Orientalism As Represented in the Selected Piano Works by Claude Debussy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Pas Sur La Neige

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Mystères limpides: Time and Transformation in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige Debussy est mystérieux, mais il est clair. —Vladimir Jankélévitch STEVEN RINGS Introduction: Secrets and Mysteries sive religious orders). Mysteries, by contrast, are fundamentally unknowable: they are mys- Vladimir Jankélévitch begins his 1949 mono- teries for all, and for all time. Death is the graph Debussy et le mystère by drawing a dis- ultimate mystery, its essence inaccessible to tinction between the secret and the mystery. the living. Jankélévitch proposes other myster- Secrets, per Jankélévitch, are knowable, but ies as well, some of them idiosyncratic: the they are known only to some. For those not “in mysteries of destiny, anguish, pleasure, God, on the secret,” the barrier to knowledge can love, space, innocence, and—in various forms— take many forms: a secret might be enclosed in time. (The latter will be of particular interest a riddle or a puzzle; it might be hidden by acts in this article.) Unlike the exclusionary secret, of dissembling; or it may be accessible only to the mystery, shared and experienced by all of privileged initiates (Jankélévitch cites exclu- humanity, is an agent of “sympathie fraternelle et . commune humilité.”1 An abbreviated version of this article was presented as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music collo- 1Vladimir Jankélévitch, Debussy et le mystère (Neuchâtel: quium series in November 2007. I am grateful for the Baconnière, 1949), pp. 9–12 (quote, p. 10). See also his later comments I received on that occasion from students and revision and expansion of the book, Debussy et le mystère faculty. -

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell JAMES CLERK MAXWELL Perspectives on his Life and Work Edited by raymond flood mark mccartney and andrew whitaker 3 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries c Oxford University Press 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2013942195 ISBN 978–0–19–966437–5 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Debussy Préludes

Debussy Préludes Books I & II RALPH VOTAPEK ~ Debussy 24 Préludes Préludes, Book I (1909-1910) 37:13 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes (Lent et grave) 2:59 2 II. Voiles (Modéré) 3:09 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine (Animé) 2:07 4 IV. Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir (Modéré) 3:10 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri (Très modéré) 2:57 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige (Triste it lent) 3:47 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest (Animé et tumultueux) 3:23 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin (Très calme et doucement expressif) 2:29 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue (Modérément animé) 2:28 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie (Profondément calme) 5:54 11 XI. La danse de Puck (Capricieux et léger) 2:40 12 XII. Minstrels (Modéré) 2:10 Préludes, Book II (1912-1913) 36:04 13 I. Brouillards (Modéré) 2:38 14 II. Feuilles mortes (Lent et mélancolique) 2:55 15 III. La Puerta del Vino (Mouvement de Habanera) 3:19 16 IV. Les Fées sont d’exquises danseuses (Rapide et léger) 2:56 17 V. Bruyères (Calme) 2:42 18 VI. Général Lavine — eccentric (Dans le style et le mouvement d’un Cakewalk) 2:28 19 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune (Lent) 3:59 20 VIII. Ondine (Scherzando) 3:08 21 IX. Hommage à Samuel Pickwick, Esq., P.P.M.P.C. (Grave) 2:25 22 X. Canope (Très calme et doucement triste) 2:53 23 XI. -

The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2015 The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók David B. Hill James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, David B., "The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók" (2015). Dissertations. 38. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill A document submitted to the graduate faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2015 ! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! Figures…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…iii! ! Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...iv! ! Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1! ! PART!I:!SIMILARITIES!SHARED!BY!THE!TWO!NATIONLISTIC!COMPOSERS! ! A.!Origins…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! B.!Ties!to!Hungary…………………………………………………………………………………………...…..9! -

Liner Notes (PDF)

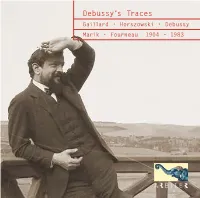

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Richard Goode, Piano

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, January 19, 2014, 3pm Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Préludes, Book I (1909–1910) Zellerbach Hall Danseuses de Delphes Voiles Le vent dans la plaine Richard Goode, piano Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir Les collines d’Anacapri Des pas sur la neige Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest PROGRAM La fille aux cheveux de lin La sérénade interrompue La Cathédrale engloutie La danse de Puck Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) From On an Overgrown Path (1901–1911) Minstrels Our Evenings A Blown-Away Leaf The program is subject to change. Come with Us! Good Night! Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837) Lebhaft Innig Mit humor Ungeduldig Einfach Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ Sehr rasch 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Nicht schnell Frisch This concert is dedicated to the memory of Donald Glaser (1926–2013). Lebhaft Balladenmäßig — Sehr rasch Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Einfach Mit Humor Wild und lustig Zart und singend Frisch Mit gutem Humor Wie aus der Ferne Nicht schnell INTERMISSION 2 3 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) birthday. “I would bind Jenůfa simply with the anguish”) and In Tears (“crying with a smile”). Linda Siegel described as vacillating between Selections from On an Overgrown Path black ribbon of the long illness, suffering and After On an Overgrown Path was published in “fits of depression with complete loss of reality laments of my daughter, Olga,” Janáček con- 1911, Janáček composed a second series of aph- and periods of seemingly placid adjustment to Composed in 1901–1902, 1908, and 1911. -

7'Tie;T;E ~;&H ~ T,#T1tmftllsieotog

7'tie;T;e ~;&H ~ t,#t1tMftllSieotOg, UCLA VOLUME 3 1986 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark E. Forry Anne Rasmussen Daniel Atesh Sonneborn Jane Sugarman Elizabeth Tolbert The Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology is an annual publication of the UCLA Ethnomusicology Students Association and is funded in part by the UCLA Graduate Student Association. Single issues are available for $6.00 (individuals) or $8.00 (institutions). Please address correspondence to: Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology Department of Music Schoenberg Hall University of California Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Standing orders and agencies receive a 20% discount. Subscribers residing outside the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico, please add $2.00 per order. Orders are payable in US dollars. Copyright © 1986 by the Regents of the University of California VOLUME 3 1986 CONTENTS Articles Ethnomusicologists Vis-a-Vis the Fallacies of Contemporary Musical Life ........................................ Stephen Blum 1 Responses to Blum................. ....................................... 20 The Construction, Technique, and Image of the Central Javanese Rebab in Relation to its Role in the Gamelan ... ................... Colin Quigley 42 Research Models in Ethnomusicology Applied to the RadifPhenomenon in Iranian Classical Music........................ Hafez Modir 63 New Theory for Traditional Music in Banyumas, West Central Java ......... R. Anderson Sutton 79 An Ethnomusicological Index to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Part Two ............ Kenneth Culley 102 Review Irene V. Jackson. More Than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians ....................... Norman Weinstein 126 Briefly Noted Echology ..................................................................... 129 Contributors to this Issue From the Editors The third issue of the Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology continues the tradition of representing the diversity inherent in our field. -

Technical Analysis on HW Ernst's Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple

Technical Analysis on Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst’s Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple Voices In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music Violin by Shang Jung Lin M.M. The Boston Conservatory November 2019 Committee Chair: Won-Bin Yim, D.M.A. Abstract Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst was a Moravian violinist and composer who lived between 1814-1865. He was a friend of Brahms, collaborator with Mendelssohn, and was admired by Berlioz and Joachim. He was known as a violin virtuoso and composed many virtuosic works including an arrangement of Schubert’s Erlkönig for solo violin. The focus of this document will be on his Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple Voices (also known as the Six Polyphonic Etudes). These pieces were published without opus number around 1862-1864. The etudes combine many different technical challenges with musical sensitivity. They were so difficult that the composer never gave a public performance of them. No. 6 is the most famous of the set, and has been performed by soloists in recent years. Ernst takes the difficulty level to the extreme and combines different layers of techniques within one hand. For example, the second etude has a passage that combines chords and left-hand pizzicato, and the sixth etude has a passage that combines harmonics with double stops. Etudes from other composers might contain these techniques but not simultaneously. The polyphonic nature allows for this layering of difficulties in Ernst’s Six Polyphonic Etudes. -

Interval Cycles and the Emergence of Major-Minor Tonality

Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 5, No. 3, 2010 Modes on the Move: Interval Cycles and the Emergence of Major-Minor Tonality MATTHEW WOOLHOUSE Centre for Music and Science, Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: The issue of the emergence of major-minor tonality is addressed by recourse to a novel pitch grouping process, referred to as interval cycle proximity (ICP). An interval cycle is the minimum number of (additive) iterations of an interval that are required for octave-related pitches to be re-stated, a property conjectured to be responsible for tonal attraction. It is hypothesised that the actuation of ICP in cognition, possibly in the latter part of the sixteenth century, led to a hierarchy of tonal attraction which favoured certain pitches over others, ostensibly the tonics of the modern major and minor system. An ICP model is described that calculates the level of tonal attraction between adjacent musical elements. The predictions of the model are shown to be consistent with music-theoretic accounts of common practice period tonality, including Piston’s Table of Usual Root Progressions. The development of tonality is illustrated with the historical quotations of commentators from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, and can be characterised as follows. At the beginning of the seventeenth century multiple ‘finals’ were possible, each associated with a different interval configuration (mode). By the end of the seventeenth century, however, only two interval configurations were in regular use: those pertaining to the modern major- minor key system. The implications of this development are discussed with respect interval cycles and their hypothesised effect within music. -

A Natural System of Music

A Natural System of Music based on the Approximation of Nature by Augusto Novaro Mexico, DF 1927 Translated by M. Turner. San Francisco, 2003 Chapter I Music Music is a combination of art and science in which both complement each other in a marvelous fashion. Although it is true that a work of music performed or composed without the benefit of Art comes across as dry and expressionless, it is also true that a work of art cannot be considered as such without also satisfying the principles of science. Leaving behind for a moment the matters of harmony and the art of combining sounds, let us concentrate for the moment only on the central matter of the basis of music: The unity tone and it’s parts in vibrations, which can be divided into three groups: the physical, the mathematical and the physiological. The physical aspect describes for us how the sound is produced, the mathematical it’s numerical and geometrical relationships, the physiological being the study of the impressions that such a tone produces in our emotions.. Musical sounds are infinite. However we can break them down and classify them into seven degrees and denominations: Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti 1° 2° 3° 4° 5° 6° 7° Climbing to ‘Ti’ we reach the duplicate of ‘Do’, that is to say Do², the unity note of the previous series. Ascending in this same manner, we reach Do3, Do4, etc. We shall define the musical scale in seven steps, not because it invariably must be seven; we could also choose to use five or nine divisions, perhaps they would be more practical. -

Musical Techniques

Musical Techniques Musical Techniques Frequencies and Harmony Dominique Paret Serge Sibony First published 2017 in Great Britain and the United States by ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms and licenses issued by the CLA. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms should be sent to the publishers at the undermentioned address: ISTE Ltd John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 27-37 St George’s Road 111 River Street London SW19 4EU Hoboken, NJ 07030 UK USA www.iste.co.uk www.wiley.com © ISTE Ltd 2017 The rights of Dominique Paret and Serge Sibony to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Library of Congress Control Number: 2016960997 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78630-058-4 Contents Preface ........................................... xiii Introduction ........................................ xv Part 1. Laying the Foundations ............................ 1 Introduction to Part 1 .................................. 3 Chapter 1. Sounds, Creation and Generation of Notes ................................... 5 1.1. Physical and physiological notions of a sound .................. 5 1.1.1. Auditory apparatus ............................... 5 1.1.2. Physical concepts of a sound .......................... 7 1.1.3.