Cyrenaica Author(S): JW Gregory Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

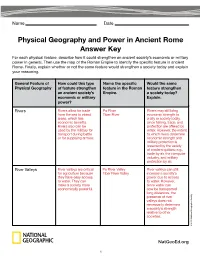

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

CHAP'IERTWO THE LYCIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography and communications in Lycia1 Lycia lies on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, between Caria and Pam phylia. At the period of its smallest extent, at the time of the Persian con quest, the Lycian state covered an area comparable in size to Attica, ex tending over most of the territory of the Xanthos valley, probably as far north as Araxa, more than forty kilometres away from Xanthos, and nearly fifty from the Mediterranean; Bryce has argued that to Homer 'Lycia' meant no more than the Xanthos valley. 2 At its largest, under Perikle of Limyra (pp. 154-70), the Lycian state was comparable in size to the south ern Peloponnese (i.e. Laconia and Messenia), stretching from Phaselis in the east to Telemessos in the north-west, nearly a hundred and thirty kilo metres as the crow flies, and included a large section of southern Milyas, if not all of it (p. 20). It is separated from its neighbours by high mountains which hampered movement in antiquity. 3 This remoteness continued into modern times-when Bean first visited the area in 1946 he found a country where tractors were unknown, and: When I asked, 'What do you do in the winter?', the answer was, 'We sit'.4 Three great chains determine access to and within Lycia. In the west two spurs of the western Tauros, the Boncuk Daglan and the Baba Dag1 (this latter being ancient Mt. Kragos and Mt. Antikragos) restrict access to Ly cia to the pass between them, east of Telemessos. -

A New Geography of European Power?

A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? EGMONT PAPER 42 A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? James ROGERS January 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont - The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1714 7 D/2011/4804/19 U 1547 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. -

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya BBQPERTY OF U.S.GW«r..GlCAL SURVEY JRENTON, NEW JEST.W Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya By W. W. DOYEL and F. J. MAGUIRE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract _ _______________-__--__-_______--__--_-__---_-------_--- Bl Introduction______-______--__-_-____________--------_-----------__ 1 Location and extent of area-----_______----___--_-------------_- 1 Purpose and scope of investigation---______-_______--__-------__- 3 Acknowledgments __________________________-__--_-----_--_____ 3 Geography___________--_---___-_____---____------------_-___---_- 5 General features.._-_____-___________-_-_____--_-_---------_-_- 5 Topography and drainage_______________________--_-------.-_- 6 Climate.____________________.__----- - 6 Geology____________________-________________________-___----__-__ 8 Ground water____._____________-____-_-______-__-______-_--_--__ 10 Bengasi municipal supply_____________________________________ 12 Other water supplies___________________-______-_-_-___-_--____- 14 Test drilling....______._______._______.___________ 15 Conclusions. -

The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century

The AAG Review of Books ISSN: (Print) 2325-548X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrob20 The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Jörn Seemann To cite this article: Jörn Seemann (2016) The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, The AAG Review of Books, 4:3, 159-161, DOI: 10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 Published online: 07 Jul 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 312 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrob20 The AAG Review OF BOOKS The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Mark Monmonier, ed. Chicago, document how all cultures of all his- IL: University of Chicago Press, torical periods represented the world 2015. 1,960 pp., set of 2 using maps” (Woodward 2001, 28). volumes, 805 color plates, What started as a chat on a relaxed 119 halftones, 242 line drawings, walk by these two authors in Devon, England, in May 1977 developed into 61 tables. $500.00 cloth (ISBN a monumental historia cartographica, 978-0-226-53469-5). a cartographic counterpart of Hum- boldt’s Kosmos. The project has not Reviewed by Jörn Seemann, been finished yet, as the volumes on Department of Geography, Ball the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- State University, Muncie, IN. tury are still in preparation, and will probably need a few more years to be published. -

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in Their Contexts and As Evidence of His World Map

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in their Contexts and as Evidence of his World Map Christopher B. Krebs American Journal of Philology, Volume 139, Number 1 (Whole Number 553), Spring 2018, pp. 93-122 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ajp.2018.0003 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687618 Access provided at 25 Oct 2019 22:25 GMT from Stanford Libraries THE WORLD’S MEASURE: CAESAR’S GEOGRAPHIES OF GALLIA AND BRITANNIA IN THEIR CONTEXTS AND AS EVIDENCE OF HIS WORLD MAP CHRISTOPHER B. KREBS u Abstract: Caesar’s geographies of Gallia and Britannia as set out in the Bellum Gallicum differ in kind, the former being “descriptive” and much indebted to the techniques of Roman land surveying, the latter being “scientific” and informed by the methods of Greek geographers. This difference results from their different contexts: here imperialist, there “cartographic.” The geography of Britannia is ultimately part of Caesar’s (only passingly and late) attested great cartographic endeavor to measure “the world,” the beginning of which coincided with his second British expedition. To Tony Woodman, on the occasion of his retirement as Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics at the University of Virginia, in gratitude. IN ALEXANDRIA AT DINNER with Cleopatra, Caesar felt the sting of curiosity. He inquired of “the linen-wearing Acoreus” (linigerum . Acorea, Luc. 10.175), a learned priest of Isis, whether he would illuminate him on the lands and peoples, gods and customs of Egypt. Surely, Lucan has him add, there had never been “a visitor more capable of the world” than he (mundique capacior hospes, 10.183). -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

THE GEOGRAPHY of GALATIA Gal 1:2; Act 18:23; 1 Cor 16:1

CHAPTER 38 THE GEOGRAPHY OF GALATIA Gal 1:2; Act 18:23; 1 Cor 16:1 Mark Wilson KEY POINTS • Galatia is both a region and a province in central Asia Minor. • The main cities of north Galatia were settled by the Gauls in the third cen- tury bc. • The main cities of south Galatia were founded by the Greeks starting in the third century bc. • Galatia became a Roman province in 25 bc, and the Romans established colonies in many of its cities. • Pamphylia was part of Galatia in Paul’s day, so Perga and Attalia were cities in south Galatia. GALATIA AS A REGION and their families who migrated from Galatia is located in a basin in north-cen- Thrace in 278 bc. They had been invited tral Asia Minor that is largely flat and by Nicomedes I of Bithynia to serve as treeless. Within it are the headwaters of mercenaries in his army. The Galatians the Sangarius River (mode rn Sakarya) were notorious for their destructive and the middle course of the Halys River forays, and in 241 bc the Pergamenes led (modern Kızılırmak). The capital of the by Attalus I defeated them at the battle Hittite Empire—Hattusha (modern of the Caicus. The statue of the dying Boğazköy)—was in eastern Galatia near Gaul, one of antiquity’s most noted the later site of Tavium. The name Galatia works of art, commemorates that victo- derives from the twenty thousand Gauls ry. 1 The three Galatian tribes settled in 1 . For the motif of dying Gauls, see Brigitte Kahl, Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010), 77–127. -

How Did Geography Help Rome Rise to Power the Roman Empire Dominated Most of Europe and Much of Africa and the Middle East for Centuries

How did Geography Help Rome Rise to Power The Roman Empire dominated most of Europe and much of Africa and the Middle East for centuries. So great was the empire that it influences geopolitics even today. Often overlooked is the role that geography played in the great city's rise to power. Several geographic advantages helped Rome to grow and ultimately dominate the known world. Protection From Invasion Two mountain ranges, the Alps and the Apennines, helped to protect Rome from invasion. The Apennines divide the Italian peninsula in half and, according to SPQR Online, allowed the Romans to mass forces for counter-attack whenever they were threatened. Any army attempting to attack Rome would be at risk of attack from the other side of the mountains. The Alps, located on the northern border of modern-day Italy, seal off the peninsula from the rest of Europe during winter. This natural roadblock protected Rome from outside invasions by forcing attackers to move slowly through narrow passes, giving the Romans time to respond. Fertile Land Rich volcanic soil makes the Po and Tiber river valleys ideally suited for agriculture. Historian Mike Anderson notes that volcanic ash made the soil near Rome some of the best in all of Europe. Rome attracted new settlers during its rise to power due to its agricultural potential, according to Collins Hill High School teacher Julie Smith. The Roman population grew quickly, thanks to surplus production of grains, olives and other crops. The extra population later helped Rome's military expansion by providing a large supply of troops. -

2.1 Libya Port Assessment Port Assessment Overview

2.1 Libya Port Assessment Port Assessment Overview There are four main commercial seaports in western Libya: the port of Tripoli, the port of Al Khoms, the port of Misratah and the port of Zwarah. In eastern Libya there are two main seaports: Benghazi and Tobruk. The Port of Tripoli is the principal port in Tripoli, the capital of Libya, and one of the oldest ports in the Mediterranean. It is managed and operated by the "Libyan Ports Company", and handles different types of products including containerized and bulk cargoes, livestock, chemical and oils, etc. The port is protected by two breakwaters of 2000 and 700 meters, and the harbour covers about 500 hectares, and can accommodate vessels up to 190 meters long with maximum draft of 10.5 meters. The port’s maximum annual capacity is about 4 M Tons. Al Khoms Port is a small port for bulk carriers, general containers, livestock, car carriers, and oil and chemical items. It has an entrance channel of 16 meters depth, and an anchorage with a depth of 10.5 to 11.5 meters. The port itself consists of nine medium sized berths (numbers 12 to 19) with lengths ranging from 75 to 530 meters, and maximum drafts ranging from 10.5 to 11.5 meters depending on the berth. The port is well organized, functioning, and had no security breaches reported in 2018. Misratah Port is connected directly to the main motorway by a heavy transportation road (that does not cross the city centre). The port is under development and has a target to add more berths with total lengths of 2,250m, and drafts of 13m, in order to receive 4 million containers per year.