Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

MTO 10.1: Wibberley, Syntonic Tuning

Volume 10, Number 1, February 2004 Copyright © 2004 Society for Music Theory Roger Wibberley KEYWORDS: Aristoxenus, comma, Ganassi, Jachet, Josquin, Ptolemy, Rore, tetrachord, Vesper-Psalms, Willaert, Zarlino ABSTRACT: This Essay makes at the outset an important (if somewhat controversial) assumption. This is that Syntonic tuning (Just Intonation) is not—though often presumed to be so—primarily what might be termed “a performer’s art.” On the contrary it is a composer’s art. As with the work of any composer from any period, it is the performer’s duty to render the music according to the composer’s wishes as shown through the evidence. Such evidence may be indirect (perhaps documentary) or it may be explicitly structural (to be revealed through analysis). What will be clear is the fallacy of assuming that Just Intonation can (or should) be applied to any music rather than only to that which was specifically designed by the composer for the purpose. How one can deduce whether a particular composer did, or did not, have the sound world of Just Intonation (henceforward referred to as “JI”) in mind when composing will also be explored together with a supporting analytical rationale. Musical soundscape (especially where voices are concerned) means, of course, incalculably more than mere “accurate intonation of pitches” (which alone is the focus of this essay): its color derives not only from pitch combination, but more importantly from the interplay of vocal timbres. These arise from the diverse vowel sounds and consonants that give life, color and expression. The audio examples provided here are therefore to be regarded as “playbacks” and no claim is being implied or intended that they in any way stand up as “performances.” Some care, nonetheless, has been taken to make them as acceptable as is possible with computer-generated sounds. -

MTO 20.2: Wild, Vicentino's 31-Tone Compositional Theory

Volume 20, Number 2, June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Genus, Species and Mode in Vicentino’s 31-tone Compositional Theory Jonathan Wild NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.wild.php KEYWORDS: Vicentino, enharmonicism, chromaticism, sixteenth century, tuning, genus, species, mode ABSTRACT: This article explores the pitch structures developed by Nicola Vicentino in his 1555 treatise L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica . I examine the rationale for his background gamut of 31 pitch classes, and document the relationships among his accounts of the genera, species, and modes, and between his and earlier accounts. Specially recorded and retuned audio examples illustrate some of the surviving enharmonic and chromatic musical passages. Received February 2014 Table of Contents Introduction [1] Tuning [4] The Archicembalo [8] Genus [10] Enharmonic division of the whole tone [13] Species [15] Mode [28] Composing in the genera [32] Conclusion [35] Introduction [1] In his treatise of 1555, L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (henceforth L’Antica musica ), the theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino describes a tuning system comprising thirty-one tones to the octave, and presents several excerpts from compositions intended to be sung in that tuning. (1) The rich compositional theory he develops in the treatise, in concert with the few surviving musical passages, offers a tantalizing glimpse of an alternative pathway for musical development, one whose radically augmented pitch materials make possible a vast range of novel melodic gestures and harmonic successions. -

The Karin Ikebana Exhibition

Sairyuka - Art and ancient Asian philosophy rooted in nature KARIN-en vol.6 Sairyuka No. 35 Supplementary Karin-en News No. 6, January 2018 Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels ... The Karin Ikebana Exhibition Kanazawa / Tokyo “ Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels - The Karin Ikebana Exhibitions” were held in Kanazawa and Tokyo, co- inciding with the Hina festival and Boy’s Day celebration (Sairyuka No. 35). This page and the next show designs from the Tokyo exhibition. Sairyuka - Ikebana of the Wind Camellia (single-variant); by Karin Painting (hanging scroll) - “Sea bream”; by Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Boat-form ceramic vase and square/circular stand (thick board) Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda (ceramics), Kazuhiko Tada (stand) Koryu Association, Komagome, Tokyo 23 November Held together with the Koryu Ikebana Exhi- bition (continued on p2) Jiyuka (versatile arrangement); by Risei Morikawa Pine, camellia, eucalyptus, lily, soaproot, kori willow, other Vessel: Reika - beech, other; by Box-form ceramic vase Design by Karin Hosei Sakamoto Painting Production by Yatomi Maeda (hanging scroll) - “frog”; by Positioned at the venue entrance Karin Mounting by Akira Na- gashima Vessel: Ceramic “ kagamigata ” (parabolic) vase Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda 1 The Karin Ikebana Exhibition 23 November23 Continued from page page 1 from Continued KoryuAssociation, Komagome, Sairyuka - Five Ikebana: Camellia (single tone) (From left: Wind Ikebana, Water Ikebana, Sword Ikebana, Earth Ikebana, Fire Ikebana): by Karin, Kyuuka Yamaki, Kyuuka Higashimori Paintings (hanging scroll) - From left: Enso-Wind, Enso-Water, Enso-Sword, Enso-Earth, Enso-Fire: Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Square-circular ceramic vase Design by Karin Tokyo Production by Yatomi Maeda The Tokyo “Karin Ikebana Exhibition” was held on 23 【Right】 November at the Koryu Reika - (Japanese yew), other: by Association in Komagome, Ribin Okamoto alongside the established Painting (hanging scroll) - “sword”; Koryu Shoseikai Ikebana by Karin exhibition. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan

Educating Minds and Hearts to Change the World A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Volume IX ∙ Number 2 June ∙ 2010 Pacific Rim Copyright 2010 The Sea Otter Islands: Geopolitics and Environment in the East Asian Fur Trade >>..............................................................Richard Ravalli 27 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Shadows of Modernity: Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan Editorial >>...............................................................Nicholas Mucks 36 Consultants Barbara K. Bundy East Timor and the Power of International Commitments in the American Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Decision Making Process >>.......................................................Christopher R. Cook 43 Editorial Board Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Syed Hussein Alatas: His Life and Critiques of the Malaysian New Economic Mark Mir Policy Noriko Nagata Stephen Roddy >>................................................................Choon-Yin Sam 55 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick Betel Nut Culture in Contemporary Taiwan >>..........................................................................Annie Liu 63 A Note from the Publisher >>..............................................Center for the Pacific Rim 69 Asia Pacific: Perspectives Asia Pacific: Perspectives is a peer-reviewed journal published at least once a year, usually in April/May. It Center for the Pacific Rim welcomes submissions from all fields of the social sciences and the humanities with relevance to the Asia Pacific 2130 Fulton St, LM280 region.* In keeping with the Jesuit traditions of the University of San Francisco, Asia Pacific: Perspectives com- San Francisco, CA mits itself to the highest standards of learning and scholarship. 94117-1080 Our task is to inform public opinion by a broad hospitality to divergent views and ideas that promote cross-cul- Tel: (415) 422-6357 Fax: (415) 422-5933 tural understanding, tolerance, and the dissemination of knowledge unreservedly. -

250 + Musical Scales and Scalecodings

250 + Musical Scales and Scalecodings Number Note Names Of Notes Ascending Name Of Scale In Scale from C ScaleCoding Major Suspended 4th Chord 4 C D F G 3/0/2 Major b7 Suspend 4th Chord 4 C F G Bb 3/0/3 Major Pentatonic 5 C D E G A 4/0/1 Ritusen Japan, Scottish Pentatonic 5 C D F G A 4/0/2 Egyptian \ Suspended Pentatonic 5 C D F G Bb 4/0/3 Blues Pentatonic Minor, Hard Japan 5 C Eb F G Bb 4/0/4 Major 7-b5 Chord \ Messiaen Truncated Mode 4 C Eb G Bb 4/3/4 Minor b7 Chord 4 C Eb G Bb 4/3/4 Major Chord 3 C E G 4/34/1 Eskimo Tetratonic 4 C D E G 4/4/1 Lydian Hexatonic 6 C D E G A B 5/0/1 Scottish Hexatonic 6 C D E F G A 5/0/2 Mixolydian Hexatonic 6 C D F G A Bb 5/0/3 Phrygian Hexatonic 6 C Eb F G Ab Bb 5/0/5 Ritsu 6 C Db Eb F Ab Bb 5/0/6 Minor Pentachord 5 C D Eb F G 5/2/4 Major 7 Chord 4 C E G B 5/24/1 Phrygian Tetrachord 4 C Db Eb F 5/24/6 Dorian Tetrachord 4 C D Eb F 5/25/4 Major Tetrachord 4 C D E F 5/35/2 Warao Tetratonic 4 C D Eb Bb 5/35/4 Oriental 5 C D F A Bb 5/4/3 Major Pentachord 5 C D E F G 5/5/2 Han-Kumo? 5 C D F G Ab 5/23/5 Lydian, Kalyan F to E ascending naturals 7 C D E F# G A B 6/0/1 Ionian, Major, Bilaval C to B asc. -

ANNEXURE Credo Theory of Music Training Programme GRADE 5 by S

- 1 - ANNEXURE Credo Theory of Music training programme GRADE 5 By S. J. Cloete Copyright reserved © 2017 BLUES (JAZZ). (Unisa learners only) WHAT IS THE BLUES? The Blues is a musical genre* originated by African Americans in the Deep South of the USA around the end of the 19th century. The genre developed from roots in African musical traditions, African-American work songs, spirituals and folk music. The first appearance of the Blues is often dated to after the ending of slavery in America. The slavery was a sad time in history and this melancholic sound is heard in Blues music. The Blues, ubiquitous in jazz and rock ‘n’ roll music, is characterized by the call-and- response* pattern, the blues scale (which you are about to learn) and specific chord progressions*, of which the twelve-bar blues* is the most common. Blue notes*, usually 3rds or 5ths flattened in pitch, are also an essential part of the sound. A swing* rhythm and walking bass* are commonly used in blues, country music, jazz, etc. * Musical genre: It is a conventional category that identifies some music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions, e.g. the blues, or classical music or opera, etc. They share a certain “basic musical language”. * Call-and-response pattern: It is a succession of two distinct phrases, usually played by different musicians (groups), where the second phrase is heard as a direct commentary on or response to the first. It can be traced back to African music. * Chord progressions: The blues follows a certain chord progression and the th th 7 b harmonic 7 (blues 7 ) is used much of the time (e.g. -

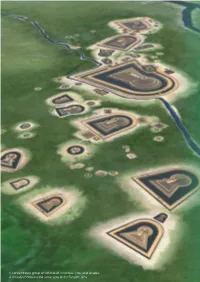

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale J. N. Hooker Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] May 2017 Abstract We analyze results of a search for alternative musical scales that share the main advantages of classical scales: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an un- derlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. The search is based on combinatorics and a constraint programming model that assigns frequency ratios to intervals. We find that certain 11-note scales on a 19-note chromatic stand out as superior to all others. These scales enjoy harmonic and structural possibilities that go significantly beyond what is available in classical scales and therefore provide a possible medium for innovative musical composition. 1 Introduction The classical major and minor scales of Western music have two attractive characteristics: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an underlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. Simple ratios allow for rich and intelligible harmonies, while multiple keys greatly expand possibilities for complex musical structure. While these tra- ditional scales have provided the basis for a fabulous outpouring of musical creativity over several centuries, one might ask whether they provide the natural or inevitable framework for music. Perhaps there are alternative scales with the same favorable characteristics|simple ratios and multiple keys|that could unleash even greater creativity. This paper summarizes the results of a recent study [8] that undertook a systematic search for musically appealing alternative scales. The search 1 restricts itself to diatonic scales, whose adjacent notes are separated by a whole tone or semitone. -

Specifying Spectra for Musical Scales William A

Specifying spectra for musical scales William A. Setharesa) Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706-1691 ~Received 5 July 1996; accepted for publication 3 June 1997! The sensory consonance and dissonance of musical intervals is dependent on the spectrum of the tones. The dissonance curve gives a measure of this perception over a range of intervals, and a musical scale is said to be related to a sound with a given spectrum if minima of the dissonance curve occur at the scale steps. While it is straightforward to calculate the dissonance curve for a given sound, it is not obvious how to find related spectra for a given scale. This paper introduces a ‘‘symbolic method’’ for constructing related spectra that is applicable to scales built from a small number of successive intervals. The method is applied to specify related spectra for several different tetrachordal scales, including the well-known Pythagorean scale. Mathematical properties of the symbolic system are investigated, and the strengths and weaknesses of the approach are discussed. © 1997 Acoustical Society of America. @S0001-4966~97!05509-4# PACS numbers: 43.75.Bc, 43.75.Cd @WJS# INTRODUCTION turn closely related to Helmholtz’8 ‘‘beat theory’’ of disso- nance in which the beating between higher harmonics causes The motion from consonance to dissonance and back a roughness that is perceived as dissonance. again is a standard feature of most Western music, and sev- Nonharmonic sounds can have dissonance curves that eral attempts have been made to explain, define, and quantify differ dramatically from Fig. -

View the Analyses of Webern’S Pieces

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 24, 2005 __________________ I, Hyekyung Park __________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Music in: Music Theory It is entitled: Transformational Networks and Voice Leadings in the First Movement of Webern’s Cantata No. 1, Op. 29. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Steven Cahn Dr. David Berry Dr. Earl Rivers TRANSFORMATIONAL NETWORKS AND VOICE LEADINGS IN THE FIRST MOVEMENT OF WEBERN’S CANTATA No. 1, OP. 29. A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Hyekyung Park B.M. Ewha Womans Univerisity, S. Korea 2002 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract This thesis examines the use of transformation approaches for Anton Webern’s the First Cantata Op.29, No.1. The thesis is divided primarily into two parts: the summary of a theory of transformation and analyses of Op.29, No.1, which is studied in a transformation attitude. After presenting the introduction, Chapter 1 summarizes a theory of transformation based on David Lewin’s analyses about Webern’s works, and it researches three different approaches of voice leading, especially focusing on Joseph Straus’s transformational attitude. Before getting to the analyses, Chapter 2 presents the background of Webern’s Cantatas No.1, Op.29 as a basic for understanding this piece. The main contents of Chapter 2 are Webern’s thought about Op.29 and the reason why he collected three different poems as one work.