Matrix: a Journal for Matricultural Studies “In the Beginning, Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Investigation on the Matrilocal Residence of Smallholder Rubber Farmers in Southwest China

Marry to rubber? An investigation on the matrilocal residence of smallholder rubber farmers in southwest China X. Wang¹; S. Min¹; B. Junfei² 1: China Center for Agricultural Policy, School of Advanced Agricultural Sciences, Peking University, China, 2: China Agricultural University, College of Economics and Management, China Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper constructs a simple model of matrilocal residence with the heterogeneities in family labor and resource endowments of the wives’ households. Using the data collected from a comprehensive household survey of small-scale rubber farmers in Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture in Southwest China, the empirical results suggest that the economic factors go beyond the traditional custom of the Dai women and determine a woman's decision to be a matrilocal residence. The labor shortage of a woman’s household may foster the incidence of matrilocal residence, while a woman whose natal household possesses more rubber plantations has a higher probability of matrilocal residence. The results confirm that in the presence of labor constraint and resource heterogeneity, a higher labor demand of a household and possessing more location-specific resource may increase the likelihood of matrilocal residence of female family members after marriage. The findings complement the literature regarding matrilocal residence in a community with disequilibrium distribution of the location-specific resources. Acknowledegment: Acknowledgements: This study is conducted in the framework of the Sino-German “SURUMER Project”, funded by the Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft, Technologie und Forschung (BMBF), FKZ: 01LL0919. We also acknowledge funding supports provided by National Natural Sciences of China (71673008; 71742002). JEL Codes: J12, J17 #1128 Marry to rubber? An investigation on the matrilocal residence of smallholder rubber farmers in southwest China 1. -

Meaning of Imperial Succession Ceremonies Eiichi MIYASHIRO, Phd., the Asahi Shimbun Newspaper Senior Staff Writer

FPCJ Press Briefing May 29, 2018 Provisional Translation by FPCJ Meaning of Imperial Succession Ceremonies Eiichi MIYASHIRO, PhD., The Asahi Shimbun Newspaper Senior Staff Writer 1. What Are the Imperial Succession Ceremonies? ・The set of ceremonies involved in passing on the position of emperor to the crown prince or other imperial heir ・Not specified in any laws ・Formerly, these ceremonies were codified in the 1909 Tokyokurei [Regulations Governing Accession to the Throne], but this law was abolished. There is no mention of them in the current Imperial Household Law. ・When the current emperor was enthroned, the ceremonies were carried out based on the Tokyokurei 2. Process of Ceremonies ・There are 3 stages to the imperial succession ・First, the Senso-shiki, in which the Three Sacred Treasures are passed on as proof of imperial status ・The Sokui-shiki, in which the emperor notifies others of his accession ・The Daijosai, in which the emperor thanks the gods for bountiful harvests ・Of these, the Senso-shiki are what are now referred to as the “imperial succession ceremonies” *The Sokui-shiki are ceremonies to inform others that a new emperor has been enthroned, and not ceremonies for the enthronement itself ・For the first time, the Taiirei-Seiden-no-Gi will be performed before the imperial succession *Until now, the succession has generally been carried out after the former emperor passes away. This will be the first time in modern Japanese history that an emperor has abdicated. 3. What Ceremonies Are There? ・Four ceremonies are carried out for the imperial succession ・Kenji-to-Shokei-no-Gi, Koreiden-Shinden-ni-Kijitsu-Hokoku-no-Gi, Kashikodokoro-no-Gi, and Sokui-go-Choken-no-Gi ・In the Kenji-to-Shokei-no-Gi, two of the Three Sacred Treasures that are proof of imperial authority are passed on from the former emperor, the sword Amenomurakumo-no- Tsurugi and the jewel Yasakani-no-Magatama. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Shahooct.Pdf

October 2005 VOLUME III ISSUE 10 a place where ancient traditions thrive Hawaii Kotohira Jinsha Hawaii Dazaifu Tenmangu Autumn Thanksgiving Festival 秋季感謝大祭 The point of Thanksgiving is to remember the things we have to be grateful for. It's our special time to give thanks... not just for the food we partake, but for the thousands of fortunate moments, the multitude of blessings that we receive every day of our lives. Giving thanks is a powerful tool that can dramatically improve your life and the lives of those around you. The Autumn Thanksgiving Festival is a special day to express gratitude that will enhance every aspect of our lives. The festival commenced at 3:00 pm on Sunday, October 23, officiated by Rev. Masa Takizawa and assisted by members of the Honolulu Shinto Renmei: Rev. Naoya Shimura of Hawaii Ishizuchi Jinja, Rev. Daiya Amano of Izumo Taishakyo Mission of Hawaii and Rev. Akihiro Okada of Daijingu Temple of Hawaii. A Miko mai entitled Toyosaka no Mai was performed by Shawna Arakaki. Kyodan President Shinken Naitoh welcomed guests and invited all to join members for a time of fellowship. A delectable array of Japanese delicacies were prepared by Fujinkai President Miyono Shimoda, Vice-President Kumiko Sakai and the ladies of the women’s auxiliary club. Adding to the enjoyment was classical Japanese dances by the students of Hanayagi Mitsuyuri of Hanayagi Dancing Academy, students of Harry Urata of Urata Music Studio, hula by Lillian Yajima of the Japanese Women’s Society, Shigin by Kumiko Sakai and Hatsuko Nakazato, karaoke by Shawna Arakaki and an extraordinary rendition of Yasuki Bushi by Vice President, Robert Shimoda. -

Jomon: 11Th to 3Rd Century BCE Yayoi

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) Writing did not develop in Japan until 6th century C.E. ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Theories of origins of earliest settlers b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) “Rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements iii) Lack of social stratification? c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Simultaneous introduction of irrigation, bronze, and iron contributing to revolutionary changes (1) Impact of change in continental civilizations tend to be more gradual (2) In Japan, effect of changes are more dramatic due to its isolation (a) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements (b) Creating a distinctive synthesis in “petri-dish” (pea-tree) environment ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification (1) Objects of art—less primitive, more self-conscious (2) Late Yayoi burial practices d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Large and extravagant tombs in modern day Osaka ii) What beliefs about the afterlife do they reflect? (1) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology iii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class iv) Regional aristocracies each with its clan name (1) Uji vs. Be (2) Dramatic increase in social stratification e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) II) Yamato’s Constructions -

Gender, the Status of Women, and Family Structure in Malaysia

Malaysian Journal of EconomicGender, Studies the Status 53(1): of Women,33 - 50, 2016 and Family Structure in Malaysia ISSN 1511-4554 Gender, the Status of Women, and Family Structure in Malaysia Charles Hirschman* University of Washington, Seattle Abstract: This paper addresses the question of whether the relatively high status of women in pre-colonial South-east Asia is still evident among Malay women in twentieth century Peninsular Malaysia. Compared to patterns in East and South Asia, Malay family structure does not follow the typical patriarchal patterns of patrilineal descent, patrilocal residence of newly married couples, and preference for male children. Empirical research, including ethnographic studies of gender roles in rural villages and demographic surveys, shows that women were often economically active in agricultural production and trade, and that men occasionally participated in domestic roles. These findings do not mean a complete absence of patriarchy, but there is evidence of continuity of some aspects of the historical pattern of relative gender equality. The future of gender equality in Malaysia may depend as much on understanding its past as well as drawing lessons from abroad. Keywords: Family, gender, marriage, patriarchy, women JEL classification: I3, J12, J16, N35 1. Introduction In the introduction to her book onWomen, Politics, and Change, Lenore Manderson (1980) said that the inspiration for her study was the comment by a British journalist that the participation of Malay women in rallies, demonstrations, and the nationalist movement during the late 1940s was the most remarkable feature of post-World War II Malayan politics. The British journalist described the role of Malay women in the nationalist movement as “challenging, dominant, and vehement in their emergence from meek, quiet roles in the kampongs, rice fields, the kitchens, and nurseries” (Miller, 1982, p. -

Matrifocality and Women's Power on the Miskito Coast1

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast by Laura Hobson Herlihy 2008 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Herlihy, Laura. (2008) “Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast.” Ethnology 46(2): 133-150. Published version: http://ethnology.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/Ethnology/index Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. MATRIFOCALITY AND WOMEN'S POWER ON THE MISKITO COAST1 Laura Hobson Herlihy University of Kansas Miskitu women in the village of Kuri (northeastern Honduras) live in matrilocal groups, while men work as deep-water lobster divers. Data reveal that with the long-term presence of the international lobster economy, Kuri has become increasingly matrilocal, matrifocal, and matrilineal. Female-centered social practices in Kuri represent broader patterns in Middle America caused by indigenous men's participation in the global economy. Indigenous women now play heightened roles in preserving cultural, linguistic, and social identities. (Gender, power, kinship, Miskitu women, Honduras) Along the Miskito Coast of northeastern Honduras, indigenous Miskitu men have participated in both subsistence-based and outside economies since the colonial era. For almost 200 years, international companies hired Miskitu men as wage- laborers in "boom and bust" extractive economies, including gold, bananas, and mahogany. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

Amaterasu - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

אמאטרסו أماتيراسو آماتراسو Amaterasu - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amaterasu Amaterasu From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Amaterasu (天照 ), Amaterasu- ōmikami (天照大 神/天照大御神 ) or Ōhirume-no-muchi-no-kami (大日孁貴神 ) is a part of the Japanese myth cycle and also a major deity of the Shinto religion. She is the goddess of the sun, but also of the universe. The name Amaterasu derived from Amateru meaning "shining in heaven." The meaning of her whole name, Amaterasu- ōmikami, is "the great august kami (god) who shines in the heaven". [N 1] Based on the mythological stories in Kojiki and Nihon Shoki , The Sun goddess emerging out of a cave, bringing sunlight the Emperors of Japan are considered to be direct back to the universe descendants of Amaterasu. Look up amaterasu in Wiktionary, the free Contents dictionary. 1 History 2 Worship 3 In popular culture 4 See also 5 Notes 6 References History The oldest tales of Amaterasu come from the ca. 680 AD Kojiki and ca. 720 AD Nihon Shoki , the oldest records of Japanese history. In Japanese mythology, Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, is the sister of Susanoo, the god of storms and the sea, and of Tsukuyomi, the god of the moon. It was written that Amaterasu had painted the landscape with her siblings to create ancient Japan. All three were born from Izanagi, when he was purifying himself after entering Yomi, the underworld, after failing to save Izanami. Amaterasu was born when Izanagi washed out his left eye, Tsukuyomi was born from the washing of the right eye, and Susanoo from the washing of the nose. -

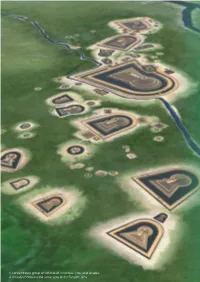

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures.