Debussy Préludes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Pas Sur La Neige

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Mystères limpides: Time and Transformation in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige Debussy est mystérieux, mais il est clair. —Vladimir Jankélévitch STEVEN RINGS Introduction: Secrets and Mysteries sive religious orders). Mysteries, by contrast, are fundamentally unknowable: they are mys- Vladimir Jankélévitch begins his 1949 mono- teries for all, and for all time. Death is the graph Debussy et le mystère by drawing a dis- ultimate mystery, its essence inaccessible to tinction between the secret and the mystery. the living. Jankélévitch proposes other myster- Secrets, per Jankélévitch, are knowable, but ies as well, some of them idiosyncratic: the they are known only to some. For those not “in mysteries of destiny, anguish, pleasure, God, on the secret,” the barrier to knowledge can love, space, innocence, and—in various forms— take many forms: a secret might be enclosed in time. (The latter will be of particular interest a riddle or a puzzle; it might be hidden by acts in this article.) Unlike the exclusionary secret, of dissembling; or it may be accessible only to the mystery, shared and experienced by all of privileged initiates (Jankélévitch cites exclu- humanity, is an agent of “sympathie fraternelle et . commune humilité.”1 An abbreviated version of this article was presented as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music collo- 1Vladimir Jankélévitch, Debussy et le mystère (Neuchâtel: quium series in November 2007. I am grateful for the Baconnière, 1949), pp. 9–12 (quote, p. 10). See also his later comments I received on that occasion from students and revision and expansion of the book, Debussy et le mystère faculty. -

Liner Notes (PDF)

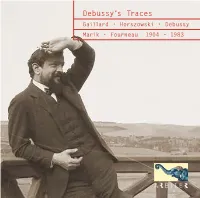

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

Orientalism As Represented in the Selected Piano Works by Claude Debussy

Chapter 4 ORIENTALISM AS REPRESENTED IN THE SELECTED PIANO WORKS BY CLAUDE DEBUSSY A prominent English scholar of French music, Roy Howat, claimed that, out of the many composers who were attracted by the Orient as subject matter, “Debussy is the one who made much of it his own language, even identity.”55 Debussy and Hahn, despite being in the same social circle, never pursued an amicable relationship.56 Even while keeping their distance, both composers were somewhat aware of the other’s career. Hahn, in a public statement from 1890, praised highly Debussy’s musical artistry in L'Apres- midi d'un faune.57 Debussy’s Exposure to Oriental Cultures Debussy’s first exposure to oriental art and philosophy began at Mallarmé’s Symbolist gatherings he frequented in 1887 upon his return to Paris from Rome.58 At the Universal Exposition of 1889, he had his first experience in the theater of Annam (Vietnam) and the Javanese Gamelan orchestra (Indonesia), which is said to be a catalyst 55Roy Howat, The Art of French Piano Music: Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, Chabrier (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 110 56Gavoty, 142. 57Ibid., 146. 58François Lesure and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/07353 (accessed April 4, 2011). 33 34 in his artistic direction. 59 In 1890, Debussy was acquainted with Edmond Bailly, esoteric and oriental scholar, who took part in publishing and selling some of Debussy’s music at his bookstore L’Art Indépendeant. 60 In 1902, Debussy met Louis Laloy, an ethnomusicologist and music critic who eventually became Debussy’s most trusted friend and encouraged his use of Oriental themes.61 After the Universal Exposition in 1889, Debussy had another opportunity to listen to a Gamelan orchestra 11 years later in 1900. -

Richard Goode, Piano

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, January 19, 2014, 3pm Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Préludes, Book I (1909–1910) Zellerbach Hall Danseuses de Delphes Voiles Le vent dans la plaine Richard Goode, piano Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir Les collines d’Anacapri Des pas sur la neige Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest PROGRAM La fille aux cheveux de lin La sérénade interrompue La Cathédrale engloutie La danse de Puck Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) From On an Overgrown Path (1901–1911) Minstrels Our Evenings A Blown-Away Leaf The program is subject to change. Come with Us! Good Night! Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837) Lebhaft Innig Mit humor Ungeduldig Einfach Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ Sehr rasch 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Nicht schnell Frisch This concert is dedicated to the memory of Donald Glaser (1926–2013). Lebhaft Balladenmäßig — Sehr rasch Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Einfach Mit Humor Wild und lustig Zart und singend Frisch Mit gutem Humor Wie aus der Ferne Nicht schnell INTERMISSION 2 3 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) birthday. “I would bind Jenůfa simply with the anguish”) and In Tears (“crying with a smile”). Linda Siegel described as vacillating between Selections from On an Overgrown Path black ribbon of the long illness, suffering and After On an Overgrown Path was published in “fits of depression with complete loss of reality laments of my daughter, Olga,” Janáček con- 1911, Janáček composed a second series of aph- and periods of seemingly placid adjustment to Composed in 1901–1902, 1908, and 1911. -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

Summergarden: Pianist Araceli Chacon to Perform

For Immediate Release July 1989 Summergarden PIANIST ARACELI CHACON TO PERFORM DEBUSSY'S PRELUDES Friday and Saturday, July 14 and 15, 7:30 p.m. A special collaboration between The Museum of Modern Art and The Juilliard School, SUMMERGARDEN 1989 presents a free series of concerts examining the music of Claude Debussy (1862-1918) and Bela Bartok (1881-1945). Under the artistic direction of Paul Zukofsky, performances are held at 7:30 p.m. on Friday and Saturday evenings in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden. The Garden is open from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m. SUMMERGARDEN is made possible by a grant from Mobil. The second SUMMERGARDEN program, on July 14 and 15, features pianist Araceli Chacon performing the following works by Claude Debussy: Preludes, Book I (1910) 1. Danseuses de Delphes 2. Voiles 3. Le Vent dans la plaine 4. Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l'air du soir 5. Les Collines d'Anacapri 6. Des Pas sur la neige 7. Ce qu'a vu le vent d'ouest 8. La Fille aux cheveux de lin 9. La Serenade interrompue 10. La Cathedrale engloutie 11. La Danse de Puck 12. Minstrels Preludes, Book II (1910-13). 13. Brouillards 14. Feuilles mortes 15. La Puerta del vino 16. Les Fees sont d'exquises danseuses - more - Friday and Saturday evenings in the Sculpture Garden of The Museum of Modern Art are made possible by a grant from Mobil 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY. 10019 5486 Tel: 212-708-9850 Cable: MODERNAkl Telex: 62370 MODART - 2 - 17. -

Richard Goode, Piano

Sunday, April 22, 2018, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Richard Goode, piano PROGRAM William Byrd (c. 1539/40 or 1543 –1623) Two Pavians and Galliardes from My Ladye Nevells Booke (1591) the seconde pavian the galliarde to the same the third pavian the galliarde to the same Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 –1750) English Suite No. 6 in D minor, BWV 811 (1715 –1720) Prelude Allemande Courante Sarabande - Double Gavotte I Gavotte II Gigue Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 –1827) Sonata No. 28 in A Major, Op. 101 (1815 –16) Etwas lebhaft, und mit der innigsten Empfindung. Allegretto, ma non troppo Lebhaft. Marschmäßig. Vivace alla Marcia Langsam und sehnsuchtsvoll. Adagio, ma non troppo, con affetto Geschwind, doch nicht zu sehr und mit Entschlossenheit. Allegro INTERMISSION Claude Debussy (1862 –1918) Préludes from Book Two (1912 –13) Brouillards—Feuilles mortes—La puerta del Vino—Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses— Bruyères—“Général Lavine” – excentric— La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune— Ondine—Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C.— Canope—Les tierces alternées—Feux d’artifice Richard Goode records for Nonesuch Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 7 PROGRAM NOTES William Byrd Among Byrd’s most significant achievements Selections from My Ladye Nevells Booke was the raising of British music for the virginal, William Byrd was not only the greatest com - the small harpsichord favored in England, to poser of Elizabethan England, but also one of a mature art, “kindling it,” according to Joseph its craftiest politicians. At a time -

Debussy Préludes Children’S Corner Paavali Jumppanen

DEBUSSY PRÉLUDES CHILDREN’S CORNER PAAVALI JUMPPANEN 1 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) CD 1 Préludes I 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes 3:46 2 II. Voiles 3:50 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine 2:15 4 IV. « Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir » 4:37 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri 3:29 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige 4:16 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest 3:40 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin 2:59 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue 2:42 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie 7:15 11 XI. La danse de Puck 2:50 12 XII. Minstrels 2:32 44:11 2 CD 2 Préludes II 1 I. Brouillards 3:17 2 II. Feuilles mortes 3:42 3 III. La puerta del Vino 3:26 4 IV. « Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses » 3:14 5 V. Bruyères 3:24 6 VI. « General Lavine » – eccentric – 2:35 7 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune 5:23 8 VIII. Ondine 3:37 9 IX. Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C. 2:37 10 X. Canope 3:50 11 XI. Les tierces alternées 2:32 12 XII. Feux d’artifice 4:49 Children’s Corner 13 I. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:20 14 II. Jimbo’s Lullaby 3:50 15 III. Serenade for the Doll 2:41 16 IV. The snow is dancing 2:48 17 V. The little Shepherd 3:31 18 VI. Golliwogg’s cake walk 3:02 60:38 PAAVALI JUMPPANEN, piano 3 CLAUDE DEBUSSY 4 Debussy’s Musical Imagery “I try to create something different–in a sense realities–and these imbeciles call it Impressionism” Claude Debussy Claude Debussy (1862–1918) cherished enigmatic statements and left behind conflicting remarks about the issue of musical imagery: on the one hand, he thought it was “more important to see a sunrise than to hear the Pastoral Symphony,” while on the other hand, as he wrote in a letter to the composer Edgar Varèse, he “liked images as much as music.” Debussy’s nuanced relationship with the worldly inspirations of his music links him with the artistic movement known as Symbolism. -

CRPH106 URBANA 66 Oec410e.105 EMS PRICE MF $O,45 HC...$11,60 340P

N080....630 ERIC REPORT RESUME ED 013 040 9..02..66 24 (REV) THE THEORY OFEXPECATION APPLIEDTO MUSICAL COLWELL, RICHARD LISTENING GFF2I3O1 UNIVERSITYOF ILLINOIS, CRPH106 URBANA 66 OEC410e.105 EMS PRICE MF $O,45 HC...$11,60 340P. *MUSIC EDUCATION, *MUSIC TECHNIQUES,*LISTENING SKILLS, *TEACHING METHODS,FIFTH GRADES LISTENING, SURVEYS, ILLINFrLS,URSAMA THE PROJECT PURPOSES WERE TO IDENTIFY THEELEMENTS IN MUSICUSED BY EXPERT LISTENERS INDETERMINING THE ARTISTIC DISCOVER WHAT VALUE OF MUSICS TO MUSICAL SKILLS ANDKNOWLEDGES ARE NECESSARY/ LISTENER TO RECOGNIZE FOR THE THESE ELEMENTS, ANDTO USE THESE CMIPARiSON WITH A FINDINGS IN A SPECIFIC AESTHETICTHEORY. ATTEMPTSWERE PACE TO DETERMINE WHETHERTHESE VALUE ELEMENTSARE TEACHABLE, LEVELS AT WHICH IF SOS THE AGE THEY ARE TEACHABLE,THE CREATION OF EVALUATE RECOGNITION MEASUREMEN7S TO OF THESE ELEMENTS,AND THE SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGES USED* THE TWO PROBLEMSSTUDIED WERE (1) THE KNOWLEDGES A STUDENT SKIMAS AND WOULD NEED TO PARTICIPATEIN THE MUSICAL EXPERIENCE AS DESCRIBEDBY MEYER S THEORY WHETHER THESE OF EXPECTATIONAND (2) PROBLEMS COULD BETAUGHT WITHIN A 2 FIFTH GRADE CHILDREN* YEAR PERIOD TO THE TOTAL LIST OFSKILLS AND KNOWLEDGES (APPROPRIATE FORMUSICAL LISTENINGAND GATHERED FROM EXPERTS) WAS OBVIOUSLY THE MUSICAL MUCH TOO EXTENSIVEAND DIFFICULT TOUTILIZE IN A ONE YEARGRADE SCHOOLCOURSE. TWENTY SEVEN WERE USED IN FIF=TH GRADE CLASSES INTERPRETING THERESULTS OF THE STUDYAND DRAW FROM THEM*APPROXIMATELY 10 PERCENTOP THE TESTSMEW THESE CLASSESWERE HIGHLYCOMMENDABLE, WITH MELODIES, CONTRASTING CADENCES, PHASESS PARTS, TIMBRE, ANDCI IMAXES ALLCORRECTLY IDENTIFIED AND MARKED.TWO VIEWPOINTS RESULTED FROM THESTUDV...(1) DESIRABILITY OF ANEARO,Y START ININTENSIVE MUSICAL THE IMPRACTICABILII"E LEARNING AND (2) OF TEACHING ADEQUATEMUSICAL SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGES WITHINTHE EXISTING ELEMENTARY MUSICFRAMEWORK BECAUSE OF LIMITED TIME ALLOWED,(GC) U. -

La Cathédrale Engloutie from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

La cathédrale engloutie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia La cathédrale engloutie (The Sunken Cathedral) is a prelude written by the French composer Claude Debussy for solo piano. It was published in 1910 as the tenth prelude in Debussy’s first of two volumes of twelve piano preludes each. It is characteristic of Debussy in its form, harmony, and content. The "organ chords" feature parallel harmony. Contents 1 Musical impressionism 2 Legend of Ys 3 Musical analysis 3.1 Form 3.2 Thematic/motivic structure 3.3 Context 3.4 Parallelism 4 Secondary Parameters 5 Arrangements 6 Notes 7 External links Musical impressionism This prelude is an example of Debussy's musical impressionism in that it is a musical depiction, or allusion, of an image or idea. Debussy quite often named his pieces with the exact image that he was composing about, like La Mer, Des pas sur la neige, or Jardins sous la pluie. In the case of the two volumes of preludes, he places the title of the piece at the end of the piece, either to allow the pianist to respond intuitively and individually to the music before finding out what Debussy intended the music to sound like, or to apply more ambiguity to the music's allusion. [1] Because this piece is based on a legend, it can be considered program music. Legend of Ys This piece is based on an ancient Breton myth in which a cathedral, submerged underwater off the coast of the Island of Ys, rises up from the sea on clear mornings when the water is transparent. -

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: a Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1 Dmitri Tymoczko The diatonic scale, considered as a subset of the twelve chromatic pitch classes, possesses some remarkable mathematical properties. It is, for example, a "deep scale," containing each of the six diatonic intervals a unique number of times; it represents a "maximally even" division of the octave into seven nearly-equal parts; it is capable of participating in a "maximally smooth" cycle of transpositions that differ only by the shift of a single pitch by a single semitone; and it has "Myhill's property," in the sense that every distinct two-note diatonic interval (e.g., a third) comes in exactly two distinct chromatic varieties (e.g., major and minor). Many theorists have used these properties to describe and even explain the role of the diatonic scale in traditional tonal music.2 Tonal music, however, is not exclusively diatonic, and the two nondiatonic minor scales possess none of the properties mentioned above. Thus, to the extent that we emphasize the mathematical uniqueness of the diatonic scale, we must downplay the musical significance of the other scales, for example by treating the melodic and harmonic minor scales merely as modifications of the natural minor. The difficulty is compounded when we consider the music of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which composers expanded their musical vocabularies to include new scales (for instance, the whole-tone and the octatonic) which again shared few of the diatonic scale's interesting characteristics. This suggests that many of the features *I would like to thank David Lewin, John Thow, and Robert Wason for their assistance in preparing this article. -

Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ Edition of French Piano Music, Part II, the Ulti- Mate Collection

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 French Piano Music, Part II The Ultimate Collection Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of French Piano Music, Part II, the Ulti- mate Collection. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “composers” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become navigation aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Contents of this CD-ROM (click on a composer/category to go to that section of the Table of Contents) DEBUSSY FAURÉ SOLO PIANO SOLO PIANO PIANO FOUR-HANDS PIANO FOUR-HANDS TWO PIANOS The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 CLAUDE DEBUSSY Pièce pour Piano (Morceau de Concours) SOLO PIANO L’isle Joyeuse (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) Masques Deux Arabesques Images, Book I Ballade I. Reflets dans l’Eau Rêverie II. Hommage à Rameau Suite Bergamasque III. Mouvement I. Prélude Children’s Corner II.