Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

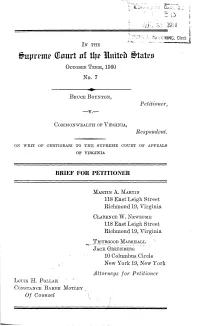

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

REFLECTION REFLECTION the Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights Movement

REFLECTION REFLECTION The Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights Movement “I’m taking a trip on the Greyhound bus line, I’m riding the front seat to New Orleans this time. Hallelujah I’m a travelin’, hallelujah ain’t it fine, Hallelujah I’m a travelin’ down freedom’s main line.” This reflection is based on the PBS documentary, “Freedom Riders,” which is a production of The American Experience. To watch the film, go to: http://to.pbs.org/1VbeNVm. SUMMARY OF THE FILM From May to November 1961, over 400 Americans, both black and white, witnessed the power of nonviolent activism for civil rights. The Freedom Riders were opposing the racist Jim Crow laws of the South by riding bus lines from Washington, D.C., down through the Deep South. These Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Despite the violence, threats, and extraor- dinary racism they faced, people of conscience, both black and white, Northern and Southern, rich and poor, old and young, carried out the Freedom Rides as a testimony to the basic truth all Americans hold: that the government must protect the constitutional rights of its people. Finally, on September 22, 1961, segregation on the bus lines ended. This was arguably the movement that changed the force and effectiveness of the Civil Rights Movement as a whole and set the stage for other organized movements like the Selma to Montgomery March and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This documentary is based on the book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Equality by Raymond Arsenault (http://bit.ly/1Vbn4sy). -

Movement 1954-1968

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 1954-1968 Tuesday, November 27, 12 NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AFFAIRS Curated by Ben Hazard Tuesday, November 27, 12 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, The initial phase of the black protest activity in the post-Brown period began on December 1, 1955. Rosa Parks of Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat to a white bus rider, thereby defying a southern custom that required blacks to give seats toward the front of buses to whites. When she was jailed, a black community boycott of the city's buses began. The boycott lasted more than a year, demonstrating the unity and determination of black residents and inspiring blacks elsewhere. Martin Luther King, Jr., who emerged as the boycott movement's most effective leader, possessed unique conciliatory and oratorical skills. He understood the larger significance of the boycott and quickly realized that the nonviolent tactics used by the Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi could be used by southern blacks. "I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom," he explained. Although Parks and King were members of the NAACP, the Montgomery movement led to the creation in 1957 of a new regional organization, the clergy-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) with King as its president. King remained the major spokesperson for black aspirations, but, as in Montgomery, little-known individuals initiated most subsequent black movements. On February 1, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College began a wave of student sit-ins designed to end segregation at southern lunch counters. -

How Did the Civil Rights Movement Impact the Lives of African Americans?

Grade 4: Unit 6 How did the Civil Rights Movement impact the lives of African Americans? This instructional task engages students in content related to the following grade-level expectations: • 4.1.41 Produce clear and coherent writing to: o compare and contrast past and present viewpoints on a given historical topic o conduct simple research summarize actions/events and explain significance Content o o differentiate between the 5 regions of the United States • 4.1.7 Summarize primary resources and explain their historical importance • 4.7.1 Identify and summarize significant changes that have been made to the United States Constitution through the amendment process • 4.8.4 Explain how good citizenship can solve a current issue This instructional task asks students to explain the impact of the Civil Rights Movement on African Claims Americans. This instructional task helps students explore and develop claims around the content from unit 6: Unit Connection • How can good citizenship solve a current issue? (4.8.4) Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task 1 Performance Task 2 Performance Task 3 Performance Task 4 How did the 14th What role did Plessy v. What impacts did civic How did Civil Rights Amendment guarantee Ferguson and Brown v. leaders and citizens have legislation affect the Supporting Questions equal rights to U.S. Board of Education on desegregation? lives of African citizens? impact segregation Americans? practices? Students will analyze Students will compare Students will explore how Students will the 14th Amendment to and contrast the citizens’ and civic leaders’ determine the impact determine how the impacts that Plessy v. -

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and The

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968 Black Belt Press The ONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT M and the WOMEN WHO STARTED IT __________________________ The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson __________________________ Mrs. Jo Ann Gibson Robinson Black women in Montgomery, Alabama, unlocked a remarkable spirit in their city in late 1955. Sick of segregated public transportation, these women decided to wield their financial power against the city bus system and, led by Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (1912-1992), convinced Montgomery's African Americans to stop using public transportation. Robinson was born in Georgia and attended the segregated schools of Macon. After graduating from Fort Valley State College, she taught school in Macon and eventually went on to earn an M.A. in English at Atlanta University. In 1949 she took a faculty position at Alabama State College in Mont- gomery. There she joined the Women's Political Council. When a Montgomery bus driver insulted her, she vowed to end racial seating on the city's buses. Using her position as president of the Council, she mounted a boycott. She remained active in the civil rights movement in Montgomery until she left that city in 1960. Her story illustrates how the desire on the part of individuals to resist oppression — once *it is organized, led, and aimed at a specific goal — can be transformed into a mass movement. Mrs. T. M. Glass Ch. 2: The Boycott Begins n Friday morning, December 2, 1955, a goodly number of Mont- gomery’s black clergymen happened to be meeting at the Hilliard O Chapel A. -

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

Nominees and Bios

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Pre‐Emancipation Period 1. Emanuel Driggus, fl. 1645–1685 Northampton Co. Enslaved man who secured his freedom and that of his family members Derived from DVB entry: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Driggus_Emanuel Emanuel Driggus (fl. 1645–1685), an enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and several members of his family exemplified the possibilities and the limitations that free blacks encountered in seventeenth‐century Virginia. His name appears in the records of Northampton County between 1645 and 1685. He might have been the Emanuel mentioned in 1640 as a runaway. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor are the date and circumstances of his arrival in Virginia. His name, possibly a corruption of a Portuguese surname occasionally spelled Rodriggus or Roddriggues, suggests that he was either from Africa (perhaps Angola) or from one of the Caribbean islands served by Portuguese slave traders. His first name was also sometimes spelled Manuell. Driggus's Iberian name and the aptitude that he displayed maneuvering within the Virginia legal system suggest that he grew up in the ebb and flow of people, goods, and cultures around the Atlantic littoral and that he learned to navigate to his own advantage. 2. James Lafayette, ca. 1748–1830 New Kent County Revolutionary War spy emancipated by the House of Delegates Derived from DVB/ EV entry: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lafayette_James_ca_1748‐1830 James Lafayette was a spy during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Born a slave about 1748, he was a body servant for his owner, William Armistead, of New Kent County, in the spring of 1781. -

Biography Bottle Project Due Date: February 3, 2015 Students Will

Biography Bottle Project Due Date: February 3, 2015 Students will learn as they celebrate Black History Month in February, by (1) researching facts {biographies/auto‐biographies/non‐fiction text} to write a 3 paragraph essay, in school, and (2) creating a Biography Bottles Statue/Image, at home, that will be displayed in our school library, during the month of February. It is important that all the deadlines listed below are met so that students do not fall behind and miss the due dates. The subject for the bio‐bottle project will be a famous African American that is selected, from a given list, by students and approved by the teacher on January 15th. The reading/research for this project will be done at home and at school. The reading/research should be completed by Wednesday, January 21st. Please have parents sign and return the slips listed below to teachers by Wednesday, January 21st. The completed Biography Bottle Statue/Image is due on Tuesday, February 3rd . Attached to this document is the grading rubric that I will use to for the bio bottle project. Materials needed for the bottle: 1 plastic bottle . For example: Small water or soda bottle 2 liter soda bottle Ketchup bottle Dish soap bottle o Please note the a minimum size should be at least 16 ounces, and the maximum size should be a 2 liter bottle Sand, dirt, or gravel to put in the bottom of your bottle to anchor it Things to decorate your bottle to look like the person you have researched . For example: Paint, yarn, glue, sequins, felt, beads, feathers, colored paper, pipe cleaners, Styrofoam balls, fabric, buttons, clay, googly eyes, etc. -

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

100 Facts About Rosa Parks on Her 100Th Birthday

100 Facts About Rosa Parks On Her 100th Birthday By Frank Hagler SHARE Feb. 4, 2013 On February 4 we will celebrate the centennial birthday of Rosa Parks. In honor of her birthday here is a list of 100 facts about her life. 1. Rosa Parks was born on Feb 4, 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. ADVERTISEMENT Do This To Fix Car Scratches This car gadget magically removes scratches and scuffs from your car quickly and easily. trynanosparkle.com 2. She was of African, Cherokee-Creek, and Scots-Irish ancestry. FEATURED VIDEOS Powered by Sen Gillibrand reveals why she's so tough on Al Franken | Mic 2020 NOW PLAYING 10 Sec 3. Her mother, Leona, was a teacher. 4. Her father, James McCauley, was a carpenter. 5. She was a member of the African Methodist Episcopal church. 6. She attended the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery. 7. She attended the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes for secondary education. 8. She completed high school in 1933 at the age of 20. 9. She married Raymond Parker, a barber in 1932. 10. Her husband Raymond joined the NAACP in 1932 and helped to raise funds for the Scottsboro boys. 11. She had no children. 12. She had one brother, Sylvester. 13. It took her three tries to register to vote in Jim Crow Alabama. 14. She began work as a secretary in the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943. 15. In 1944 she briefly worked at Maxwell Air Force Base, her first experience with integrated services. 16. One of her jobs within the NAACP was as an investigator and activist against sexual assaults on black women. -

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

CASE STUDY The Montgomery Bus Boycott What objectives, targets, strategies, demands, and rhetoric should a nascent social movement choose as it confronts an entrenched system of white supremacy? How should it make decisions? Peter Levine December 2020 SNF Agora Case Studies The SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University offers a series of case studies that show how civic and political actors navigated real-life challenges related to democracy. Practitioners, teachers, organizational leaders, and trainers working with civic and political leaders, students, and trainees can use our case studies to deepen their skills, to develop insights about how to approach strategic choices and dilemmas, and to get to know each other better and work more effectively. How to Use the Case Unlike many case studies, ours do not focus on individual leaders or other decision-makers. Instead, the SNF Agora Case Studies are about choices that groups make collectively. Therefore, these cases work well as prompts for group discussions. The basic question in each case is: “What would we do?” After reading a case, some groups role-play the people who were actually involved in the situation, treating the discussion as a simulation. In other groups, the participants speak as themselves, dis- cussing the strategies that they would advocate for the group described in the case. The person who assigns or organizes your discussion may want you to use the case in one of those ways. When studying and discussing the choices made by real-life activists (often under intense pres- sure), it is appropriate to exhibit some humility. You do not know as much about their communities and circumstances as they did, and you do not face the same risks. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott Timeline

Montgomery Bus Boycott Timeline Jan. 1863 Emancipation Proclamation July 1868 Fourteenth Amendment May 1896 Plessy v. Fergusen; 'Separate but Equal' ruled constitutional. May 1909 Niagara Movement convenes (later becomes NAACP), pledging to promote racial equality. 1941 - 1945 U.S. involvement in WWII. 1949 Women’s Political Council in Montgomery, Alabama created. June 1950 - U.S. involvement in the Korean War. July 1953 June 1953 African-Americans in Baton-Rouge, Louisiana boycott segregated city buses. May 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Aug. 1955 Murder of Emmett Till. Dec. 1, 1955 Rosa Parks refuses to give up her seat and is arrested. Dec. 5, 1955 Montgomery Improvement Council formed, Martin Luther King, Jr. named President. Nov. 1956 Supreme Court affirms decision in Browder v. Gayle which found bus segregation unconstitutional. Dec. 1956 Supreme Court rejects city and state appeals on its decision. Buses are desegregated in Montgomery. Montgomery Bus Boycott Document A: Textbook The Montgomery Bus Boycott In 1955, just after the school desegregation decision, a black woman helped change American history. Like most southern cities (and many northern ones), Montgomery had a law that blacks had to sit in the back rows of the bus. One day, Rosa Parks boarded a city bus and sat down in the closest seat. It was one of the first rows of the section where blacks were not supposed to sit. The bus filled up and some white people were standing. The bus driver told Rosa Parks that she would have to give up her seat to a white person. She refused and was arrested.