Social Activism Through Shareholder Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

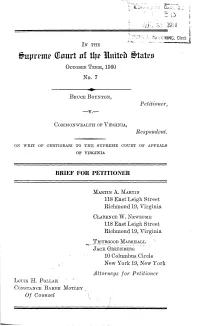

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation

09-Mollin 12/2/03 3:26 PM Page 113 The Limits of Egalitarianism: Radical Pacifism, Civil Rights, and the Journey of Reconciliation Marian Mollin In April 1947, a group of young men posed for a photograph outside of civil rights attorney Spottswood Robinson’s office in Richmond, Virginia. Dressed in suits and ties, their arms held overcoats and overnight bags while their faces carried an air of eager anticipation. They seemed, from the camera’s perspective, ready to embark on an exciting adventure. Certainly, in a nation still divided by race, this visibly interracial group of black and white men would have caused people to stop and take notice. But it was the less visible motivations behind this trip that most notably set these men apart. All of the group’s key organizers and most of its members came from the emerging radical pacifist movement. Opposed to violence in all forms, many had spent much of World War II behind prison walls as conscientious objectors and resisters to war. Committed to social justice, they saw the struggle for peace and the fight for racial equality as inextricably linked. Ardent egalitarians, they tried to live according to what they called the brotherhood principle of equality and mutual respect. As pacifists and as militant activists, they believed that nonviolent action offered the best hope for achieving fundamental social change. Now, in the wake of the Second World War, these men were prepared to embark on a new political jour- ney and to become, as they inscribed in the scrapbook that chronicled their traveling adventures, “courageous” makers of history.1 Radical History Review Issue 88 (winter 2004): 113–38 Copyright 2004 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT AND FREEDOM RIDES 1961 By: Angelica Narvaez Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott vCharles Hamilton Houston, an African-American lawyer, challenged lynching, segregated public schools, and segregated transportation vIn 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses, but gained it little attention vIn 1953, a bus boycott in Baton Rouge partially integrated city buses vWomen’s Political Council (WPC) v An organization comprised of African-American women led by Jo Ann Robinson v Failed to change bus companies' segregation policies when meeting with city officials Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) vVirginia's law allowed bus companies to establish segregated seating in their buses vDuring 1944, Irene Morgan was ordered to sit at the back of a Greyhound Bus v Refused and was arrested v Refused to pay the fine vNAACP lawyers William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall contested the constitutionality of segregated transportation v Claimed that Commerce Clause of Article 1 made it illegal v Relatively new tactic to argue segregation with the commerce clause instead of the 14th Amendment v Did not claim the usual “states rights” argument Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) v Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law v Deemed segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional v “Found that Virginia's law clearly interfered with interstate commerce by making it necessary for carriers to establish different rules depending on which state line their vehicles crossed” v Made little -

The Freedom Rides of 1961

The Freedom Rides of 1961 “If history were a neighborhood, slavery would be around the corner and the Freedom Rides would be on your doorstep.” ~ Mike Wiley, writer & director of “The Parchman Hour” Overview Throughout 1961, more than 400 engaged Americans rode south together on the “Freedom Rides.” Young and old, male and female, interracial, and from all over the nation, these peaceful activists risked their lives to challenge segregation laws that were being illegally enforced in public transportation throughout the South. In this lesson, students will learn about this critical period of history, studying the 1961 events within the context of the entire Civil Rights Movement. Through a PowerPoint presentation, deep discussion, examination of primary sources, and watching PBS’s documentary, “The Freedom Riders,” students will gain an understanding of the role of citizens in shaping our nation’s democracy. In culmination, students will work on teams to design a Youth Summit that teaches people their age about the Freedom Rides, as well as inspires them to be active, engaged community members today. Grade High School Essential Questions • Who were the key players in the Freedom Rides and how would you describe their actions? • Why do you think the Freedom Rides attracted so many young college students to participate? • What were volunteers risking by participating in the Freedom Rides? • Why did the Freedom Rides employ nonviolent direct action? • What role did the media play in the Freedom Rides? How does media shape our understanding -

Community Foundation of Jackson Hole Annual

COMMUNITY FOUNDATION OF JACKSON HOLE ANNUAL REPORT / 2018 TA B L E Welcome Letter 3 OF CONTENTS About Us 4 Donor Story 6 Professional Development & Resources 8 Competitive Grants 10 Youth Philanthropy 12 Micro Grants 16 Opportunities Fund 18 Collective Impact 20 Legacy Society 24 1 Fund Highlights 24-25 Key Financial Indicators 26 Donor Story 28 The Foundation Circle 30 Community Foundation Funds 34 Old Bill’s Fun Run 36 Co-Challengers 38 Friends of the Match 42 Gifts to Funds 44 Community Foundation of Teton Valley 46 Behind the Scenes 48 In Memoriam 50 Community Foundation of Jackson Hole / Annual Report 2018 2 Fund & Program Highlight HELLO, Mr. and Mrs. Old Bill say it best. They have always led with the question, “How can we help?” Their initial vision was to inspire “we” to become “all of us.” And it has. In 2018, you raised an astonishing amount, bringing Old Bill’s Fun Run’s 22-year total to more than $159 million for local nonprofits. Inside these pages, you will see the impact of our remarkable community’s generosity. In fact, one out of every three families in Teton County takes part in Old Bill’s—an event that has become a national model for collaborative fundraising. Old Bill’s lasts only a morning, but because of your support, we are touching lives and working for the community 3 every day. Nonprofits rely on us for professional workshops and resources and receive critical funding through our Competitive and Capacity Building grant opportunities. We convene Community Conversations to find collaborative solutions to local problems. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Amelia Boynton Robinson

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Amelia Boynton Robinson Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Robinson, Amelia Boynton, 1911- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Amelia Boynton Robinson, Dates: September 4, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 7 Betacame SP videocasettes (3:24:55). Description: Abstract: Civil rights leader Amelia Boynton Robinson (1911 - 2015 ) was one of the civil rights leaders that led the famous first march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which became known as Bloody Sunday. She was also the first African American woman ever to seek a seat in Congress from Alabama. Robinson was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 4, 2007, in Tuskegee, Alabama. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_244 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Civil rights pioneer Amelia Boynton Robinson was born on August 18, 1911, in Savannah, Georgia. As a young lady, Robinson became very active in women’s suffrage. In 1934, at the age of twenty-three, Robinson became one of the few registered African American voters. In an era where literacy tests were used to discriminate against African Americans seeking to vote, Robinson used her status as a registered voter to assist other African American applicants to become registered voters. In 1930, while working as a home economics teacher in the rural south, Robinson became re-acquainted with Sam William Boynton, an extension agent for the county whom she had met while studying at Tuskegee Institute. -

June/July 2010 Education Coordinator by Rosalie Nagler I N T H I S I S S U E As We Move Into Summer in East Tennessee, We Look Forward to New Beginnings

Heska Amuna Welcomes New Rabbi, Volume 2 ♦ Issue 6 ♦ June/July 2010 Education Coordinator By Rosalie Nagler I N T H I S I S S U E As we move into summer in East Tennessee, we look forward to new beginnings. We welcome a new rabbi who Heska Amuna HaShofar starts in August with the the arrival of Rabbi Alon Ferency From the Rabbi’s Desk……………...1 and his wife, Karen. They come to us from Los Angeles, where Rabbi Ferency graduated in May from the Ziegler From the Chair...………………..….1 School of Rabbinic Studies. By birth, Rabbi Ferency is from Kitchen & Kiddush News………......3 the northeast, having grown up in Massachusetts. He HARS News………………..…..….….4 attended Harvard and has traveled extensively. We anticipate welcoming him to ―Volunteer Country‖ with typical southern hospitality. Among Our Members…………...….6 Anna Iroff will be our religious school coordinator. Anna comes to us as one of our Contributions……………………......6 ―kids‖ who grew up at Heska Amuna and went on to study at the Albert A. List College of Jewish Studies, an undergraduate program of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. While studying there, Anna also worked as a religious school teacher and is very Temple Beth El Times excited to guide our religious school. She has taught the Confirmation class the past two years and and adult education classes. We look forward to her collaborating with Rabbi From the Rabbi’s Study….………..11 Ferency to create a bright future for the next generation of Heska Amuna ―kids!‖ President’s Message…………..…...12 As you can see, Heska Amuna Synagogue has many opportunities open to us for a renewal in our congregation. -

Papers of the Naacp

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr., Sharon Harley, and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part Selected Branch Files, 27 1956-1965 Series B: The Northeast UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr., Sharon Harley, and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 27: Selected Branch Files, 1956-1965 Series B: The Northeast Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr., Sharon Harley, and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 --[etc.]--pt. 27. Selected Branch Files, 1956-1965. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People--Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century--Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations--Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923-. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Title. E185.61 [Microfilm] 973'.0496073 86-892185 ISBN 1-55655-760-4 (microfilm: pt. 27, series B) Copyright © 2001 by University Publications of America. -

Freedom Riders Democracy in Action a Study Guide to Accompany the Film Freedom Riders Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation

DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS DEMOCRACY IN ACTION A STUDY GUIDE TO ACCOMPANY THE FILM FREEDOM RIDERS Copyright © 2011 by WGBH Educational Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover art credits: Courtesy of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Back cover art credits: Bettmann/CORBIS. To download a PDF of this guide free of charge, please visit www.facinghistory.org/freedomriders or www.pbs.org/freedomriders. ISBN-13: 978-0-9819543-9-4 ISBN-10: 0-9819543-9-1 Facing History and Ourselves Headquarters 16 Hurd Road Brookline, MA 02445-6919 ABOUT FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES Facing History and Ourselves is a nonprofit and the steps leading to the Holocaust—the educational organization whose mission is to most documented case of twentieth-century engage students of diverse backgrounds in an indifference, de-humanization, hatred, racism, examination of racism, prejudice, and antisemitism antisemitism, and mass murder. It goes on to in order to promote a more humane and explore difficult questions of judgment, memory, informed citizenry. As the name Facing History and legacy, and the necessity for responsible and Ourselves implies, the organization helps participation to prevent injustice. Facing History teachers and their students make the essential and Ourselves then returns to the theme of civic connections between history and the moral participation to examine stories of individuals, choices they confront in their own lives, and offers groups, and nations who have worked to build a framework and a vocabulary for analyzing the just and inclusive communities and whose stories meaning and responsibility of citizenship and the illuminate the courage, compassion, and political tools to recognize bigotry and indifference in their will that are needed to protect democracy today own worlds. -

Charles A. Person Was Born September 27, 1942 and Educated in Atlanta

Charles A. Person was born September 27, 1942 and educated in Atlanta. He graduated in 1960 from David T. Howard High School as Class Salutatorian. Mr. Person is a veteran of the Vietnam War and also of the Civil Rights Movement. He saw action in Da Nang; Chu Lai, Okinawa; Washington DC; Charlotte North Carolina; New Orleans, Louisiana and Atlanta, Georgia. During his days in the Civil Rights Movement, the Klu Klux Klan savagely beat him in Anniston, Alabama and, again, in Birmingham, Alabama. Numerous medals and ribbons have been awarded to Mr. Person for his hard work and dedication. He retired from the United States Marine Corps in 1981 on the island of Cuba. He remained at Guantanamo Bay Navy Base where he managed an electronic maintenance company for three years. After his retirement from the Marine Corps, Mr. Person continued his career with the Atlanta Public School System as an Electronic Technician. Today, Mr. Person and his wife reside in his hometown Atlanta and are the parents of five children. He is an activist within the community and the NAACP. “LOOK AROUND... WHAT CHANGE NEEDS TO HAPPEN? GET ON THE BUS. MAKE IT HAPPEN.” – CHARLES PERSON A firsthand exploration of the cost of boarding the bus of change to move America forward – written by one of the Civil Rights Movement’s pioneers. At 18, Charles Person was the youngest of the original Freedom Riders. This mix of activists – including future Congressman John Lewis, Congress of Racial Equality Director James Farmer, Reverend Benjamin Elton Cox, journalist and pacifist James Peck, and CORE field secretary Genevieve Hughes – set out by bus in 1961 to discover whether America would abide by a Supreme Court decision that ruled segregation unconstitutional in bus depots, waiting areas, restaurants and restrooms nationwide. -

Introduction

Introduction And those people who are working to bring into being the dream of democracy are not the agitators. They are not the dangerous people in America. They are not the un-American people. They are people who are doing more for America than anybody that we can point to. And I submit to you that it may well be that the Negro is God’s instrument to save the soul of America. Martin Luther King, Jr. 2 January 1961 When forty-three-year-old John F. Kennedy took office on 20 January 1961 as the youngest elected American president, Martin Luther King Jr. had just turned thirty- two but had already risen to national prominence as a result of his leadership role in the Montgomery bus boycott that ended four years earlier. Early in 1957 he had become founding president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and subsequently was in great demand as a speaker throughout the nation. His understanding of Gandhian principles had deepened as a result of his 1959 trip to India, but, during the following year, college student sit-in protesters, rather than King, became the vanguard of a sustained civil disobedience campaign. Having already weathered a near-fatal stabbing and six arrests, King was uncertain about how best to support the new militancy. Moving to Atlanta to be near SCLC head- quarters and to serve as co-pastor with his father at Ebenezer Baptist Church, he had assumed a wide range of responsibilities. He relied on his wife, Coretta Scott, to take the lead role of raising their two small children with a third due any day.