The Semantics of Word Formation and Lexicalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handling Word Formation in Comparative Linguistics

Developing an annotation framework for word formation processes in comparative linguistics Nathanael E. Schweikhard, MPI-SHH, Jena Johann-Mattis List, MPI-SHH, Jena Word formation plays a central role in human language. Yet computational approaches to historical linguistics often pay little attention to it. This means that the detailed findings of classical historical linguistics are often only used in qualitative studies, yet not in quantitative studies. Based on human- and machine-readable formats suggested by the CLDF-initiative, we propose a framework for the annotation of cross-linguistic etymological relations that allows for the differentiation between etymologies that involve only regular sound change and those that involve linear and non-linear processes of word formation. This paper introduces this approach by means of sample datasets and a small Python library to facilitate annotation. Keywords: language comparison, cognacy, morphology, word formation, computer-assisted approaches 1 Introduction That larger levels of organization are formed as a result of the composition of lower levels is one of the key features of languages. Some scholars even assume that compositionality in the form of recursion is what differentiates human languages from communication systems of other species (Hauser et al. 2002). Whether one believes in recursion as an identifying criterion for human language or not (see Mukai 2019: 35), it is beyond question that we owe a large part of the productivity of human language to the fact that words are usually composed of other words (List et al. 2016a: 7f), as is reflected also in the numerous words in the lexicon of human languages. While compositionality in the sphere of semantics (see for example Barsalou 2017) is still less well understood, compositionality at the level of the linguistic form is in most cases rather straightforward. -

Greek Grammar in Greek

Greek Grammar in Greek William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Sometimes it would be nice to discuss grammar without having to drop back to our native language, so I’ve made a collection of Greek grammatical vocabulary. My primary source is E. Dickey’s Ancient Greek Scholarship. Over more than a millennium of literary scholarship in the ancient world has resulted in a vast and somewhat redundant vocabulary for many corners of grammar. Since my goal is to make it possible to produce Greek rather than to provide a guide to ancient scholarship — for which Dickey’s book is the best guide — I have left out a lot of duplicate terminology. In general I tried to pick the word that appears to inspire the Latin, and thus the modern, grammatical vocabulary. I also occasionally checked to see what Modern Greek uses for a term. Parts of Speech The Greeks divided up the parts of speech a little differently, but for the most part we’ve inherited their division. • μέρος λόγου “part of speech” • ὄνομα, τό “noun” • ἐπίθετον “adjective” (in ancient grammar considered a kind of noun) • ῥῆμα, τό “verb” • μετοχή, ἡ “participle” (which we now think of as part of the verb) • ἄρθρον, τό “article” and also relative pronoun in the scholia • ἀντωνυμία, ἡ “pronoun” { ἀναφορική “relative” { δεικτική “demonstrative” { κτητική “possessive,” i.e., ἐμός, σός, κτλ. • πρόθεσις, ἡ “preposition” ∗This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. 1 • ἐπίρρημα, τό “adverb” but also covering some particles in the scholia • σύνδεσμος, ὁ “conjunction” but, again, also covering some particles in the scholia There was no classical word that matched the contemporary notion of a particle, which were described by their function as either σύνδεσμοι or ἐπιρρήματα. -

Word Formation Models and Semantic Features of Derived Words in Orhon Inscriptions (Derivations of Nouns and Adjectives)

TRAMES, 2015, 19(69/64), 2, 171–188 WORD FORMATION MODELS AND SEMANTIC FEATURES OF DERIVED WORDS IN ORHON INSCRIPTIONS (DERIVATIONS OF NOUNS AND ADJECTIVES). A. K. Kupayeva L. N. Gumilyev Eurasian National University, Astana, Kazakhstan Abstract. In modern Turkological studies, the scientific interest in word formation arises not only from the need to study the ways of forming new words and enriching the vocabulary stock. The interest also comes from the fact that the word-formation process is often closely connected with grammatical structures and linguistic phenomena, which leads to new word formation. This work is devoted to studying the problems connected with word formation set in the language of Orhon Old Turkic inscriptions that recorded the language. These inscriptions are valuable written data about all aspects of studies of Turkology such as linguistics, history, culture etc. Furthermore, this paper considers suf- fixation and compounding as the main productive ways of word formation of language of Orhon inscriptions and gives semantic interpretation of noun and adjective derivatives. The author offers word-formation, morphemic and etymological analysis of structure of words, grouped according to word formation models. At the same time, data is given about modern Turkic languages, revealing unique features of word formation in the language of Orhon inscriptions. This data describes the phonological and semantic changes in word forming morphemes. Key words: Orhon Inscriptions, word formation models, semantic analysis, suffixation, compounding, word formation meaning DOI: 10.3176/tr.2015.2.05 1. Introduction Recently, the language of one of the oldest Turkic written records, dating back to the 7th–9th centuries, the Orhon Old Turkic, has been studied from different aspects. -

Morphological Integration of Urdu Loan Words in Pakistani English

English Language Teaching; Vol. 13, No. 5; 2020 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Morphological Integration of Urdu Loan Words in Pakistani English Tania Ali Khan1 1Minhaj University/Department of English Language & Literature Lahore, Pakistan Correspondence: Tania Ali Khan, Minhaj University/Department of English Language & Literature Lahore, Pakistan Received: March 19, 2020 Accepted: April 18, 2020 Online Published: April 21, 2020 doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n5p49 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n5p49 Abstract Pakistani English is a variety of English language concerning Sentence structure, Morphology, Phonology, Spelling, and Vocabulary. The one semantic element, which makes the investigation of Pakistani English additionally fascinating is the Vocabulary. Pakistani English uses many loan words from Urdu language and other local dialects, which have become an integral part of Pakistani English, and the speakers don't feel odd while using these words. Numerous studies are conducted on Pakistani English Vocabulary, yet a couple manage to deal with morphology. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the morphological integration of Urdu loan words in Pakistani English. Another purpose of the study is to investigate the main reasons of this morphological integration process. The Qualitative research method is used in this study. Researcher prepares a sample list of 50 loan words for the analysis. These words are randomly chosen from the newspaper “The Dawn” since it is the most dispersed English language newspaper in Pakistan. Some words are selected from the Books and Novellas of Pakistani English fiction authors, and concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edition. -

BORE ASPECTS OP MODERN GREEK SYLTAX by Athanaaios Kakouriotis a Thesis Submitted Fox 1 the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Of

BORE ASPECTS OP MODERN GREEK SYLTAX by Athanaaios Kakouriotis A thesis submitted fox1 the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1979 ProQuest Number: 10731354 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731354 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 II Abstract The present thesis aims to describe some aspects of Mod Greek syntax.It contains an introduction and five chapters. The introduction states the purpose for writing this thesis and points out the fact that it is a data-oriented rather, chan a theory-^oriented work. Chapter one deals with the word order in Mod Greek. The main conclusion drawn from this chapter is that, given the re latively rich system of inflexions of Mod Greek,there is a freedom of word order in this language;an attempt is made to account for this phenomenon in terms of the thematic structure. of the sentence and PSP theory. The second chapter examines the clitics;special attention is paid to clitic objects and some problems concerning their syntactic relations .to the rest of the sentence are pointed out;the chapter ends with the tentative suggestion that cli tics might be taken care of by the morphologichi component of the grammar• Chapter three deals with complementation;this a vast area of study and-for this reason the analysis is confined to 'oti1, 'na* and'pu' complement clauses; Object Raising, Verb Raising and Extraposition are also discussed in this chapter. -

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns

Chapter 1 Lexicalization Patterns 1 INTRODUCTION This study addresses the systematic relations in language between mean- ing and surface expression.1 (The word ``surface'' throughout this chapter simply indicates overt linguistic forms, not any derivational theory.) Our approach to this has several aspects. First, we assume we can isolate ele- ments separately within the domain of meaning and within the domain of surface expression. These are semantic elements like `Motion', `Path', `Figure', `Ground', `Manner', and `Cause', and surface elements like verb, adposition, subordinate clause, and what we will characterize as satellite. Second, we examine which semantic elements are expressed by which surface elements. This relationship is largely not one-to-one. A combina- tion of semantic elements can be expressed by a single surface element, or a single semantic element by a combination of surface elements. Or again, semantic elements of di¨erent types can be expressed by the same type of surface element, as well as the same type by several di¨erent ones. We ®nd here a range of universal principles and typological patterns as well as forms of diachronic category shift or maintenance across the typological patterns. We do not look at every case of semantic-to-surface association, but only at ones that constitute a pervasive pattern, either within a language or across languages. Our particular concern is to understand how such patterns compare across languages. That is, for a particular semantic domain, we ask if languages exhibit a wide variety of patterns, a com- paratively small number of patterns (a typology), or a single pattern (a universal). -

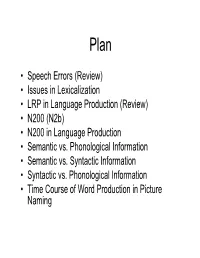

• Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic Vs

Plan • Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic vs. Phonological Information • Semantic vs. Syntactic Information • Syntactic vs. Phonological Information • Time Course of Word Production in Picture Naming Eech Sperrors • What can we learn from these things? • Anticipation Errors – a reading list Æ a leading list • Exchange Errors – fill the pool Æ fool the pill • Phonological, lexical, syntactic • Speech is planned in advance – Distance of exchange, anticipation errors suggestive of how far in advance we “plan” Word Substitutions & Word Blends • Semantic Substitutions • Lexicon is organized – That’s a horse of another color semantically AND Æ …a horse of another race phonologically • Phonological Substitutions • Word selection must happen – White Anglo-Saxon Protestant after the grammatical class of Æ …prostitute the target has been • Semantic Blends determined – Edited/annotated Æ editated – Nouns substitute for nouns; verbs for verbs • Phonological Blends – Substitutions don’t result in – Gin and tonic Æ gin and topic ungrammatical sentences • Double Blends – Arrested and prosecuted Æ arrested and persecuted Word Stem & Affix Morphemes •A New Yorker Æ A New Yorkan (American) • Seem to occur prior to lexical insertion • Morphological rules of word formation engaged during speech production Stranding Errors • Nouns & Verbs exchange, but inflectional and derivational morphemes rarely do – Rather, they are stranded • I don’t know that I’d -

A Short and Easy

A SHORT A ND EASY MODERN GREEK GRAMMAR C a r l W ied l o t A SHORT AND EASY MODERN GREEK GRAMMAR. W ITH MMA TI A L D A T A EX E I GRA C A N CONVERS ION L RC SES, ID I MA TI PR VERBIAL PHRASES AND O C, O , B ULA Y F ULL VOCA R . FTER THE GERMAN OF CARL WIED MARY GARDNER WITH A PREFACE BY ERNEST GARD NER M A , . FELLOW O F G O VILLE A ND AIU O LLEGE AMBRI GE N C S C , C D , A ND R E BR F DI CTO R. O F THE ITISH SCHO O L O ARCHAEO LO GY A T ATHENS I onbon D A V ID NUTT 2 70 AND 2 7 1 STRAND 1 892 R I HAR LAY A ND O S IMITE C D C S N , L D , LO D B NDO N AN UNG AY . (Allrights reserved . ) ’ TRANSLATO R S PREFACE. MY very hearty t hanks are d ue to allwho have so kin dly helped V me m t t as F st m st t a Mr V ied an d t a e in y sligh k . ir I u h nk . , k the O pportunity t o ask his pardon for the amount of a lteration an d rearrangement of his text which I have found it impo ssib le t o a Mr L a h as a m an d t a s . e at e void . -

GF Modern Greek Resource Grammar

GF Modern Greek Resource Grammar Ioanna Papadopoulou University of Gothenburg [email protected] Abstract whilst each of the syntactic parts of the sentence (subject, object, predicate) is a carrier of a certain The paper describes the Modern Greek (MG) case, a fact that allows various word order Grammar, implemented in Grammatical structures. In addition, the language presents a Framework (GF) as part of the Grammatical dynamic syllable stress, whereas its position Framework Resource Grammar Library depends and alternates according to the (RGL). GF is a special-purpose language for morphological variations. Moreover, MG is one multilingual grammar applications. The RGL 1 is a reusable library for dealing with the of the two Indo-European languages that retain a morphology and syntax of a growing number productive synthetic passive formation. In order of natural languages. It is based on the use of to realize passivization, verbs use a second set of an abstract syntax, which is common for all morphological features for each tense. languages, and different concrete syntaxes implemented in GF. Both GF itself and the 2 Grammatical Framework RGL are open-source. RGL currently covers more than 30 languages. MG is the 35th GF (Ranta, 2011) is a special purpose language that is available in the RGL. For the programming language for developing purpose of the implementation, a morphology- multilingual applications. It can be used for driven approach was used, meaning a bottom- building translation systems, multilingual web up method, starting from the formation of gadgets, natural language interfaces, dialogue words before moving to larger units systems and natural language resources. -

The Process Model of Word Formation 65

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Repository of the Freie Universität Berlin Hans-Heinrich Lieb Towards a general theory of word formation: the Process Model Foreword The present essay—longer than a paper but shorter than a book—characterizes the Process Model of Word Formation that represents a new approach to word formation intermediate between constructionist and generative approaches; the model will be elaborated in detail in: Lieb, Hans-Heinrich (in prep.), The Process Model of Word Formation and Inflection . Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. The essay, which is independent of the book, re- places an earlier, unpublished manuscript (Lieb 2011/2012), of which it is a completely revised and enlarged version. The essay was completed in July 2013; it is an outcome of work undertaken by the author since roughly 2006 but originating from still earlier work (first presented at a Research Colloquium held at the Freie Universität Berlin in 2001, and subsequently by a lecture read at the Annual Meeting of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sprachwissenschaft in 2006: Lieb 2006). The present text is an Open Access publication by the Freie Universität Berlin; it is free for downloading, but all rights remain with the author (in particular, revamping of the text or its commercial use are prohibited; quotation only with indication of the source). The Freie Universität Berlin also houses a major effort at producing book-length Open Access publications in linguistics, organized into series: Language Science Press, langsci- press.org. The present essay does not fit this framework, both for lack of a suitable series and for being shorter than a book. -

153 Natasha Abner (University of Michigan)

Natasha Abner (University of Michigan) LSA40 Carlo Geraci (Ecole Normale Supérieure) Justine Mertz (University of Paris 7, Denis Diderot) Jessica Lettieri (Università degli studi di Torino) Shi Yu (Ecole Normale Supérieure) A handy approach to sign language relatedness We use coded phonetic features and quantitative methods to probe potential historical relationships among 24 sign languages. Lisa Abney (Northwestern State University of Louisiana) ANS16 Naming practices in alcohol and drug recovery centers, adult daycares, and nursing homes/retirement facilities: A continuation of research The construction of drug and alcohol treatment centers, adult daycare centers, and retirement facilities has increased dramatically in the United States in the last thirty years. In this research, eleven categories of names for drug/alcohol treatment facilities have been identified while eight categories have been identified for adult daycare centers. Ten categories have become apparent for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These naming choices function as euphemisms in many cases, and in others, names reference morphemes which are perceived to reference a higher social class than competitor names. Rafael Abramovitz (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) P8 Itai Bassi (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Relativized Anaphor Agreement Effect The Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE) is a generalization that anaphors do not trigger phi-agreement covarying with their binders (Rizzi 1990 et. seq.) Based on evidence from Koryak (Chukotko-Kamchan) anaphors, we argue that the AAE should be weakened and be stated as a generalization about person agreement only. We propose a theory of the weakened AAE, which combines a modification of Preminger (2019)'s AnaphP-encapsulation proposal as well as converging evidence from work on the internal syntax of pronouns (Harbour 2016, van Urk 2018). -

Lexicalization After Grammaticalization in the Development of Slovak Adjectives Ending In

Lexicalization after grammaticalization in the development of Slovak adjectives ending in -lý originating from l-participles Gabriela Múcsková, Comenius University and Slovak Academy of Sciences The paper deals with the development and current state of the Slovak participial forms, especially the participles with the formant -l- (the so-called l-participles) in the context of grammaticalization and lexicalization as complex and gradual changes. The analysis focuses on the group of “adjectives ending in -lý” as a result of “verb-to-adjective” lexicalization of former l-participles, which was conditioned by preceding grammaticalization of other members of the same participial paradigm. The group of lexemes identified in current Slovak descriptive grammatical and lexicographical works as “adjectives ending in -lý” is highly variable and includes a set of units of hybrid nature reflecting the overlapping of verbal and adjectival grammatical meanings and dynamic and static semantic components. Moreover, the group is rather limited, has irregular structural and derivational properties and is semantically rich, with extensive semantic derivation and polysemy. The characteristics of these units suggest a higher degree of their adjectivization, but the variability of the units reflects the different phases and degrees of this change, which was also influenced by language-planning factors in the Slovak historical context. Reconstruction of the phases of the adjectivization process, gradual decategorization and desemanticization, and reanalysis to a new structural and semantic class can serve as a contribution to more general questions about the nature of language change and its explanation. Keywords: participle, lexicalization, adjectivization, grammaticalization, lexicography 1. Introduction Linguistic descriptions of grammatical, word-formation and lexical structures are abstract reflexive constructs establishing boundaries between structural levels, parts of speech, categories and paradigms inside the language.