Tuning: at the Grcssroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

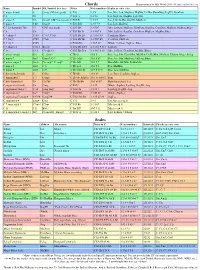

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell JAMES CLERK MAXWELL Perspectives on his Life and Work Edited by raymond flood mark mccartney and andrew whitaker 3 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries c Oxford University Press 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2013942195 ISBN 978–0–19–966437–5 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Orientalism As Represented in the Selected Piano Works by Claude Debussy

Chapter 4 ORIENTALISM AS REPRESENTED IN THE SELECTED PIANO WORKS BY CLAUDE DEBUSSY A prominent English scholar of French music, Roy Howat, claimed that, out of the many composers who were attracted by the Orient as subject matter, “Debussy is the one who made much of it his own language, even identity.”55 Debussy and Hahn, despite being in the same social circle, never pursued an amicable relationship.56 Even while keeping their distance, both composers were somewhat aware of the other’s career. Hahn, in a public statement from 1890, praised highly Debussy’s musical artistry in L'Apres- midi d'un faune.57 Debussy’s Exposure to Oriental Cultures Debussy’s first exposure to oriental art and philosophy began at Mallarmé’s Symbolist gatherings he frequented in 1887 upon his return to Paris from Rome.58 At the Universal Exposition of 1889, he had his first experience in the theater of Annam (Vietnam) and the Javanese Gamelan orchestra (Indonesia), which is said to be a catalyst 55Roy Howat, The Art of French Piano Music: Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, Chabrier (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 110 56Gavoty, 142. 57Ibid., 146. 58François Lesure and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/07353 (accessed April 4, 2011). 33 34 in his artistic direction. 59 In 1890, Debussy was acquainted with Edmond Bailly, esoteric and oriental scholar, who took part in publishing and selling some of Debussy’s music at his bookstore L’Art Indépendeant. 60 In 1902, Debussy met Louis Laloy, an ethnomusicologist and music critic who eventually became Debussy’s most trusted friend and encouraged his use of Oriental themes.61 After the Universal Exposition in 1889, Debussy had another opportunity to listen to a Gamelan orchestra 11 years later in 1900. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

Helmholtz's Dissonance Curve

Tuning and Timbre: A Perceptual Synthesis Bill Sethares IDEA: Exploit psychoacoustic studies on the perception of consonance and dissonance. The talk begins by showing how to build a device that can measure the “sensory” consonance and/or dissonance of a sound in its musical context. Such a “dissonance meter” has implications in music theory, in synthesizer design, in the con- struction of musical scales and tunings, and in the design of musical instruments. ...the legacy of Helmholtz continues... 1 Some Observations. Why do we tune our instruments the way we do? Some tunings are easier to play in than others. Some timbres work well in certain scales, but not in others. What makes a sound easy in 19-tet but hard in 10-tet? “The timbre of an instrument strongly affects what tuning and scale sound best on that instrument.” – W. Carlos 2 What are Tuning and Timbre? 196 384 589 amplitude 787 magnitude sample: 0 10000 20000 30000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 time: 0 0.23 0.45 0.68 frequency in Hz Tuning = pitch of the fundamental (in this case 196 Hz) Timbre involves (a) pattern of overtones (Helmholtz) (b) temporal features 3 Some intervals “harmonious” and others “discordant.” Why? X X X X 1.06:1 2:1 X X X X 1.89:1 3:2 X X X X 1.414:1 4:3 4 Theory #1:(Pythagoras ) Humans naturally like the sound of intervals de- fined by small integer ratios. small ratios imply short period of repetition short = simple = sweet Theory #2:(Helmholtz ) Partials of a sound that are close in frequency cause beats that are perceived as “roughness” or dissonance. -

Early Experimental and Electronic Music

Early Experimental and Electronic Music Today you will listen to early experimental and electronic music composed in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. Think about the following questions as you listen to the music. 1. One of your listening assignments, “Valse Sentimentale,” is played by Clara Rockmore, a virtuoso on the theremin, an early electronic instrument. Look at the YouTube videos of Theremin and Clara Rockmore playing the theremin. How is the instrument played? Why has it been used only infrequently as a serious musical instrument? 2. When was the theremin developed and who was its inventor? 3. As an additional listening assignment, listen to “Good Vibrations” by the Beach Boys (in the listening for Monday). Where do you hear an electro-theremin, which is similar to the theremin, but easier to play? 4. What are the connections between the theremin and modern-day synthesizers? 5. What instrument is being played in “Oriason?” From your reading, what is unusual about the use of this instrument in this recording? 6. Watch the YouTube video of Thomas Bloch playing Messian piece on the Ondes-Martenot. How does is this instrument similar to but yet different from a piano? What does it have in common with the theremin. 6. People often think that experimental music is difficult and not beautiful. Is that true of all the music in these lessons? Is it true sometimes? Give examples. 7. The well-tempered scale usually used in Western music has 12 pitches in an octave. Well-tempered scale (12 pitches in an octave) In the section on Partch in Gann’s American Music in the Twentieth Century, Partch is said to have rebelled against the “acoustic lie” of the well-tempered scale. -

Technical Analysis on HW Ernst's Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple

Technical Analysis on Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst’s Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple Voices In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music Violin by Shang Jung Lin M.M. The Boston Conservatory November 2019 Committee Chair: Won-Bin Yim, D.M.A. Abstract Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst was a Moravian violinist and composer who lived between 1814-1865. He was a friend of Brahms, collaborator with Mendelssohn, and was admired by Berlioz and Joachim. He was known as a violin virtuoso and composed many virtuosic works including an arrangement of Schubert’s Erlkönig for solo violin. The focus of this document will be on his Six Etudes for Solo Violin in Multiple Voices (also known as the Six Polyphonic Etudes). These pieces were published without opus number around 1862-1864. The etudes combine many different technical challenges with musical sensitivity. They were so difficult that the composer never gave a public performance of them. No. 6 is the most famous of the set, and has been performed by soloists in recent years. Ernst takes the difficulty level to the extreme and combines different layers of techniques within one hand. For example, the second etude has a passage that combines chords and left-hand pizzicato, and the sixth etude has a passage that combines harmonics with double stops. Etudes from other composers might contain these techniques but not simultaneously. The polyphonic nature allows for this layering of difficulties in Ernst’s Six Polyphonic Etudes. -

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya Indonesia – Karawitan) Course Code / Credits : BDU 2303/ 3 SKS Teaching Period : January-June Semester Language Instruction : Indonesian Department : Sastra Nusantara Faculty : Faculty of Arts and Humanities (FIB) Course Description The course of Indonesian Cultural Arts (Karawitan) is a compulsory course for (regular) students of Faculty of Cultural Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada, especially for the first and second semesters. The course is held every semester and is offered and can be taken by every student from semester 1 to 2. There are no prerequisites for Karawitan courses. The position of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) as the compulsory course serves to introduce the students to one aspect of Indonesian (or Javanese) art and culture and the practical knowledge related to the performance of traditional Javanese musical instruments, namely gamelan. This course also aims to provide both introduction and theoretical and practical understanding for the students of the Faculty of Cultural Science on gamelan instrument techniques, namely gendhing technique, that is found in Karawitan. Topics in this course include identification of Javanese gamelan instruments, exploration of tones in Javanese gamelan, gendhing instrument method and practice, as well as observation of traditional art performances. Proportionally, 30% of these courses contains briefing theoretical insights, 40% contains gamelan practice, and 30% contains provision of experience in a form of group collaboration and interaction Course Objectives The course of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) in general aims to provide theoretical and practical supplies through skill, application, and carefulness to recognize various instruments of Gamelan. Through this course, students are observant in identifying the various instruments of the gamelan and its application as instrumental and vocal art in karawitan. -

Interval Cycles and the Emergence of Major-Minor Tonality

Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 5, No. 3, 2010 Modes on the Move: Interval Cycles and the Emergence of Major-Minor Tonality MATTHEW WOOLHOUSE Centre for Music and Science, Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: The issue of the emergence of major-minor tonality is addressed by recourse to a novel pitch grouping process, referred to as interval cycle proximity (ICP). An interval cycle is the minimum number of (additive) iterations of an interval that are required for octave-related pitches to be re-stated, a property conjectured to be responsible for tonal attraction. It is hypothesised that the actuation of ICP in cognition, possibly in the latter part of the sixteenth century, led to a hierarchy of tonal attraction which favoured certain pitches over others, ostensibly the tonics of the modern major and minor system. An ICP model is described that calculates the level of tonal attraction between adjacent musical elements. The predictions of the model are shown to be consistent with music-theoretic accounts of common practice period tonality, including Piston’s Table of Usual Root Progressions. The development of tonality is illustrated with the historical quotations of commentators from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, and can be characterised as follows. At the beginning of the seventeenth century multiple ‘finals’ were possible, each associated with a different interval configuration (mode). By the end of the seventeenth century, however, only two interval configurations were in regular use: those pertaining to the modern major- minor key system. The implications of this development are discussed with respect interval cycles and their hypothesised effect within music. -

Surprising Connections in Extended Just Intonation Investigations and Reflections on Tonal Change

Universität der Künste Berlin Studio für Intonationsforschung und mikrotonale Komposition MA Komposition Wintersemester 2020–21 Masterarbeit Gutachter: Marc Sabat Zweitgutachterin: Ariane Jeßulat Surprising Connections in Extended Just Intonation Investigations and reflections on tonal change vorgelegt von Thomas Nicholson 369595 Zähringerstraße 29 10707 Berlin [email protected] www.thomasnicholson.ca 0172-9219-501 Berlin, den 24.1.2021 Surprising Connections in Extended Just Intonation Investigations and reflections on tonal change Thomas Nicholson Bachelor of Music in Composition and Theory, University of Victoria, 2017 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Department of Composition January 24, 2021 First Supervisor: Marc Sabat Second Supervisor: Prof Dr Ariane Jeßulat © 2021 Thomas Nicholson Universität der Künste Berlin 1 Abstract This essay documents some initial speculations regarding how harmonies (might) evolve in extended just intonation, connecting back to various practices from two perspectives that have been influential to my work. The first perspective, which is the primary investigation, concerns itself with an intervallic conception of just intonation, centring around Harry Partch’s technique of Otonalities and Utonalities interacting through Tonality Flux: close contrapuntal proximities bridging microtonal chordal structures. An analysis of Partch’s 1943 composition Dark Brother, one of his earliest compositions to use this technique extensively, is proposed, contextualised within his 43-tone “Monophonic” system and greater aesthetic interests. This is followed by further approaches to just intonation composition from the perspective of the extended harmonic series and spectral interaction in acoustic sounds. Recent works and practices from composers La Monte Young, Éliane Radigue, Ellen Fullman, and Catherine Lamb are considered, with a focus on the shifting modalities and neighbouring partials in Lamb’s string quartet divisio spiralis (2019).