The Freedom Rides of 1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

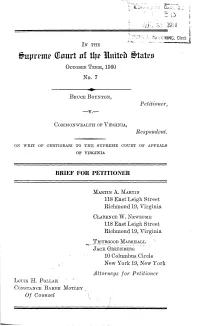

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

REFLECTION REFLECTION the Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights Movement

REFLECTION REFLECTION The Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights Movement “I’m taking a trip on the Greyhound bus line, I’m riding the front seat to New Orleans this time. Hallelujah I’m a travelin’, hallelujah ain’t it fine, Hallelujah I’m a travelin’ down freedom’s main line.” This reflection is based on the PBS documentary, “Freedom Riders,” which is a production of The American Experience. To watch the film, go to: http://to.pbs.org/1VbeNVm. SUMMARY OF THE FILM From May to November 1961, over 400 Americans, both black and white, witnessed the power of nonviolent activism for civil rights. The Freedom Riders were opposing the racist Jim Crow laws of the South by riding bus lines from Washington, D.C., down through the Deep South. These Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Despite the violence, threats, and extraor- dinary racism they faced, people of conscience, both black and white, Northern and Southern, rich and poor, old and young, carried out the Freedom Rides as a testimony to the basic truth all Americans hold: that the government must protect the constitutional rights of its people. Finally, on September 22, 1961, segregation on the bus lines ended. This was arguably the movement that changed the force and effectiveness of the Civil Rights Movement as a whole and set the stage for other organized movements like the Selma to Montgomery March and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This documentary is based on the book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Equality by Raymond Arsenault (http://bit.ly/1Vbn4sy). -

Surprise, Security, and the American Experience Jan Van Tol

Naval War College Review Volume 58 Article 11 Number 4 Autumn 2005 Surprise, Security, and the American Experience Jan van Tol John Lewis Gaddis Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation van Tol, Jan and Gaddis, John Lewis (2005) "Surprise, Security, and the American Experience," Naval War College Review: Vol. 58 : No. 4 , Article 11. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol58/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen van Tol and Gaddis: Surprise, Security, and the American Experience BOOK REVIEWS HOW COMFORTABLE WILL OUR DESCENDENTS BE WITH THE CHOICES WE’VE MADE TODAY? Gaddis, John Lewis. Surprise, Security, and the American Experience. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 2004. 150pp. $18.95 John Lewis Gaddis is the Robert A. U.S. history, American assumptions Lovell Professor of History at Yale Uni- about national security were shattered versity and one of the preeminent his- by surprise attack, and each time U.S. torians of American, particularly Cold grand strategy profoundly changed as a War, security policy. Surprise, Security, result. and the American Experience is based on After the British attack on Washington, a series of lectures given by the author D.C., in 1814, John Quincy Adams as in 2002 addressing the implications for secretary of state articulated three prin- American security after the 11 Septem- ciples to secure the American homeland ber attacks. -

Movement 1954-1968

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 1954-1968 Tuesday, November 27, 12 NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AFFAIRS Curated by Ben Hazard Tuesday, November 27, 12 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, The initial phase of the black protest activity in the post-Brown period began on December 1, 1955. Rosa Parks of Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat to a white bus rider, thereby defying a southern custom that required blacks to give seats toward the front of buses to whites. When she was jailed, a black community boycott of the city's buses began. The boycott lasted more than a year, demonstrating the unity and determination of black residents and inspiring blacks elsewhere. Martin Luther King, Jr., who emerged as the boycott movement's most effective leader, possessed unique conciliatory and oratorical skills. He understood the larger significance of the boycott and quickly realized that the nonviolent tactics used by the Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi could be used by southern blacks. "I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom," he explained. Although Parks and King were members of the NAACP, the Montgomery movement led to the creation in 1957 of a new regional organization, the clergy-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) with King as its president. King remained the major spokesperson for black aspirations, but, as in Montgomery, little-known individuals initiated most subsequent black movements. On February 1, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College began a wave of student sit-ins designed to end segregation at southern lunch counters. -

AFS 2390 Introduction to African-American Literature: Literature and AFS - AFRICAN AMERICAN Writing Cr

AFS 2390 Introduction to African-American Literature: Literature and AFS - AFRICAN AMERICAN Writing Cr. 3 Satisfies General Education Requirement: Diversity Equity Incl Inquiry, STUDIES Intermediate Comp Pre-2018, Intermediate Comp Post-2018 Introduction to major themes and some major writers of African- AFS 1010 Introduction to African American Studies Cr. 3 American literature, emphasizing modern works. Reading and writing Satisfies General Education Requirement: Diversity Equity Incl Inquiry, about representative poetry, fiction, essays, and plays. Offered Every Social Inquiry Term. An interdisciplinary approach to exploring several broad issues, topics, Prerequisites: ENG 1020 with a minimum grade of C, ENG 1020 with a theories, concepts and perspectives which describe and explain the minimum grade of P, ENG 1050 with a minimum grade of C, College Level experiences of persons of African descent in America, the Continent, and Exam Program with a test score minimum of BC-BD, (AA) Exempt from the diaspora. Offered Every Term. Gen Ed MACRAO with a test score minimum of 100, Michigan Transfer AFS 2010 African American Culture: Historical and Aesthetic Roots Cr. 4 Agreement with a test score minimum of 100, or (BA) Competencies Satisfies General Education Requirement: Cultural Inquiry, Civ and Waiver with a test score minimum of 100 Societies (CLAS only), Diversity Equity Incl Inquiry Equivalent: ENG 2390 Examination of the historical, traditional and aesthetic bases of a variety AFS 2600 Race and Racism in America Cr. 3 of cultural forms -- language, literature, music -- of the Black experience. Satisfies General Education Requirement: Diversity Equity Incl Inquiry Offered Every Term. Examination of the nature and practice of racism in American society AFS 2210 Black Social and Political Thought Cr. -

We As Freemen

WE AS FREEMEN WE AS FREEMEN Plessy v. Ferguson By Keith Weldon Medley PELICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Gretna 2003 Copyright © 2003 By Keith Weldon Medley All rights reserved The word “Pelican” and the depiction of a pelican are trademarks of Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., and are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Medley, Keith Weldon. We as freemen : Plessy v. Ferguson and legal segregation / by Keith Weldon Medley. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 1-58980-120-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Plessy, Homer Adolph—Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Segregation in transportation—Law and legislation—Louisiana—History. 3. Segregation—Law and legislation—United States—History. 4. United States—Race relations—History. I. Title: Plessy v. Ferguson. II. Title. KF223.P56 M43 2003 342.73’0873—dc21 2002154505 Printed in the United States of America Published by Pelican Publishing Company, Inc. 1000 Burmaster Street, Gretna, Louisiana 70053 In memory of my parents, Alfred Andrew Medley, Sr., and Veronica Rose Toca Medley For my sons, Keith and Kwesi “We, as freemen, still believe that we were right and our cause is sacred.” —Statement of the Comité des Citoyens, 1896 Contents Acknowledgments 0 Chapter 1 A Negro Named Plessy 000 Chapter 2 John Howard Ferguson 000 Chapter 3 Albion W. Tourgee 000 Chapter 4 One Country, One People 000 Chapter 5 The Separate Car Act of 1890 000 Chapter 6 Who Will Bell the Cat? 000 Chapter 7 Are You a Colored Man? 000 Chapter 8 My Dear Martinet 000 Chapter 9 We as Freemen 000 Chapter 10 The Battle of Freedom 000 Appendix A: Further Reading 000 Notes 000 Index 000 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. -

Nominees and Bios

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Pre‐Emancipation Period 1. Emanuel Driggus, fl. 1645–1685 Northampton Co. Enslaved man who secured his freedom and that of his family members Derived from DVB entry: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Driggus_Emanuel Emanuel Driggus (fl. 1645–1685), an enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and several members of his family exemplified the possibilities and the limitations that free blacks encountered in seventeenth‐century Virginia. His name appears in the records of Northampton County between 1645 and 1685. He might have been the Emanuel mentioned in 1640 as a runaway. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor are the date and circumstances of his arrival in Virginia. His name, possibly a corruption of a Portuguese surname occasionally spelled Rodriggus or Roddriggues, suggests that he was either from Africa (perhaps Angola) or from one of the Caribbean islands served by Portuguese slave traders. His first name was also sometimes spelled Manuell. Driggus's Iberian name and the aptitude that he displayed maneuvering within the Virginia legal system suggest that he grew up in the ebb and flow of people, goods, and cultures around the Atlantic littoral and that he learned to navigate to his own advantage. 2. James Lafayette, ca. 1748–1830 New Kent County Revolutionary War spy emancipated by the House of Delegates Derived from DVB/ EV entry: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lafayette_James_ca_1748‐1830 James Lafayette was a spy during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Born a slave about 1748, he was a body servant for his owner, William Armistead, of New Kent County, in the spring of 1781. -

Biography Bottle Project Due Date: February 3, 2015 Students Will

Biography Bottle Project Due Date: February 3, 2015 Students will learn as they celebrate Black History Month in February, by (1) researching facts {biographies/auto‐biographies/non‐fiction text} to write a 3 paragraph essay, in school, and (2) creating a Biography Bottles Statue/Image, at home, that will be displayed in our school library, during the month of February. It is important that all the deadlines listed below are met so that students do not fall behind and miss the due dates. The subject for the bio‐bottle project will be a famous African American that is selected, from a given list, by students and approved by the teacher on January 15th. The reading/research for this project will be done at home and at school. The reading/research should be completed by Wednesday, January 21st. Please have parents sign and return the slips listed below to teachers by Wednesday, January 21st. The completed Biography Bottle Statue/Image is due on Tuesday, February 3rd . Attached to this document is the grading rubric that I will use to for the bio bottle project. Materials needed for the bottle: 1 plastic bottle . For example: Small water or soda bottle 2 liter soda bottle Ketchup bottle Dish soap bottle o Please note the a minimum size should be at least 16 ounces, and the maximum size should be a 2 liter bottle Sand, dirt, or gravel to put in the bottom of your bottle to anchor it Things to decorate your bottle to look like the person you have researched . For example: Paint, yarn, glue, sequins, felt, beads, feathers, colored paper, pipe cleaners, Styrofoam balls, fabric, buttons, clay, googly eyes, etc. -

Religious Diversity in America an Historical Narrative

Teaching Tool 2018 Religious Diversity in America An Historical Narrative Written by Karen Barkey and Grace Goudiss with scholarship and recommendations from scholars of the Haas Institute Religious Diversity research cluster at UC Berkeley HAASINSTITUTE.BERKELEY.EDU This teaching tool is published by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at UC Berkeley This policy brief is published by About the Authors Citation the Haas Institute for a Fair and Karen Barkey is Professor of Barkey, Karen and Grace Inclusive Society. This brief rep- Sociology and Haas Distinguished Goudiss. “ Religious Diversity resents research from scholars Chair of Religious Diversity at in America: An Historical of the Haas Institute Religious Berkeley, University of California. Narrative" Haas Institute for Diversities research cluster, Karen Barkey has been engaged a Fair and Inclusive Society, which includes the following UC in the comparative and historical University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley faculty: study of empires, with special CA. September 2018. http:// focus on state transformation over haasinstitute.berkeley.edu/ Karen Munir Jiwa time. She is the author of Empire religiousdiversityteachingtool Barkey, Haas Center for of Difference, a comparative study Distinguished Islamic Studies Published: September 2018 Chair Graduate of the flexibility and longevity of Sociology Theological imperial systems; and editor of Union, Berkeley Choreography of Sacred Spaces: Cover Image: A group of people are march- Jerome ing and chanting in a demonstration. Many State, Religion and Conflict Baggett Rossitza of the people are holding signs that read Resolution (with Elazar Barkan), "Power" with "building a city of opportunity Jesuit School of Schroeder that works for all" below. -

100 Facts About Rosa Parks on Her 100Th Birthday

100 Facts About Rosa Parks On Her 100th Birthday By Frank Hagler SHARE Feb. 4, 2013 On February 4 we will celebrate the centennial birthday of Rosa Parks. In honor of her birthday here is a list of 100 facts about her life. 1. Rosa Parks was born on Feb 4, 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. ADVERTISEMENT Do This To Fix Car Scratches This car gadget magically removes scratches and scuffs from your car quickly and easily. trynanosparkle.com 2. She was of African, Cherokee-Creek, and Scots-Irish ancestry. FEATURED VIDEOS Powered by Sen Gillibrand reveals why she's so tough on Al Franken | Mic 2020 NOW PLAYING 10 Sec 3. Her mother, Leona, was a teacher. 4. Her father, James McCauley, was a carpenter. 5. She was a member of the African Methodist Episcopal church. 6. She attended the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery. 7. She attended the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes for secondary education. 8. She completed high school in 1933 at the age of 20. 9. She married Raymond Parker, a barber in 1932. 10. Her husband Raymond joined the NAACP in 1932 and helped to raise funds for the Scottsboro boys. 11. She had no children. 12. She had one brother, Sylvester. 13. It took her three tries to register to vote in Jim Crow Alabama. 14. She began work as a secretary in the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943. 15. In 1944 she briefly worked at Maxwell Air Force Base, her first experience with integrated services. 16. One of her jobs within the NAACP was as an investigator and activist against sexual assaults on black women. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr

Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. “Labor, Racism, and Justice in the 21st Century” The 2015 Jerry Wurf Memorial Lecture The Labor and Worklife Program Harvard Law School JERRY WURF MEMORIAL FUND (1982) Harvard Trade Union Program, Harvard Law School The Jerry Wurf Memorial Fund was established in memory of Jerry Wurf, the late President of the American Federation of State, County and Munic- ipal Employees (AFSCME). Its income is used to initiate programs and activities that “reflect Jerry Wurf’s belief in the dignity of work, and his commitment to improving the quality of lives of working people, to free open thought and debate about public policy issues, to informed political action…and to reflect his interests in the quality of management in public service, especially as it assures the ability of workers to do their jobs with maximum effect and efficiency in environments sensitive to their needs and activities.” Jerry Wurf Memorial Lecture February 19, 2015 Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. “Labor, Racism, and Justice in the 21st Century” Table of Contents Introduction Naomi Walker, 4 Assistant to the President of AFSCME Keynote Address Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. 7 “Labor, Racism, and Justice in the 21st Century” Questions and Answers 29 Naomi Walker, Assistant to the President of AFSCME Hi, good afternoon. Who’s ready for spring? I am glad to see all of you here today. The Jerry Wurf Memorial Fund, which is sponsoring this forum today, was established in honor of Jerry Wurf, who was one of AFSCME’s presidents from 1964 till 1981. These were really incredibly formative years for our union and also nationally for this nation.