Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Contemporary Japanese Ceramics

Free admission harn.ufl.edu 3259 Hull Road Gainesville, FL 32611 Front: Hoshino Kayoko, Yakishime ginsai bachi (Unglazed bowl with silver glaze) (detail), 2009, on loan from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz Back: Yagi Kazuo, Kakiotoshi hoko (Square vessel with etched patterning) (detail), 1966, on loan from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz The Harn Museum would like to thank Joan Mirviss for her editorial assistance with this guide. Into the Fold: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics from the Horvitz Collection and this guide are generously supported by the Jeffrey Horvitz Foundation. Photos by Randy Batista. About the Author Tomoko Nagakura is a curator and professor of Japanese art. She is currently a Research Fellow for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and has worked on the Jeffrey and Carol Horvitz Collection of contemporary Japanese ceramics since 2012. Previously, she has been a curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, as well as other art institutions in Japan. Understanding Contemporary Koike Shōko, Shiro no Shell Japanese Ceramics (White Shell) (detail), 2013, on loan from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz Tomoko Nagakura Into the Fold: Contemporary Japanese Living National Treasures Female Artists At historically important kiln sites such The increased influence of women artists is another Ceramics from the Horvitz Collection as Shigaraki, Seto (in Aichi Prefecture), important dimension in the development of ceramic art Mino (in Gifu Prefecture), and Bizen in postwar Japan. After the war, secondary education October 7, 2014 – July 15, 2016 (in Okayama Prefecture), artists from was open to a wider population. -

Ishikawa Access Map Kanazawa City Center

Golf Courses KANAZAWA CITY CENTER MAP A great number of scenic golf courses exist in Ishikawa, taking advantage of the many magnificent natural landscapes. Imagine golfing on top of a hill in Noto with shots seemingly descending down to the Sea of Japan, or at the foot of Mt. Hakusan where golfers dauntlessly shoot towars the massive mountainous background. Ishikawa of- 15 16 fers you a unique opportunity to not just play golf, but be one with nature as well! HEGURAJIMA Island The Country Club Noto Kanazawa Links Golf Club ❶● ⓭● 17 14 0768-52-3131 076-237-2222 http://www.cc-noto.co.jp/ Hotel Kanazawa ⓮● Kanazawa 6 ❷● Notojima Golf and Central Country Club 18 Asanogawa Country Club 076-251-0011 River Wajima 0767-85-2311 Kanazawa Kobo-Nagaya Senmaida Rice http://www.notojima-golf.jp/ ● Hakusan Country Club Hyakuban-gai 0761-51-4181 Shopping Mall Terrece http://www.incl.ne.jp/golf/haku/haku1.html ❸● Tokinodai Country Club 13 Suzuyaki Museum 0767-27-1121 4 of Art http://www.tokinodai.co.jp/ ● Kaga Huyo Country Club Wajima 0761-65-2020 2 12 Onsen ❹● Wakura Golf Club 3 0767-52-2580 ● Twin Fields Golf Club 2 Suzu 0761-47-4500 7 Mitsuke-jima http://www.wakuragolfclub.co.jp/ 1 5 Onsen http://www.twin-fields.com/ Hotel Nikko 19 Island ❺● Noto Golf Club Ishikawa Wajima Urushi 0767-32-1212 ● Komatsu Country Club ANA Crowne Plaza Hotel Museum of Art http://www.daiwaresort.co.jp/noto-gc/ 0761-43-3030 5 NANATSUJIMA ❻● Chirihama Country Club ● Komatsu Public Golf Course Island 0767-28-4411 0761-65-2277 10 ❼● Noto Country Club ● Kaga Country Club 0767-28-3155 -

Dept of History Draft Syllabus (Cbcs)

RAJA NARENDRALAL KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) DEPT OF HISTORY DRAFT SYLLABUS (CBCS) I SEMESTER Course Course Title Credit Marks Total Th IM AM CC1T Greek and Roman Historians 6 60 10 5 75 CC2T Early Historic India 6 60 10 5 75 GE1T History of India From the earliest 6 60 10 5 75 times to C 300 BCE DSC History of India-I (Ancient India) 6 60 10 5 75 CC-1: Greek and Roman Historians C1T: Greek and Roman Historians Unit-I Module I New form of inquiry (historia) in Greece in the sixth century BCE 1.1 Logographers in ancient Greece. 1.2 Hecataeus of Miletus, the most important predecessor of Heredotus 1.3 Charon of Lampsacus 1.4 Xanthus of Lydia Module II Herodotus and his Histories 2.1 A traveller’s romance? 2.2 Herodotus’ method of history writing – his catholic inclusiveness 2.3 Herodotus’ originality as a historian – focus on the struggle between the East and the West Module III Thucydides: the founder of scientific history writing 3.1 A historiography on Thucydides 3.2 History of the Peloponnesian War - a product of rigorous inquiry and examination 3.3 Thucydides’ interpretive ability – his ideas of morality, Athenian imperialism, culture and democratic institutions 3.4 Description of plague in a symbolic way – assessment of the demagogues 3.5 A comparative study of the two greatest Greek historians Module IV Next generation of Greek historians 4.1 Xenophon and his History of Greece (Hellenica) 4.2 a description of events 410 BCE – 362 BCE 4.3 writing in the style of a high-class journalist – lack of analytical skill 4.5 Polybius and the “pragmatic” history 4.3 Diodorus Siculus and his Library of History – the Stoic doctrine of the brotherhood of man Unit II Roman Historiography Module I Development of Roman historiographical tradition 1.1 Quintus Fabius Pictor of late third century BCE and the “Graeci annals” – Rome’s early history in Greek. -

The Technological Imaginary of Imperial Japan, 1931-1945

THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron Stephen Moore August 2006 © 2006 Aaron Stephen Moore THE TECHNOLOGICAL IMAGINARY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1931-1945 Aaron Stephen Moore, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 “Technology” has often served as a signifier of development, progress, and innovation in the narrative of Japan’s transformation into an economic superpower. Few histories, however, treat technology as a system of power and mobilization. This dissertation examines an important shift in the discourse of technology in wartime Japan (1931-1945), a period usually viewed as anti-modern and anachronistic. I analyze how technology meant more than advanced machinery and infrastructure but included a subjective, ethical, and visionary element as well. For many elites, technology embodied certain ways of creative thinking, acting or being, as well as values of rationality, cooperation, and efficiency or visions of a society without ethnic or class conflict. By examining the thought and activities of the bureaucrat, Môri Hideoto, and the critic, Aikawa Haruki, I demonstrate that technology signified a wider system of social, cultural, and political mechanisms that incorporated the practical-political energies of the people for the construction of a “New Order in East Asia.” Therefore, my dissertation is more broadly about how power operated ideologically under Japanese fascism in ways other than outright violence and repression that resonate with post-war “democratic” Japan and many modern capitalist societies as well. This more subjective, immaterial sense of technology revealed a fundamental ambiguity at the heart of technology. -

Sartorius Thesis.Pdf (5.388Mb)

Material Memoir Master’s In Fine Arts Thesis Document Andrew Sartorius SUNY New Paltz Spring 2019 Material Memoir: Artist Statement My family owns a fifty acre plot of rolling red clay hills in West Virginia. When I return home, I dig clay, a pilgrimage to harvest from the strata of memory. This body of work explores the potential of wild West Virginia clay through the wood firing process. The kiln creates a dramatic range of effects as varying amounts of ash and heat amalgamate and give vitality to the wild clays I use. The kiln is my collaborator, a trusted but pleasantly unpredictable partner lending its voice to mine to create something made from a life of memory and memorial. Abstract Almost every Sunday of my childhood, my family gathered here for Sunday dinner. My family would meet on a rolling red clay hill topped with pin oak and pine forests, gentle fields, and barns that lean and sag with the weathering of time. My great grandmother lived on one side of the hill, and my grandparents on the other. My great grandmother’s parents started the tradition, and it followed the generations down to my grandmother and grandfather, Alice and Bernard Bosley, who took up the mantle during my childhood. In 2010, I moved to Japan to teach English at a rural high school in Kochi Prefecture. I returned to America in 2014 as a potter’s apprentice studying the traditional Japanese wood-fired ceramics with the ceramic artist Jeff Shapiro in Accord, New York. Since then, my grandparents have passed, but I find that they are more present in my thoughts than ever before. -

Okakura Kakuzō's Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters

Asian Review of World Histories 2:1 (January 2014), 17-45 © 2014 The Asian Association of World Historians doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2014.2.1.017 Okakura Kakuzō’s Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters, Hegelian Dialectics and Darwinian Evolution Masako N. RACEL Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, United States [email protected] Abstract Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913), the founder of the Japan Art Institute, is best known for his proclamation, “Asia is One.” This phrase in his book, The Ideals of the East, and his connections to Bengali revolutionaries resulted in Okakura being remembered as one of Japan’s foremost Pan-Asianists. He did not, how- ever, write The Ideals of the East as political propaganda to justify Japanese aggression; he wrote it for Westerners as an exposition of Japan’s aesthetic heritage. In fact, he devoted much of his life to the preservation and promotion of Japan’s artistic heritage, giving lectures to both Japanese and Western audi- ences. This did not necessarily mean that he rejected Western philosophy and theories. A close examination of his views of both Eastern and Western art and history reveals that he was greatly influenced by Hegel’s notion of dialectics and the evolutionary theories proposed by Darwin and Spencer. Okakura viewed cross-cultural encounters to be a catalyst for change and saw his own time as a critical point where Eastern and Western history was colliding, caus- ing the evolution of both artistic cultures. Key words Okakura Kakuzō, Okakura Tenshin, Hegel, Darwin, cross-cultural encounters, Meiji Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:32:22PM via free access 18 | ASIAN REVIEW OF WORLD HISTORIES 2:1 (JANUARY 2014) In 1902, a man dressed in an exotic cloak and hood was seen travel- ing in India. -

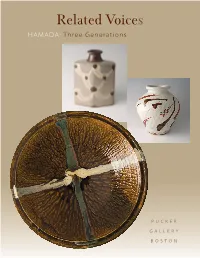

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Shinto, Primal Religion and International Identity

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 1, No. 1 (April 1996) Shinto, primal religion and international identity Michael Pye, Marburg eMail: [email protected] National identity and religious diversity in Japan Questions of social and political identity in Japan have almost always been accompanied by perceptions and decisions about religion. This is true with respect both to internal political issues and to the relations between Japan and the wider world. Most commonly these questions have been linked to the changing roles and fortunes of Shinto, the leading indigenous religion of Japan. Central though Shinto is however, it is important to realize that the overall religious situation is more complex and has been so for many centuries. This paper examines some of these complexities. It argues that recent decades in particular have seen the clear emergence of a more general "primal religion" in Japan, leaving Shinto in the position of being one specific religion among others. On the basis of this analysis some of the options for the Shinto religion in an age of internationalization are considered. The complexity of the relations between religion and identity can be documented ever since the Japanese reception of Chinese culture, which led to the self-definition of Shinto as the indigenous religion of Japan. The relationship is evident in the use of two Chinese characters to form the very word Shinto (shen-dao), which was otherwise known, using Japanese vocabulary, as kannagara no michi (the way in accordance with the kami).1 There are of course some grounds for arguing, apparently straightforwardly, that Shinto is the religion of the Japanese people. -

HEART & MATTER: FERMENTATION in a TIME of CRISIS Aaron C

HEART & MATTER: FERMENTATION IN A TIME OF CRISIS Aaron C. Delgaty A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Christopher T. Nelson Margaret J. Wiener Peter Redfield Townsend Middleton Brad Weiss © 2020 Aaron C. Delgaty ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron C. Delgaty: Heart & Matter: Fermentation in a Time of Crisis (Under the direction of Christopher T. Nelson) In Heart & Matter, I explore contemporary artisan movements from the perspectives of the artisans that animate these movements, considering how people draw on this emergent category of alternate labor and identity to navigate crises of social, economic, and personal precariousness within the artisan industry. Moving from North Carolina to Okinawa, Tokyo to Chicago, my collaborators shared the quotidian anxiety of how to keep their crafts - and the businesses, livelihoods, and identities tied up in those crafts – relevant, viable, and even successful. Toward survival, my interlocutors engaged in practices of resilience, innovation, and collaboration, elemental threads that wove their working philosophies of craft. At the visceral intersection of ethnography and apprenticeship, I trace a working ethos of emergent artisanship that captures the hopes and anxieties, the successes and failures, the everyday lives and works of craftspeople confronting uncertain frontiers of vocation and taste. By way of introduction, Every Scar a Lesson outlines and demonstrates my primary methodology, an itinerant series of participant observations from the perspective of formal and informal apprenticeship, or what I call a wandering apprenticeship. -

Medium Specificity and Materiality

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2015 THESIS Dirty Tricks The relevance of skill, expression and authenticity in contemporary clay-based art by Trevor Fry December 2015 STATEMENT This volume is presented as a record of the work undertaken for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF FIGURES .......................................................................................... v SUMMARY.......................................................................................................... ix INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1. THE MAGIC OF CLAY .................................................................................. 9 1.1 Phenomenology and post-structuralism, Edmund de Waal and Rosalind Krauss .......... 19 1.2 De Waal and the magic of clay ........................................................................................ 20 1.3 The deskilled present ....................................................................................................... 30 1.3.1 Urs Fischer’s lumpy spectacles ................................................................................ 33 1.4 Rosalind Krauss ............................................................................................................... 42 1.4.1 Medium specificity .................................................................................................... -

Japan in the Meiji

en Japan in the Meiji Era The collection of Heinrich von Siebold Galleries of Marvel Japan in the Meiji Era Japan in the Meiji Era The collection of The collection of Heinrich von Siebold Heinrich von Siebold This exhibition grew out of a research Meiji period (1868–1912) as a youth. Through project of the Weltmuseum Wien in the mediation of his elder brother Alexan- co-operation with the research team of der (1846–1911), he obtained a position as the National Museum of Japanese History, interpreter to the Austro-Hungarian Diplo- Sakura, Japan. It is an attempt at a reap- matic Mission in Tokyo and lived in Japan praisal of nineteenth-century collections for most of his life, where he amassed a of Japanese artefacts situated outside of collection of more than 20,000 artefacts. He Japan. The focus of this research lies on donated about 5,000 cultural objects and Heinrich von Siebold (1852–1908), son of art works to Kaiser Franz Joseph in 1889. the physician and author of numeral books About 90 per cent of the items pictured in Hochparterre on Japan Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796– the photographs in the exhibition belong to 1866). Heinrich went to Japan during the the Weltmuseum Wien. Room 1 Ceramics and agricultural implements Room 2 Weapons and ornate lacquer boxes Room 3 Musical instruments and bronze vessels Ceramics and Room 1 agricultural implements 1 The photographs show a presentation of artefacts of the Ainu from Hokkaido, togeth- This large jar with a lid is Kutani ware from dynasty (1638–1644) Jingdezhen kilns, part of Heinrich von Siebold’s collection from er with agricultural and fishing implements Ishikawa prefecture.