The Road to Civil Rights Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

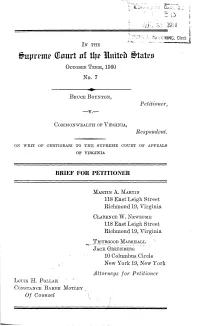

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 16-111 In the Supreme Court of the United States MASTERPIECE CAKESHOP, LTD., et al., Petitioners, v. COLORADO CIVIL RIGHTS COMMISSION, et al., Respondents. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE COURT OF APPEALS OF COLORADO BRIEF FOR LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS, COLOR OF CHANGE, THE LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE OF CIVIL AND HUMAN RIGHTS, NATIONAL ACTION NETWORK, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE AND SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS KRISTEN CLARKE ILANA H. EISENSTEIN JON GREENBAUM Counsel of Record DARIELY RODRIGUEZ COURTNEY GILLIGAN SALESKI DORIAN SPENCE ETHAN H. TOWNSEND LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE PAUL SCHMITT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW ADAM STEENE 1401 New York Avenue JEFFREY DEGROOT Washington, D.C. 20008 DLA PIPER LLP (US) (202) 662-8600 One Liberty Place 1650 Market Street, Suite 4900 Philadelphia, PA 19109 (215) 656-3300 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae 276433 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS..........................i TABLE OF APPENDICES ......................iii TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES ..............iv INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ..................1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .....................2 ARGUMENT....................................4 I. Civil Rights Laws Have Played an Integral Role in Rooting Out Discrimination in Public Accommodations .....................4 II. This Court Has Emphatically Upheld State and Federal Public Accommodation Laws Against Free Speech Challenges and Colorado’s Law Should Be No Different .......8 A. Masterpiece’s attempt, supported by the federal government, to create a new exception to public accommodation laws fails .............................12 B. The federal government’s attempt to distinguish this case based on sexual orientation also fails ...................18 ii Table of Contents Page III. -

Black History Month Friday Morning Meeting 2018

Black History Month Friday Morning Meeting 2018 Quiz Questions and Answers 1) Do you know when the idea of Black History Month was established? Answer: Black History month has been nationally recognized since 1976, although Dr. Carter G. Woodson created it in 1926. Growing out of “Negro History Week”, which was celebrated between Abraham Lincoln’s birthday (February 12) and Frederick Douglass’ birthday (February 20), it is a designated time in which the achievements of Black people are recognized. 2) Do you know how long the Pan-African flag has existed? Answer: The Pan-African flag was created in 1920 to represent the pride of African- American people. The red band is for the “blood that unifies African descendants”, the black is to affirm the existence of Black people and green reminds people about the “vegetation of the motherland”. 3) Do you know how many museums in the United States are dedicated to African- American culture or history? Answer: There are over 150 museums dedicated to African-American culture and history in the country. The first was established in 1868 at the historically Black college, Hampton University in Hampton, VA. The largest museum was the Charles H. Wright museum of Detroit, Michigan, which was founded in 1965. However, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture completed in 2016 has exceeded it in size. 4) Do you know how many visits to the National Museum of African American History and Culture have been recorded since its opening? Answer: The Smithsonian Institution has a museum dedicated to African-American culture and history? Located in the heart of Washington, D.C., it has over 36,000 artifacts highlighting subjects like community, the arts, civil rights, and slavery. -

Civil Rights Done Right – Browder V. Gayle

Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Browder v. Gayle sample TEACHING TOLERANCE Table of Contents Introduction 2 STEP ONE Self Assessment 3 Lesson Inventory 4 Pre-Teaching Reflection 5 STEP TWO The "What" of Teaching the Movement 6 Essential Content Areas 7 Essential Content Coverage Sample 8 Essential Content Checklist 9 STEP THREE The "How" of Teaching the Movement 11 Implementing the Five Essential Practices Sample 12 Essential Practices Checklist 13 STEP FOUR Planning for Teaching the Movement 14 Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Sample 15 STEP FIVE Teaching the Movement 19 Post-Teaching Reflection 20 © 2016 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT: BROWDER V. GAYLE SAMPLE // 1 TEACHING TOLERANCE Civil Rights Done Right A Tool for Teaching the Movement Not long ago, Teaching Tolerance issued Teaching the Movement, a report evaluating how well social studies standards in all 50 states support teaching about the modern civil rights movement. Our report showed that few states emphasize the movement or provide classroom support for teaching this history effectively. We followed up these findings by releasingThe March Continues: Five Essential Practices for Teaching the Civil Rights Movement, a set of guiding principles for educators who want to improve upon the simplified King-and-Parks-centered narrative many state standards offer. Those essential practices are: 1. Educate for empowerment. 2. Know how to talk about race. 3. Capture the unseen. 4. Resist telling a simple story. 5. Connect to the present. Civil Rights Done Right offers a detailed set of curriculum improvement strategies for classroom instructors who want to apply these practices. -

Conrad Lynn to Speak at New York Forum

gtiiinimmiimiHi JOHNSON MOVES TO EXPLOIT HEALTH ISSUE THE Medicare As a Vote-Catching Gimmick By M arvel Scholl paign promises” file and dressed kept, so he can toss them around 1964 is a presidential election up in new language. as liberally as necessary, be in year so it is not surprising that Johnson and his Administration dignant, give facts and figures, President Johnson’s message to know exactly how little chance deplore and propose. MILITANT Congress on health and medical there is that any of the legislation He states that our medical sci Published in the Interests of the Working People care should sound like the he proposes has of getting through ence and all its related disciplines thoughtful considerations of a man the legislative maze of “checks are “unexcelled” but — each year Vol. 28 - No. 8 Monday, February 24, 1964 Price 10c and a party deeply concerned over and balances” (committees to thousands of infants die needless the general state of health of the committees, amendments, change, ly; half of the young men un entire nation. It is nothing of the debate and filibuster ad infini qualified for military services are kind. It is a deliberate campaign tum). Words are cheap, campaign rejected for medical reasons; one hoax, dragged out of an old “cam- promises are never meant to be third of all old age public as sistance is spent for medical care; Framed-Up 'Kidnap' Trial most contagious diseases have been conquered yet every year thousands suffer and die from ill nesses fo r w hich there are know n Opens in Monroe, N. -

Original Freedom Riders to Be Honored with Theatrical Performance/Award

Contacts: Contact: Jackie Madden, (469) 853-5582, [email protected] For Immediate Release Jan. 17, 2018 ORIGINAL FREEDOM RIDERS TO BE HONORED WITH THEATRICAL PERFORMANCE/AWARD (IRVING) — Free Theatrical Presentation—As part of Irving’s Martin Luther King Jr celebration, Irving Parks and Recreation and Irving Arts Center will present Freedom Riders, a new play with original songs and music produced by Mad River Theater Works. Two performances will be offered on January 21, at 2:30 p.m. and 6:30 p.m. Jan. 21, in Carpenter Hall at the Irving Arts Museum, 3333 N. MacArthur Blvd., Irving. The performances are FREE but are first come, first served with tickets being made available one hour before show time, day of show. No advance tickets will be offered. Special Presentation to Honor Original Freedom Riders, William Harbour and Charles Person Following each performance, Irving Community Television Network Producer Cathy Whiteman will moderate a post-show question and answer segment, featuring two of the 13 original Freedom Riders William E. Harbour and Charles Person. They will be presented 2018 Civil Rights Legacy Awards. About Freedom Riders Mad River Theater Works’ Freedom Riders demonstrates the importance of working together to affect change and specifically how non-violent protest was used to combat the cruelties of segregation. Freedom riders, both black and white, mostly young, Americans, decided to travel together on buses that crossed state lines purposefully disregarding the hateful segregation practices that were still commonplace in so many parts of the United States. The play, recommended for ages 9 and up, explores the valiant and courageous personalities behind one of the most critical chapters in the history of the Civil Rights movement. -

Memory of the Civil Rights Movement in Textbooks, Juvenile Biography, and Museums

ABSTRACT JOHNSON, CHRISTINE RENEE GOULD. Celebrating a National Myth: Memory of The Civil Rights Movement in Textbooks, Juvenile Biography, and Museums. (Under the direction of Dr. Katherine Mellen Charron). The Civil Rights Movement (CRM) is commemorated at movement anniversaries, during Black History Month, and every Martin Luther King Jr. Day. However, some historians argue these public versions do not tell a full story of the CRM, over-simplifying it and portraying it as a story of inevitable progress. Relying on a “mythic” version of this critical event in the nation’s history, the mainstream narrative has little explanatory power. This makes it easier for some to dismiss ongoing struggles for racial equality and more difficult for future generations to learn from movement’s successes and failures. This thesis examines other kinds of CRM history that inform the public. Many learn about the movement as youth through educational mediums like high school textbooks and children’s literature, and people of all ages encounter it in museums. I ask what version of CRM history each of these present, inquiring how interpretations have evolved over time and the degree to which they reflect changes in scholarship. Spanning a total of fifty-four years, this study finds surprisingly little change in textbook narratives beyond token additions that nod to some advancements in the historiography. Juvenile biographies of CRM luminaries published in recent decades present a deeper history, often with a longer chronology, but relay an overly optimistic outlook about what the movement accomplished. Civil rights museums in the South vary in their depictions, with the strongest interpretations appearing in the most recently opened or renovated. -

African Americans in the Military

African Americans in the Military While the fight for African American civil rights has been traditionally linked to the 1960s, the discriminatory experiences faced by black soldiers during World War II are often viewed by historians as the civil rights precursor to the 1960s movement. During the war America’s dedication to its democratic ideals was tested, specifically in its treatment of its black soldiers. The hypocrisy of waging a war on fascism abroad, yet failing to provide equal rights back home was not lost. The onset of the war brought into sharp contrast the rights of white and black American citizens. Although free, African Americans had yet to achieve full equality. The discriminatory practices in the military regarding black involvement made this distinction abundantly clear. There were only four U.S. Army units under which African Americans could serve. Prior to 1940, thirty thousand blacks had tried to enlist in the Army, but were turned away. In the U.S. Navy, blacks were restricted to roles as messmen. They were excluded entirely from the Air Corps and the Marines. This level of inequality gave rise to black organizations and leaders who challenged the status quo, demanding greater involvement in the U.S. military and an end to the military’s segregated racial practices. Soldiers Training, ca. 1942, William H. Johnson, oil on plywood, Smithsonian American Art Museum Onset of War The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 irrevocably altered the landscape of World War II for blacks and effectively marked the entry of American involvement in the conflict. -

Fair Housing Act)

Civil Rights Movement Rowland Scherman for USIA, Photographer. Courtesy of U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Sections 1 About the Movement 5 Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Fair Housing Act) 2 Brown v. Board of Education 6 Teacher Lesson Plans and Resources 3 Civil Rights Act of 1964 4 Voting Rights Act (VRA) ABOUT THE MOVEMENT The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s came about out of the need and desire for equality and freedom for African Americans and other people of color. Nearly one hundred years after slavery was abolished, there was widespread 1 / 22 segregation, discrimination, disenfranchisement and racially motivated violence that permeated all personal and structural aspects of life for black people. “Jim Crow” laws at the local and state levels barred African Americans from classrooms and bathrooms, from theaters and train cars, from juries and legislatures. During this period of time, there was a huge surge of activism taking place to reverse this discrimination and injustice. Activists worked together and used non- violent protest and specific acts of targeted civil disobedience, such as the MontgomMontgomMontgomMontgomererereryyyy Bus BusBusBus Bo BoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott and the Greensboro Woolworth Sit-Ins, in order to bring about change. Much of this organizing and activism took place in the Southern part of the United States; however, people from all over the country—of all races and religions—joined activists to proclaim their support and commitment to freedom and equality. For example, on August 28, 1963, 250,000 Americans came to Washington, D.C. for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT AND FREEDOM RIDES 1961 By: Angelica Narvaez Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott vCharles Hamilton Houston, an African-American lawyer, challenged lynching, segregated public schools, and segregated transportation vIn 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses, but gained it little attention vIn 1953, a bus boycott in Baton Rouge partially integrated city buses vWomen’s Political Council (WPC) v An organization comprised of African-American women led by Jo Ann Robinson v Failed to change bus companies' segregation policies when meeting with city officials Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) vVirginia's law allowed bus companies to establish segregated seating in their buses vDuring 1944, Irene Morgan was ordered to sit at the back of a Greyhound Bus v Refused and was arrested v Refused to pay the fine vNAACP lawyers William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall contested the constitutionality of segregated transportation v Claimed that Commerce Clause of Article 1 made it illegal v Relatively new tactic to argue segregation with the commerce clause instead of the 14th Amendment v Did not claim the usual “states rights” argument Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) v Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law v Deemed segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional v “Found that Virginia's law clearly interfered with interstate commerce by making it necessary for carriers to establish different rules depending on which state line their vehicles crossed” v Made little -

Diagnosis Nabj: a Preliminary Study of a Post-Civil Rights Organization

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository DIAGNOSIS NABJ: A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF A POST-CIVIL RIGHTS ORGANIZATION BY LETRELL DESHAN CRITTENDEN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor John Nerone, Chair Associate Professor Christopher Benson Associate Professor William Berry Associate Professor Clarence Lang, University of Kansas ABSTRACT This critical study interrogates the history of the National Association of Black Journalists, the nation’s oldest and largest advocacy organization for reporters of color. Founded in 1975, NABJ represents the quintessential post-Civil Rights organization, in that it was established following the end of the struggle for freedom rights. This piece argues that NABJ, like many other advocacy organizations, has succumbed to incorporation. Once a fierce critic of institutional racism inside and outside the newsroom, NABJ has slowly narrowed its advocacy focus to the issue of newsroom diversity. In doing so, NABJ, this piece argues, has rendered itself useless to the larger black public sphere, serving only the needs of middle-class African Americans seeking jobs within the mainstream press. Moreover, as the organization has aged, NABJ has taken an increasing amount of money from the very news organizations it seeks to critique. Additionally, this study introduces a specific method of inquiry known as diagnostic journalism. Inspired in part by the television show, House MD, diagnostic journalism emphasizes historiography, participant observation and autoethnography in lieu of interviewing. -

Building Racial Bridges: Why We Can't Wait by Martin Luther King, Jr

Building Racial Bridges: Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King, Jr. February 2, 2016 Discussion led by Collin College Professor Michael Phillips Background information: “Jim Crow” was a character in the minstrel shows where white entertainers would blacken their faces and perform satirical reviews of current events as if they were African Americans. The Jim Crow Laws came to set the boundaries of segregation. Racial separation rose after slavery and became legal in the 1880’s. At that time poor whites had the distinction of never being someone’s property, bought or sold, or families separated. With the 13th (abolishing slavery), 14th (giving blacks citizenship), and 15th (giving blacks voting rights) amendments being passed, poor whites became discontent. They had no distinctive rights over the Negro. Populism, a radical movement working for justice and equal rights for all, rose in the 1880’s and ‘90’s. It involved the support of both black and white farmers working together toward economic justice and represented a threat to the Southern economic power structure. Two types of segregation: De jure – by law, evident in the South (separate schools, doors for public places, separate Bibles for swearing in, even the emergency blood supply, black women not allowed to try on or even touch clothes before purchase) De facto – practiced in the North (understood parameters, cultural, redlining in which banks and realtors would keep people of color out of certain neighborhoods) Populist Movement collapsed in 1896 with the re-establishing of segregation laws. 1919 Red Summer – labeled for the volume of blood shed, whites attacking blacks.