Yōsai and the Transformation of Buddhist Precepts in Pre‐Modern Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nihontō Compendium

Markus Sesko NIHONTŌ COMPENDIUM © 2015 Markus Sesko – 1 – Contents Characters used in sword signatures 3 The nengō Eras 39 The Chinese Sexagenary cycle and the corresponding years 45 The old Lunar Months 51 Other terms that can be found in datings 55 The Provinces along the Main Roads 57 Map of the old provinces of Japan 59 Sayagaki, hakogaki, and origami signatures 60 List of wazamono 70 List of honorary title bearing swordsmiths 75 – 2 – CHARACTERS USED IN SWORD SIGNATURES The following is a list of many characters you will find on a Japanese sword. The list does not contain every Japanese (on-yomi, 音読み) or Sino-Japanese (kun-yomi, 訓読み) reading of a character as its main focus is, as indicated, on sword context. Sorting takes place by the number of strokes and four different grades of cursive writing are presented. Voiced readings are pointed out in brackets. Uncommon readings that were chosen by a smith for a certain character are quoted in italics. 1 Stroke 一 一 一 一 Ichi, (voiced) Itt, Iss, Ipp, Kazu 乙 乙 乙 乙 Oto 2 Strokes 人 人 人 人 Hito 入 入 入 入 Iri, Nyū 卜 卜 卜 卜 Boku 力 力 力 力 Chika 十 十 十 十 Jū, Michi, Mitsu 刀 刀 刀 刀 Tō 又 又 又 又 Mata 八 八 八 八 Hachi – 3 – 3 Strokes 三 三 三 三 Mitsu, San 工 工 工 工 Kō 口 口 口 口 Aki 久 久 久 久 Hisa, Kyū, Ku 山 山 山 山 Yama, Taka 氏 氏 氏 氏 Uji 円 円 円 円 Maru, En, Kazu (unsimplified 圓 13 str.) 也 也 也 也 Nari 之 之 之 之 Yuki, Kore 大 大 大 大 Ō, Dai, Hiro 小 小 小 小 Ko 上 上 上 上 Kami, Taka, Jō 下 下 下 下 Shimo, Shita, Moto 丸 丸 丸 丸 Maru 女 女 女 女 Yoshi, Taka 及 及 及 及 Chika 子 子 子 子 Shi 千 千 千 千 Sen, Kazu, Chi 才 才 才 才 Toshi 与 与 与 与 Yo (unsimplified 與 13 -

The Old Tea Seller

For My Wife Yoshie Portrait of Baisaō. Ike Taiga. Inscription by Baisaō. Reproduced from Eastern Buddhist, No. XVII, 2. The man known as Baisaō, old tea seller, dwells by the side of the Narabigaoka Hills. He is over eighty years of age, with a white head of hair and a beard so long it seems to reach to his knees. He puts his brazier, his stove, and other tea implements in large bamboo wicker baskets and ports them around on a shoulder pole. He makes his way among the woods and hills, choosing spots rich in natural beauty. There, where the pebbled streams run pure and clear, he simmers his tea and offers it to the people who come to enjoy these scenic places. Social rank, whether high or low, means nothing to him. He doesn’t care if people pay for his tea or not. His name now is known throughout the land. No one has ever seen an expression of displeasure cross his face, for whatever reason. He is regarded by one and all as a truly great and wonderful man. —Fallen Chestnut Tales Contents PART 1: The Life of Baisaō, the Old Tea Seller PART 2: Translations Notes to Part 1 Selected Bibliography Glossary/Index Introductory Note THE BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH of Baisaō in the first section of this book has been pieced together from a wide variety of fragmented source material, some of it still unpublished. It should be the fullest account of his life and times yet to appear. As the book is intended mainly for the general reader, I have consigned a great deal of detailed factual information to the notes, which can be read with the text, afterwards, or disregarded entirely. -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Nengo Alpha.Xlsx

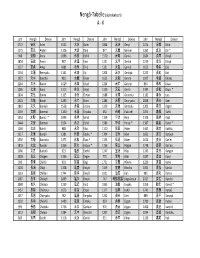

Nengô‐Tabelle (alphabetisch) A ‐ K Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise Jahr Nengō Devise 1772 安永 An'ei 1521 大永 Daiei 1864 元治 Genji 1074 承保 Jōhō 1175 安元 Angen 1126 大治 Daiji 877 元慶 Genkei 1362 貞治 Jōji * 968 安和 Anna 1096 永長 Eichō 1570 元亀 Genki 1684 貞享 Jōkyō 1854 安政 Ansei 987 永延 Eien 1321 元亨 Genkō 1219 承久 Jōkyū 1227 安貞 Antei 1081 永保 Eihō 1331 元弘 Genkō 1652 承応 Jōō 1234 文暦 Benryaku 1141 永治 Eiji 1204 元久 Genkyū 1222 貞応 Jōō 1372 文中 Bunchū 983 永観 Eikan 1615 元和 Genna 1097 承徳 Jōtoku 1264 文永 Bun'ei 1429 永享 Eikyō 1224 元仁 Gennin 834 承和 Jōwa 1185 文治 Bunji 1113 永久 Eikyū 1319 元応 Gen'ō 1345 貞和 Jōwa * 1804 文化 Bunka 1165 永万 Eiman 1688 元禄 Genroku 1182 寿永 Juei 1501 文亀 Bunki 1293 永仁 Einin 1184 元暦 Genryaku 1848 嘉永 Kaei 1861 文久 Bunkyū 1558 永禄 Eiroku 1329 元徳 Gentoku 1303 嘉元 Kagen 1469 文明 Bunmei 1160 永暦 Eiryaku 650 白雉 Hakuchi 1094 嘉保 Kahō 1352 文和 Bunna * 1046 永承 Eishō 1159 平治 Heiji 1106 嘉承 Kajō 1444 文安 Bunnan 1504 永正 Eishō 1989 平成 Heisei * 1387 嘉慶 Kakei * 1260 文応 Bun'ō 988 永祚 Eiso 1120 保安 Hōan 1441 嘉吉 Kakitsu 1317 文保 Bunpō 1381 永徳 Eitoku * 1704 宝永 Hōei 1661 寛文 Kanbun 1592 文禄 Bunroku 1375 永和 Eiwa * 1135 保延 Hōen 1624 寛永 Kan'ei 1818 文政 Bunsei 1356 延文 Enbun * 1156 保元 Hōgen 1748 寛延 Kan'en 1466 文正 Bunshō 923 延長 Enchō 1247 宝治 Hōji 1243 寛元 Kangen 1028 長元 Chōgen 1336 延元 Engen 770 宝亀 Hōki 1087 寛治 Kanji 999 長保 Chōhō 901 延喜 Engi 1751 宝暦 Hōreki 1229 寛喜 Kanki 1104 長治 Chōji 1308 延慶 Enkyō 1449 宝徳 Hōtoku 1004 寛弘 Kankō 1163 長寛 Chōkan 1744 延享 Enkyō 1021 治安 Jian 985 寛和 Kanna 1487 長享 Chōkyō 1069 延久 Enkyū 767 神護景雲 Jingo‐keiun 1017 寛仁 Kannin 1040 長久 Chōkyū 1239 延応 En'ō -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations A-8 Countries Eight countries that acceded to the CNDH Comisión Nacional de los Derechos European Union in 2004 on a transitional Humanos [[National Human Rights basis, the so-called 2-3-2 scheme (Czech Commission of Mexico] Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, CoC Certificate of (Good) Conduct Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia) CODENAF Cooperación al Desarrollo en el Norte de ACSUR- Asociación para la Cooperación con África [Development Cooperation in Las Segovias el Sur-Las Segovias [The Association for Northern Africa] Cooperation with the South] COMAR Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados ACVZ Adviescommissie voor Vreemdelingenzaken [Mexican Commission for Aid to Refugees] [Advisory Committee on Aliens' Affairs] COLEF El Colegio de la Frontera [del Norte/del AECID Agencia Española para la Cooperación Sur] [College of the Northern and Southern Internacional y el Desarrollo [Agency for Border, Mexico] International Development Cooperation] CPA Comprehensive Plan of Action for Indo- AIEC Australian International Education Chinese Refugees Conference CPSS Committee on Payment and Settlement AMC Asian Migration Centre Systems AMSED Association Marocaine de Solidarité et CQU Central Queensland University Développement [Moroccan Association for CRMGERG Chubu Region Multiculturalism and Gender Cooperation and Development] Equality Research Group ARENA Asian Research Exchange of New CRICOS Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Alternatives Courses for Overseas Students ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations CRLAF -

Chinese Religion and the Formation of Onmyōdō

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 40/1: 19–43 © 2013 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Masuo Shin’ichirō 増尾伸一郎 Chinese Religion and the Formation of Onmyōdō Onmyōdō is based on the ancient Chinese theories of yin and yang and the five phases. Practitioners of Onmyōdō utilizedYijing divination, magical puri- fications, and various kinds of rituals in order to deduce one’s fortune or to prevent unusual disasters. However, the term “Onmyōdō” cannot be found in China or Korea. Onmyōdō is a religion that came into existence only within Japan. As Onmyōdō was formed, it subsumed various elements of Chinese folk religion, Daoism, and Mikkyō, and its religious organization deepened. From the time of the establishment of the Onmyōdō as a government office under the ritsuryō codes through the eleventh century, magical rituals and purifications were performed extensively. This article takes this period as its focus, particularly emphasizing the connections between Onmyōdō and Chi- nese religion. keywords: Onmyōryō—ritsuryō system—Nihon shoki—astronomy—mikkyō— Onmyōdō rituals Masuo Shin’ichirō is a professor in the Faculty of Humanities at Tokyo Seitoku University. 19 he first reference to the Onmyōryō 陰陽寮 appears in the Nihon shoki 日本書紀. On the first day of the first month of 675 (Tenmu 4), various students of the Onmyōryō, the Daigakuryō 大学寮, and the Geyakuryō T外薬寮 (later renamed the Ten'yakuryō 典薬寮) are said to have paid tribute with medicine and rare treasures together with people from India, Bactria, Baekje, and Silla. On this day, the emperor took medicinal beverages such as toso 屠蘇 and byakusan 白散1 and prayed together with all his officials for longevity. -

Monumenta Nipponica Style Sheet

Monumenta Nipponica Style Sheet Completely revised edition SOPHIA UNIVERSITY, TOKYO Monumenta Nipponica Style Sheet Completely revised edition (May 2017) Sophia University 7–1 Kioi-chō, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 102-8554 Tel: 81-3-3238-3543; Fax: 81-3-3238-3835 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://dept.sophia.ac.jp/monumenta Copyright 2017 by Sophia University, all rights reserved. CONTENTS 1 GENERAL DIRECTIONS 1 1.1. Preparation of Manuscripts 1 1.2. Copyright 1 2 OVERVIEW OF STYLISTIC CONVENTIONS 2 2.1. Italics/Japanese Terms 2 2.2. Macrons and Plurals 2 2.3. Romanization 2 2.3.1. Word division 3 2.3.2. Use of hyphens 3 2.3.3. Romanization of Chinese and Korean names and terms 4 2.4. Names 4 2.5. Characters (Kanji/Kana) 4 2.6. Translation and Transcription of Japanese Terms and Phrases 4 2.7. Dates 5 2.8. Spelling, Punctuation, and Capitalization of Western Terms 5 2.9. Parts of a Book 6 2.10. Numbers 6 2.11. Transcription of Poetry 6 3 TREATMENT OF NAMES AND TERMS 7 3.1. Personal Names 7 3.1.1. Kami, Buddhist deities, etc. 7 3.1.2. “Go” emperors 7 3.1.3. Honorifics 7 3.2. Names of Companies, Publishers, Associations, Schools, Museums 7 3.3. Archives and Published Collections 8 3.4. Names of Prefectures, Provinces, Villages, Streets 8 3.5. Topographical Names 9 3.6. Religious Institutions and Palaces 9 3.7. Titles 10 3.7.1. Emperors, etc. 10 3.7.2. Retired emperors 10 3.7.3. -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

Download the Japan Style Sheet, 3Rd Edition

JAPAN STYLE SHEET JAPAN STYLE SHEET THIRD EDITION The SWET Guide for Writers, Editors, and Translators SOCIETY OF WRITERS, EDITORS, AND TRANSLATORS www.swet.jp Published by Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators 1-1-1-609 Iwado-kita, Komae-shi, Tokyo 201-0004 Japan For correspondence, updates, and further information about this publication, visit www.japanstylesheet.com Cover calligraphy by Linda Thurston, third edition design by Ikeda Satoe Originally published as Japan Style Sheet in Tokyo, Japan, 1983; revised edition published by Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, CA, 1998 © 1983, 1998, 2018 Society of Writers, Editors, and Translators All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher Printed in Japan Contents Preface to the Third Edition 9 Getting Oriented 11 Transliterating Japanese 15 Romanization Systems 16 Hepburn System 16 Kunrei System 16 Nippon System 16 Common Variants 17 Long Vowels 18 Macrons: Long Marks 18 Arguments in Favor of Macrons 19 Arguments against Macrons 20 Inputting Macrons in Manuscript Files 20 Other Long-Vowel Markers 22 The Circumflex 22 Doubled Letters 22 Oh, Oh 22 Macron Character Findability in Web Documents 23 N or M: Shinbun or Shimbun? 24 The N School 24 The M School 24 Exceptions 25 Place Names 25 Company Names 25 6 C ONTENTS Apostrophes 26 When to Use the Apostrophe 26 When Not to Use the Apostrophe 27 When There Are Two Adjacent Vowels 27 Hyphens 28 In Common Nouns and Compounds 28 In Personal Names 29 In Place Names 30 Vernacular Style -

NIHU Magazine Back Issues 3

https:/ /www.nihu.jp/en/publication/nihu_magazine Back Issues 3 : Vol.021 ~ Vol.030 Vol. 021 Rediscovering the Use and Value of Japan-Related Resources Recovered in the West Vol. 022 An interview with research fellows visiting NIHU – Dr. Andrew Houwen Vol. 023 An interview with research fellows visiting NIHU – Assistant Professor Helena Čapková Vol. 024 Interview Series “Yukinori Takubo, New Director-General, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL)” Vol. 025 An interview with research fellows visiting NIHU – Senior Lecturer Oleg Benesch Vol. 026 An interview with research fellows visiting NIHU – PhD student Lance Pursey Vol. 027 An interview with research fellows visiting NIHU – PhD candidate Jo McCallum Vol. 028 Five things you should know about Japanese era names before the end of Heisei Vol. 029 Arts and Humanities Research Council International Placement Scheme alumni gathered in Tokyo Vol. 030 Five things you should know about Expos, now that Osaka has won the bid to host the 2025 World Expo Vol. 021 Rediscovering the Use and Vlue of Japan-Related Resources Recovered in the West Many historical Japanese artifacts, such as the marvelous art and craft specimens collected by Philipp Franz von Siebold in Japan, which he then took back to Europe with him, are currently held in the collections of overseas research institutes. To promote the surveying and study of these Japan-related documents and artifacts, Japan’s National Institutes for the Humanities (NIHU) has undertaken a research program called “Japan-related Documents and Artifacts Held Overseas”. Under this research program, there are four research projects and a project that promotes the dissemination of research outcomes obtained by each of the four research projects. -

Representations of Travel in Medieval Japan by Kendra D. Strand A

Aesthetics of Space: Representations of Travel in Medieval Japan by Kendra D. Strand A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in The University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Emerita Professor Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen, Chair Associate Professor Kevin Gray Carr Professor Ken K. Ito, University of Hawai‘i Manoa Associate Professor Jonathan E. Zwicker © Kendra D. Strand 2015 Dedication To Gregory, whose adventurous spirit has made this work possible, and to Emma, whose good humor has made it a joy. ii Acknowledgements Kind regards are due to a great many people I have encountered throughout my graduate career, but to my advisors in particular. Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen has offered her wisdom and support unfalteringly over the years. Under her guidance, I have begun to learn the complexities in the spare words of medieval Japanese poetry, and more importantly to appreciate the rich silences in the spaces between those words. I only hope that I can some day attain the subtlety and dexterity with which she is able to do so. Ken Ito and Jonathan Zwicker have encouraged me to think about Japanese literature and to develop my voice in ways that would never have been possible otherwise, and Kevin Carr has always been incredibly generous with his time and knowledge in discussing visual cultural materials of medieval Japan. I am indebted to them for their patience, their attention, and for initiating me into their respective fields. I am grateful to all of the other professors and mentors with whom I have had the honor of working at the University of Michigan and elsewhere: Markus Nornes, Micah Auerback, Hitomi Tonomura, Leslie Pinkus, William Baxter, David Rolston, Miranda Brown, Laura Grande, Youngju Ryu, Christi Merrill, Celeste Brusati, Martin Powers, Mariko Okada, Keith Vincent, Catherine Ryu, Edith Sarra, Keller Kimbrough, Maggie Childs, and Dennis Washburn. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 11 Fall 2009 Special Issue Celebrating the Sixtieth Anniversary of the Institute of Buddhist Studies 1949–2009 Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Berkeley, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (15th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. Romanized Chinese follows Pinyin system (except in special cases); romanized Japanese, the modified Hepburn system. Japanese/Chinese names are given surname first, omit- ting honorifics. Ideographs preferably should be restricted to notes. Editorial Committee reserves the right to standardize use of or omit diacriticals.