Kamakura Period, Early 14Th Century Japanese Cypress (Hinoki) with Pigment, Gold Powder, and Cut Gold Leaf (Kirikane) H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

View of the Study

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: March 2, 2005 I, MICHAEL DAVID FOWLER, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Piano It is entitled: Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Piano Media: Finding Parallelisms to Patterns in Japanese Culture. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: James Culley Kenneth Griffiths Frank Wienstock _______________________________ 2 Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Piano Media: Finding Parallelisms to Patterns in Japanese Culture A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS IN PIANO in the Keyboard Division, of the College Conservatory of Music 2005 by Michael D. Fowler Dip.Mus., University of Newcastle, 1994 B.Mus. (Hons), University of Newcastle, 1996 M.M. University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: James Culley 3 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the musical analysis of Toshi Ichiyanagi’s 1972 solo piano composition Piano Media, and an examination of musical processes and considerations that mirror and parallel patterns of traditional Japanese culture. Through brief studies of language construction, Zen, Pachinko and traditional aesthetics, analogies and references can be used to highlight congruent musical structures and predilections in Ichiyanagi’s work. The final goal is to define the work not only within musical terms of analysis, but also within a cultural context. 4 Copyright © 2004 by Michael Fowler All Rights Reserved 5 CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 9 Overview of the Study PART 1. SELECTED ELEMENTS OF JAPANESE CULTURE II. THE CULTIVATION OF THE JAPANESE SENSIBILITY THROUGH THE ARTS . -

The Japanese Religio-Cultural Context

CHAPTER TWO THE JAPANESE RELIGIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT Introduction This chapter introduces three factors that provide essential background information for my investigation into Endo’s theology of inculturation. First, I give a historical sketch of Japanese religion. Secondly, I look at different types of Shinto and clarify aspects of koshinto that inform contemporary Japanese culture. This is important as koshinto with its modern, psychological, and spiritual meanings is the type of Shinto that I observe in Endo’s attempts at inculturation. In connection with this I introduce the Japanese concept of the ‘divine’, and its role in the history of Shinto-Buddhist-Christian relationships. I also go on to propose that koshinto plays a fundamental role in shaping both different types of womanhood in Japan and the negative theology that forms a background to Endo’s type of inculturation. Outline of Features in Japanese Religious History Japan’s indigenous faith is Shinto, which has its roots in the age prior to 300 B.C. The animistic beliefs of this primal religion developed into a community religion with local shrines for household and guardian gods, where people worshipped the divine spirits. Gradually people began to worship ideal kami, personal kami and ancestorial kami.1 This form of Shinto is frequently called ‘proto-shinto’. Confucianism was introduced to Japan near the beginning of the 5th century as a code of moral precepts rather than a religion.2 Buddhism came to Japan from India 1 The Japanese word kami is usually translated into English by the term deity, deities, spirits, or gods. Kami in Japanese can be singular and/or plural. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

A MILLENNIAL PERSPECTIVE the World Angus Maddison Provides a Comprehensive View of the Growth and Levels of World Population Since the Year 1000

Development Centre Studies «Development Centre Studies The World Economy A MILLENNIAL PERSPECTIVE The World Angus Maddison provides a comprehensive view of the growth and levels of world population since the year 1000. In this period, world population rose 22-fold, per capita GDP 13-fold and world GDP nearly 300-fold. The biggest gains occurred in the rich countries of Economy today (Western Europe, North America, Australasia and Japan). The gap between the world leader – the United States – and the poorest region – Africa – is now 20:1. In the year 1000, the rich countries of today were poorer than Asia and Africa. A MILLENNIAL PERSPECTIVE The book has several objectives. The first is a pioneering effort to quantify the economic performance of nations over the very long term. The second is to identify the forces which explain the success of the rich countries, and explore the obstacles which hindered advance in regions which lagged behind. The third is to scrutinise the interaction between the rich and the rest to assess the degree to which this relationship was exploitative. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective is a “must” for all scholars of economics and economic history, while the casual reader will find much of fascinating interest. It is also a monumental work of reference. The book is a sequel to the author’s 1995 Monitoring the Economy: A Millennial Perspective The World World Economy: 1820-1992 and his 1998 Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, both published by the OECD Development Centre. All OECD books and periodicals are now available on line www.SourceOECD.org www.oecd.org ANGUS MADDISON This work is published under the auspices of the OECD Development Centre. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

Jomon: 11Th to 3Rd Century BCE Yayoi

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) Writing did not develop in Japan until 6th century C.E. ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Theories of origins of earliest settlers b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) “Rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements iii) Lack of social stratification? c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Simultaneous introduction of irrigation, bronze, and iron contributing to revolutionary changes (1) Impact of change in continental civilizations tend to be more gradual (2) In Japan, effect of changes are more dramatic due to its isolation (a) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements (b) Creating a distinctive synthesis in “petri-dish” (pea-tree) environment ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification (1) Objects of art—less primitive, more self-conscious (2) Late Yayoi burial practices d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Large and extravagant tombs in modern day Osaka ii) What beliefs about the afterlife do they reflect? (1) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology iii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class iv) Regional aristocracies each with its clan name (1) Uji vs. Be (2) Dramatic increase in social stratification e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) II) Yamato’s Constructions -

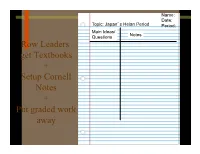

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Social Studies Curriculum

Missoula Area Curriculum Consortium Kindergarten-Grade 12 SOCIAL STUDIES CURRICULUM May 6, 2009 Alberton K-12, Bonner Elementary, Clinton Elementary, DeSmet Elementary, Drummond K-12, Florence-Carlton K-12, Frenchtown K-12, Lolo Elementary, Potomac Elementary, Seeley Lake Elementary, Sunset Elementary, Superior K-12, Swan Valley Elementary, Valley Christian K-12, Woodman Elementary TABLE OF CONTENTS MCCC 2008-2009 K-12 SOCIAL STUDIES COMMITTEE MEMBERS 1 MCCC STUDENT EXPECTATIONS 3 CURRICULUM PHILOSOPHY 3 GUIDING PRINCIPLES 4 CONTENT SCOPE AND SEQUENCE 5 SOCIAL STUDIES STANDARDS 6 NCSS CURRICULUM STANDARDS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES 6 LEARNER COMPETENCIES 8 MEETING DIVERSE STUDENT NEEDS 8 MONTANA CODE ANNOTATED-INDIAN EDUCATION FOR ALL 9 TEACHING ABOUT CONTROVERSIAL ISSUES 10 ASSESSMENT 10 GRADE/COURSE LEVEL LEARNER COMPETENCIES: Kindergarten: Learning and Working Now and Long Ago 11 Grade 1: A Child’s Place in Time and Space 15 Grade 2: People Who Make a Difference 20 Grade 3: Community and Change 23 Grade 4: Montana and Regions of the United States 28 Grade 5: United States History and Geography: Beginnings to 1850 31 Grade 6: World History and Geography: Ancient Civilizations 39 Grade 7: World History and Geography: Medieval and Early Modern Times 48 Grade 8: United States History and Geography: Constitution to WWI 59 Grade 6-8: Historical and Social Sciences Analysis Skills 71 Grades 9-12: World Geography 72 Grades 9-12: Montana: People and Issues 76 Grades 9-12: Modern World History 79 Grades 9-12: Ancient World History 87 Grade 10: Modern -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

Prospects for Changes in Gender Bias in the Japanese Language

2015 HAWAII UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCES ARTS, HUMANITIES, SOCIAL SCIENCES & EDUCATION JANUARY 03 - 06, 2015 ALA MOANA HOTEL, HONOLULU, HAWAII PROSPECTS FOR CHANGES IN GENDER BIAS IN THE JAPANESE LANGUAGE TAKEMARU, NAOKO UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WORLD LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Dr. Naoko Takemaru Department of World Languages and Cultures University of Nevada. Prospects for Changes in Gender Bias in the Japanese Language Synopsis: Although gender bias remains prevalent and deeply rooted in the Japanese language, ongoing efforts to materialize the fairer representation of genders have had a significant impact on bringing about a change for the better. This paper discusses such existing instances of gender bias in the Japanese language by themes, along with any relevant changes and reforms that have taken place or are underway. Prospects for Changes in Gender Bias in the Japanese Language Naoko Takemaru, Ph.D. Department of World Languages and Cultures University of Nevada, Las Vegas Introduction While gender bias remains prevalent and deeply rooted in the Japanese language, ongoing efforts to materialize the fairer representation of genders have had a significant impact on bringing about a change for the better. This paper discusses such existing instances of gender bias in the Japanese language by themes, along with any relevant changes and reforms that have taken place or are underway. In this paper, the Hepburn system is used for the romanization of the Japanese language. Except for proper nouns, long vowels are marked with additional vowels. Translations from Japanese are my own, unless noted otherwise. Male-Female Word Order The male-female word order is the norm of the modern Japanese kanji (ideographic characters) compounds, in which the characters representing males precede those representing females.