Japanese History: Origins to the Twelfth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

Dept of History Draft Syllabus (Cbcs)

RAJA NARENDRALAL KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) DEPT OF HISTORY DRAFT SYLLABUS (CBCS) I SEMESTER Course Course Title Credit Marks Total Th IM AM CC1T Greek and Roman Historians 6 60 10 5 75 CC2T Early Historic India 6 60 10 5 75 GE1T History of India From the earliest 6 60 10 5 75 times to C 300 BCE DSC History of India-I (Ancient India) 6 60 10 5 75 CC-1: Greek and Roman Historians C1T: Greek and Roman Historians Unit-I Module I New form of inquiry (historia) in Greece in the sixth century BCE 1.1 Logographers in ancient Greece. 1.2 Hecataeus of Miletus, the most important predecessor of Heredotus 1.3 Charon of Lampsacus 1.4 Xanthus of Lydia Module II Herodotus and his Histories 2.1 A traveller’s romance? 2.2 Herodotus’ method of history writing – his catholic inclusiveness 2.3 Herodotus’ originality as a historian – focus on the struggle between the East and the West Module III Thucydides: the founder of scientific history writing 3.1 A historiography on Thucydides 3.2 History of the Peloponnesian War - a product of rigorous inquiry and examination 3.3 Thucydides’ interpretive ability – his ideas of morality, Athenian imperialism, culture and democratic institutions 3.4 Description of plague in a symbolic way – assessment of the demagogues 3.5 A comparative study of the two greatest Greek historians Module IV Next generation of Greek historians 4.1 Xenophon and his History of Greece (Hellenica) 4.2 a description of events 410 BCE – 362 BCE 4.3 writing in the style of a high-class journalist – lack of analytical skill 4.5 Polybius and the “pragmatic” history 4.3 Diodorus Siculus and his Library of History – the Stoic doctrine of the brotherhood of man Unit II Roman Historiography Module I Development of Roman historiographical tradition 1.1 Quintus Fabius Pictor of late third century BCE and the “Graeci annals” – Rome’s early history in Greek. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

The Technological Imaginary of Imperial Japan, 1931-1945

THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron Stephen Moore August 2006 © 2006 Aaron Stephen Moore THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 Aaron Stephen Moore, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 “Technology” has often served as a signifier of development, progress, and innovation in the narrative of Japan’s transformation into an economic superpower. Few histories, however, treat technology as a system of power and mobilization. This dissertation examines an important shift in the discourse of technology in wartime Japan (1931-1945), a period usually viewed as anti-modern and anachronistic. I analyze how technology meant more than advanced machinery and infrastructure but included a subjective, ethical, and visionary element as well. For many elites, technology embodied certain ways of creative thinking, acting or being, as well as values of rationality, cooperation, and efficiency or visions of a society without ethnic or class conflict. By examining the thought and activities of the bureaucrat, Môri Hideoto, and the critic, Aikawa Haruki, I demonstrate that technology signified a wider system of social, cultural, and political mechanisms that incorporated the practical-political energies of the people for the construction of a “New Order in East Asia.” Therefore, my dissertation is more broadly about how power operated ideologically under Japanese fascism in ways other than outright violence and repression that resonate with post-war “democratic” Japan and many modern capitalist societies as well. This more subjective, immaterial sense of technology revealed a fundamental ambiguity at the heart of technology. -

Sartorius Thesis.Pdf (5.388Mb)

Material Memoir Master’s In Fine Arts Thesis Document Andrew Sartorius SUNY New Paltz Spring 2019 Material Memoir: Artist Statement My family owns a fifty acre plot of rolling red clay hills in West Virginia. When I return home, I dig clay, a pilgrimage to harvest from the strata of memory. This body of work explores the potential of wild West Virginia clay through the wood firing process. The kiln creates a dramatic range of effects as varying amounts of ash and heat amalgamate and give vitality to the wild clays I use. The kiln is my collaborator, a trusted but pleasantly unpredictable partner lending its voice to mine to create something made from a life of memory and memorial. Abstract Almost every Sunday of my childhood, my family gathered here for Sunday dinner. My family would meet on a rolling red clay hill topped with pin oak and pine forests, gentle fields, and barns that lean and sag with the weathering of time. My great grandmother lived on one side of the hill, and my grandparents on the other. My great grandmother’s parents started the tradition, and it followed the generations down to my grandmother and grandfather, Alice and Bernard Bosley, who took up the mantle during my childhood. In 2010, I moved to Japan to teach English at a rural high school in Kochi Prefecture. I returned to America in 2014 as a potter’s apprentice studying the traditional Japanese wood-fired ceramics with the ceramic artist Jeff Shapiro in Accord, New York. Since then, my grandparents have passed, but I find that they are more present in my thoughts than ever before. -

7.5 Heian Notes

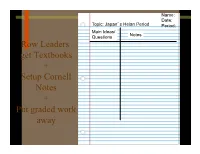

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Okakura Kakuzō's Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters

Asian Review of World Histories 2:1 (January 2014), 17-45 © 2014 The Asian Association of World Historians doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2014.2.1.017 Okakura Kakuzō’s Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters, Hegelian Dialectics and Darwinian Evolution Masako N. RACEL Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, United States [email protected] Abstract Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913), the founder of the Japan Art Institute, is best known for his proclamation, “Asia is One.” This phrase in his book, The Ideals of the East, and his connections to Bengali revolutionaries resulted in Okakura being remembered as one of Japan’s foremost Pan-Asianists. He did not, how- ever, write The Ideals of the East as political propaganda to justify Japanese aggression; he wrote it for Westerners as an exposition of Japan’s aesthetic heritage. In fact, he devoted much of his life to the preservation and promotion of Japan’s artistic heritage, giving lectures to both Japanese and Western audi- ences. This did not necessarily mean that he rejected Western philosophy and theories. A close examination of his views of both Eastern and Western art and history reveals that he was greatly influenced by Hegel’s notion of dialectics and the evolutionary theories proposed by Darwin and Spencer. Okakura viewed cross-cultural encounters to be a catalyst for change and saw his own time as a critical point where Eastern and Western history was colliding, caus- ing the evolution of both artistic cultures. Key words Okakura Kakuzō, Okakura Tenshin, Hegel, Darwin, cross-cultural encounters, Meiji Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:32:22PM via free access 18 | ASIAN REVIEW OF WORLD HISTORIES 2:1 (JANUARY 2014) In 1902, a man dressed in an exotic cloak and hood was seen travel- ing in India. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72474-6 — an Introduction to Japanese Society Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72474-6 — An Introduction to Japanese Society Yoshio Sugimoto Index More Information Index Abe, Shinz¯o,236, 303, 312 alternative culture, 285 abilities, of employees, 116–17 characteristics, 287 abortion, 186–8 communes and the natural economy, 299–300 academic world system, 52–3 Cool Japan as, 311 achieved status, 73–4, 81 countercultural events and performances, 298–9 Act on Land and Building Leases (1991), 122 historical examples, 297 Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation local resident–volunteer support movements as, and Advancement in the Workplace (2016), 325 182 mini-communication media and online papers, activism, see resident movements; social 297–8 movements nature of, 297 administrative guidance (gyosei¯ shido¯), 232, 235–6, social formations producing, 286 338 amae (active dependency), 29, 43, 51 administrative systems amakudari (descending from heaven), 232–5, 251 during Heian period, 9 Amaterasu Ōmikami, 6–7, 267 during Kamakura period, 10 ambiguity, manipulation of, 337–8 during Yamato period, 7 Ame no Uzume, 6 adoption, 196 Ampo struggle, 318, 321 AEON, 110 ancestor worship, 266, 281, 295 aging society, 47–8 animators, working conditions, 307 declining birth rate and, 86–7 anime, 27–8, 46–7, 302, 311 life expectancy in, 84–6 animism, 203, 266–7 rise in volunteering and, 323 annual leave, 120 woman’s role as caregiver in, 181 anomie (normlessness), 48 Agon-shu¯ (Agon sect), 273 anti-development protests, 324–5 agricultural cooperatives, 326 anti-nuclear demonstrations, 92, 317–21 -

The Karin Ikebana Exhibition

Sairyuka - Art and ancient Asian philosophy rooted in nature KARIN-en vol.6 Sairyuka No. 35 Supplementary Karin-en News No. 6, January 2018 Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels ... The Karin Ikebana Exhibition Kanazawa / Tokyo “ Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels - The Karin Ikebana Exhibitions” were held in Kanazawa and Tokyo, co- inciding with the Hina festival and Boy’s Day celebration (Sairyuka No. 35). This page and the next show designs from the Tokyo exhibition. Sairyuka - Ikebana of the Wind Camellia (single-variant); by Karin Painting (hanging scroll) - “Sea bream”; by Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Boat-form ceramic vase and square/circular stand (thick board) Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda (ceramics), Kazuhiko Tada (stand) Koryu Association, Komagome, Tokyo 23 November Held together with the Koryu Ikebana Exhi- bition (continued on p2) Jiyuka (versatile arrangement); by Risei Morikawa Pine, camellia, eucalyptus, lily, soaproot, kori willow, other Vessel: Reika - beech, other; by Box-form ceramic vase Design by Karin Hosei Sakamoto Painting Production by Yatomi Maeda (hanging scroll) - “frog”; by Positioned at the venue entrance Karin Mounting by Akira Na- gashima Vessel: Ceramic “ kagamigata ” (parabolic) vase Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda 1 The Karin Ikebana Exhibition 23 November23 Continued from page page 1 from Continued KoryuAssociation, Komagome, Sairyuka - Five Ikebana: Camellia (single tone) (From left: Wind Ikebana, Water Ikebana, Sword Ikebana, Earth Ikebana, Fire Ikebana): by Karin, Kyuuka Yamaki, Kyuuka Higashimori Paintings (hanging scroll) - From left: Enso-Wind, Enso-Water, Enso-Sword, Enso-Earth, Enso-Fire: Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Square-circular ceramic vase Design by Karin Tokyo Production by Yatomi Maeda The Tokyo “Karin Ikebana Exhibition” was held on 23 【Right】 November at the Koryu Reika - (Japanese yew), other: by Association in Komagome, Ribin Okamoto alongside the established Painting (hanging scroll) - “sword”; Koryu Shoseikai Ikebana by Karin exhibition. -

Jingu Kogo Ema in Southwestern Japan Reflections and Anticipations of the Seikanron Debate in the Late Tokugawa and Early Meiji Period

R ic h a r d W A n d e r s o n Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Jingu Kogo Ema in Southwestern Japan Reflections and Anticipations of the Seikanron Debate in the Late Tokugawa and Early Meiji Period Abstract Preliminary investigation suggests that ema (votive paintings) featuring a fourth-century legendary empress (Jingu Kogo) of Japan as their subject were used by local elites in southwestern Japan in the nineteenth century to justify the need for overseas expansion — in particular the need for an invasion of Korea. Jingu Kogo ema exhibit two basic motifs, both of which allude to her alleged invasion of Korea. From ema surveys in Yamaguchi Prefecture and Fukuoka Prefecture I have discovered that a geographical and temporal correlation emerges from the distribution of these ema. I contend that the prevalence of different motifs in these areas, and the dating suggest that local elites were using Jingu Kogo ema as an iconographic “text” to discuss and comment on the advisa bility/feasibility of invading Korea {seikanron). This spillover of political themes into religious artifacts is an interesting and potentially very fruitful area of study that has received inadequate attention. Keywords: ema— seikanron— Jingu Kogo— folk art— Japanese-Korean relations— min- shushi Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 61,2002: 247-270 APANESE-KOREAN RELATIONS have evolved over a long and often con tentious history.1 The record of nearly two thousand years of contact between Japan and Korea includes the introduction of Buddhism into JJapan through Korea; the exchange of tribute and trade; repeated raids by pirates; two invasions and occupations of portions of the Korean peninsula (from the fourth to sixth centuries and in the latter part of the sixteenth cen tury);2 a major debate by Japanese government officials in the 1870s over whether to invade Korea a third time; and, finally, the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1905 until the restoration of its independence in 1945.