The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: a Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Pas Sur La Neige

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Mystères limpides: Time and Transformation in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige Debussy est mystérieux, mais il est clair. —Vladimir Jankélévitch STEVEN RINGS Introduction: Secrets and Mysteries sive religious orders). Mysteries, by contrast, are fundamentally unknowable: they are mys- Vladimir Jankélévitch begins his 1949 mono- teries for all, and for all time. Death is the graph Debussy et le mystère by drawing a dis- ultimate mystery, its essence inaccessible to tinction between the secret and the mystery. the living. Jankélévitch proposes other myster- Secrets, per Jankélévitch, are knowable, but ies as well, some of them idiosyncratic: the they are known only to some. For those not “in mysteries of destiny, anguish, pleasure, God, on the secret,” the barrier to knowledge can love, space, innocence, and—in various forms— take many forms: a secret might be enclosed in time. (The latter will be of particular interest a riddle or a puzzle; it might be hidden by acts in this article.) Unlike the exclusionary secret, of dissembling; or it may be accessible only to the mystery, shared and experienced by all of privileged initiates (Jankélévitch cites exclu- humanity, is an agent of “sympathie fraternelle et . commune humilité.”1 An abbreviated version of this article was presented as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music collo- 1Vladimir Jankélévitch, Debussy et le mystère (Neuchâtel: quium series in November 2007. I am grateful for the Baconnière, 1949), pp. 9–12 (quote, p. 10). See also his later comments I received on that occasion from students and revision and expansion of the book, Debussy et le mystère faculty. -

Tonality in My Molto Adagio

Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Jorge Gómez Rodríguez Constructing Tonality in Molto Adagio A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Supervisor: Prof. Mart Humal Tallinn 2015 Abstract The focus of this paper is the analysis of the work for string ensemble entitled And Silence Eternal - Molto Adagio (Molto Adagio for short), written by the author of this thesis. Its originality lies in the use of a harmonic approach which is referred to as System of Harmonic Classes in this thesis. Owing to the relatively unconventional employment of otherwise traditional harmonic resources in this system, a preliminary theoretical framework needs to be put in place in order to construct an alternative tonal approach that may describe the pitch structure of the Molto Adagio. This will be the aim of Part 1. For this purpose, analytical notions such as symmetric pair, primary dominant factor, harmonic domain, and harmonic area will be introduced before the tonal character of the piece (or the extent to which Molto Adagio may be said to be tonal) can be assessed. A detailed description of how the composer envisions and constructs the system will follow, with special consideration to the place the major diatonic scale occupies in relation to it. Part 2 will engage in an analysis of the piece following the analytical directives gathered in Part 1. The concept of modular tonality, which incorporates the notions of harmonic area and harmonic classes, will be put forward as a heuristic term to account for the use of a linear analytical approach. -

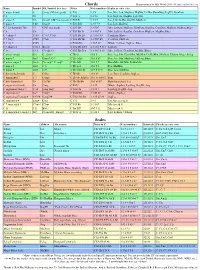

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg

Ryan Weber: Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg Grieg‘s intriguing statement, ―the realm of harmonies has always been my dream world,‖1 suggests the rather imaginative disposition that he held toward the roles of harmonic function within a diatonic pitch space. A great degree of his chromatic language is manifested in subtle interactions between different pitch spaces along the dualistic lines to which he referred in his personal commentary. Indeed, Grieg‘s distinctive style reaches beyond common-practice tonality in ways other than modality. Although his music uses a variety of common nineteenth- century harmonic devices, his synthesis of modal elements within a diatonic or chromatic framework often leans toward an aesthetic of Impressionism. This multifarious language is most clearly evident in the composer‘s abundant songs that span his entire career. Setting texts by a host of different poets, Grieg develops an approach to chromaticism that reflects the Romantic themes of death and despair. There are two techniques that serve to characterize aspects of his multi-faceted harmonic language. The first, what I designate ―chromatic juxtapositioning,‖ entails the insertion of highly chromatic material within ^ a principally diatonic passage. The second technique involves the use of b7 (bVII) as a particular type of harmonic juxtapositioning, for the flatted-seventh scale-degree serves as a congruent agent among the realms of diatonicism, chromaticism, and modality while also serving as a marker of death and despair. Through these techniques, Grieg creates a style that elevates the works of geographically linked poets by capitalizing on the Romantic/nationalistic themes. -

Development of Musical Scales in Europe

RABINDRA BHARATI UNIVERSITY VOCAL MUSIC DEPARTMENT COURSE - B.A. ( Compulsory Course ) (CBCS) 2020 Semester - II , Paper - I Teacher - Sri Partha Pratim Bhowmik History of Western Music Development of musical scales in Europe In the 8th century B.C., The musical atmosphere of ancient Greece introduced its development by the influence of then popular aristocratic music. That music was melody- based and the root of that music was rural folk-songs. In each and every country, the development of music was rooted in the folk-songs. The European Aristocratic Music of the Christian Era had been inspired by the developed Greek music. In the 5th century B.C. the renowned Greek Mathematician Pythagoras had first established a relation between science and music. Before him, the scale of Greek music was pentatonic. Pythagoras changed the scale into hexatonic pattern and later into heptatonic pattern. Greek musicians applied the alphabets to indicate the notes of their music. For the natural notes they used the alphabets in normal position and for the deformed notes, the alphabets turned upside down [deformed notes= Vikrita svaras]. The musical instruments, they had invented are – Aulos, Salpinx, pan-pipes, harp, lyre, syrinx etc. In the western music, the term ‘scale’ is derived from Latin word ‘scala’, ie, the ladder; scale means an ascent or descent formation of the musical notes. Each and every scale has a starting note, called ‘tonic note’ [‘tone - tonic’ not the Health-Tonic]. In the Ancient Greece, the musical scale had been formed with the help of lyre , a string instrument, having normally 5 or 6 or 7 strings. -

Debussy Préludes

Debussy Préludes Books I & II RALPH VOTAPEK ~ Debussy 24 Préludes Préludes, Book I (1909-1910) 37:13 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes (Lent et grave) 2:59 2 II. Voiles (Modéré) 3:09 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine (Animé) 2:07 4 IV. Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir (Modéré) 3:10 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri (Très modéré) 2:57 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige (Triste it lent) 3:47 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest (Animé et tumultueux) 3:23 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin (Très calme et doucement expressif) 2:29 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue (Modérément animé) 2:28 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie (Profondément calme) 5:54 11 XI. La danse de Puck (Capricieux et léger) 2:40 12 XII. Minstrels (Modéré) 2:10 Préludes, Book II (1912-1913) 36:04 13 I. Brouillards (Modéré) 2:38 14 II. Feuilles mortes (Lent et mélancolique) 2:55 15 III. La Puerta del Vino (Mouvement de Habanera) 3:19 16 IV. Les Fées sont d’exquises danseuses (Rapide et léger) 2:56 17 V. Bruyères (Calme) 2:42 18 VI. Général Lavine — eccentric (Dans le style et le mouvement d’un Cakewalk) 2:28 19 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune (Lent) 3:59 20 VIII. Ondine (Scherzando) 3:08 21 IX. Hommage à Samuel Pickwick, Esq., P.P.M.P.C. (Grave) 2:25 22 X. Canope (Très calme et doucement triste) 2:53 23 XI. -

GRAMMAR of SOLRESOL Or the Universal Language of François SUDRE

GRAMMAR OF SOLRESOL or the Universal Language of François SUDRE by BOLESLAS GAJEWSKI, Professor [M. Vincent GAJEWSKI, professor, d. Paris in 1881, is the father of the author of this Grammar. He was for thirty years the president of the Central committee for the study and advancement of Solresol, a committee founded in Paris in 1869 by Madame SUDRE, widow of the Inventor.] [This edition from taken from: Copyright © 1997, Stephen L. Rice, Last update: Nov. 19, 1997 URL: http://www2.polarnet.com/~srice/solresol/sorsoeng.htm Edits in [brackets], as well as chapter headings and formatting by Doug Bigham, 2005, for LIN 312.] I. Introduction II. General concepts of solresol III. Words of one [and two] syllable[s] IV. Suppression of synonyms V. Reversed meanings VI. Important note VII. Word groups VIII. Classification of ideas: 1º simple notes IX. Classification of ideas: 2º repeated notes X. Genders XI. Numbers XII. Parts of speech XIII. Number of words XIV. Separation of homonyms XV. Verbs XVI. Subjunctive XVII. Passive verbs XVIII. Reflexive verbs XIX. Impersonal verbs XX. Interrogation and negation XXI. Syntax XXII. Fasi, sifa XXIII. Partitive XXIV. Different kinds of writing XXV. Different ways of communicating XXVI. Brief extract from the dictionary I. Introduction In all the business of life, people must understand one another. But how is it possible to understand foreigners, when there are around three thousand different languages spoken on earth? For everyone's sake, to facilitate travel and international relations, and to promote the progress of beneficial science, a language is needed that is easy, shared by all peoples, and capable of serving as a means of interpretation in all countries. -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements

Gazi University Journal of Science Part B: Art, Humanities, Design And Planning GU J Sci Part:B 1(3):49-56 (2013) Use of Scale Modeling for Architectural Acoustic Measurements Ferhat ERÖZ 1,♠ 1 Atılım University, Department of Interior Architecture & Environmental Design Received: 09.07.2013 Accepted:01.10.2013 ABSTRACT In recent years, acoustic science and hearing has become important. Acoustic design tests used in acoustic devices is crucial. Sound propagation is a complex subject, especially inside enclosed spaces. From the 19th century on, the acoustic measurements and tests were carried out using modeling techniques that are based on room acoustic measurement parameters. In this study, the effects of architectural acoustic design of modeling techniques and acoustic parameters were investigated. In this context, the relationships and comparisons between physical, scale, and computer models were examined. Key words: Acoustic Modeling Techniques, Acoustics Project Design, Acoustic Parameters, Acoustic Measurement Techniques, Cavity Resonator. 1. INTRODUCTION (1877) “Theory of Sound”, acoustics was born as a science [1]. In the 20th century, especially in the second half, sound and noise concepts gained vast importance due to both A scientific context began to take shape with the technological and social advancements. As a result of theoretical sound studies of Prof. Wallace C. Sabine, these advancements, acoustic design, which falls in the who laid the foundations of architectural acoustics, science of acoustics, and the use of methods that are between 1898 and 1905. Modern acoustics started with related to the investigation of acoustic measurements, studies that were conducted by Sabine and auditory became important. Therefore, the science of acoustics quality was related to measurable and calculable gains more and more important every day. -

Nora-Louise Müller the Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet An

Nora-Louise Müller The Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet An Introduction to Acoustics and Playing Technique The Bohlen-Pierce scale was discovered in the 1970s and 1980s by Heinz Bohlen and John R. Pierce respectively. Due to a lack of instruments which were able to play the scale, hardly any compositions in Bohlen-Pierce could be found in the past. Just a few composers who work in electronic music used the scale – until the Canadian woodwind maker Stephen Fox created a Bohlen-Pierce clarinet, instigated by Georg Hajdu, professor of multimedia composition at Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg. Hence the number of Bohlen- Pierce compositions using the new instrument is increasing constantly. This article gives a short introduction to the characteristics of the Bohlen-Pierce scale and an overview about Bohlen-Pierce clarinets and their playing technique. The Bohlen-Pierce scale Unlike the scales of most tone systems, it is not the octave that forms the repeating frame of the Bohlen-Pierce scale, but the perfect twelfth (octave plus fifth), dividing it into 13 steps, according to various mathematical considerations. The result is an alternative harmonic system that opens new possibilities to contemporary and future music. Acoustically speaking, the octave's frequency ratio 1:2 is replaced by the ratio 1:3 in the Bohlen-Pierce scale, making the perfect twelfth an analogy to the octave. This interval is defined as the point of reference to which the scale aligns. The perfect twelfth, or as Pierce named it, the tritave (due to the 1:3 ratio) is achieved with 13 tone steps.