Missions and Modern History Missions and Modern History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cole Collection

THE COLE COLLECTION If you would like more information on the collection or would like to access one of the documents, please send an email to [email protected] with the accompanying file number. A Zoryan Institute representative will get back to you within 48 hours. _________________________________________________________ THE COLE COLLECTION Journals, Letters, Lectures, Documents, Photographs, and Artifacts of Royal M. Cole and Lizzie C. Cole American Missionaries in Armenian and Kurdistan Turkey in the years 1868-1908 (c) 1996, M. Malicoat --------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS --------------- I. Royal Cole's journals: (a) Bound copy-book journals . p. 1 (b) Three smaller journals: 1. ‘Erzeroom Journal: War Times, 1877 - 1878’ . p. 7 2. ‘Travel Reminiscences’ . p. 7 3. Royal Cole’s personal diary of 1896: events at Bitlis, Van, and Moush; the Knapp affair: the persecution of American missionaries; relief work for Garjgan refugees . p. 7 II. Royal Cole’s copy-book journals: loose sheets: (a) Handwritten . p. 8 (b) Typed . p. 12 III. Drafts and notes for two projected volumes by Rev. Cole: (a) Dr. Cole’s Memoirs: ‘Interior Turkey Reminiscences, Forty Years in Kourdistan (Armenia)’ . p. 14 (b) ‘The Siege of Erzroom’; miscellaneous notes on The Russo-Turkish War . p. 15 IV. Newspaper articles by Royal Cole; miscellaneous newspaper articles on the subject of Armenian Turkey, in English, by various writers . p. 16 V. Lectures, essays, and letters by Mrs. Cole (Lizzie Cobleigh Cole) (a) Lectures . p. 17 (b) Copy-book journal loose-sheet essays and copy-book journal entries . p. 19 (c) Letters . p. 20 VI. Massacres in the Bitlis and Van provinces, 1894 - 1896: Sasun; Ghelieguzan; Moush; Garjgan sancak: charts, lists, maps . -

Talaat Pasha's Report on the Armenian Genocide.Fm

Gomidas Institute Studies Series TALAAT PASHA’S REPORT ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Ara Sarafian Gomidas Institute London This work originally appeared as Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1917. It has been revised with some changes, including a new title. Published by Taderon Press by arrangement with the Gomidas Institute. © 2011 Ara Sarafian. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-903656-66-2 Gomidas Institute 42 Blythe Rd. London W14 0HA United Kingdom Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction by Ara Sarafian 5 Map 18 TALAAT PASHA’S 1917 REPORT Opening Summary Page: Data and Calculations 20 WESTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 22 Constantinople 23 Edirne vilayet 24 Chatalja mutasarriflik 25 Izmit mutasarriflik 26 Hudavendigar (Bursa) vilayet 27 Karesi mutasarriflik 28 Kala-i Sultaniye (Chanakkale) mutasarriflik 29 Eskishehir vilayet 30 Aydin vilayet 31 Kutahya mutasarriflik 32 Afyon Karahisar mutasarriflik 33 Konia vilayet 34 Menteshe mutasarriflik 35 Teke (Antalya) mutasarriflik 36 CENTRAL PROVINCES (MAP) 37 Ankara (Angora) vilayet 38 Bolu mutasarriflik 39 Kastamonu vilayet 40 Janik (Samsun) mutasarriflik 41 Nigde mutasarriflik 42 Kayseri mutasarriflik 43 Adana vilayet 44 Ichil mutasarriflik 45 EASTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 46 Sivas vilayet 47 Erzerum vilayet 48 Bitlis vilayet 49 4 Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide Van vilayet 50 Trebizond vilayet 51 Mamuretulaziz (Elazig) vilayet 52 SOUTH EASTERN PROVINCES AND RESETTLEMENT ZONE (MAP) 53 Marash mutasarriflik 54 Aleppo (Halep) vilayet 55 Urfa mutasarriflik 56 Diyarbekir vilayet -

Woodrow Wilson Boundary Between Turkey and Armenia

WOODROW WILSON BOUNDARY BETWEEN TURKEY AND ARMENIA The publication of this book is sponsored by HYKSOS Foundation for the memory of General ANDRANIK – hero of the ARMENIAN NATION. Arbitral Award of the President of the United States of America Woodrow Wilson Full Report of the Committee upon the Arbitration of the Boundary between Turkey and Armenia. Washington, November 22nd, 1920. Prepared with an introduction by Ara Papian. Includes indices. Technical editor: Davit O. Abrahamyan ISBN 978-9939-50-160-4 Printed by “Asoghik” Publishing House Published in Armenia www.wilsonforarmenia.org © Ara Papian, 2011. All rights reserved. This book is dedicated to all who support Armenia in their daily lives, wherever they may live, with the hope that the information contained in this book will be of great use and value in advocating Armenia’s cause. Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924) 28th President of the United States of America (March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921) ARBITRAL AWARD OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WOODROW WILSON FULL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE UPON THE ARBITRATION OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN TURKEY AND ARMENIA WASHINGTON, NOVEMBER 22ND, 1920 PREPARED with an introduction by ARA PAPIAN Yerevan – 2011 Y Z There was a time when every American schoolboy knew of Armenia, the entire proceeds of the Yale-Harvard Game (1916) were donated to the relief of “the starving Armenians,” and President Woodrow Wilson’s arbitration to determine the border between Armenia and Ottoman Turkey was seen as natural, given the high standing the 28th President enjoyed in the Old World. -

The World War and the Turco-Armenian Question

THE WORLD WAR AND THE TURCO-ARMENIAN QUESTION BY AHMED RUSTEM BEY Formerly Turkish Ambassador in Washington Berne 1918 translated by Stephen Cambron PERSONAL EXPLANATION OF THE AUTHOR The son of a Pole, who having been harbored in Turkey after the Hungarian abortive Revolution of 1848, served this country as an officer and was the object of government favors till his death, I was infeoffed to the Turkish people as much out of thankfulness as because of their numerous, amiable qualities. In writing this book intended to defend turkey against the Western public opinion concerning the Turco-Armenian question, I have only given way to my grateful feelings towards the country where I was born and which made me, in my turn, the object of her benevolence. These feelings expressed themselves by acts of indubitable loyalty and there is they reason why I fought twice in duel to maintain her honor and served her as a volunteer during the Turco-Greek War. It is after having ended my career and assured a long time ago of the kind feelings of the Ottoman Government and of my Turkish fellowmen’s that I publish this work under my name. Thereby I mean to say that I am only obeying my love towards the country. As to the degree of conviction with which I put my pen to her service in this discussion, where the question is to prove that Turkey is not so guilty as report goes and in which passions are roused to the utmost is sufficiently fixed by my signing this defense in which I speak the plain truth to the Armenian committees and the Entente. -

Fables Which L•Re- Ent a Summary of the Finance and Commerce of the Unit

INDEX THIS Index contains no reference to the Introductory 'fables which l•re• ent a summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United Kingdom, British India., the British Colanies, the various countries of Europe, the United States of America, and Japan, and various other matters, as well as Additions and Con-ections ; nor will reference to such topics as Gold, Wheat, &c., be found otherwise than under the producing countries. AAC AFG ACHEN (Prussia), 829 Achaia, 920 A Aalborg (Denmark), 725 Achole (Uganda), 174 Au.len (Wurtemberg}, 915 Acklin's Island (Baha.mas), 264 Aalesund (Norwu.y), 1064 Aconcagua (Chili), 676 Aargu.u (cu.nton), 1249, 1251 Acre Ter. (Brazil), 659 Aarhus (Denmu.rk), 725 Adana (vilayet), 1266, 1275 Abaca Islu.nd (Baham&l!}, 264 Adelaide, 281, 312 ; University, Abu.ngarez mines (Costa Rica), 714 313 Abbas Hilmi, Khedive, 1287 Aden, 99. 119 ; boundary, 99, 12 Abeokuta (W. Africa), 230 Adis Ababa, 563 Abercorn (Rhodesia), 192 Adjame (Ivory Coast), 807 Aberdeen, 19; University, 28, 29 Admiralty Island (W. Pacific), 863 Aberystwith College, 29 Adolf Friedrich (Grand-duke, Meck- Abeshr (Wadai), 797 lenburg-Strelitz), 888 Abo (Finlu.nd), 1163, 1164, 1186 Adrar (Spanish Sahara), 1229 Abomey, 808 Adriu.nople (town), 1267 Abrnzzi e M.olise, 946 - (vilayet), 1266 Abuua. (Coptic), 664 Adua (Abyssinia), 564 Abyssinia, area, 663 lEgean Islands, 924 -army, 663 Afghanistan, area, 567, 568 - books of reference, 666-6 : - army, 568-9 - commerce, 664-6 - books of reference, 570 - education, 664 - commerce, 569-70 -gold, 564 - currency, -

Centralization and Localism : Some Aspects of Ottoman Policy In

CENTRALIZATION AND LOCALISPI ASPECTS OF OTTOMAN POLICY IN EASTERN AN ATOLIA 1878-1908 Stephen Ralph Duguid B.A. University of Illinois, 1966 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PMTIAL FULFILLRENT OF ThE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF NASTER OF A8TS in the Department @ STEPHEN RALPH DUGUID 1970 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY APRIL, 1970 Allan Cunninghas - Senior Supervisor ~dilliamC tovoland f xamining Committee A.H. SO@&@ Examining Committern . am.: Stephen Ralph Duquid . eqree~ maater of Arts I It'~kitld of Thesist CmtraliZation and L @Bar Aspects of Ottoman e; a Policy in Eastern A ia 1078-1908 *. iii ABSTRACT The primary rationale behind this thesis is that the greatest need in the study of the Ottoman Empire is for detailed analyses of specific areas and aspects of that Empire, The trend of latm in Ottoman historiography is a general testing of generalizations made in the past about the Empire in the light of more thorough research and, indeed, a calling into question of whether any generalization about such a multi-national, multi-religious, and complicated state is practicable or possible, Both the area and the period of this study were chosen bacause of the lack of interest shown in them by most other historians and because they contain examples of many of the crucial problems faced by the Ottomans in the nineteenth century, One must avoid the conclusion, hewever, that eastern Anatolia is meant to be a model for Ottoman policy in other parts of the Empire where the problems, the local forces, and the policy were in many cases quite different. The thesis is primarily concerned with examining the political and social groups, both traditional and 'modernf, within eastern I Anatolia; the relationships between these groups (such as nomads ;I I I - -- - - .- -- -- -- I I and villagers, Muslims and Armenians, notables and Kurds, and so --- .-- - -.---- -. -

Peasants, Pastoralists, and Climate Crises in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1840-1890

BEYOND “THE DESERT AND THE SOWN”: PEASANTS, PASTORALISTS, AND CLIMATE CRISES IN OTTOMAN DIYARBEKIR, 1840-1890 by Zozan Pehlivan A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada February, 2016 Copyright ©Zozan Pehlivan, 2016 Abstract This dissertation refocuses attention from a ‘clash of cultures’ to a ‘clash of environmental economies’ within the eastern regions of the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire, particularly the province of Diyarbekir. An account of changing patterns of climate provides an alternative vantage point on the origins of inter-social relationships within this region. In the aftermath of intermittent climate-induced environmental crises, peasants and pastoralists confronted different challenges. Overall, crop-based economies could recover more quickly than herding-based economies. Given enough water and seed, and normal weather conditions, farmers could replant and expect good harvests the following season. However, pastoralists, who either lost or sold most of their animals as a result of lack of food and water needed many seasons of abundant grass and water to rebuild their herds to their former size. Examining episodes of severe climate in the Ottoman east in the 1840s and 1880s, this study presents evidence that the different timetables for recovery following episodes of environmental crisis were consequential for understanding changing relationships between people, land, and animals as well as relations between communities. ii Acknowledgements The history of this dissertation began on a September morning in 2011 in the Asian and African Studies Reading Room, located on the third floor of the British Library. -

Turco-Armenian

THE TURCO-ARMENIAN QUESTION THE TURKISH POINT OF VIEW PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL CONGRESS OF TURKEY CONSTANTINOPLE Societe Anonyme de Papeterie et d’Limprimerie 1919 Serie B. – No 1. THE TURCO-ARMENIAN QUESTION TREATMENT Of the non Moslem in General in the Ottoman Empire Though sorely embarrassed in her relations with her Christian subjects whose loyalty was never above doubt, Turkey sincerely strove for close upon a century to ensure to the non-Moslem elements under her sway equal treatment and rights with those of the Musulmans. This idea pervades the whole legislation enacted in the Empire since the “TANZIMAT” (era of reforms inaugurated by the proclamation of the Charter of Gulhane in 1839) and was in great part realized when Russia, herself more than ever attached to a system of Government by which her non-Orthodox subjects were condemned to a marked state of inferiority in regard to their compatriots professing the state-religion, declared war upon her neighbor in 1876 under the pretext of obtaining its application. If this work had not been carried out entirely until then, the reason of it is to be found in the fact that the disappearance of Musulman supremacy would have given rise to perpetual conflicts between the different Christian sects whose hatred for one another knew no bounds.(I) This is how the French diplomatist and historian M. Engelhardt expresses himself on the subject in his book “Turkey and the Tanzimat” “. .But in advocating the advantages of a common regime, the Divan was averse to complete assimilation which would have compromised Musulman supremacy, in its opinion the only barrier against anarchy. -

British Representations of the Kurds and the Armenian Question 1878

British Representations of the Kurds and the Armenian Question 1878-1908 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Adnan Amin Mohammed School of History, Politics & International Relations University of Leicester 2018 Abstract There are still gaps in the understanding of British representations of the Armenian question which was an important issue for Britain for decades. Notably, the Kurds were one of the most influential parties in the Armenian question and had a significant impact upon it. However, to date, there has been no study about how the British, who were the Europeans closest to the Armenian question, regarded the Kurds and their position in this conflict. It is this issue, therefore, that this thesis addresses. The thesis investigates the British perceptions of the Kurdish position and contributes to a better understanding of the image of the Kurds in the late Victorian period. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Kurds were seen in Britain through the prism of the Armenian question and were generally presented as oppressors of the Christians. This thesis examines the British views, official and public, of the Kurds and shows the effects of these perceptions in shaping British attitudes towards the Kurds, which in turn influenced British policy towards the Ottoman Empire. The study highlights the growing British attention to the Kurds as part of wider British concerns relating to the Armenian question and eastern Anatolia, which was an essential area for British interests in the East. This thesis is based upon analysis of British primary sources that have not previously been systematically analysed in relation to the history of the Kurds and their relations with the Armenians. -

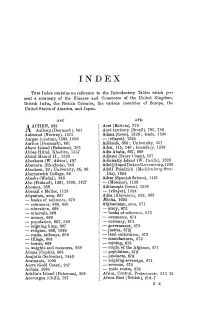

Tms Index Contains No Reference to the Introductory Tables Which Pre- Sent a Summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United K

INDEX Tms Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables which pre sent a summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United Kingdom, British I nrlia, the British Colonies, the various countries of Europe, the United States of America, and Japan. AAC AFR ACHEN, 982 Acre (Bolivia), 778 A Aalborg (Denmark), 861 Acre territory (Brazil), 785, 786 Aalesund (Norway), 1275 Adana (town), 1526 ; trade, 1536 Aargau (canton), 1503, 1506 - (vilayet), 1525 Aarhus (Denmark), 861 Adelttide, 356; University, 357 Abaca Island (Bahamas), 305 Aden, 115, 140; boundary, 1530 Abbas Hilmi, Khedive, 1557 Adis Ababa, 667, 668 Abdul-Hamid II., 1520 Adjame (Ivory Coast), 957 Abeokuta (W. Africa), 487 Admiralty Island (W. Pacific), 1023 Abercorn (Rhodesia), 245 Adolf, Grand DnkeofLnxembnrg,1200 Aberdeen, 2il; University, 35, 36 Adolf Friedrich (Mecklen bnrg.Stre· Aberystwith College, 36 litz), 1054 Abeshr (Wadai), 945 Adrar (Spanish Sahara), 1481 Abo (Finland), 1381, 1399, 1427 -(Morocco), 1159. Abomey, 958 Adrianople (town), 1526 Abrnzzi e Molise, 1128 - (vilayet), 1524 Abyssinia, area, 667 Adua (Abyssinia), 624, 668 - books of reference, 670 lEtolia, 1095 - commerce, 668, 669 Afghanistan, area, 671 - education, 668 -army, 672 - minerals, 668 -books of reference, 673 -money, 669 -commerce, 674 - population, 667, 668 -currency, 674 - reigning king, 667 - government, 672 - religion, 668, 1562 -justice, 672j - roads, railways, 669 -land cultivation, 6/3 - tillage, 668 -manufactures, 673 -towns, 668 - mining, 673 - weights and measures, 669 - origin o~ the -

Some Notes on the Settlement of Northern Caucasians in Eastern

Some Notes on the Settlement of Northern Caucasians in Eastern Anatolia and Their Adaptation Problems (the Second Half of the XIXth Century - the Beginning of the XXth Century) Georgi Chochiev* Bekir Koç** Journal of Asian History, 40/1 (2006), pp. 80-103. I-Socio-Political Situation of Eastern Anatolia during the Process of the Settlement of Northern Caucasian Refugees Although the migration of Northern Caucasian refugees (or Circassians in their common name1) to Eastern Anatolia2 was reflective of the settlement policy of the Ottoman Empire, it also had certain particularities stemming from the demographic and socio-economic structure of the eastern provinces. Hence, one of the most significant characteristics of Eastern Anatolia was the high ethno-religious heterogeneity of the population that was around 2,5 million in the second half of the XIXth century. The population of the region in question comprised of Turks, who had significant lead in the northern and western parts of the region; Kurds, who were mostly divided into tribal and local factions; Armenians, who had no pre-eminence with a few exceptions; and Assyrians and Arabs concentrated in the south.3 Another characteristic that had marked every aspect of condition of Eastern Anatolia was the lack of control by the central administration. The areas under control were mainly restricted to cities, villages close to these cities, and some contiguous with Russia and Iran areas where regular troops were kept. As for the greater part of Eastern * North Ossetian State University (Russia), Faculty of International Relations, Department of Turcology. ** Ankara University, Faculty of Letters, Department of History. -

The Politics of Clothing in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1890-1910

MELİKE BATGIRAY OF DISGUISE AND PROVOCATION: THE POLITICS OF CLOTHING IN THE LATE OTTOMAN EMPIRE, 1890-1910 A Master's Thesis OF DISGUISE by MELİKE BATGIRAY AND PROVOCATION Department of History İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara August 2019 Bilkent University 2019 “For Everyone and Nobody” - Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra OF DISGUISE AND PROVOCATION: THE POLITICS OF CLOTHING IN THE LATE OTTOMAN EMPIRE, 1890-1910 The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by MELİKE BATGIRAY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA August 2019 ABSTRACT OF DISGUISE AND PROVOCATION: THE POLITICS OF CLOTHING IN THE LATE OTTOMAN EMPIRE, 1890-1910 Batgıray, Melike M.A, Department of History Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Evgeniy Radoslavov Radushev August 2019 This thesis aims to analyze the fedayee practice of disguise in the context of violence between the years of 1890 and 1910 in the North-east parts of the Ottoman Empire. It mainly focuses on the practice’s itself and reason behind it. Making use of photographs, this thesis also examines the politics of clothing and self-representation. At this juncture, objects in photographs which were intentionally placed fallacious and delusive are examined to clarify possible fedayee clothes which are also analyzed. In order to make sense of the penchant of Armenian fedayees for disguise, this thesis also explores the complexity of Kurdish, Circassian, Georgian, Laz clothing through photographic evidence. Keywords: Disguise, Fedayee, Paramilitary ethnic groups, Photography, the Ottoman Empire iii ÖZET KILIK DEĞİŞTİRME VE PROVOKASYON: GEÇ DÖNEM OSMANLI İMPARATORLUĞUNDA KIYAFET POLİTİKALARI, 1890-1910 Batgıray, Melike Yüksek Lisans, Tarih Bölümü Tez Danışmanı: Dr.