Stepping Into Selma: Voting Rights History and Legacy Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H

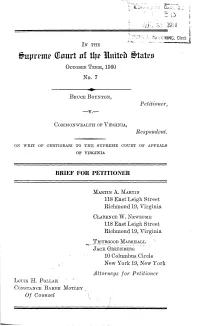

IN THE 71uprrmtr (21nrl of 11ir littitch tatras OCTOBER TERM, 1960 No. 7 BRUCE BOYNTON, Petitioner, -v.--- COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA BRIEF FOR PETITIONER MARTIN A. MARTIN 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia CLARENCE W. NEWSOME 118 East Leigh Street Richmond 19, Virginia THURGOOD MARSHALL JACK GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle New York 19, New York Attorneys for Petitioner LOUIS H. POLLAK CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY Of Counsel r a n TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opinions Below -------....-....-------- ------------------- 1 Jurisdiction ------------------------ ------------- 1 Questions Presented ------------------- ------------ 2 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved -.. 2 Statement --- --- .----------------------- ------------- 3 Summary of Argument ------..---------------------- 5 Argument -----------..--.....--- ----------- 6 Introductory ------------- -------------------- 6 The statute involved -- ---------------------- 6 Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8 I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab- lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti- tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu- larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal ------..------------- 14 II. Petitioner's criminal conviction which served only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restaurant conflicts with principles established by decisions of this Court, and there- by violates the Fourteenth Amendment --------- 22 Conclusion --- .--.--...---- 2626---... ii TABLE OF CASES PAGE Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ------------------- 11 Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 ----------- 15 Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 21 Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 --------------------- 21 Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

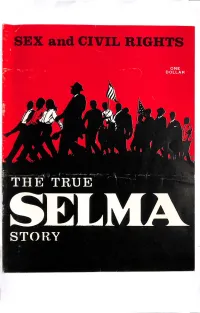

Martin Luther King and Communism Page 20 the Complete Files of a Communist Front Organization Were Taken in a Raid in New Orleans

Several hundred demonstrators were forced to stand on Dexter Ave1me in front of the State Capitol at Montgomery. On the night of March 10, 1965, these demonstrators, who knew that once they left the area they would not be able to return, urinated en masse in the street on the signal of James Forman, SNCC ExecJJtiVe Director. "All right," Forman shoute<)l, "Everyone stand up and relieve yourself." Almost everyone did. Some arrests were made of men who went to obscene extremes in expos ing themselves to local police officers. The True SELMA Story Albert C. (Buck) Persons has lived in Birmingham, Alabama for 15 years. As a stringer for LIFE and managing editor of a metropolitan weekly newspaper he covered the Birmingham demonstrations in 1963. On a special assignment for Con gressman William L. Dickinson of Ala bama he investigated the Selma-Mont gomery demonstrations in March, 1965. In 1961 Persons was one of a handful of pilots hired to support the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. His story on this two years later led to the admission by President Kennedy that four Ameri can flyers had died in combat over the beaches of Southern Cuba in an effort to drive Fidel Castro from the armed Soviet garrison that had been set up 90 miles off the coast of the United States. After interviewing scores of people who were eye-witnesses to the Selma-Montgomery march, Mr. Persons has written the articles published here. In summation he says, "The greatest obstacle in the Negro's search for "freedom" is the Negro himself and the leaders he has chosen to follow. -

John Lewis, Reflections on Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., 109 Yale L.J

+(,121/,1( Citation: John Lewis, Reflections on Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., 109 Yale L.J. 1253, 1256 (2000) Provided by: Available Through: The Jones Day Libraries Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Sep 8 16:33:48 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device Reflections on Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. John Lewist For any student of the law, indeed for any person who believes in the values for which the Constitution of the United States stands, the name Frank Minis Johnson, Jr. should ring familiar. Frank Johnson was the best example of what this country can be. More than simply a model jurist, he was a model American. As debate rages today over the role of the judiciary and whether one should support the appointment of "strict constructionist" or "activist" judges to the bench, Judge Johnson's record stands above the fray. His career demonstrates the wisdom of those great Americans who drafted our Constitution. Our forefathers proved wise enough to provide the courts not only the moral authority-based in our Constitution and Bill of Rights and embodied in people like Judge Johnson-but also the independence necessary to exert that authority at those times when the bedrock of our freedom-the right of all Americans to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness-is threatened. -

Minimum Moral Rights: Alabama Mental Health Institutions

MINIMUM MORAL RIGHTS: ALABAMA MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND THE ROAD TO FEDERAL INTERVENTION Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work describe in this thesis is my own or was one in collaboration with my advisory committee. This thesis does not include proprietary or classified information. ____________________________ Deborah Jane Belcher Certificate of Approval ___________________________ __________________________ Larry Gerber David Carter, Chair Professor Emeritus Associate Professor History History ___________________________ __________________________ Charles Israel George T. Flowers Associate Professor Dean History Graduate School MINIMUM MORAL RIGHTS: ALABAMA MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND THE ROAD TO FEDERAL INTERVENTION Deborah Jane Belcher A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts Auburn, Alabama December 19, 2008 MINIMUM MORAL RIGHTS: ALABAMA MENTAL HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND THE ROAD TO FEDERAL INTERVENTION Deborah Jane Belcher Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights __________________________________ Signature of Author ___________________________________ Date of Graduation iii VITA Deborah Jane Belcher was born in Mt. Clemons, Michigan. A graduate of Marshall Lab School in Huntington, West Virginia, Deborah attended Marshall University where she -

Learning from History the Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan

Building a Culture of Peace Forum Learning From History The Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan Thursday, January 12, 2017 photo: James Garvin Ellis 7 to 9 pm (please arrive by 6:45 pm) Unitarian Universalist Church Free and 274 Pleasant Street, Concord NH 03301 Open to the Public Starting in September, 1959, the Rev. James Lawson began a series of workshops for African American college students and a few allies in Nashville to explore how Gandhian nonviolence could be applied to the struggle against racial segregation. Six months later, when other students in Greensboro, NC began a lunch counter sit-in, the Nashville group was ready. The sit- As the long-time New in movement launched the England Coordinator for Student Nonviolent Coordinating the War Resisters League, and as former Chair of War James Lawson Committee, which then played Photo: Joon Powell Resisters International, crucial roles in campaigns such Joanne Sheehan has decades as the Freedom Rides and Mississippi Freedom Summer. of experience in nonviolence training and education. Among those who attended Lawson nonviolence trainings She is co-author of WRI’s were students who would become significant leaders in the “Handbook for Nonviolent Civil Rights Movement, including Marion Barry, James Bevel, Campaigns.” Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivian. For more information please Fifty-six years later, Joanne Sheehan uses the Nashville contact LR Berger, 603 496 1056 Campaign to help people learn how to develop and participate in strategic nonviolent campaigns which are more The Building a Culture of Peace Forum is sponsored by Pace e than protests, and which call for different roles and diverse Bene/Campaign Nonviolence, contributions. -

Freedom Teachers : Northern White Women Teaching in Southern Black Communities, 1860'S and 1960'S

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2001 Freedom teachers : Northern White women teaching in Southern Black communities, 1860's and 1960's. Judith C. Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Hudson, Judith C., "Freedom teachers : Northern White women teaching in Southern Black communities, 1860's and 1960's." (2001). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5562. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5562 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM TEACHERS: NORTHERN WHITE WOMEN TEACHING IN SOUTHERN BLACK COMMUNITIES, 1860s AND 1960s A Dissertation Presented by JUDITH C. HUDSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2001 Social Justice Education Program © Copyright by Judith C. Hudson 2001 All Rights Reserved FREEDOM TEACHERS: NORTHERN WHITE WOMEN TEACHING IN SOUTHERN BLACK COMMUNITIES, 1860s AND 1960s A Dissertation Presented by JUDITH C. HUDSON Approved as to style and content by: Maurianne Adams, Chair ()pMyu-cAI oyLi Arlene Voski Avakian, Member ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . I would like to acknowledge the financial support of the American Association of University Women. I received a Career Development Grant which allowed me, on a full¬ time basis, to begin my doctoral study of White women’s anti-racism work. -

Wildlife in an Ethiopian Valley by Emil K

342 Oryx Wildlife in an Ethiopian Valley By Emil K. Urban and Leslie H. Brown On several flights and safaris in the lower Omo River valley the authors and others recorded the numbers of larger mammals they saw. The results showed no regular general migration pattern, although certain species showed trends, notably eland, zebra, elephant and Lelwel's hartebeest which moved into the area after the rains and out again when the grass died. Dr Urban is working in the Department of Biology in the Haile Sellassie I University in Addis Ababa. Leslie Brown, well known Kenya naturalist, is a UNESCO wildlife consultant. HERE are large numbers of mammals in the plains and foothills on T either side of the lower Omo River, including game animals, some in large concentrations, that have been reduced or are extinct eleswhere in Ethiopia. These mammals, their seasonal movements and population den- sities have not been documented and are very little known, although it is suspected that their movements in the lower Omo plains are related to more widespread movements in the Sudan. This paper reports scattered observations of larger mammals in the area between January 1965 and June 1967. They are, needless to say, inadequate for a full picture of the migratory game movements. Between us we made five trips: January 1965, LHB and Ian Grimwood; March, EKU; September, EKU; December, EKU and John Blower; and March 1967, LHB. In addition John Blower, Senior Game Warden of the Imperial Ethiopian Government's Wild Life Conservation Depart- ment, visited the area in October 1965 and February 1966, and G. -

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

IN HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 10 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of