surrounded on all sides by the Highland Rim, the western ridge of which drops into the Tennessee River Valley. Across the river begin the low hills and alluvial plain of West Tennessee. These geographical “grand divisions” correspond to the distinctive political and economic cultures of the state’s three regions. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 22/03/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 22/03/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars All Of Me - John Legend Love on the Brain - Rihanna EXPLICIT Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Blue Ain't Your Color - Keith Urban Hello - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond 24K Magic - Bruno Mars Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Piano Man - Billy Joel How Far I'll Go - Moana Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Jackson - Johnny Cash Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen My Way - Frank Sinatra Santeria - Sublime Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake He Stopped Loving Her Today - George Jones Summer Nights - Grease Turn The Page - Bob Seger At Last - Etta James Closer - The Chainsmokers Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding My Girl - The Temptations These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson A Whole New World -

Apr-May 1980

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 4 NO. 2 FEATURES: NEIL PEART As one of rock's most popular drummers, Neil Peart of Rush seriously reflects on his art in this exclusive interview. With a refreshing, no-nonsense attitude. Peart speaks of the experi- ences that led him to Rush and how a respect formed between the band members that is rarely achieved. Peart also affirms his belief that music must not be compromised for financial gain, and has followed that path throughout his career. 12 PAUL MOTIAN Jazz modernist Paul Motian has had a varied career, from his days with the Bill Evans Trio to Arlo Guthrie. Motian asserts that to fully appreciate the art of drumming, one must study the great masters of the past and learn from them. 16 FRED BEGUN Another facet of drumming is explored in this interview with Fred Begun, timpanist with the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C. Begun discusses his approach to classical music and the influences of his mentor, Saul Goodman. 20 INSIDE REMO 24 RESULTS OF SLINGERLAND/LOUIE BELLSON CONTEST 28 COLUMNS: EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 3 TEACHERS FORUM READERS PLATFORM 4 Teaching Jazz Drumming by Charley Perry 42 ASK A PRO 6 IT'S QUESTIONABLE 8 THE CLUB SCENE The Art of Entertainment ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Rick Van Horn 48 Odd Rock by David Garibaldi 32 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE The Technically Proficient Player JAZZ DRUMMERS WORKSHOP Double Time Coordination by Paul Meyer 50 by Ed Soph 34 CONCEPTS ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Drums and Drummers: An Impression Simple Percussion Modifications by Rich Baccaro 52 by David Ernst 38 DRUM MARKET 54 SHOW AND STUDIO INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 70 A New Approach Towards Improving Your Reading by Danny Pucillo 40 JUST DRUMS 71 STAFF: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Ronald Spagnardi FEATURES EDITOR: Karen Larcombe ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Mark Hurley Paul Uldrich MANAGING EDITOR: Michael Cramer ART DIRECTOR: Tom Mandrake The feature section of this issue represents a wide spectrum of modern percussion with our three lead interview subjects: Rush's Neil Peart; PRODUCTION MANAGER: Roger Elliston jazz drummer Paul Motian and timpanist Fred Begun. -

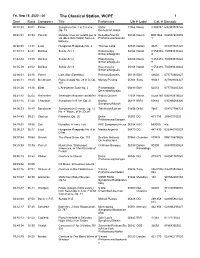

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, Sep 18, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 40:01 Paine Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Ulster 11966 Naxos 8.559747 636943974728 Op. 23 Orchestra/Falletta 00:42:3102:34 Puccini Quando m'en vo' soletta per la Netrebko/Vienna 09185 Decca B001566 028947829478 via (Musetta's Waltz) from La Philharmonic/Noseda 1 boheme 00:46:0513:38 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 Thomas Labe 04785 Dorian 9025 053473025128 01:01:13 42:21 Delibes Sylvia: Act 1 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 01:44:3419:55 Delibes Sylvia: Act 2 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 02:05:59 29:02 Delibes Sylvia: Act 3 Razumovsky 04166 Naxos 8.553338- 730099433822 Sinfonia/Mogrelia 9 02:36:0103:10 Ponce Little Star (Estrellita) Perlman/Sanders 00116 EMI 49604 077774960427 02:40:1119:45 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 28 in A, Op. Murray Perahia 05304 Sony 93043 827969304327 101 03:01:2619:16 Bizet L'Arlesienne Suite No. 2 Philharmonia 06499 EMI 62853 077776285320 Orchestra/Karajan 03:21:4205:03 Hoffstetter Serenade (Andante cantabile) Kodaly Quartet 11034 Naxos 8.558180 636943818022 03:27:45 31:38 Chausson Symphony in B flat, Op. 20 Boston 06919 BMG 60683 090266068326 Symphony/Munch 04:00:5316:47 Boccherini Symphony in D minor, Op. 12 Tafelmusik/Lamon 01856 DHM 7867 054727786723 No. 4 "House of the Devil" 04:18:40 09:21 Sibelius Finlandia, Op. 26 Berlin 00365 DG 413 755 28941375520 Philharmonic/Karajan 04:29:0129:56 Suk Pohadka, A Fairy Tale BBC Symphony/Hrusa 06384 BBC MM300 n/a 05:00:2706:17 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

Partitur Del 1 EN

Joakim Sandgren Sinfonietta for Chamber orchestra Instruments and mutes Flute Oboe (cloth) B-flat clarinet, also Bass clarinet (cloth) Bassoon (cloth) F horn C trumpet (straight, cup, harmon) Trombone (straight, cup) 1 Percussionist * Piano Violin 1 (practice mute) Violin 2 (practice mute) Viola (mute) Cello (mute) Double bass Duration 13 minutes Score in C * Percussion and mallets 2 snare drums without snares (nails, rod sticks) Vibraphone (elastic, medium hard mallets) 1 large muted bass drum (small drumstick, gope mallets) 1 small muted bass drum (small drumstick, gope mallets) 1 large tam-tam** (heavy soft mallets) 1 small tam-tam** (heavy soft mallets) 4 wood drums (heavy soft mallets) ** the large and small tam-tam should lie on thick blanket covering a table Joakim Sandgren h = 80 Sinfonietta 1997 - 1999 A molto legato, vibrato e dolcissimo ∞ ` ~~~~~~~~~ 1 with a cloth ` ~~~~~~~~~ ∞ I b œ . 4 ˙ b œ b œ ` ~~~~~~~~~ 2 œ b œ œ ˙ œ Œ b œ œ ‰ b œ œ b œ ≈ Œ œ œ œ ˙ œ Ó Ob l & 2 l b ˙ l ˙ n œ l l l π F π π l F π % F cold, stiff, and non vibrato molto l straight mute half valve II ¶ norm. valve, d.t. 1) £ l 2 half valve Œ . Œ ‰ –j ≠ ‰ Œ Ó Œ – ≠ Trp & 2 # ≠ – – – æ # – – – l - - - l -˙ #_ œj - l - – l –j - l - l π> > > > > >- > > l poco l F poco π l l l l molto legato, vibrato e dolcissimo (valve) l l l ~~ l l (valve) l cup mute ` (valve) 2) £ ` £ £ ` ~~~~ l _œ _œ_ œ ~~~~~ l l b_ ˙ l _œ _œ l _œ _œ l I2 b œ œ b ˙ œ b œ b œ œ œ Trb l B 2 Œ l Ó l Ó l Œ l Œ Ó l π π π π l F l F l l % F l l molto across the drum, up to down (from rim to rim) l 2 snare dr. -

Download the 2021-2022 Season Brochure Here (Pdf)

Pittsburg State University 2021-22 Solo & Chamber Music Series Order Form Call the PSU Department of Music: 620-235-4466 or complete this order form and mail to: Solo and Chamber Music Series • Department of Music 2021-22 Pittsburg State University • 1701 S. Broadway • Pittsburg, KS 66762-7511 I wish to attend the following concerts and have indicated type of ticket(s) requested. Solo & Chamber q Individual Concerts q$12 General Admission q$8 over 65/under 18 Music Series total number of tickets requested: ________ Please check q Friday, September 17 .........Poulenc Trio the boxes of q Friday, October 8 ...............Merz Trio Renewal. the individual q Friday, November 5 ............Alon Goldstein, piano As we begin to emerge from a year in which we were unable to host live concerts q Friday, January 28 .............Benjamin Appl, baritone you will be performances, this word takes on special significance. We are very excited about q Friday, February 18 ............Seraph Brass attending. q the prospect of renewing a tradition that has been such an important part of our Friday, April 1 .....................Jason Vieaux and Julien Labro cultural life for many decades. In assembling this year’s Solo & Chamber Music q q Series, we have turned to some of the profession’s most gifted artists, who q “Any Four Package” $41 General Admission $27 over 65/under 18 will bring an abundance of memorable moments to the stage of McCray Hall’s total number of tickets requested: ________ (a significant savings over individual prices) Sharon Kay Dean Recital Hall on six Friday evenings across the academic year. -

The Underground Railroad in Tennessee to 1865

The State of State History in Tennessee in 2008 The Underground Railroad in Tennesseee to 1865 A Report By State Historian Walter T. Durham The State of State History in Tennessee in 2008 The Underground Railroad in Tennessee to 1865 A Report by State Historian Walter T. Durham Tennessee State Library and Archives Department of State Nashville, Tennessee 37243 Jeanne D. Sugg State Librarian and Archivist Department of State, Authorization No. 305294, 2000 copies November 2008. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $1.77 per copy. Preface and Acknowledgments In 2004 and again in 2006, I published studies called The State of State History in Tennessee. The works surveyed the organizations and activities that preserve and interpret Tennessee history and bring it to a diverse public. This year I deviate by making a study of the Under- ground Railroad in Tennessee and bringing it into the State of State History series. No prior statewide study of this re- markable phenomenon has been produced, a situation now remedied. During the early nineteenth century, the number of slaves escaping the South to fi nd freedom in the northern states slowly increased. The escape methodologies and ex- perience, repeated over and over again, became known as the Underground Railroad. In the period immediately after the Civil War a plethora of books and articles appeared dealing with the Underground Railroad. Largely written by or for white men, the accounts contained recollections of the roles they played in assisting slaves make their escapes. There was understandable exag- geration because most of them had been prewar abolitionists who wanted it known that they had contributed much to the successful fl ights of a number of slaves, oft times at great danger to themselves. -

Monday Playlist

February 10, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “I pay no attention whatever to anybody's praise or blame. I simply follow my own feelings.” — WA Mozart Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Elgar The Spanish Lady Suite Guildhall String Ensemble/Salter RCA 7761 07863577612 00:14 Buy Now! Goldmark Sakuntala (Concert Overture), Op. 13 Budapest Philharmonic/Korodi Hungaroton 12552 N/A Trio in B flat for Clarinet, Horn & Piano, 00:32 Buy Now! Reinecke Campbell/Sommerville/Sharon EMI 81309 774718130921 Op. 274 Watkinson/City of London 01:00 Buy Now! Vivaldi Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 4 No. 4 Naxos 8.553323 730099432320 Sinfonia/Kraemer 01:09 Buy Now! Grieg Holberg Suite, Op. 40 English Chamber Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 K. & M. Labeque/Philharmonia 01:31 Buy Now! Bruch Concerto for Two Pianos, Op. 88a Philips 432 095 028943209526 Orchestra/Bychkov Nicolet/Netherlands Chamber 02:01 Buy Now! Bach, C.P.E. Flute Concerto in A minor Philips 442 592 028944259223 Orchestra/Zinman Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 02:26 Buy Now! Mozart Symphony No. 21 in A, K. 134 Philips 422 610 028942250222 Fields/Marriner 02:47 Buy Now! Handel Trio Sonata in F, Op. 2 No. 4 Heinz Holliger Wind Ensemble Denon 7026 N/A 03:01 Buy Now! Wagner Liebestod ~ Tristan und Isolde Price/Philharmonia/Lewis RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 03:09 Buy Now! Janacek Pohadka (Fairy Tale) Alisa and Vivian Weilerstein EMI Classics 73498 724357349826 03:22 Buy Now! Dvorak Symphony No. -

Valerie Coleman Has Been Making Her Mark As a Fine Flutist in Contemporary Music, the Flute Is Not Her Only, Or Even Her Primary, Medium of Expression

December 2008 VALERI E COLEMAN: REVITALIZING THE WOODWIND QUINTET by Peter Westbrook Reprinted with permission from the spring 2008 issue of The Flutist Quarterly. lute performance, composing, Imani Winds, and the desire to bring great music to margin- Falized communities are among the passions that drive this determined musician. As her ensemble enters its second decade, the self-described “average flutist” is sowing rewards for her steady, hard work. Although Valerie Coleman has been making her mark as a fine flutist in contemporary music, the flute is not her only, or even her primary, medium of expression. For the past 10 years, Coleman’s hand has been at the helm of the award-winning woodwind quintet Imani Winds, which provides an outlet for her not only as flutist but also as composer, arranger, and visionary. In Concert The success of the group as it embarks on its second decade—thus far it has Imani Winds received a Grammy nomination, in 2006, Valerie Coleman, flute; Toyin Spellman-Diaz, oboe; and two ASCAP/Chamber Music America Mariam Adam, clarinet; Jeff Scott, French horn; Monica Ellis, bassoon awards—is a testament to that vision. For as long as Coleman can remember, Sunday, December 14, 2008, 5:30 pm flute performance and composition have Yamaha Piano Salon, 689 Fifth Avenue vied equally for her attention. When I (entrance on 54th Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues) asked her if she thought of herself as a flutist/composer or composer/flutist she Afro Blue Mongo Santamaria (1917-2003) could not make a choice; both are very arr. -

About Imani Winds

Presents Imani Winds Rhythm and Song The Influence of the African Diaspora on Classical Music Wednesday, April 30, 2008 10am in Bowker Auditorium Study Guides for Teachers are also available on our website at www.fineartscenter.com - select For School Audiences under Education, then select Resource Room. Please fill out our online surveys at http://www.umass.edu/fac/centerwide/school/index.html for the Registration Process and each Event. Thank you! The Arts and Education Program of the Fine Arts Center is sponsored by ABOUT IMANI WINDS Formed in 1997, IMANI WINDS is a woodwind quintet of young, hip, and adventurous classically‐trained musicians of color. Demonstrating that classical music is much more diverse that usually thought of, Imani Winds performs compositions that push the boundaries of a traditional wind‐quintet repertoire. They play jazz, contemporary music, spirituals, works by African and Latin‐American composers and European compositions with a worldly influence. They strive to illuminate the connection between culture from the African Diaspora and classical music. Imani Winds has carved out a distinct presence in the classical music world for their dynamic playing, culturally poignant programming and inspirational outreach programs, which they have brought to many communities throughout the country. THE MUSICIANS Valerie Coleman, flute A native of Kentucky, flutist and composer Valerie began her music studies in third grade. By the age of fourteen, she had written three symphonies and had won several local and state competitions. Valerie is the founder of Imani Winds and an active composer and educator. Toyin Spellman‐Diaz, oboe Toyin started her musical career as a flute player in her middle school band in Washington, DC, but when she noticed there were dozens of flute players and only two oboe players, she decided to switch to the oboe—and hoped she would be given more solos as a result! Toyin grew to love the oboe, excelled at playing, and had the opportunity to perform internationally at a young age.