THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Speech by Ōno Genmyō, Head Priest of the Horyu-Ji Temple “Shōtoku Taishi and Horyu-Ji” (October 20, 2018, Shinjuku-Ku, Tokyo)

Speech by Ōno Genmyō, Head Priest of the Horyu-ji Temple “Shōtoku Taishi and Horyu-ji” (October 20, 2018, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo) MC Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for coming today. The town of Ikaruga, where the Horyu-ji Temple is located, is very conveniently located: just 10 minutes by JR from Nara, 20 minutes from Tennoji in Osaka, and 80 minutes from Kyoto. This historical area is home to sites that include the Horyu-ji , the Horin-ji, the Hkki-ji, the Chugu- ji, and the Fujinoki Kofun tumulus. The Reverend Mr. Ōno will be speaking with us today in detail about the Horyu-ji, which was founded in 607 by Shotoku Taishi, Prince Shotoku, a member of the imperial family. As it is home to the oldest wooden building in the world, it was the first site in Japan to be registered as a World Heritage property. However, its attractions go beyond the buildings. While Kyoto temples are famous for their gardens, Nara’s attractions are, more than anything, its Buddhist sculptures. The Horyu-ji is home to some of Japan’s most noted Buddhist statues, including the Shaka Sanzon [Shaka Triad of Buddha and Two Bosatsu], the Kudara Kannon, Yakushi Nyorai, and Kuse Kannon. Prince Shotoku was featured on the 10,000 yen bill until 1986, so there may even be people overseas who know of him. Shotoku was the creator of Japan’s first laws and bureaucratic system, a proponent of relations with China, and incorporated Buddhism into politics. Reverend Ōno, if you would be so kind. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

The Karin Ikebana Exhibition

Sairyuka - Art and ancient Asian philosophy rooted in nature KARIN-en vol.6 Sairyuka No. 35 Supplementary Karin-en News No. 6, January 2018 Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels ... The Karin Ikebana Exhibition Kanazawa / Tokyo “ Ikebana / Paintings / Vessels - The Karin Ikebana Exhibitions” were held in Kanazawa and Tokyo, co- inciding with the Hina festival and Boy’s Day celebration (Sairyuka No. 35). This page and the next show designs from the Tokyo exhibition. Sairyuka - Ikebana of the Wind Camellia (single-variant); by Karin Painting (hanging scroll) - “Sea bream”; by Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Boat-form ceramic vase and square/circular stand (thick board) Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda (ceramics), Kazuhiko Tada (stand) Koryu Association, Komagome, Tokyo 23 November Held together with the Koryu Ikebana Exhi- bition (continued on p2) Jiyuka (versatile arrangement); by Risei Morikawa Pine, camellia, eucalyptus, lily, soaproot, kori willow, other Vessel: Reika - beech, other; by Box-form ceramic vase Design by Karin Hosei Sakamoto Painting Production by Yatomi Maeda (hanging scroll) - “frog”; by Positioned at the venue entrance Karin Mounting by Akira Na- gashima Vessel: Ceramic “ kagamigata ” (parabolic) vase Design by Karin Production by Yatomi Maeda 1 The Karin Ikebana Exhibition 23 November23 Continued from page page 1 from Continued KoryuAssociation, Komagome, Sairyuka - Five Ikebana: Camellia (single tone) (From left: Wind Ikebana, Water Ikebana, Sword Ikebana, Earth Ikebana, Fire Ikebana): by Karin, Kyuuka Yamaki, Kyuuka Higashimori Paintings (hanging scroll) - From left: Enso-Wind, Enso-Water, Enso-Sword, Enso-Earth, Enso-Fire: Karin Mounting by Akira Nagashima Vessel: Square-circular ceramic vase Design by Karin Tokyo Production by Yatomi Maeda The Tokyo “Karin Ikebana Exhibition” was held on 23 【Right】 November at the Koryu Reika - (Japanese yew), other: by Association in Komagome, Ribin Okamoto alongside the established Painting (hanging scroll) - “sword”; Koryu Shoseikai Ikebana by Karin exhibition. -

Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan

Educating Minds and Hearts to Change the World A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Volume IX ∙ Number 2 June ∙ 2010 Pacific Rim Copyright 2010 The Sea Otter Islands: Geopolitics and Environment in the East Asian Fur Trade >>..............................................................Richard Ravalli 27 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Shadows of Modernity: Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan Editorial >>...............................................................Nicholas Mucks 36 Consultants Barbara K. Bundy East Timor and the Power of International Commitments in the American Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Decision Making Process >>.......................................................Christopher R. Cook 43 Editorial Board Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Syed Hussein Alatas: His Life and Critiques of the Malaysian New Economic Mark Mir Policy Noriko Nagata Stephen Roddy >>................................................................Choon-Yin Sam 55 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick Betel Nut Culture in Contemporary Taiwan >>..........................................................................Annie Liu 63 A Note from the Publisher >>..............................................Center for the Pacific Rim 69 Asia Pacific: Perspectives Asia Pacific: Perspectives is a peer-reviewed journal published at least once a year, usually in April/May. It Center for the Pacific Rim welcomes submissions from all fields of the social sciences and the humanities with relevance to the Asia Pacific 2130 Fulton St, LM280 region.* In keeping with the Jesuit traditions of the University of San Francisco, Asia Pacific: Perspectives com- San Francisco, CA mits itself to the highest standards of learning and scholarship. 94117-1080 Our task is to inform public opinion by a broad hospitality to divergent views and ideas that promote cross-cul- Tel: (415) 422-6357 Fax: (415) 422-5933 tural understanding, tolerance, and the dissemination of knowledge unreservedly. -

Japanese Buddhism. W

^be ^^cn Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE Devoted to tbc Science ot IReU^lon, tbe IReliaton ot Science, anb tbe Bitension ot tbe IReliaious parliament fbea Founded by Eowaso C. Hecklek Volume XXXIX (No. 7) JULY, 1925 (No. 830) CONTENTS PACK Frontispiece. Japanese Buddha. Japanese Buddhism. W. G. Blaikie Murdoch 385 Knowledge Interpreted as Language Behavior. Leslie A. White 396 Utopia Rediscovered. William Loftus Hare 405 The Earliest Gospel Writings as Political Documents. Wm. W. Martin .... 424 The Greek Idea of Sin. Alexander Kadison 433 Morel. B. U. Burke 436 The Organized Religion of Churches and Social Work. June P. Guild 440 The Significance of Manaism. George P. Conger 443 ^be 0pen Court tPublidbing Companig 122 S. Michigan Ave. Chicago, Illinois Per con, 20 cents (1 shiUing). Yearly, $2.00 (in tbe U.P.U^ 9i. 6d.) Entered as Second-Class Matter March 26, 1887, at the Post Office at Chlcaso, lU., under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright by The Open Codrt Publishing Company. 1924. Xlbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE ©cvote^ to the Science of IReliQion, tbe IRelfgfon of Science, and tbe Extension of tbe IReligious parliament fOea Founded by Eowako C. Hicnxk Volume XXXIX (No. 7) JULY, 1925 (No. 830) CONTENTS PACK Frontispiece. Japanese Buddha. Japanese Buddhism. W. G. Blaikie Murdoch 385 Knowledge Interpreted as Language Behavior. Leslie A. White 396 Utopia Rediscovered. William Loftus Hare 405 The Earliest Gospel Writings as Political Documents. Wm. W. Martin .... 424 The Greek Idea of Sin. Alexander Kadison 433 Morel. B. U. Burke 436 The Organized Religion of Churches and Social Work. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Myōan Eisai And

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Myōan Eisai and Conceptions of Zen Morality: The Role of Eisai's Chinese Sources in the Formation of Japanese Zen Precept Discourse A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Dermott Joseph Walsh 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Myōan Eisai and Conceptions of Zen Morality: The Role of Eisai's Chinese Sources in the Formation of Japanese Zen Precept Discourse by Dermott Joseph Walsh Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor William M. Bodiford, Chair The focus of this dissertation is Myōan Eisai, considered by scholarship as the founder of the Rinzai Zen lineage in Japan. This work aims to answer two interrelated questions: what is Eisai's Zen? and how does Eisai's Zen relate to other schools of Buddhism? Through an analysis of Eisai's texts composed following his return from his second trip to China in 1187, I illustrate the link between Eisai's understanding of Zen and the practice of morality im Buddhism; moreover this dissertation shows clearly that, for Eisai, Zen is compatible with both Tendai and the study of the precepts. This work analyzes the Eisai's use of doctrinal debates found in Chinese sources to argue for the introduction of Zen to Japan. Through this analysis, we see how Eisai views ii Zen, based on his experience in Chinese monasteries, not as a distinct group of practitioners rebelling against traditional forms of practice, but rather as a return to fundamental Buddhist positions concerning the importance of morality and its relationship to meditative practices. -

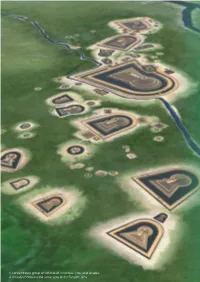

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/3-4 Placing Nichiren in the “Big Picture” Some Ongoing Issues in Scholarship Jacqueline I. Stone This article places Nichiren within the context of three larger scholarly issues: definitions of the new Buddhist movements of the Kamakura period; the reception of the Tendai discourse of original enlightenment (hongaku) among the new Buddhist movements; and new attempts, emerging in the medieval period, to locate “Japan ” in the cosmos and in history. It shows how Nicmren has been represented as either politically conservative or rad ical, marginal to the new Buddhism or its paradigmatic figv/re, depending' upon which model of “Kamakura new Buddhism” is employed. It also shows how the question of Nichiren,s appropriation of original enlighten ment thought has been influenced by models of Kamakura Buddnism emphasizing the polarity between “old” and “new,institutions and sug gests a different approach. Lastly, it surveys some aspects of Nichiren ys thinking- about “Japan ” for the light they shed on larger, emergent medieval discourses of Japan relioiocosmic significance, an issue that cuts across the “old Buddhism,,/ “new Buddhism ” divide. Keywords: Nichiren — Tendai — original enlightenment — Kamakura Buddhism — medieval Japan — shinkoku For this issue I was asked to write an overview of recent scholarship on Nichiren. A comprehensive overview would exceed the scope of one article. To provide some focus and also adumbrate the signifi cance of Nichiren studies to the broader field oi Japanese religions, I have chosen to consider Nichiren in the contexts of three larger areas of modern scholarly inquiry: “Kamakura new Buddhism,” its relation to Tendai original enlightenment thought, and new relisdocosmoloei- cal concepts of “Japan” that emerged in the medieval period. -

Shintō and Buddhism: the Japanese Homogeneous Blend

SHINTŌ AND BUDDHISM: THE JAPANESE HOMOGENEOUS BLEND BIB 590 Guided Research Project Stephen Oliver Canter Dr. Clayton Lindstam Adam Christmas Course Instructors A course paper presented to the Master of Ministry Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Ministry Trinity Baptist College February 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Stephen O. Canter All rights reserved Now therefore fear the LORD, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which your fathers served −Joshua TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... vii Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Chapter One: The History of Japanese Religion..................................................................3 The History of Shintō...............................................................................................5 The Mythical Background of Shintō The Early History of Shintō The History of Buddhism.......................................................................................21 The Founder −− Siddhartha Gautama Buddhism in China Buddhism in Korea and Japan The History of the Blending ..................................................................................32 The Sects That Were Founded after the Blend ......................................................36 Pre-War History (WWII) .......................................................................................39 -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Hiraizumi Kiyoshi (1895-1984): 'Spiritual History' in the Service of the Nation In Twentieth Century Japan By Kiyoshi Ueda A Thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, in the University of Toronto © Copyright by Kiyoshi Ueda, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44743-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44743-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

1. Revival of Reviving Sakyamuni's Buddhism and Nichiren's View on the Lotus Sutra

( 6 ) Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, Vol. 51, No. 1, December 2002 The Keynote of Nichiren's Understanding of Buddhism Hoyo WATANABE 1. Revivalof RevivingSakyamuni's Buddhism and Nichiren'sView on the Lotus Sutra Nichiren (“ú˜@,1222-1282) respected Dengyo-Daishi Saicho (“`‹³‘åŽt•Å•Ÿ, 767-822), and he tried to map out a scheme for salvation, directly linking people to Sakyamuni Buddha, with the idea of 'Integrated Buddhism' by T'ien-t'ai Ta-shih Chih-i (“V‘ä‘åŽt’qûô, 538-597). Nichiren considered the line of teachers starting form the Buddha to Chih-i and then to Saicho (the Buddha Chih-i Saicho) as the lineage which transmitted the orthodox teaching of the Buddha, and he respected them as San-goku San-shi (ŽO•‘ŽlŽt, 'Three Teachers over the Three Countries' ). Later, he arrived at a conviction that he had established a foundation for the ten-thousand years of Mappo age (the Period of Degenerated Law,–––@, Saddharma-vipralopa), as he directly inherited the teaching of the three masters. Thus, he conveyed the con- viction to his followers, by mentioning the word San-goku Shi-shi (ŽO•‘ŽlŽt, 'Four Teachers over the Three Countries'), adding his own name to the end of the previous list. Though there are 700 years of temporal gap between Chih-i and Nichiren, Ni- chiren placed Chih-i's understanding of Buddhism at the base of his thought. Viewing it from formalistic standpoint, it may indicate that Nichiren inherited Tendai-Shu (“V‘ä•@). However, having the consciousness of honoring orthodox Tendai made him consider that Chib-i and Saicho were the inheritors of the Lotus Sutra only in Zobo age (the Period of Imitative Law, ‘œ–@, Saddharmapratirupaka).