Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Than One Way to Catch a Frog: a Study of Children's

More than one way to catch a frog: A study of children’s discourse in an Australian contact language Samantha Disbray Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne December, 2008 Declaration This is to certify that: a. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD b. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used c. the text is less than 100,000 words, exclusive of tables, figures, maps, examples, appendices and bibliography ____________________________ Samantha Disbray Abstract Children everywhere learn to tell stories. One important aspect of story telling is the way characters are introduced and then moved through the story. Telling a story to a naïve listener places varied demands on a speaker. As the story plot develops, the speaker must set and re-set these parameters for referring to characters, as well as the temporal and spatial parameters of the story. To these cognitive and linguistic tasks is the added social and pragmatic task of monitoring the knowledge and attention states of their listener. The speaker must ensure that the listener can identify the characters, and so must anticipate their listener’s knowledge and on-going mental image of the story. How speakers do this depends on cultural conventions and on the resources of the language(s) they speak. For the child speaker the development narrative competence involves an integration, on-line, of a number of skills, some of which are not fully established until the later childhood years. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Walakandha Wangga

Walakandha Wang ga Archival recordings by Marett et al. Notes by Marett, Barwick & Ford 1 THE INDIGENOUS MUSIC OF AUSTRALIA CD6 Ambrose Piarlum dancing wangga at a Wadeye circumcision ceremony, 1992. Photograph by Mark Crocombe, reproduced with the permission of Wadeye community. Walakandha Wangga THE INDIGENOUS MUSIC OF AUSTRALIA CD6 Archival recordings by Allan Marett, with supplementary recordings by Michael Enilane, Frances Kofod, William Hoddinott, Lesley Reilly and Mark Crocombe; curated and annotated by Allan Marett and Linda Barwick, with transcriptions and translations by Lysbeth Ford. Dedicated to the late Martin Warrigal Kungiung, Marett’s first wangga teacher Published by Sydney University Press © Recordings by Allan Marett, Michael Enilane, William Hoddinott, Frances Kofod, Lesley Reilly, & Mark Crocombe 2016 © Notes by Allan Marett, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Ford 2016 © Sydney University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this CD or accompanying booklet may be reproduced or utilised in any way or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher. Sydney University Press, Fisher Library F03, University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Web: sydney.edu.au/sup ISBN 9781743325292 Custodian statement This music CD and booklet contain traditional knowledge of the Marri Tjavin people from the Daly region of Australia’s Top End. They were created with the consent of the custodians. Dealing with any part of the music CD or the texts of the booklet for any purpose that has not been authorised by the custodians is a serious breach of the customary laws of the Marri Tjavin people, and may also breach the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth). -

Issues in Indigenous Digital Heritage Projects

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), Feature 3721–3738 1932–8036/2019FEA0002 Digitizing the Ancestors: Issues in Indigenous Digital Heritage Projects NICOLE STRATHMAN University of California, Riverside, USA Between 2002 and 2007, several university researchers (Christen, Ridington, and Hennessy; Shorter, Srinivasan, Verran, and Christie) collaborated with Indigenous communities to create digital heritage projects. Although the initial build and methodology surrounding the projects are well documented, the current status and end results are not. Now that a decade has passed since their production, this article examines the issues that have arisen with these Indigenous digital heritage projects. The primary emphasis is on sustainability, and the discussion concentrates on outdated software, funding problems, and maintenance issues that have afflicted these projects over the years. This study concludes that researchers need to take sustainability practices into consideration when creating specialized digital heritage projects. Keywords: digital heritage, virtual exhibition, content management system, sustainability, traditional knowledge, Indigenous, Native American, First Nations, Aboriginal Indigenous communities with access to information and communications technologies (ICTs) have used digital media to share their tangible and intangible culture and to store their vast bodies of knowledge.1 With a few clicks, the wisdom of their ancestors can be accessed by the world or by a select few members. Whether this knowledge takes the form of the visual arts, traditional storytelling and songs, repatriated objects, or digital documents, the issues remain the same: What material is being displayed? Who has access? How is the site maintained? University researchers have worked with Indigenous communities in creating digital heritage projects to help address these questions (Christen, 2008; Ridington & Hennessy, 2008; Shorter, 2006; Srinivasan, 2007; Verran & Christie, 2007). -

14 Annu a L Repo

20 t R l Repo A 14 Annu The Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language is an ARC funded centre of excellence (CE140100041). College of Asia and the Pacifc The Australian National Unviersity H.C. Coombs Building Fellows Road, Acton ACT 2601 Email: [email protected] Phone: (02) 6125 9376 www.dynamicsofanguage.edu.au www.facebook.com/CoEDL © ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language 2014 Design: Sculpt Communications ARC Centre of excellence for the Dynamics of language Annual Report 2014 table of contents Section 1: The Centre 7 Section 2: People 25 Section 3: Research 49 Section 4: Education, Training and Mentoring 75 Section 5: Outreach and Engagement 81 Section 6: Outputs 90 Section 7: Financials 103 Section 8: Performance indicators 105 7 one on I t C e S 01tHe CentRe HEADING HEADING Introducing the ARC Centre of excellence for the Dynamics of language 8 Using language is as natural as breathing, and almost as important, for using language transforms every aspect of human experience. But it has been extraordinarily diffcult to understand its evolution, diversifcation, and use: a vast array of incredibly different language systems are found across the planet, all representing different solutions to the problem of evolving a fexible, all-purpose communication system, and all in constant fux. The ARC Centre of Excellence for the To achieve this transformation of the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) will shift language sciences and the fow-on the focus of the language sciences from the translational outcomes for the public and long-held dominant view that language is a end-users, we have assembled a team which static and genetically constrained system — makes surprising and bold connections to a dynamic model where diversity, variation, between areas of research that until now plasticity and evolution, along with complex have not been connected: linguistics, interactions between language-learning and speech pathology, psychology, anthropology, perceptual and cognitive processes, lie at the philosophy, bioinformatics and robotics. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

Noun Phrase Constituency in Australian Languages: a Typological Study

Linguistic Typology 2016; 20(1): 25–80 Dana Louagie and Jean-Christophe Verstraete Noun phrase constituency in Australian languages: A typological study DOI 10.1515/lingty-2016-0002 Received July 14, 2015; revised December 17, 2015 Abstract: This article examines whether Australian languages generally lack clear noun phrase structures, as has sometimes been argued in the literature. We break up the notion of NP constituency into a set of concrete typological parameters, and analyse these across a sample of 100 languages, representing a significant portion of diversity on the Australian continent. We show that there is little evidence to support general ideas about the absence of NP structures, and we argue that it makes more sense to typologize languages on the basis of where and how they allow “classic” NP construal, and how this fits into the broader range of construals in the nominal domain. Keywords: Australian languages, constituency, discontinuous constituents, non- configurationality, noun phrase, phrase-marking, phrasehood, syntax, word- marking, word order 1 Introduction It has often been argued that Australian languages show unusual syntactic flexibility in the nominal domain, and may even lack clear noun phrase struc- tures altogether – e. g., in Blake (1983), Heath (1986), Harvey (2001: 112), Evans (2003a: 227–233), Campbell (2006: 57); see also McGregor (1997: 84), Cutfield (2011: 46–50), Nordlinger (2014: 237–241) for overviews and more general dis- cussion of claims to this effect. This idea is based mainly on features -

Commonwealth of Australia

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of The Charles Darwin University with permission from the author(s). Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander THESAURUS First edition by Heather Moorcroft and Alana Garwood 1996 Acknowledgements ATSILIRN conference delegates for the 1st and 2nd conferences. Alex Byrne, Melissa Jackson, Helen Flanders, Ronald Briggs, Julie Day, Angela Sloan, Cathy Frankland, Andrew Wilson, Loris Williams, Alan Barnes, Jeremy Hodes, Nancy Sailor, Sandra Henderson, Lenore Kennedy, Vera Dunn, Julia Trainor, Rob Curry, Martin Flynn, Dave Thomas, Geraldine Triffitt, Bill Perrett, Michael Christie, Robyn Williams, Sue Stanton, Terry Kessaris, Fay Corbett, Felicity Williams, Michael Cooke, Ely White, Ken Stagg, Pat Torres, Gloria Munkford, Marcia Langton, Joanna Sassoon, Michael Loos, Meryl Cracknell, Maggie Travers, Jacklyn Miller, Andrea McKey, Lynn Shirley, Xalid Abd-ul-Wahid, Pat Brady, Sau Foster, Barbara Lewancamp, Geoff Shepardson, Colleen Pyne, Giles Martin, Herbert Compton Preface Over the past months I have received many queries like "When will the thesaurus be available", or "When can I use it". Well here it is. At last the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Thesaurus, is ready. However, although this edition is ready, I foresee that there will be a need for another and another, because language is fluid and will change over time. As one of the compilers of the thesaurus I am glad it is finally completed and available for use. -

How Warumungu People Express New Concepts Jane Simpson Tennant

How Warumungu people express new concepts Jane Simpson Tennant Creek 16/10/85 [This paper appeared in a lamentedly defunct journal: Simpson, Jane. 1985. How Warumungu people express new concepts. Language in Central Australia 4:12-25.] I. Introduction Warumungu is a language spoken around Tennant Creek (1). It is spoken at Rockhampton Downs and Alroy Downs in the east, as far north as Elliott, and as far south as Ali Curung. Neighbouring languages include Alyawarra, Kaytej, Jingili, Mudbura, Wakaya, Wampaya, Warlmanpa and Warlpiri. In the past, many of these groups met together for ceremonies and trade. There were also marriages between people of different language groups. People were promised to 'close family' from close countries. Many children would grow up with parents who could speak different languages. This still happens, and therefore many people are multi-lingual - they speak several languages. This often results in multi-lingual conversation. Sometimes one person will carry on their side of the conversation in Warumungu, while the other person talks only in Warlmanpa. Other times a person will use English, Warumungu, Alyawarra, Warlmanpa, and Warlpiri in a conversation, especially if different people take part in it. The close contact between speakers of different languages shows in shared words. For example, many words for family-terms are shared by different languages. As Valda Napururla Shannon points out, Eastern Warlpiri ("wakirti" Warlpiri (1)) shares words with its neighbours, Warumungu and Warlmanpa, while Western Warlpiri shares words with its neighbours. Pintupi, Gurindji, Anmatyerre etc. In Eastern Warlpiri, Warlmanpa and Warumungu the word "kangkuya" is used for 'father's father' (or 'father's father's brother' or 'father's father's sister'). -

A PDF Combined with Pdfmergex

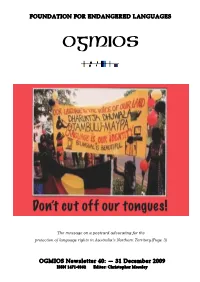

!"#$%&'("$)!"*)+$%&$,+*+%)-&$,#&,+.) ) OGMIOS The message on a postcard advocating for the protection of language rights in Australia’s Northern Territory (Page 3) ",/(".)$012304405)678)9):;)%0<0=>05)?77@) (..$);6A;B7:C?))))))+DE4F58)GH5E24FIH05)/F2030J) 2 DEBFD<'C4G"64$$4+'HI,'J'KL'=4/4M14+'NIIO' F<<C'LHPLQIKRN''''''()#$*+,'07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;' !""#"$%&$'()#$*+,'!)+#%&*'-+."/*$$' 0*&$+#1.$#&2'()#$*+",'3*24+'564&/78'9*"4:7'56;$748'<4+4&%'=>!2*"$#&*8'07+#"$*:74+'?%)@#46)8'A+%&/#"'B'?.6$8'' C#/7*6%"'D"$64+8'!&)+4%'3#$$4+' ' !"#$%&$'$()'*+,$"-'%$.' /012,3()+'14.' ' 07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;8' A*.&)%$#*&'@*+'(&)%&24+4)'X%&2.%24"8' O'S4"$)4&4'0+4"/4&$8' LPN'5%#61+**Y'X%&48'' 0%T4+"7%M'?4#27$"8' 5%$7'5!L'P!!8'(&26%&)' 34%)#&2'3EH'P?=8'(&26%&)' &*"$64+V/7#1/7%W)4M*&W/*W.Y'' /7+#"M*"464;UIV;%7**W/*M'' 'GGGW*2M#*"W*+2' The Austronesian Languages......................................... 19! LW'()#$*+#%6 3! Immersion – a film on endangered languages ............... 19! Cover Story: Northern Territory’s small languages sidelined from schools ...................................................... 3! RW'\6%/4"'$*'2*'*&'$74'S41 20! NW! =4T46*:M4&$'*@'$74'A*.&)%$#*& 4! Irish upside down............................................................ 20! Resolution of the FEL XIII Conference, Khorog, Tajikistan, OW'A*+$7/*M#&2'4T4&$" 21! 26, September, 2009 ........................................................ 4! HRELP Workshop: Endangered Languages, endangered FEL and UNESCO Atlas partnership................................ 4! knowledge & sustainability............................................. -

Following the Nyinkka: Relations of Respect and Obligations to Act in the Collaborative Work of Aboriginal Cultural Centers

MUA3002_02.qxd 8/16/07 4:43 PM Page 101 101 Following the Nyinkka: Relations of Respect and Obligations to Act in the Collaborative Work of Aboriginal Cultural Centers Kimberly Christen hile John McDouall Stuart and his Australia. Every hundred kilometers or so a sign expedition party attempted to “open” the reminds weary travelers that this seemingly empty Winterior of Australia to white settlers land is indeed “settled.” A final pyramid-shaped between 1858 and 1862, he charted the seemingly brick memorial sits on the western side of the high- monotonous terrain in his journal:“this plain has the way as one enters the small town of Tennant Creek same appearance now as when I first started– from the south.1 spinifex and gum-trees, with a little scrub occasion- Down the road from Stuart’s memorial, on the ally” (Hardman 1865:164–174).The terrain was also same side of the highway, a set of buildings and unforgiving to those unfamiliar with its intricacies. another series of plaques marks the landscape. Over several excursions, Stuart and his entourage Dwarfing Stuart’s memorial, the Nyinkka Nyunyu were thwarted by harsh climates, an unpredictable Art and Culture Centre sits just off the main road landscape, and ill health. On December 20, 1861, (figure 1). Entering through the main gates, follow- with failing health and a stubborn will to reach the ing the winding path past the visitor center and café, north of the continent, Stuart embarked on what one comes upon a pile of large black rocks behind a would be a successful journey. -

Four Circles, the Law Man and the Stars

Justice and equity in Bill Harney’s Imulun Wardaman Aboriginal spiritual law Four Circles, the Law Man and the Stars by Hugh Cairns and Bill Idumduma Harney A Northern Australian People with their intellectual legal world of the Four Circles tradition Dedication As I switched on my television in Sydney this week, there was Bill Harney! Dapper, well turned out, his bush hat slanted in his usual way, he was seated in the third row of the Federal Court sitting in Mataranka, Northern Territory. Calm and secure in aspect, he was listening to the Judge as the Court formally acknowledged the Native Title of the Aboriginal town, only the third town in Australia to receive this. The Elsie cattle station and its black families had been made famous by the pioneer Gunns of ‘We of the Never Never’: now, members of Communities and Land Councils from all over the continent were applauding the High Court’s original Native Title Decision of 1992-3, the hard work of individuals like Bill Harney who since those days had persevered in the Tribunals and hundreds of other meetings and field surveys on behalf of the Originals of the claimed lands, and the lawyers and judges who had – bravely with intellectual integrity – found decisively for this Law of the Land. This is an active man, caring and courageous and hard-working, in his eighty-second year. Last month he was in Alice Springs with Men Elders and Women Elders, pleading for the Government to stop the 2007 Intervention, and its Income Management policies and practices, from being extended for another ten years: its devastations, in many Communities he knows well, should not be allowed to continue.