PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections Bei Dawei

4 Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections Bei Dawei Abstract Tibetan Buddhism, it is often said, discourages conversion. The Dalai Lama is one of many Buddhist leaders who have urged spiritual seekers not to convert to Tibetan Buddhism, but to remain with their own religions. And yet, despite such admonitions, conversions somehow occur—Tibetan dharma centers throughout the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and East/Southeast Asia are filled with people raised as Jews, Christians, or followers of the Chinese folk religion. It is appropriate to ask what these new converts have gained, or lost; and what Tibetan Buddhism and other religions might do to better adapt. One paradox that emerges is that Western liberals, who recoil before the fundamentalists of their original religions, have embraced similarly authoritarian, literalist values in foreign garb. This is not simply an issue of superficial cultural differences, or of misbehavior by a few individuals, but a systematic clash of ideals. As the experiences of Stephen Batchelor, June Campbell, and Tara Carreon illustrate, it does not seem possible for a viable “Reform” version of Tibetan Buddhism (along the lines of Reform Judaism, or Unitarian Universalism) ever to arise—such an egalitarian, democratic, critical ethos would tend to undermine the institution of Lamaism, without which Tibetan Buddhism would lose its raison d’être. The contrast with the Chinese folk religion is less obvious, since Tibetan Buddhism appeals to many of the same superstitious compulsions, and there is little direct disagreement. Perhaps the key difference is that Tibetan Buddhism (in common with certain institutionalized forms of Chinese Buddhism) expands through predation upon weaker forms of religious identity and praxis. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 17 2015 Special Issue: Fiftieth Anniversary of the Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Moraga, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. Romanized Chinese follows Pinyin system (except in special cases); romanized Japanese, the modified Hepburn system. Japanese/Chinese names are given surname first, omit- ting honorifics. Ideographs preferably should be restricted to notes. -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage New Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISBN 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San irst Printing, 2002 " 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 " 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety, for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma, is allowed after prior notification to the author. New Cover Design ,nset photo shows the famous Reclining .uddha image at Kusinara. ,ts uni/ue facial e0pression evokes the bliss of peace 1santisukha2 of the final liberation as the .uddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the 3reat Stupa of Sanchi located near .hopal, an important .uddhist shrine where relics of the Chief 4isciples and the Arahants of the Third .uddhist Council were discovered. Printed in ,uala -um.ur, 0alaysia 1y 5a6u6aya ,ndah Sdn. .hd., 78, 9alan 14E, Ampang New Village, 78000 Selangor 4arul Ehsan, 5alaysia. Tel: 03-42917001, 42917002, a0: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATI2N This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to ,ndia from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in .uddhism, have made those 6ourneys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

The Zen Studies Society

T H E N E W S L E T T E R O F THE ZEN STUDIES SOCIETY View of Mt. Fuji from Mt. Dai Bosatsu W I N T E R / S P R I N G 2006 Teisho on Rinzai Roku, The Book of Rinzai, Chapter 14 Eido T. Shimano Roshi 2 Dharma talk on Mumonkan, Gateless Gate Case 19 Roko ni-Osho Sherry Chayat 8 Dogyo-ninin (We Two Together) Shoshin Anne Hughes 13 Diary of Our Pilgrimage 2005 Seigan Ed Glassing 18 Dream? Fujin Zenni 25 My Impressions of the Pilgrimage to Japan Doshin David Schubert 26 Yamakawa Roshi performing Dai-Hannya View from inside the Genkan of Shogen-ji Our Trip October 2005 Yayoi Karen Matsumoto 27 Sesshin at Shogen-ji Saiun Atsumi Hara 29 Mandala Memories Banko Randy Phillips 31 Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji News 33 New York Zendo Shobo-ji News 36 Zen Studies Society News 37 Dai Bosatsu Zendo 2006 Calendar 39 New York Zendo 2006 Calendar 40 Published twice annually by The Zen Studies Society, Inc. Eido T. Shimano Roshi, Abbot Offices: New York Zendo Shobo-ji 223 East 67th Street New York, NY 10021-6087 Tel (212)861-3333 Fax 628-6968 offi[email protected] Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji 223 Beecher Lake Road Livingston Manor, NY 12758-6000 Tel (845)439-4566 Fax 439-3119 Roshi stands on top of Mount Dai Bosatsu offi[email protected] Editor: Seigan Edwin Glassing; News: Aiho-san Y. Shimano, Seigan Edwin Glassing, Fujin Zenni, Jokei Megumi Kairis; Graphic design:Banko Randy Phillips; Editorial Assistant and Proofreading: Myochi Nancy O’Hara; Teisho Transcription and Editing: Jimin Anna Klegon; Final Editing: Myochi Nancy O’Hara Photo Credits: Junsho Shelley Bello (pp. -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

WHV- Protect Swayambhu, Nepal, Volunteers Initiative Nepal

WHV – Protect Swayambhu Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Cultural property inscribed on the 17/09/2016 - 29/09/2016 World Heritage List since 1979 Located in the foothills of the Himalayas, the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage property is inscribed as seven Monument Zones. As Buddhism and Hinduism developed and changed over the centuries throughout Asia, both religions prospered in Nepal and produced a powerful artistic and architectural fusion beginning at least from the 5th century AD, but truly coming into its own in the three-hundred-year-period between 1500 and 1800 AD. These monuments were defined as the outstanding cultural traditions of the Newars, manifested in their unique urban settlements, buildings and structures with intricate ornamentation displaying outstanding craftsmanship in brick, stone, timber and bronze that are some of the most highly © TTC developed in the world. Project objectives: Swayambhu stupa and its surroundings have been dramatically damaged by the 2015 earthquake, and a first World Heritage Volunteers camp has successfully taken place in December of the same year. Following up on the work and partnerships developed, the project aims at supporting the local authorities and experts in the important reconstruction and renovation work ongoing, and at running promotional, and educational activities to further sensitize the local population and visitors about the protection of the site. Project activities: The volunteers will be directly involved in the undergoing renovation work, supporting the local experts and authorities to preserve the area and continue the reconstruction work started after the earthquake. After receiving targeted training by local experts, the participants will also run an educational campaign on the history and importance of the site and its needs and threats, aiming at reaching out to the community and in particular to the students of local universities and colleges. -

Skanda Sashti Approaching the Lord of Illumination

folio line HOLY DAYS THAT AMERICA’S HINDUS CELEBRATE s. rajam Skanda Sashti Approaching the Lord of Illumination the fi ghting rooster. Devotees pilgrimage to kanda Sashti is a six-day South Indian festival to Skanda, the Murugan’s temples, especially the temple in Lanham, Maryland, and the seaside sanctuary Lord of Religious Striving, also known as Murugan or Karttikeya. at Tiru chendur in South India. SIt begins on the day after the new moon in the month of Karttika (October/November) with chariot processions and pujas invoking His What is the legend of Skanda Sashti? protection and grace. The festival honors Skanda’s receiving His lance, It is said that eons ago, Skanda fought a power- ful asura, or demon, named Surapadman, who or vel, of spiritual illumination, and culminates in a victory celebration embodied the forces of selfi shness, ignorance, of spiritual light over darkness on the fi nal day. Penance, austerity, fast- greed and chaos. Skanda defeated and mas- tered those lower forces, which He uses, to this ing and devout worship are especially fruitful during this sacred time. sitaraman soumya day, to the greater good. The subdued demon became his faithful servant, the proud and Who is Skanda? broken, families enjoy a sweet pudding called beautiful peacock on which Skanda rides. Kesari Skanda is a God of many attributes, often payasam along with fried delicacies. A six- This quick and easy sweet semolina- depicted as six-faced and twelve-armed. part prayer for protection, called the Skanda What happens on the sixth day? based dish gets its name from kesar, or Saivite Hindus hail this supreme warrior, the Sashti Kavacham, is chanted. -

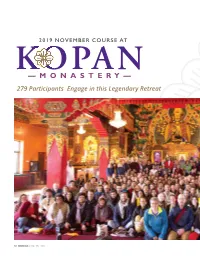

— M O N a S T E R

2019 NOVEMBER COURSE AT KOPAN —MONASTERY— 279 Participants Engage in this Legendary Retreat 52 MANDALA | Issue One 2020 Every year, the November Course, a month-long lamrim meditation course at Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, draws diverse students from around the world. What started in 1971 with a dozen students in attendance, reached a record 279 participants from forty-nine countries this year with Ven. Robina Courtin teaching the course for the first time. This was also the first course held in Kopan’s new Chenrezig gompa. Mandala editor, Carina Rumrill asked Ven. Robina about this year’s course, and we share this beautiful account of her experience and history with this style of retreat. THIS YEAR’S RECORD NUMBER OF PARTICIPANTS — 279 PEOPLE FROM FORTY-NINE COUNTRIES — WITH KOPAN’S ABBOT KHEN RINPOCHE THUBTEN CHONYI, VEN. ROBINA COURTIN, AND OTHER TEACHERS AND MEDITATION LEADERS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). Issue One 2020 | MANDALA 53 VEN. ROBINA COURTIN OFFERED A MANDALA TO RINPOCHE REQUESTING TEACHINGS. PHOTO BY VEN. THUBTEN CHOYING (SARAH BROOKS). AND THE BLESSINGS: YOU COULDN’T HELP BUT FEEL THEM BY VEN. ROBINA COURTIN The Kopan November Course is legendary. The first of what But the beauty of the place was its saving grace: a hill became an annual event, one month of lamrim teachings by surrounded on all sides by the terraced fields of the magnifi cent Lama Zopa Rinpoche to a dozen Westerners fifty years ago, Kathmandu Valley, with mountains to the north and the holy quickly became a magnet for spiritual seekers worldwide.