British Representations of the Kurds and the Armenian Question 1878

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cole Collection

THE COLE COLLECTION If you would like more information on the collection or would like to access one of the documents, please send an email to [email protected] with the accompanying file number. A Zoryan Institute representative will get back to you within 48 hours. _________________________________________________________ THE COLE COLLECTION Journals, Letters, Lectures, Documents, Photographs, and Artifacts of Royal M. Cole and Lizzie C. Cole American Missionaries in Armenian and Kurdistan Turkey in the years 1868-1908 (c) 1996, M. Malicoat --------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS --------------- I. Royal Cole's journals: (a) Bound copy-book journals . p. 1 (b) Three smaller journals: 1. ‘Erzeroom Journal: War Times, 1877 - 1878’ . p. 7 2. ‘Travel Reminiscences’ . p. 7 3. Royal Cole’s personal diary of 1896: events at Bitlis, Van, and Moush; the Knapp affair: the persecution of American missionaries; relief work for Garjgan refugees . p. 7 II. Royal Cole’s copy-book journals: loose sheets: (a) Handwritten . p. 8 (b) Typed . p. 12 III. Drafts and notes for two projected volumes by Rev. Cole: (a) Dr. Cole’s Memoirs: ‘Interior Turkey Reminiscences, Forty Years in Kourdistan (Armenia)’ . p. 14 (b) ‘The Siege of Erzroom’; miscellaneous notes on The Russo-Turkish War . p. 15 IV. Newspaper articles by Royal Cole; miscellaneous newspaper articles on the subject of Armenian Turkey, in English, by various writers . p. 16 V. Lectures, essays, and letters by Mrs. Cole (Lizzie Cobleigh Cole) (a) Lectures . p. 17 (b) Copy-book journal loose-sheet essays and copy-book journal entries . p. 19 (c) Letters . p. 20 VI. Massacres in the Bitlis and Van provinces, 1894 - 1896: Sasun; Ghelieguzan; Moush; Garjgan sancak: charts, lists, maps . -

Talaat Pasha's Report on the Armenian Genocide.Fm

Gomidas Institute Studies Series TALAAT PASHA’S REPORT ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Ara Sarafian Gomidas Institute London This work originally appeared as Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1917. It has been revised with some changes, including a new title. Published by Taderon Press by arrangement with the Gomidas Institute. © 2011 Ara Sarafian. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-903656-66-2 Gomidas Institute 42 Blythe Rd. London W14 0HA United Kingdom Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction by Ara Sarafian 5 Map 18 TALAAT PASHA’S 1917 REPORT Opening Summary Page: Data and Calculations 20 WESTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 22 Constantinople 23 Edirne vilayet 24 Chatalja mutasarriflik 25 Izmit mutasarriflik 26 Hudavendigar (Bursa) vilayet 27 Karesi mutasarriflik 28 Kala-i Sultaniye (Chanakkale) mutasarriflik 29 Eskishehir vilayet 30 Aydin vilayet 31 Kutahya mutasarriflik 32 Afyon Karahisar mutasarriflik 33 Konia vilayet 34 Menteshe mutasarriflik 35 Teke (Antalya) mutasarriflik 36 CENTRAL PROVINCES (MAP) 37 Ankara (Angora) vilayet 38 Bolu mutasarriflik 39 Kastamonu vilayet 40 Janik (Samsun) mutasarriflik 41 Nigde mutasarriflik 42 Kayseri mutasarriflik 43 Adana vilayet 44 Ichil mutasarriflik 45 EASTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 46 Sivas vilayet 47 Erzerum vilayet 48 Bitlis vilayet 49 4 Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide Van vilayet 50 Trebizond vilayet 51 Mamuretulaziz (Elazig) vilayet 52 SOUTH EASTERN PROVINCES AND RESETTLEMENT ZONE (MAP) 53 Marash mutasarriflik 54 Aleppo (Halep) vilayet 55 Urfa mutasarriflik 56 Diyarbekir vilayet -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Tanzimat'a Giden Yolda Bir Osmanlı Kenti Sivas

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı TANZİMAT’A GİDEN YOLDA BİR OSMANLI KENTİ: SİVAS (1777-1839) Serpil SÖNMEZ Doktora Tezi Ankara, 2015 TANZİMAT’A GİDEN YOLDA BİR OSMANLI KENTİ: SİVAS (1777-1839) Serpil SÖNMEZ Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı Doktora Tezi Ankara, 2015 iii ÖZET Sönmez, Serpil. Tanzimat’a Giden Yolda Bir Osmanlı Kenti: Sivas (1777-1839), Doktora Tezi, Ankara, 2015. 1777-1839 yılları arasında Sivas Şehri’ni idarî ve toplamsal yapısını inceleyen bu çalışma üç ana bölümden oluşmaktadır. Birinci bölüm daha ziyade konuya giriş mahiyetinde olduğundan Sivas Şehri’nin içinde yer aldığı bölgeyi kısaca tarif etmeyi hedeflemektedir. Bu amaçla bu bölümde Tanzimat öncesinde Osmanlı taşra teşkilatının nasıl oluştuğu, Sivas Eyaleti’nin idarî yapısı ve 18.yüzyılın son çeyreğinden Tanzimat öncesine kadar eyaleti etkileyen eşkıyalık, savaş vb. olaylar kısaca incelenmiştir. Böylece Sivas Şehri’nin bulunduğu coğrafyanın durumu tarif edilmeye çalışılmıştır. Çalışmanın belkemiğini oluşturan asıl bölümler Yönetim başlıklı ikinci ve Şehir başlıklı üçüncü bölümlerdir. Yönetim ana başlığı altında Tanzimat öncesinde Sivas Şehri’nin yöneticileri ve yönetim mekanizmasının nasıl işlediği incelenmiştir. Bu bölümde vali ve vali vekili olarak mütesellim, kadı, müftü, nakîbüleşraf kaymakamı, bedesten kethüdası, şehir kethüdası, muhtesip, pazarbaşı, imam, keşiş ve muhtar gibi belli başlı yöneticilerin göreve geliş prosedürleri, bunların görev ve sorumlulukları, merkez-taşra ilişkisinde nasıl bir rolleri olduğu gibi konular incelenirken, bu makamlara bağlı olarak çalışan diğer görevliler de yeri geldikçe ele alınmıştır. Yöneticilerin gelir ve giderleri de ayrı bir başlık altında incelenmiştir. Ayrıca salyane defteri hazırlanması, mubayaa, asker toplanması ve sevk edilmesi ve çeşitli vergilerin toplanması gibi görevlerin hangi yöneticiler tarafından nasıl yapıldığı incelenerek yöneticilerin işlerin yürütülmesindeki rollerinin ortaya çıkarılması amaçlanmıştır. -

2017 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FALL 2017 Liminality & ISSUE 11 Memorial Practices IN 3 Notes from the Director THIS 4 Faculty News and Updates ISSUE: 6 Year in Review: Orphaned Fields: Picturing Armenian Landscapes Photography and Armenian Studies Orphans of the Armenian Genocide Eighth Annual International Graduate Student Workshop 11 Meet the Manoogian Fellows NOTES FROM 14 Literature and Liminality: Exploring the Armenian in-Between THE DIRECTOR Armenian Music, Memorial Practices and the Global in the 21st 14 Kathryn Babayan Century Welcome to the new academic year! 15 International Justice for Atrocity Crimes - Worth the Cost? Over the last decade, the Armenian represents the first time the Armenian ASP Faculty Armenian Childhood(s): Histories and Theories of Childhood and Youth Studies Program at U-M has fostered a Studies Program has presented these 16 Hakem Al-Rustom in American Studies critical dialogue with emerging scholars critical discussions in a monograph. around the globe through various Alex Manoogian Professor of Modern workshops, conferences, lectures, and This year we continue in the spirit of 16 Multidisciplinary Workshop for Armenian Studies Armenian History fellowships. Together with our faculty, engagement with neglected directions graduate students, visiting fellows, and in the field of Armenian Studies. Our Profiles and Reflections Kathryn Babayan 17 postdocs we have combined our efforts two Manoogian Post-doctoral fellows, ASP Fellowship Recipients Director, Armenian to push scholarship in Armenian Studies Maral Aktokmakyan and Christopher Studies Program; 2017-18 ASP Graduate Students in new directions. Our interventions in Sheklian, work in the fields of literature Associate Professor of the study of Armenian history, literature, and anthropology respectively. -

Woodrow Wilson Boundary Between Turkey and Armenia

WOODROW WILSON BOUNDARY BETWEEN TURKEY AND ARMENIA The publication of this book is sponsored by HYKSOS Foundation for the memory of General ANDRANIK – hero of the ARMENIAN NATION. Arbitral Award of the President of the United States of America Woodrow Wilson Full Report of the Committee upon the Arbitration of the Boundary between Turkey and Armenia. Washington, November 22nd, 1920. Prepared with an introduction by Ara Papian. Includes indices. Technical editor: Davit O. Abrahamyan ISBN 978-9939-50-160-4 Printed by “Asoghik” Publishing House Published in Armenia www.wilsonforarmenia.org © Ara Papian, 2011. All rights reserved. This book is dedicated to all who support Armenia in their daily lives, wherever they may live, with the hope that the information contained in this book will be of great use and value in advocating Armenia’s cause. Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924) 28th President of the United States of America (March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921) ARBITRAL AWARD OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WOODROW WILSON FULL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE UPON THE ARBITRATION OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN TURKEY AND ARMENIA WASHINGTON, NOVEMBER 22ND, 1920 PREPARED with an introduction by ARA PAPIAN Yerevan – 2011 Y Z There was a time when every American schoolboy knew of Armenia, the entire proceeds of the Yale-Harvard Game (1916) were donated to the relief of “the starving Armenians,” and President Woodrow Wilson’s arbitration to determine the border between Armenia and Ottoman Turkey was seen as natural, given the high standing the 28th President enjoyed in the Old World. -

Under Crescent and Star

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^^H m ' '- PI; H ; I UNDER CRESCENT AND STAR BY LIEUT. -COL. ANDKEW HAGGAKD, D.S.O. ' AUTHOR OF 'DODO AND I," TEMPEST -TORN,' ETC. WITH PORTRAIT WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCXCV DT 107.3 TO ALL MY OLD COMRADES WHO FOUGHT OR DIED IN EGYPT. ANDREW HAGGARD. NAVAL AND MILITARY CLUB, November 1895. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE " Learning Arabic The 1st Reserve Depot Devils in hell "- " " " Too late for the battle We don't want to work The dear old false prophet" The mosquitos' revenge on the musketeers . 1 CHAPTER II. Cairo The domestic ass Security in the city The Khedive on Tommy Atkins Bedaween on the road Parapets and pyramids Alexandria . .14 CHAPTER III. Old Egyptian army worthless How disposed of under Hicks Pasha and Valentine Baker Baker's disappointment Sir Evelyn Wood to command Constitution of the new Egyp- tian army Officers' contracts Coetlogou The Duke of Sutherland Medals and promotions Sugar-candy . 23 CHAPTER IV. Formation of the new army How officered Difficulties of lan- guage and drill The music question We conform to Ma- homedan customs Big dinners The Khedive's reception Lord Dufferin's pleasant ways . .39 Vlll CONTENTS. CHAPTER V. The Duke of Hamilton and Turner His kindness to the Shrop- shire Regiment The Khedive at Alexandria The officers visit him on accession day Ramadan begins Drilling at night We make cholera camps and cholera hospital Win- gate's good work Turner's pluck and peculiarities The epidemic awful in Cairo Death lists at dinner Devotion of . -

A College Studentâ•Žs Perspective On

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Social Work Theses Social Work Spring 2012 Caught in Cultural Limbo?: A College Student’s Perspective on Growing Up with Immigrant Parents Melissa Weiss Providence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/socialwrk_students Part of the Social Work Commons Weiss, Melissa, "Caught in Cultural Limbo?: A College Student’s Perspective on Growing Up with Immigrant Parents" (2012). Social Work Theses. 85. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/socialwrk_students/85 It is permitted to copy, distribute, display, and perform this work under the following conditions: (1) the original author(s) must be given proper attribution; (2) this work may not be used for commercial purposes; (3) users must make these conditions clearly known for any reuse or distribution of this work. Caught in Cultural Limbo?: A College Student’s Perspective on Growing Up with Immigrant Parents Melissa Weiss Providence College A project based upon an independent investigation, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Social Work. 2012 2 Abstract Much recent scholarship of immigrants, has found a second-generation disadvantage, or an “immigrant paradox” instead of a “second generation advantage”. In contrast to past studies, this study employed qualitative methods to explore mental health and risky behavior variables of the immigrant paradox among college-aged children of immigrants who attend a private, liberal arts institution to gain a more meaningful understanding of this “paradox”. No strong evidence suggesting an “immigrant paradox” in terms of these variables was found, but instead participants expressed cultural pride. It was also found that these individuals valued their present support systems and those they had while growing up. -

The World War and the Turco-Armenian Question

THE WORLD WAR AND THE TURCO-ARMENIAN QUESTION BY AHMED RUSTEM BEY Formerly Turkish Ambassador in Washington Berne 1918 translated by Stephen Cambron PERSONAL EXPLANATION OF THE AUTHOR The son of a Pole, who having been harbored in Turkey after the Hungarian abortive Revolution of 1848, served this country as an officer and was the object of government favors till his death, I was infeoffed to the Turkish people as much out of thankfulness as because of their numerous, amiable qualities. In writing this book intended to defend turkey against the Western public opinion concerning the Turco-Armenian question, I have only given way to my grateful feelings towards the country where I was born and which made me, in my turn, the object of her benevolence. These feelings expressed themselves by acts of indubitable loyalty and there is they reason why I fought twice in duel to maintain her honor and served her as a volunteer during the Turco-Greek War. It is after having ended my career and assured a long time ago of the kind feelings of the Ottoman Government and of my Turkish fellowmen’s that I publish this work under my name. Thereby I mean to say that I am only obeying my love towards the country. As to the degree of conviction with which I put my pen to her service in this discussion, where the question is to prove that Turkey is not so guilty as report goes and in which passions are roused to the utmost is sufficiently fixed by my signing this defense in which I speak the plain truth to the Armenian committees and the Entente. -

The Armenians

THE CASE FOR THE ARMENIANS _ WITH: AN INTRODUCTION FRANCIS SEYMOUR STEVENSON, M.P. (PrEsIDENT oF THE ANGLO-ARMENIAN AssOCIATION), And a Full Report of the Speeches delivered at the Banquet in honour of the Right Hon. James Brycr, M.P., D.C.L., on Friday, May 12th, 1893. LONDON: »PRINTED FOR THE ANGLO-ARMENIAN ASSOCIATION, 8, Prownzx E.C., axp PUBLISHED BY HARRISON AND SONS, 50, PALL MALL, S.W. Price Qne Shilling. coNTENTS. PAGE T.-Introduction .. +s « -+ Pe e +. TI.-An Appeal to the British Nation .. a 10 TIT.-Memorandum by Nubar Pasha e i+ 12 IV.-Mz, Gladstone, Mr, Bryce, Sir John Kennaway, and Sir James Fergusson on the Armenian Question as o 19 V.-The Duke of Argyll and the Bishop of Manchester on Turkish Misrule .+ o B o «: 22 VI--The Anglo-Armenian Association .. « a+ «+ 27 VII.-Mr. Gladstone on Consular Reports .. + +. + 31 VIIL-Circular Letter to Armenians in Europe and America «. ++ i% as 33 _.TX.-Banquet to Mr. Bryce e +x ANGLO-ARMENIAN ASSOCIATION. In consequence of the reiterated official statements recently made at Constantinople by the Grand Vizier and Said Pasha, alleging that the Anglo-Armenian Association is a revolutionary society, the committee has republished a formal declaration issued byit two years ago, stating in explicit terms that its members are solely desirous of securing the protection of Oriental Christians and the execution of the administrative and judicial reforms which, in 1878, the Sublime Porte undertook to carry out in the Armenian Provinces of Asiatic Turkey, and which expressly guaranteed by the 6lst Article of the Treaty of Ereerlin. -

Soldier, Structure and the Other

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto SOLDIER, STRUCTURE AND THE OTHER SOCIAL RELATIONS AND CULTURAL CATEGORISATION IN THE MEMOIRS OF FINNISH GUARDSMEN TAKING PART IN THE RUSSO- TURKISH WAR, 1877-1878 Teuvo Laitila Dissertation in Cultural Anthropology, University of Helsinki, Finland, 2001 1 ISSN 1458-3186 ISBN (nid.) 952-10-0104-6 ISBN (pdf) 952-10-105-4 Teuvo Laitila 2 ABSTRACT SOLDIER, STRUCTURE AND THE OTHER:SOCIAL RELATIONS AND CULTURAL CATEGORISATION IN THE MEMOIRS OF FINNISH GUARDSMEN TAKING PART IN THE RUSSO-TURKISH WAR, 1877-1878 Teuvo Laitila University of Helsinki, Finland I examine the influence of Finnish tradition (public memory) about the ’correct’ behaviour in war and relative to the other or not-us on the ways the Finnish guardsmen described their experiences in the Russo-Turkish war, 1877-1878. Further, I analyse how the men’s peacetime identity was transformed into a wartime military one due to their battle experiences and encounters with the other (the enemy, the Balkans and its civilian population) and how public memory both shaped this process and was reinterpreted during it. Methodologically I combine Victor Turner’s study of rituals as processes with Maurice Halbwachs’s sociologial insights about what he termed mémoire collective and what I have called public memory, and Eric Dardel’s geographical view about the meaning of space in remembering. My sources are the written recollections of the Finnish guardsmen, both volunteers and professionals. I have broken each recollection (nine together) down into themes (military ideals, views of the enemy, battle, the civilians or Bulgarians, etc.) and analysed them separately, letting every author tell his story about each thema. -

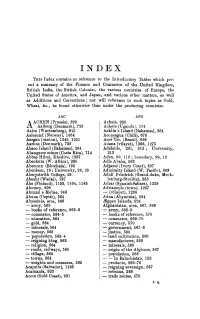

Fables Which L•Re- Ent a Summary of the Finance and Commerce of the Unit

INDEX THIS Index contains no reference to the Introductory 'fables which l•re• ent a summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United Kingdom, British India., the British Colanies, the various countries of Europe, the United States of America, and Japan, and various other matters, as well as Additions and Con-ections ; nor will reference to such topics as Gold, Wheat, &c., be found otherwise than under the producing countries. AAC AFG ACHEN (Prussia), 829 Achaia, 920 A Aalborg (Denmark), 725 Achole (Uganda), 174 Au.len (Wurtemberg}, 915 Acklin's Island (Baha.mas), 264 Aalesund (Norwu.y), 1064 Aconcagua (Chili), 676 Aargu.u (cu.nton), 1249, 1251 Acre Ter. (Brazil), 659 Aarhus (Denmu.rk), 725 Adana (vilayet), 1266, 1275 Abaca Islu.nd (Baham&l!}, 264 Adelaide, 281, 312 ; University, Abu.ngarez mines (Costa Rica), 714 313 Abbas Hilmi, Khedive, 1287 Aden, 99. 119 ; boundary, 99, 12 Abeokuta (W. Africa), 230 Adis Ababa, 563 Abercorn (Rhodesia), 192 Adjame (Ivory Coast), 807 Aberdeen, 19; University, 28, 29 Admiralty Island (W. Pacific), 863 Aberystwith College, 29 Adolf Friedrich (Grand-duke, Meck- Abeshr (Wadai), 797 lenburg-Strelitz), 888 Abo (Finlu.nd), 1163, 1164, 1186 Adrar (Spanish Sahara), 1229 Abomey, 808 Adriu.nople (town), 1267 Abrnzzi e M.olise, 946 - (vilayet), 1266 Abuua. (Coptic), 664 Adua (Abyssinia), 564 Abyssinia, area, 663 lEgean Islands, 924 -army, 663 Afghanistan, area, 567, 568 - books of reference, 666-6 : - army, 568-9 - commerce, 664-6 - books of reference, 570 - education, 664 - commerce, 569-70 -gold, 564 - currency,