Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and Legal Problems of First Sixty Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

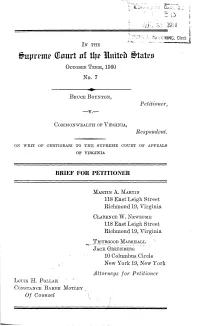

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT AND FREEDOM RIDES 1961 By: Angelica Narvaez Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott vCharles Hamilton Houston, an African-American lawyer, challenged lynching, segregated public schools, and segregated transportation vIn 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses, but gained it little attention vIn 1953, a bus boycott in Baton Rouge partially integrated city buses vWomen’s Political Council (WPC) v An organization comprised of African-American women led by Jo Ann Robinson v Failed to change bus companies' segregation policies when meeting with city officials Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) vVirginia's law allowed bus companies to establish segregated seating in their buses vDuring 1944, Irene Morgan was ordered to sit at the back of a Greyhound Bus v Refused and was arrested v Refused to pay the fine vNAACP lawyers William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall contested the constitutionality of segregated transportation v Claimed that Commerce Clause of Article 1 made it illegal v Relatively new tactic to argue segregation with the commerce clause instead of the 14th Amendment v Did not claim the usual “states rights” argument Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) v Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law v Deemed segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional v “Found that Virginia's law clearly interfered with interstate commerce by making it necessary for carriers to establish different rules depending on which state line their vehicles crossed” v Made little -

The Freedom Rides of 1961

The Freedom Rides of 1961 “If history were a neighborhood, slavery would be around the corner and the Freedom Rides would be on your doorstep.” ~ Mike Wiley, writer & director of “The Parchman Hour” Overview Throughout 1961, more than 400 engaged Americans rode south together on the “Freedom Rides.” Young and old, male and female, interracial, and from all over the nation, these peaceful activists risked their lives to challenge segregation laws that were being illegally enforced in public transportation throughout the South. In this lesson, students will learn about this critical period of history, studying the 1961 events within the context of the entire Civil Rights Movement. Through a PowerPoint presentation, deep discussion, examination of primary sources, and watching PBS’s documentary, “The Freedom Riders,” students will gain an understanding of the role of citizens in shaping our nation’s democracy. In culmination, students will work on teams to design a Youth Summit that teaches people their age about the Freedom Rides, as well as inspires them to be active, engaged community members today. Grade High School Essential Questions • Who were the key players in the Freedom Rides and how would you describe their actions? • Why do you think the Freedom Rides attracted so many young college students to participate? • What were volunteers risking by participating in the Freedom Rides? • Why did the Freedom Rides employ nonviolent direct action? • What role did the media play in the Freedom Rides? How does media shape our understanding -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Amelia Boynton Robinson

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Amelia Boynton Robinson Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Robinson, Amelia Boynton, 1911- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Amelia Boynton Robinson, Dates: September 4, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 7 Betacame SP videocasettes (3:24:55). Description: Abstract: Civil rights leader Amelia Boynton Robinson (1911 - 2015 ) was one of the civil rights leaders that led the famous first march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which became known as Bloody Sunday. She was also the first African American woman ever to seek a seat in Congress from Alabama. Robinson was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 4, 2007, in Tuskegee, Alabama. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_244 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Civil rights pioneer Amelia Boynton Robinson was born on August 18, 1911, in Savannah, Georgia. As a young lady, Robinson became very active in women’s suffrage. In 1934, at the age of twenty-three, Robinson became one of the few registered African American voters. In an era where literacy tests were used to discriminate against African Americans seeking to vote, Robinson used her status as a registered voter to assist other African American applicants to become registered voters. In 1930, while working as a home economics teacher in the rural south, Robinson became re-acquainted with Sam William Boynton, an extension agent for the county whom she had met while studying at Tuskegee Institute. -

Vision Winter 2008

FOR UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO ALUMNI AND FRIENDS NorthernNorthernVISION WINTER 2008 UNC’S JAZZ PROGRAM CONTInuES JJaaA TRADITIOzzN OF EzzXCELLEnceeE dd SPECIAL SECTION REPORT ON GIVING CANCER REHABILITATION INSTITUTE >> HONORS AND SCHOLARS Call 970.351.4TIX (4849) or visit www.uncbears.com www.uncbears.com WINTER 2008 DEPARTMENTS contentsFEATURES 3 10 A Smooth Melody The UNC Jazz Studies Program continues to build a reputation as one of the country’s best 14 8 2 Letters 18 3 Northern News 8 Bears Sports 22 Giving Back 14 A Higher Learning The Center for Honors, Scholars and 23 Alumni News Leadership challenges students to go 24 Alumni Profile beyond education to think for themselves 25 Class Notes 18 Transforming Lives 32 Calendar of Events UNC’s Rocky Mountain Cancer Rehabilitation Institute changes the way patients, students and professionals think about cancer recovery ON THE COVER SPECIAL SECTION FOR UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO The University of Northern ALUMNI AND FRIENDS Colorado Big Band ensemble, 25 WINTER 2008 NorthernVISION photographed after a perfor- Report 23 mance at the University Center, was named Best College Big on Giving Band by Down Beat magazine. This was the seventh award in Transforming UNC’S JAZZ PROGRAM CONTINUES NorthernVISION A TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE the past five years for the Jazz Lives Through Jazzed Studies Program. Education SPECIAL SECTION REPORT ON GIVING Vol. 5 No. 2 CANCER REHABILITATION INSTITUTE >> HONORS AND SCHOLARS PHOTOGRAPH BY ERIK STENBAKKEN 33 NORTHERN VISION < UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO > 1 lettersREADER This is an egregious error. I realize China 101 Editor that no one pays admission to see these Danyel Barnard THE SIDEBAR on the article “China 101” students run, but a cross country meet Alumni/Class Notes Editor in the fall 2007 issue said that the China is a true spectator sport where fans can Margie Meyer trip was the first three-week faculty- get close to the runners, cheer them on Contributing Writers taught study abroad course. -

The Civil Rights Movement

Star Lecture with Professor Lou Kushnick GLOSSARY The glossary is divided into the following categories: Laws and Acts, Events and Locations, Terminology and Events and Locations. LAWS ANDS ACTS 13TH AMENDMENT Adopted in 1864. Abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in all States. Adopted in 1868. Allows Blacks to be determined to be United States Citizens. Overturned previous ruling in Dred 14TH AMENDMENT Scott v. Sandford of 1857. Adopted in 1970. Bans all levels of government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based 15TH AMENDMENT on that citizen's "race, colour, or previous condition of servitude" BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION A landmark Supreme Court decision in 1954 that declared segregated education as unconstitutional. This victory was a launchpad for other challenges to de jure segregation in other field of public life – including transportation. Like many challenges to segregation, Brown was a case presented by a collection of individuals in a class action lawsuit – one of whom was Oliver Brown, who was unhappy that his child had travel a number of block to attend a Black school when a White school was much nearer. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court it actually encompassed a number of cases brought by parents against School Boards. The funds for the legal challenges were provided by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This wide-reaching Act prohibited racial and gender discrimination in public services and areas. It was originally created by President Kennedy, but was signed into existence after his assassination by President Johnson. -

The Road to Civil Rights Table of Contents

The Road to Civil Rights Table of Contents Introduction Dred Scott vs. Sandford Underground Railroad Introducing Jim Crow The League of American Wheelmen Marshall “Major” Taylor Plessy v. Ferguson William A. Grant Woodrow Wilson The Black Migration Pullman Porters The International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters The Davis-Bacon Act Adapting Transportation to Jim Crow The 1941 March on Washington World War II – The Alaska Highway World War II – The Red Ball Express The Family Vacation Journey of Reconciliation President Harry S. Truman and Civil Rights South of Freedom Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Too Tired to Move When Rulings Don’t Count Boynton v. Virginia (1960) Freedom Riders Completing the Freedom Ride A Night of Fear Justice in Jackson Waiting for the ICC The ICC Ruling End of a Transition Year Getting to the March on Washington The Civil Rights Act of 1964 The Voting Rights March The Pettus Bridge Across the Bridge The Voting Rights Act of 1965 March Against Fear The Poor People’s Campaign Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Completing the Poor People’s Campaign Bureau of Public Roads – Transition Disadvantaged Business Enterprises Rodney E. Slater – Beyond the Dreams References 1 The Road to Civil Rights By Richard F. Weingroff Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, "Wait." But when . you take a cross country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you . then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. -

Stepping Into Selma: Voting Rights History and Legacy Today

Stepping Into Selma: Voting Rights History and Legacy Today Background In this 50th anniversary year of the Selma-to-Montgomery March and the Voting Rights Act it helped inspire, national media will predictably focus on the iconic images of “Bloody Sunday,” the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the interracial marchers, and President Lyndon Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act. This version of history, emphasizing a top-down narrative and isolated events, reinforces the master narrative that civil rights activists describe as “Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and the white folks came south to save the day.” But there is a “people’s history” of Selma that we all can learn from—one that is needed, especially now. The exclusion of Blacks and other people of color from voting is still a live issue. Sheriff’s deputies may no longer be beating people to keep them from registering to vote, but institutionalized racism continues. For example, in 2013 the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby v. Holder that the Justice Department may no longer evaluate laws passed in the former Confederacy for racial bias. And as a new movement emerges, insisting that “Black Lives Matter,” young people can draw inspiration and wisdom from the courage, imagination, and accomplishments of activists who went before. [From article by Emilye Crosby.] This lesson on the people in Selma’s voting rights movement is based on an effective format that has been used with students and teachers to introduce a variety of themes including the history and literature of Central America, the U.S. -

![Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [Audiotapes]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6000/guide-to-the-moses-moon-collection-audiotapes-3916000.webp)

Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [Audiotapes]

Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [audiotapes] NMAH.AC.0556 Wendy Shay Partial funding for preservation and duplication of the original audio tapes provided by a National Museum of American History Collections Committee Jackson Fund Preservation Grant. Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Original Tapes.......................................................................................... 6 Series 2: Preservation Masters............................................................................. -

The Alabama Lawyer in the January and March Issues of the Alabamalawyer, We Asked for Your Opinion of the Lawyer

Theawyer Alabama MAY1993 t t ver the years commercial malpractice insurers have come and gone from the Alabama marketplace. End the worry about prior acts coverage . Insure with AIM. We're here when you need us: Continuously! AIM: For the Difference (We're here to stay!) "A Mutual Insurance Company Organized by and for Alabama Attorneys" Attorneys Insurance Mutual of Alabama , Inc.• 22 Inverness Center' Pa,kway Te lephone (205) 980-0009 Sui te 340 To ll Free (800) 526 - 1246 Birmingham. A labama 35242 -4820 FAX(205)980 - 9009 •CHARTER MEMBER : NATIONAL ASSOCIA T ION O F BAR-RELATED INSURANCE COMPANIES InAlabama family law, one referencesource contains everything a practicingattorney needs. his one-volume source offers family law prac1i1ioncrs all the tools for guiding clients 1hrough~ 1e gauruleLof family dispu1es: s1a1u1es,c,1se law. fonns. and prnc1ical advice on every aspect of handling the c-ase. ©Wriucn by 1wo of Alabama's 1op family law expem, Rick Fernambucq and Judge Gary Pale, i1 provides quick access 10 s1a1:eand federal l.1wsaffect ing the case: prac1ical rccon1n1endations Cordea ling with trau1natizedc lients: aJ,d proven fonns, pleadings. and motions used 1hroughou1 1he Alabama domes1ic cour1s. such as: • Cliem lnfonna1ion Fom1 • Motion to Intervene • Motion for Ex Pal'le Temporary Res1n1ining Order • Complain! for Modilication {UCCJA and PKPA) • Request for Productions • lntenogatories (Divorce and Post-Divorce Ac1ion) • Qualilied Domes1ic Relations Order (pursuan1 10 Equi1y Retiremen1 Act of 1984 ) FAMILY LAW IN ALABAMA ,----- IBE------ ------ by Fernambucq and Pate Up-to-date coverage, i11c/11di11g fo rms, MICHJE~ tifr keeps your case 011tra ck. -

Amelia Robinson Launches Libel Suit Vs. ABC, Disney TV

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 8, Number 4, Winter 1999 Amelia Robinson Launches Libel Suit vs. ABC, ivil Rights leader Amelia Boynton CRobinson, who is vice chairman of the Schiller Institute, filed a libel suit in August against the American Broad- casting Corporation, Walt Disney Tele- vision, and other parties involved in the production of the Disney television movie “Selma, Lord, Selma,” which aired nationwide Jan. 17, 1999 on the “Wonderful World of Disney” pro- gram. The subject of the movie is the 1965 Civil Rights struggle in Selma, Alabama, in which Mrs. Robinson was a leading figure. It was she who invited Dr. Martin Luther King to come to Selma to help her and her husband, EIRNS/Stuart Lewis S.W. Boynton, lead the struggle for vot- Schiller Institute vice chairman Amelia Boynton Robinson (right) shares podium honors ing rights there. with Institute founder Helga Zepp LaRouche, September 1999. ‘This Is Not Me’ The body of the suit recounts Mrs. ments, and particularly her leading role Mrs. Robinson told Fidelio that she had Robinson’s numerous accomplishments in the Selma battle (recounted in her declined to participate in filming the and awards in her 88 years of life, most autobiography Bridge Across Jordan, movie because, after discussing the plans of them spent in service of the Civil published by the Schiller Institute), to with the actress assigned to play her Rights movement. Just with respect to the “Black mammy” stereotype with part, the daughter of Civil Rights leader voters’ rights, Mrs. Robinson has been which she is portrayed in the movie—a Hosea Williams, Mrs. -

The Selma Voting Rights Struggle: 15 Key Points from Bottom-Up History and Why It Matters Today

The Selma Voting Rights Struggle: 15 Key Points from Bottom-Up History and Why It Matters Today A shorter version of this article, "Ten Things You Should Know About Selma Before You See the Film," is available on Common Dreams at http://bit.ly/10thingsselma. Free downloadable lessons and resources to bring this bottom-up history to the classroom are available at http://bit.ly/teachselma. For an online version of this article with related resources, visit http://bit.ly/selma15. By Emilye Crosby On this 50th anniversary year of the Selma-to-Montgomery March and the Voting Rights Act it helped inspire, national attention is centered on the iconic images of "Bloody Sunday," the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the interracial marchers, and President Lyndon Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act. This version of history, emphasizing a top-down narrative and isolated events, reinforces the master narrative that civil rights activists describe as "Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and the white folks came south to save the day." Today, issues of racial equity and voting rights are front and center in the lives of young people. There is much they can learn from an accurate telling of the Selma (Dallas County) voting rights campaign and the larger Civil Rights Movement. We owe it to students on this anniversary to share the history that can help equip them to carry on the struggle today. A march of 15,000 in Harlem in solidarity with the Selma voting rights struggle. World Telegram & Sun photo by Stanley Wolfson. Library of Congress © Teaching for Change | teachingforchange.org 1 1.