Modernist Heritage Conservation: an Evaluation of Theories and Current Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture at a First Glance Is Published by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science

... Contents Section 1 Introduction 7 Section 2 General Outline 9 2.1 Geography and language 9 2.2 Population and demographics 9 2.3 The role of the city 11 2.4 Organisation of government 13 2.5 Politics and society 14 2.6 Economic and social trends 15 Section 3 Cultural Policy 19 3.1 Historical perspective 19 3.2 Division of roles in tiers of government in funding of culture 20 3.3 Government spending on culture 21 3.3.1 Central government’s culture budget for 2013-2016 21 3.3.2 Municipal spending on culture 22 3.3.3 Impact of cuts on funded institutions 25 3.4 Cultural amenities: spread 26 3.5 Priority areas for the Dutch government 29 3.5.1 Cultural education and participation in cultural life 29 3.5.2 Talent development 30 3.5.3 The creative industries 30 3.5.4 Digitisation 31 3.5.5 Entrepreneurship 31 3.5.6 Internationalisation, regionalisation and urbanisation 32 3.6 Funding system 33 3.7 The national cultural funds 34 3.8 Cultural heritage 35 3.9 Media policy 38 Section 4 Trends in the culture sector 41 4.1 Financial trends 41 4.2 Trends in offering and visits 2009-2014 44 4.2.1 Size of the culture sector 44 4.2.2 Matthew effects? 45 4.3 Cultural reach 45 4.3.1 More frequent visits to popular performances 47 4.3.2 Reach of the visual arts 47 4.3.3 Interest in Dutch arts abroad 51 4.3.4 Cultural tourism 53 4.3.5 Culture via the media and internet 54 4.4 Arts and heritage practice 57 4.5 Cultural education 59 5 1 Introduction Culture at a first Glance is published by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. -

Must-Sees and Icons of the City 2018

Cover: Markthal, Iris van den Broek van Markthal, Iris Cover: Must-sees and icons of the city 2018 Claire Droppert 1 Rotterdam Centraal Rotterdam Central Station (Team CS, 2014) is one of the most iconic architectural sites MUST DO! in Rotterdam. The roof over the tracks is Need time to take covered in solar panels and the striking hall in this architectural roof points towards the city centre. A number masterpiece? Relax of historic elements from the former station with a cup of coffee building (1957) by Sybold van Ravesteyn next door at Engels have been re-used, like the original clock restaurant, or take in the front façade and the letters spelling the lift in the Groot out ‘Centraal Station’. In the main hall you Handelsgebouw to the 7th floor for a can find several shops, information about beautiful view of public transport and the Rotterdam Tourist Rotterdam Central Information. If you’re looking for original Station. souvenirs, don’t miss shopping at ‘Love Rotterdam. Gifts, Food & More.’ 2 Markthal You’ll find an indoor market hall in various world-class cities, but the combination with luxury housing makes Rotterdam’s Market Hall (MVRDV & INBO, 2014) the first of its kind. The apartments are arched over the DID YOU KNOW? food market in a horseshoe configuration. One of the country’s The main hall houses the market itself, as biggest outdoor well as shops, various restaurants and a four- markets is held on storey car park situated below. Look up to the large square enjoy the massive artwork sprawled across (Binnenrotte) in front of the Markthal the ceiling: the ‘Horn of Plenty’. -

News and Events in from Holland This Autumn Current and Future Events

News and Events in from Holland this Autumn Current and future events & exhibitions Current David Cronenberg - The Exhibition, EYE, Amsterdam Until 14 September 2014 EYE presents a major exhibition focusing on director David Cronenberg, who acquired cult status with his idiosyncratic films about the relationship between body, mind, technology and mass media. Curated and organized by the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), the exhibition explores Cronenberg’s world through the main themes of his films: the physical and psychological transformation of his protagonists. Highlights of this exhibition include the weird and wonderful special effects items from Cronenberg’s films, together with bizarre props, set photos and original costumes. Cronenberg has worked with famous actors such as Jeff Goldblum, Keira Knightley, Holly Hunter, Jude Law, Jeremy Irons and Robert Pattinson, whom he challenged to push the boundaries of their profession. Fashion, the musical, Centraal Museum, Utrecht Until 30 November 2014 Fashion illustrator Piet Paris is guest curator for Centraal Museum. More than 150 items are selected by Piet Paris from the Centraal Museum collection and presented in a surprising manner: as scenes in a musical. Taking the visitor from backstage and the red carpet to – eventually- the stage, he shows more than fifty looks by designers such as Comme des Garçons, Maison Martin Margiela, Iris van Herpen, Viktor & Rolf, but also 17th and 18th century costumes. Paris wants to show fashion in context, and not isolation. He combines fashion with objects, which he actually puts to use: ticking clocks, flower-filled vases and burning lights. He breaks the anonymity of the mannequin by giving each one a complete outfit, as well as a face drawn by the illustrator himself. -

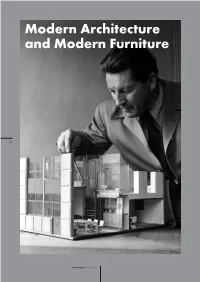

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture 14 docomomo 46 — 2012/1 docomomo46.indd 14 25/07/12 11:13 odern architecture and Modern furniture originated almost during the same period of time. Modern architects needed furniture compatible with their architecture and because Mit was not available on the market, architects had to design it themselves. This does not only apply for the period between 1920 and 1940, as other ambitious architectures had tried be- fore to present their buildings as a unit both on the inside and on the outside. For example one can think of projects by Berlage, Gaudí, Mackintosh or Horta or the architectures of Czech Cubism and the Amsterdam School. This phenomenon originated in the 19th century and the furniture designs were usually developed for the architect’s own building designs and later offered to the broader consumer market, sometimes through specialized companies. This is the reason for which an agree- ment between the architect and the commissioner was needed, something which was not always taken for granted. By Otakar M á c ˆe l he museum of Czech Cubism has its headquarters designed to fit in the interior, but a previous epitome of De in the Villa Bauer in Liboˇrice, a building designed Stijl principles that culminated in the Schröderhuis. Tby the leading Cubist architect Jiˆrí Gocˆár between The chair was there before the architecture, which 1912 and 1914. In this period Gocˆár also designed Cub- was not so surprising because Rietveld was an interior ist furniture. Currently the museum exhibits the furniture designer. The same can be said about the “father” of from this period, which is not actually from the Villa Bauer Modern functional design, Marcel Breuer. -

In Case of Architectural Design Critique and Praise of Case-Based Design in Architecture

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN FACULTEIT TOEGEPASTE WETENSCHAPPEN DEPARTEMENT ARCHITECTUUR, STEDENBOUW EN RUIMTELIJKE ORDENING Kasteel van Arenberg, B-3001 Leuven In case of architectural design Critique and praise of Case-Based Design in architecture Jury: Proefschrift voorgedragen tot Voorzitter Prof. Joos Vandewalle, vice-decaan het behalen van het doctoraat Prof. Herman Neuckermans, promotor in de toegepaste wetenschappen Prof. André Loeckx Prof. Jan Schreurs door Prof. Johan Wagemans Prof. Albert Dupagne (Université de Liège) Ann Heylighen Prof. Rivka Oxman (Technion Haifa) UDC 72.011 Mei 2000 Katholieke Universiteit Leuven – Faculteit Toegepaste Wetenschappen Kasteel van Arenberg, B-3001 Leuven (Belgium) Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm, elektronisch of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande toestemming van de uitgever. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. D/2000/7515/17 ISBN 90-5682-248-9 For my grandmother Acknowledgements Five years ago, I had to decide on a subject for my graduate’s thesis. Professor Herman Neuckermans made the suggestion to have a look at Case-Based Design, at that time a ‘hot topic’ in the field of CAAD. Computers were not exactly what I would call my cup of tea, but I nevertheless accepted his suggestion – not in the last place because it would enable me to spend one semester at the ETH in Zürich. Although the thesis became an unqualified success in terms of scores, it left me with an uneasy feeling. -

The Urban and Cultural Climate of Rotterdam Changed Radically Between 1970 and 2000. Opinions Differ About What the Most Importa

The urban and cultural climate of Rotterdam changed radically between 1970 and 2000. Opinions differ about what the most important changes were, and when they occurred. Imagine a Metropolis shows that it was first and foremost a new perspective on Rotterdam that stimulated the development of the city during this period. If the Rotterdam of 1970 was still a city with an identity crisis that wanted to be small rather than large and cosy rather than commercial, by 2000 Rotterdam had the image of the most metropolitan of all Dutch cities. Artists and other cultural practitioners – a group these days termed the ‘creative class’ – were the first to advance this metropolitan vision, thereby paving the way for the New Rotterdam that would begin to take concrete shape at the end of the 1980s. Imagine a Metropolis goes on to show that this New Rotterdam is returning to its nineteenth-century identity and the developments of the inter-war years and the period of post-war reconstruction. For Nina and Maria IMAGINE A METROPOLIS ROTTERDAM’S CREATIVE CLASS, 1970-2000 PATRICIA VAN ULZEN 010 Publishers, Rotterdam 2007 This publication was produced in association with Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam. On February 2, 2007, it was defended as a Ph.D. thesis at the Erasmus University, Rotterdam. The thesis supervisor was Prof. Dr. Marlite Halbertsma. The research and this book were both made possible by the generous support of the Faculty of History and Arts at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, G.Ph. Verhagen-Stichting, Stichting Kunstpublicaties Rotterdam, J.E. Jurriaanse Stichting, Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds Zuid-Holland and the Netherlands Architecture Fund. -

Old and New in Adaptive Reuse of Modern Industrial Heritage Ava Moshaver Ryerson University

Ryerson University Digital Commons @ Ryerson Theses and dissertations 1-1-2011 Re Architecture: Old and New In Adaptive Reuse of Modern Industrial Heritage Ava Moshaver Ryerson University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/dissertations Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Moshaver, Ava, "Re Architecture: Old and New In Adaptive Reuse of Modern Industrial Heritage" (2011). Theses and dissertations. Paper 1421. This Thesis Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Ryerson. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ryerson. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE ARCHITECTURE: Old and New In Adaptive Reuse of Modern Industrial Heritage by Ava Moshaver B.Arch Sci.,Ryerson University 2009 A Design Thesis Project presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in the Program of Architecture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2012 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis project. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis project to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis project by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT Adaptation of existing buildings for new functions is not a new phenomenon: the theoretical approach towards adaptive reuse was well established and theoretically formulated as early as at the beginning of the 19th century. -

Patrimoine Mondial 23 COM

Patrimoine Mondial 23 COM Distribution limitée WHC-99/CONF.209/10 Paris, le 5 octobre 1999 Original : anglais / français ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Vingt-troisième session Marrakech, Maroc 29 novembre – 4 décembre 1999 Point 8 de l’ordre du jour provisoire : Informations sur les listes indicatives et examen de propositions d’inscription de biens culturels et naturels sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril et la Liste du patrimoine mondial RESUME 1. A sa dix-septième session à Carthagène, en décembre 1993, le Comité a exprimé sa préoccupation quant au petit nombre de listes indicatives qui répondaient aux exigences stipulées aux paragraphes 7 et 8 des Orientations, et il a confirmé l'importance de ces listes pour la planification, l'analyse comparative des propositions d'inscription et la réalisation des études globales et thématiques. Ces listes constituent en outre un inventaire des biens situés sur le territoire de chaque Etat partie que ce dernier considère comme susceptibles d'être inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. Le Comité a également confirmé que les listes indicatives sont obligatoires pour les biens culturels pour lesquels les Etats parties ont l'intention de soumettre des propositions d'inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial dans les cinq à dix prochaines années. 2. En conséquence, le Comité a invité les Etats parties qui ne l'avaient pas encore fait, à soumettre leurs listes indicatives conformément aux Orientations, étant entendu qu’ "une assistance préparatoire sera fournie si nécessaire et à la demande de l'Etat partie concerné". -

De Groote Potloot

De Groote Potloot Oranjeschool, Mercer Island, USA, groep 7 en 8 Thema: Nederlandse Werelderfgoeden. Vol 10. Januari 2018 De Waddenzee Advertentie Door Joris Hutchison Als je bedreigde dieren wilt De Waddenzee is een wereld erfgoed, beschermen, doneer aan het net als de Chinese muur en de toren Wereld Natuur Fonds (WNF) van Pisa. Ze zijn officieel bekend door UNESCO. UNESCO is een onderdeel van de verenigde naties. Het is een De website: groote zee dat twee keer per dag leeg https://www.wnf.nl/ komt te liggen. Daar zijn ongeveer 40,000 zeehonden die leven in de Waddenzee. Word een WNF Ranger. De website: Daar zijn ook veel mosselen. De mosselen zijn eten voor mensen, https://www.wnf.nl/doe- vogels en krabben. In de bodem van mee/jeugdclubs/geef-een- de Waddenzee daar leven kleine wormen, krabben, en meer. Miljoenen wnf-ranger-op.htm trekvogels komen om al die wormen en krabben op te eten. De Waddenzee is een voedselplaats voor vogels en mensen, een huis voor krabben, schelpdieren, zeehonden en meer. Dankje wel voor mijn artikel te lezen! Foto bronnen: https://villanieuwland.nl/omgeving/zeehonden-bekijken-op-het-wad , https://erfgoedstem.nl/eerste -experiment-waddenzee-mosselen-als-wrakbescherming/ Bezoek deze site voor alle Nederlandse dingen in en om Seattle. http://www.dutchseattle.com/ _____________________________________________________________________________ De Groote Potloot, Januari 2018 Pagina 1 De Waddenzee Van Nelle Fabriek Door Anisa Dopps Door Miep Bar Clingan De Waddenzee is uniek in De Van Nelle Fabriek was gebouwd tussen de de wereld. Het is een van jaren 1925-1931. Het was gebouwd aan de rivier de wereld erfgoeden. -

Bakemavolume328lowres29 0.Pdf

OPEN:ABAKEMA CELEBRATION CONFRONTATION INTERPRETATION INVOCATION1: CIRCULATION SITUATION INSTALLATION IMPROVISATION COMPLICATION RECREATION INFORMATION DEMONSTRATION PROVOCATION RELATION INTERRELATION 2:OPEN Open the future direction of Dutch society, but together with the Guus Beumer and Dirk van den Heuvel office of Van den Broek en Bakema he also exemplified a practice that integrates design and research. Then and now, such integration seems necessary to achieve the innovation When Het Nieuwe Instituut was established as a needed in times of change. At the same time Bakema’s transdisciplinary merger between three separate institutes correspondence archive, especially the so-called ‘Post Box it also inherited the archive of the former Netherlands for the Development of the Habitat’, which Bakema initiated Architecture Institute, one of the largest collections of at the end of CIAM in 1959, is a wonderful and still inspiring architecture in the world. The question of how to open up example of the exchange of ideas between architects who this rich historical material had to be newly addressed. sought to contribute to the ideal of open and inclusive The specificity of the archive and its hundreds societies. Therefore, next to the installation proper and this of thousands of drawings, sketches, models, building paper publication, a contemporary post box will go online documents, photographs, and letters requires the during the Venice Biennale: the ‘Post Box for the Open development of an equally specific research program, in Society’, which will be open for anyone to participate in terms of scholarly qualities as well as artistic practices. debates and to contribute designs to counter the problems Thanks to the collaboration with TU Delft and the decision of societies today. -

The Fagus Factory in Alfeld

THE FAGUS FACTORY IN ALFELD NOMINATION FOR INSCRIPTION ON THE UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE LIST SEPTEMBER 2009 Summary SUMMARY I Fagus Factory – Nomination for Inscription on the Unesco World Heritage List II Summary State party Federal Republic of Germany State, province or region Lower Saxony, town of Alfeld Name of property Fagus factory Geographical coordinates to the nearest 51° 59’ 01” degrees North second 09° 48’ 40” degrees East Textual description of the boundary(ies) of Historical industrial area to the west of the the nominated property core city of Alfeld: the nominated area borders the Hanover-Göttingen rail route in the northeast and the Hannoversche Straße in the southwest. A4 (or „letter“) size map of the nominated See end of summary property, showing boundaries and buffer zone (if present) Justification With the construction of the Fagus factory, Statement of outstanding universal value Gropius made a breakthrough to new, modern art that went hand in hand with the age of technology. The Fagus factory, with a radical break from the conventional design practice, represents for the first time a new expression of architecture, which develops space and form from function, takes into account the light, air and lucidity require- ments of its users and makes use of the new technical possibilities of construction with glass and steel in industrially pre-produced processing. Glass, which is actually an unsubstantial material,becomes a formative building material and mode of expression of architecture.The design concepts underlying this construction had a decisive influence on the development of twentieth century architecture not only in Germany and Europe, but around the globe. -

Los Van De Aarde Architectuur Van Moderne Beweging Ontsnapt Aan Materie

LOS VAN DE AARDE ARCHITECTUUR VAN MODERNE BEWEGING ONTSNAPT AAN MATERIE PETER TIMMERMAN Hoog in de koepel van een barokkerk lost het materiaal waar het gebouw van gemaakt is op in licht of in een trompe- l’oeilschildering. De architecten probeerden hiermee het rijk van God uit te drukken: de immateriële hemel, verheven boven de aardse realiteit. In de moderne bouwkunst, aan het begin van de twintigste eeuw, zien we ook diverse pogingen om aan de materialiteit van het gebouw te ontsnappen. Gebouwen verliezen hun zwaarte en lijken door de toepassing van ijle constructies en veel glas te zweven in de ruimte, alsof ze van licht en lucht gemaakt zijn. n zijn klassiek geworden boek Space, Time and Architecture voerd, zoals bijvoorbeeld te zien is aan de luifels rond de centrale I(1941) beschrijft Sigfried Giedion het Bauhaus (Dessau, 1925) eetzaal. De dragende constructie loopt naar de randen toe af, omdat van Walter Gropius: ‘De immense glaswanden die de hoeken van daar minder gedragen hoeft te worden. Ook in dit gebouw bestaan het gebouw dematerialiseren zorgen ervoor dat de vloeren lijken te de hoeken geheel uit glas en lopen er lange vensters over de gevels, zweven.’ In de literatuur over waardoor verdiepingen boven moderne architectuur duikt re- elkaar lijken te zweven. Histori- gelmatig het begrip ‘immate- cus Giovanni Fanelli omschrijft rieel’ op of de term ‘ontmateria- Zonnestraal als een ‘gewichtloze liseren’. Voorts bestaan er tal- architectuur gemaakt van licht’. rijke beschouwingen over ge- Een soortgelijke omschrijving bouwen die hun ‘zwaarte verlie- vinden we bij architect Henk zen’ of die ‘zweven’.