Roman Views of the Chinese in Antiquity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE: Pomponius Mela's World Map DATE: A.D. 37 AUTHOR: Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela’s World View #116 TITLE: Pomponius Mela’s World Map DATE: A.D. 37 AUTHOR: Pomponius Mela DESCRIPTION: The images in this monograph show attempts at reconstruction of the world view of the earliest Roman geographer Pomponius Mela, who, although of Spanish birth, wrote a brief work which agrees in most of its views with the great Greek writers from Eratosthenes (#112) to Strabo (#115). However, Mela departs from the traditional ancient concept by asserting that in the southern temperate zone dwelt inhabitants who were inaccessible to Europeans because of the Torrid Zone that intervened. His knowledge of the characters of Western Europe and the British Isles was clearer than that of the Greek writers, and he was the first to name the Orcades [Orkney Islands]. The great Roman historian Pliny quoted Mela as an authority. The first-century author Pomponius Mela enjoyed a long- standing reputation in geographical matters, given Pliny’s praise of him in the Natural History. But no text by Mela was known until the 1330s, when Petrarch discovered his De chorographia [On Chorography, or Descriptive Geography] in Avignon. Mela did not include a map in his text, but it has been suggested that he had in mind the map of the known world that Agrippa (#118) had started and Augustus completed. Displayed in the Porticus Vipsania in Rome, this map was known as chorographia, a name possibly recalled by the title of Mela’s text. Petrarch was fascinated with Mela’s brief and engaging text and had copies made for fellow humanists, including Giovanni Boccaccio, facilitating the wide circulation of the manuscript for almost a century, until it was printed in Milan in 1471. -

A Historical Review of the Silk Road

International Journal of New Developments in Engineering and Society ISSN 2522-3488 Vol. 5, Issue 1: 47-49, DOI: 10.25236/IJNDES.2021.050110 A historical review of the Silk Road Yurui Xu Nanjing Foreign Language School, Nanjing, Jiangsu, 210009, China Abstract: During the process of trade, some factors can decide whether the trade can continue fluently and which side has more dominance. This essay will focus on the trade of ancient China and the Silk road to discuss which factor has an important influence on the trade and explain the background and reasons. When ancient China was in strong period, like the early period of Tang dynasty (China at that time was one of the most powerful countries among the world), Chinese government had more trade dominance as they didn’t necessarily rely on the goods of foreign merchants. However, with the decline of Chinese power, its trade dominance decrease at the same time and the government gradually lost its control of the Silk Road. Consequently, Chinese government began to develop other trade routes-- the Maritime Silk Road. Keywords: Trade dominance; Control of The Silk Road; Changes of power of Ancient China; Maritime Silk Road 1. Introduction In this ever-changing world, China continues to embrace the world with its opening up policy and defend globalization. Since 2013 the Belt and Road Initiative has attracted a lot of investors outside of China. From South Asia to Western Europe, 65 countries have signed for the project, which connects China with partners all the way to Europe. The idea of BRI originates from the ancient Silk Road where merchants from the Han Dynasty traded with partners mainly from Central Asia. -

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society Heather Langford Theses submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Centre of Asian Studies University of Adelaide May 2009 ii Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Centre of Asian Studies School of Humanities and Social Sciences Adelaide University 2009 iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. Literature Review..............................................................................13 1.2. Chapter summary ..............................................................................17 1.3. Conclusion ........................................................................................19 2. Background .......................................................................................20 2.1. Pre Han History.................................................................................20 2.2. Qin Dynasty ......................................................................................24 2.3. The Han Dynasty...............................................................................25 2.3.1. Trade with the West............................................................................. 30 2.4. Conclusion ........................................................................................32 3. Textiles and Technology....................................................................33 -

ANNALS UNABRIDGED Read by David Timson

TACITUS NON- FICTION ANNALS UNABRIDGED Read by David Timson Beginning at the end of Augustus’s reign, Tacitus’s Annals examines the rules of the Roman emperors from Tiberius to Nero (though Caligula’s books are lost to us). Their dramas and scandals are brought fully under the spotlight, as Tacitus presents a catalogue of their murders, atrocities, sexual improprieties and other vices in no unsparing terms. Debauched, cruel and paranoid, they are portrayed as being on the verge of madness. Their wars and battles, such as the war with the Parthians, are also described with the same scrutinising intensity. Tacitus’s last major historical work, the Annals is an extraordinary glimpse into the pleasures and perils of a Roman leader, and is considered by many to be a masterpiece. David Timson has made over 1,000 broadcasts for BBC Radio Drama. For Naxos AudioBooks he has written The History of Theatre, an award-winning Total running time: 18:11:34 production read by Derek Jacobi, and directed four Shakespeare plays including View our catalogue online at n-ab.com/cat King Richard III (with Kenneth Branagh). He has also read the entire Sherlock Holmes canon and Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. 1 The Annals of Imperial Rome 14:18 27 The emperor opposed the motion. ‘Although,’ he said… 11:46 2 On the first day of the senate he allowed nothing to… 14:33 28 Book 4 15:05 3 Great too was the Senate’s sycophancy to Livia. 14:31 29 The same honours were decreed to the memory of… 14:28 4 As soon as he entered the entrenchments… 12:30 30 -

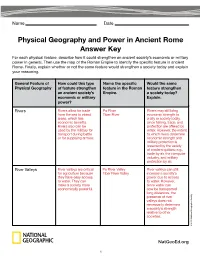

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

China's Southwestern Silk Road in World History By

China's Southwestern Silk Road in World History By: James A. Anderson James A. Anderson, "China's Southwestern Silk Road in World History," World History Connected March 2009 http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/6.1/anderson.html Made available courtesy of University of Illinois Press: http://www.press.uillinois.edu/ ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from the University of Illinois Press. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document.*** As Robert Clark notes in The Global Imperative, "there is no doubt that trade networks like the Silk Road made possible the flourishing and spread of ancient civilizations to something approximating a global culture of the times."1 Goods, people and ideas all travelled along these long-distance routes spanning or circumventing the vast landmass of Eurasia. From earliest times, there have been three main routes, which connected China with the outside world.2 These were the overland routes that stretched across Eurasia from China to the Mediterranean, known collectively as the "Silk Road"; the Spice Trade shipping routes passing from the South China Sea into the Indian Ocean and beyond, known today as the "Maritime Silk Road"; and the "Southwestern Silk Road," a network of overland passages stretching from Central China through the mountainous areas of Sichuan, Guizhou and Yunnan provinces into the eastern states of South Asia. Although the first two routes are better known to students of World History, the Southwestern Silk Road has a long ancestry and also played an important role in knitting the world together. -

THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

CHAP'IERTWO THE LYCIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography and communications in Lycia1 Lycia lies on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, between Caria and Pam phylia. At the period of its smallest extent, at the time of the Persian con quest, the Lycian state covered an area comparable in size to Attica, ex tending over most of the territory of the Xanthos valley, probably as far north as Araxa, more than forty kilometres away from Xanthos, and nearly fifty from the Mediterranean; Bryce has argued that to Homer 'Lycia' meant no more than the Xanthos valley. 2 At its largest, under Perikle of Limyra (pp. 154-70), the Lycian state was comparable in size to the south ern Peloponnese (i.e. Laconia and Messenia), stretching from Phaselis in the east to Telemessos in the north-west, nearly a hundred and thirty kilo metres as the crow flies, and included a large section of southern Milyas, if not all of it (p. 20). It is separated from its neighbours by high mountains which hampered movement in antiquity. 3 This remoteness continued into modern times-when Bean first visited the area in 1946 he found a country where tractors were unknown, and: When I asked, 'What do you do in the winter?', the answer was, 'We sit'.4 Three great chains determine access to and within Lycia. In the west two spurs of the western Tauros, the Boncuk Daglan and the Baba Dag1 (this latter being ancient Mt. Kragos and Mt. Antikragos) restrict access to Ly cia to the pass between them, east of Telemessos. -

The New Silk Roads: China, the U.S., and the Future of Central Asia

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY i CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION The New Silk Roads: China, the U.S., and the Future of Central Asia October 2015 Thomas Zimmerman NEW YORK UNIVERSITY CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION The world faces old and new security challenges that are more complex than our multilateral and national institutions are currently capable of managing. International cooperation is ever more necessary in meeting these challenges. The NYU Center on International Cooperation (CIC) works to enhance international responses to conflict, insecurity, and scarcity through applied research and direct engagement with multilateral institutions and the wider policy community. CIC’s programs and research activities span the spectrum of conflict, insecurity, and scarcity issues. This allows us to see critical inter-connections and highlight the coherence often necessary for effective response. We have a particular concentration on the UN and multilateral responses to conflict. Table of Contents The New Silk Roads: China, the U.S., and the Future of Central Asia Thomas Zimmerman Acknowledgments 2 Foreword 3 Introduction 6 The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor 9 Chinese Engagement with Afghanistan 11 Conclusion 18 About the Author 19 Endnotes 20 Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences (SASS) for its support during the research and writing of this paper, particularly Professor Pan Guang and Professor Li Lifan. I would also like to thank Director Li Yihai, and Sun Weidi from the SASS Office for International Cooperation, as well as Vice President Dong Manyuan, and Professor Liu Xuecheng of the China Institute for International Studies. This paper benefited greatly from the invaluable feedback of a number of policy experts, including Klaus Rohland, Andrew Small, Dr. -

Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uyghur Manuscripts from Bulayïq*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uyghur Manuscripts from Bulayïq Syriac, Sogdian and Old Uyghur Manuscripts from Bulayïq * Erica C.D. Hunter Department for the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, The German Turfan Expedition conducted 4 campaigns at the Turfan Oasis between 1902 and 1914 bringing 40,000 fragments in 20 scripts and 22 languages back to Berlin. During the 2nd and 3rd seasons (1904 – 1907), a library was unearthed at the monastery site of Shuïpang near Bulayïq yielding ca.1100 fragments written in Syriac script and covering 3 major languages: Syriac, Sogdian and old Uyghur. Several fragments in New Persian and a Middle Persian (Pahlavi) Psalter were also found[1]. Small quantities of Christian texts, in Syriac, Sogdian, Uyghur and Persian, were discovered at other sites in the Turfan oasis (Astana, Qocho, Qurutqa and Toyoq). Regrettably, there are scant remarks about the excavation of the archive by Theodor Bartus at Bulayïq, north of the city of Turfan, a site which von Le Coq had previously visited. Talking about his colleague’s visit, von Le Coq stated in his book Auf Hellas Spuren in Ostturkistan: “er hat ... in dem schauerlich zerstörten Gemäuer eine fabelhafte Ausbeute christlicher Handschriften ausbegraben” (he excavated ... in the extremely ruined walls an amazing Christian manuscript”)[2]. The Syriac - script fragments from Turfan shed invaluable light onto the eastward missionary expansion of the Church of the East whose dioceses extended into Central Asia, China and Mongolia up till the 14th century, not only attesting the nature and expression of worship (liturgy etc) that was conducted, but also revealing how this branch of Eastern Christianity interacted with the local languages and cultures of its diverse congregations.