The Heian Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Timelines and Maps Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books English Version © Keio University Timelines and Maps East Asian History at a Glance Books are part of the flow of history. But it is not only about Japanese history. Many books travel over the sea time to time for several reasons and a lot of knowledge and information comes and go with books. In this course, you’ll see books published in Japan as well as ones come from China and Korea. Let’s take a look at the history in East Asia. You do not have to remember the names of the historical period but please refer to this page for reference. Japanese History Overview This is a list of the main periods in Japanese history. This may be a useful reference as we proceed in the course. Period Name of Era Name of Era - mid-3rd c. CE Yayoi 弥生 mid-3rd c. CE - 7th c. CE Kofun (Tomb period) 古墳 592 - 710 Asuka 飛鳥 710-794 Nara 奈良 794 - 1185 Heian 平安 1185 - 1333 Kamakura 鎌倉 Nanboku-chō 1333 - 1392 (Southern and Northern Courts period) 南北朝 1392 - 1573 Muromachi 室町 1573 - 1603 Azuchi-Momoyama 安土桃山 1603 - 1868 Edo 江戸 1868 - 1912 Meiji 明治 Era names (Nengō) in Edo Period There were several era names (nengo, or gengo) in Edo period (1603 ~ 1868) and they are sometimes used in the description of the old books and materials, especially Week 2 and Week 4. Here is the list of the era names in Edo period for your convenience; 1 SINO-JAPANESE INTERACTIONS THROUGH RARE BOOKS KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University Timelines and Maps Start Era name English Start Era name English 1596 慶長 Keichō 1744 延享 Enkyō -

Working Papers in Linguistics and Oriental Studies 1

Universita’ degli Studi di Firenze Dipartimento di Lingue, Letterature e Studi Interculturali Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna: Collana, Riviste e Laboratorio Quaderni di Linguistica e Studi Orientali Working Papers in Linguistics and Oriental Studies 1 Editor M. Rita Manzini firenze university press 2015 Quaderni di Linguistica e Studi Orientali / Working Papers in Linguistics and Oriental Studies - n. 1, 2015 ISSN 2421-7220 ISBN 978-88-6655-832-3 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/QULSO-2421-7220-1 Direttore Responsabile: Beatrice Töttössy CC 2015 Firenze University Press La rivista è pubblicata on-line ad accesso aperto al seguente indirizzo: www.fupress.com/bsfm-qulso The products of the Publishing Committee of Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna: Collana, Riviste e Laboratorio (<http://www.lilsi.unifi.it/vp-82-laboratorio-editoriale-open-access-ricerca- formazione-e-produzione.html>) are published with financial support from the Department of Languages, Literatures and Intercultural Studies of the University of Florence, and in accordance with the agreement, dated February 10th 2009 (updated February 19th 2015), between the De- partment, the Open Access Publishing Workshop and Firenze University Press. The Workshop promotes the development of OA publishing and its application in teaching and career advice for undergraduates, graduates, and PhD students in the area of foreign languages and litera- tures, and of social studies, as well as providing training and planning services. The Workshop’s publishing team are responsible for the editorial workflow of all the volumes and journals pub- lished in the Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna series. QULSO employs the double-blind peer review process. -

Guts and Tears Kinpira Jōruri and Its Textual Transformations

Guts and Tears Kinpira Jōruri and Its Textual Transformations Janice Shizue Kanemitsu In seventeenth-century Japan, dramatic narratives were being performed under drastically new circumstances. Instead of itinerant performers giving performances at religious venues in accordance with a ritual calendar, professionals staged plays at commercial, secular, and physically fixed venues. Theaters contracted artists to perform monthly programs (that might run shorter or longer than a month, depending on a given program’s popularity and other factors) and operated on revenues earned by charging theatergoers admission fees. A theater’s survival thus hinged on staging hit plays that would draw audiences. And if a particular cast of characters was found to please crowds, producing plays that placed the same characters in a variety of situations was one means of ensuring a full house. Kinpira jōruri 金平浄瑠璃 enjoyed tremendous though short-lived popularity as a form of puppet theater during the mid-1600s. Though its storylines lack the nuanced sophistication of later theatrical narra- tives, Kinpira jōruri offers a vivid illustration of how theater interacted with publishing in Japan during the early Tokugawa 徳川 period. This essay begins with an overview of Kinpira jōruri’s historical background, and then discusses the textualization of puppet theater plays. Although Kinpira jōruri plays were first composed as highly masculinized period pieces revolving around political scandals, they gradually transformed to incorporate more sentimentalism and female protagonists. The final part of this chapter will therefore consider the fundamental characteristics of Kinpira jōruri as a whole, and explore the ways in which the circulation of Kinpira jōruri plays—as printed texts— encouraged a transregional hybridization of this theatrical genre. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

The Case of Sugawara No Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho''

Ideology and Historiography : The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho'' 著者 PLUTSCHOW Herbert 会議概要(会議名, Historiography and Japanese Consciousness of 開催地, 会期, 主催 Values and Norms, カリフォルニア大学 サンタ・ 者等) バーバラ校, カリフォルニア大学 ロサンゼルス校, 2001年1月 page range 133-145 year 2003-01-31 シリーズ 北米シンポジウム 2000 International Symposium in North America 2014 URL http://doi.org/10.15055/00001515 Ideology and Historiography: The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the Nihongiryaku, Fusi Ryakki and the Gukanshd Herbert PLUTSCHOW University of California at Los Angeles To make victims into heroes is a Japanese cultural phenomenon intimately relat- ed to religion and society. It is as old as written history and survives into modem times. Victims appear as heroes in Buddhist, Shinto, and Shinto-Buddhist cults and in numer- ous works of Japanese literature, theater and the arts. In a number of articles I have pub- lished on this subject,' I tried to offer a religious interpretation, emphasizing the need to placate political victims in order to safeguard the state from their wrath. Unappeased political victims were believed to seek revenge by harming the living, causing natural calamities, provoking social discord, jeopardizing the national welfare. Beginning in the tenth century, such placation took on a national importance. Elsewhere I have tried to demonstrate that the cult of political victims forced political leaders to worship their for- mer enemies in a cult providing the religious legitimization, that is, the mainstay of their power.' The reason for this was, as I demonstrated, the attempt leaders made to control natural forces through the worship of spirits believed to influence them. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

The Shôkyû Version of the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki: a Brief Introduction to Its Content and Function

Eras Edition 11, November 2009 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/publications/eras The Shôkyû version of the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki: A brief introduction to its content and function Sara L. Sumpter (University of Pittsburgh) Abstract: This article examines the political and social atmosphere surrounding the production of the thirteenth-century hand scroll Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Shrine), which depicts the life, death and posthumous revenge of the ninth-century courtier Sugawara no Michizane. The article combines an analysis of the content and religious iconography of the scroll, a study of early Japanese beliefs in angry spirits of the dead, and a narration of the actual life of Michizane in an attempt to produce a sketch of the rituals and superstitions of Heian and early Kamakura period Japanese society, and to suggest possible functions of the hand scroll that complement them. The hand scroll sets collectively known as the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Shrine) each tell the story of the life and death of the ninth- century courtier and poet, Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), and of the posthumous revenge undertaken by his vengeful spirit (onryô). According to the scrolls, Michizane was falsely accused of treason by rivals at the Heian court who were jealous of his astronomical rise to power. He was exiled to Dazaifu on the island of Kyushu in 901 and died there two years later in despair. His spirit persisted in seeking retribution against his enemies and in reclaiming his position and honours. He is said to have stalked his numerous rivals in the form of the thunder god (raijin) before ultimately revealing to a frightened court, through a series of intermediaries, the means of his pacification: deification and worship at the Kitano Shrine in Kyoto.1 Today the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (hereafter referred to as the Tenjin scrolls) number more than thirty extant examples, ranging in date from the early thirteenth century to the nineteenth century. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bk827db Author Chudnow, Matthew Thomas Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. -

7.5 Heian Notes

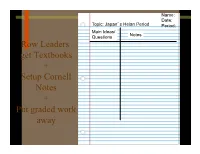

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Ki No Tsurayuki a Poszukiwanie Tożsamości Kulturowej W Literaturze Japońskiej X Wieku

Title: Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku Author: Krzysztof Olszewski Citation style: Olszewski Krzysztof. (2003). Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku. Kraków : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku Literatura, język i kultura Japonii Krzysztof Olszewski Ki no Tsurayuki a poszukiwanie tożsamości kulturowej w literaturze japońskiej X wieku WYDAWNICTWO UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO Seria: Literatura, język i kultura Japonii Publikacja finansowana przez Komitet Badań Naukowych oraz ze środków Instytutu Filologii Orientalnej oraz Wydziału Filologicznego Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego RECENZENCI Romuald Huszcza Alfred M. Majewicz PROJEKT OKŁADKI Marcin Bruchnalski REDAKTOR Jerzy Hrycyk KOREKTOR Krystyna Dulińska © Copyright by Krzysztof Olszewski & Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Wydanie I, Kraków 2003 All rights reserved ISBN 83-233-1660-0 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Dystrybucja: ul. Bydgoska 19 C, 30-056 Kraków Tel. (012) 638-77-83, 636-80-00 w. 2022, 2023, fax (012) 430-19-95 Tel. kom. 0604-414-568, e-mail: wydaw@if. uj. edu.pl http: //www.wuj. pl Konto: BPH PBK SA IV/O Kraków nr 10601389-320000478769 A MOTTO Księżyc, co mieszka w wodzie, Nabieram w dłonie Odbicie jego To jest, to niknie znowu - Świat, w którym przyszło mi żyć. Ki no Tsurayuki, testament poetycki' W świątyni w Iwai Będę się modlił za Ciebie I czekał całe wieki. Choć -

A Garden in Uji Embodying the Yearning for the Paradise in The

II SUGIMOTO Hiroshi A Garden in Uji Embodying the Yearning for the Paradise in the West – Byôdô-in Garden – SUGIMOTO Hiroshi Sub-Manager, Historic City Planning Promotion Section, Uji City, JAPAN 1. Creation of Byôdô-in (south-facing temple building) and a pond are located on In the Heian period (794 to 1185), Uji was developed the south-north axis extending from the Nan-mon (south in the southern Heian-kyô (present-day Kyôto) as a gate), and the pond is surrounded by the U shaped temple. residential suburb. The preceding building of Byôdô-in was Byôdô-in is significantly different in these features from the originally built in the early Heian period as a private villa for other two temples. The building style of the Phoenix Hall Minamoto no Tôru, which was later purchased by Fujiwara was taken over by Shôkômyô-in in Toba and Muryôkô-in in no Michinaga. After being bequeathed to his son Fujiwara Hiraizumi, exerting a significant impact on the development no Yorimichi, the villa was converted into a temple in 1052, of Jôdo temples in later years. which coincided with the beginning of the mappô, the age of the degeneration of the Buddha’s law. The main hall of the 2. Byôdô-in Garden villa was then renovated into a Buddhist sanctum and the It is obvious, both from records and the layout, that the Phoenix Hall (Hô-oh-dô) was added in the following year. Phoenix Hall is the main building of the Byôdô-in temple The Fujiwara clan continued expanding the building and, by complex.